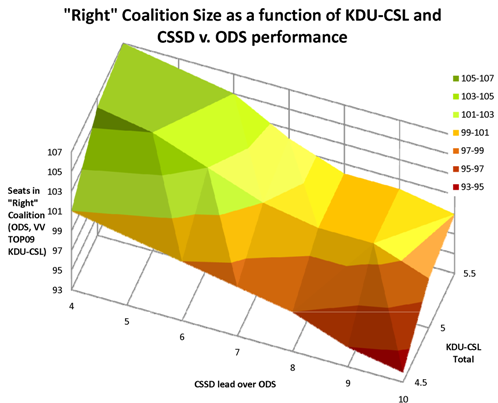

A quick calculation. Even at current levels (which include the absence of MKP-SMK, which is looking increasingly likely), a Smer-SNS coalition would have just barely enough to sustain a majority. If Smer loses even 4 points from its current level (down to 34%) or Smer loses 3% and SDKU gains 1%, then Smer loses its ability to form a government with SNS. The final result may not be as resounding a victory as the exit polls suggested, but it still bodes fairly well for the current opposition (except, maybe, MKP-SMK).

A quick calculation. Even at current levels (which include the absence of MKP-SMK, which is looking increasingly likely), a Smer-SNS coalition would have just barely enough to sustain a majority. If Smer loses even 4 points from its current level (down to 34%) or Smer loses 3% and SDKU gains 1%, then Smer loses its ability to form a government with SNS. The final result may not be as resounding a victory as the exit polls suggested, but it still bodes fairly well for the current opposition (except, maybe, MKP-SMK).

Tag: elections

Slovakia Election Update: End of an era

I have lived my entire professional life with HZDS, frequently visiting its offices, often taking it to task for what I regarded as serious accountability violations. And with this set of results for the SUSR, I think it is gone. (I think it is the first time HZDS has ever fallen below 5% in any official count. I suppose it may come back, but its demographics suggest it won’t). I can’t say that I weep for Slovakia or for Meciar, but it does feel a bit weird to think that this part of Slovakia’s political life–and my own personal life–is now “history” in both senses of the word.l

I have lived my entire professional life with HZDS, frequently visiting its offices, often taking it to task for what I regarded as serious accountability violations. And with this set of results for the SUSR, I think it is gone. (I think it is the first time HZDS has ever fallen below 5% in any official count. I suppose it may come back, but its demographics suggest it won’t). I can’t say that I weep for Slovakia or for Meciar, but it does feel a bit weird to think that this part of Slovakia’s political life–and my own personal life–is now “history” in both senses of the word.l

Slovakia Election Update: First post-election polls suggest big win for the opposition.

The polls are closed and we have poll numbers, delayed a bit by storm-related power outages. There will be a shorter lag than usual between the exit polls and the election results and the isolated nature of the delay may mess up the percentages in the previous post (or not.)

FOCUS did a telephone survey today and MVK appears to have done a traditional in-person exit poll. The results are below.

If these are correct, then the results are a clear victory for the current opposition, and would, indeed, allow a 4 party rather than a 5 party government from the current opposition (though 5 parties would give a much bigger margin of error along with a much bigger set of headaches).

Even if these numbers follow the norm of 2 point average error and the beneficiary is in each case the current coalition, the current coalition would not come near a majority, unless one of the Hungarian parties falls below the threshold (and even then it would be a narrow thing)

Of course these are still polls, however recent they may be. The next step is estimation from the preliminary results. We only have 4% of precincts in at present, and they do give Smer a commanding lead, but this is actually pretty much what we would expect from the way that election results come in in Slovakia and when I extrapolate the lines, they actually correspond fairly closely with the exit polls. Twenty minutes more and we should know.

| FOCUS | Seats | MVK | Seats | |

| Smer | 29.7 | 51 | 28 | 49 |

| SDKU | 18.1 | 31 | 15.8 | 28 |

| SaS | 11.6 | 20 | 12.4 | 22 |

| KDH | 9.1 | 16 | 9.9 | 17 |

| SNS | 6.3 | 10 | 5.7 | 10 |

| HZDS | 4.3 | 0 | 4.7 | 0 |

| MKP-SMK | 6.3 | 11 | 5.7 | 11 |

| Most-Hid | 6.7 | 11 | 8.2 | 14 |

| SDL | 2.9 | 0 | 3.0 | 0 |

| AZEN | ||||

| NS |

Slovakia Election Update: How to read the early results

In a few hours (22:00 CET, 4pm ET) the papers and TV stations will fall all over themselves to present early results based on exit polls (unless they ignored the lesson that STV learned the hard way in 2006: even the most elaborate large-sample pre-election survey is not the same as an exit poll). About an hour later, results will begin to trickle in and then turn into a torrent. Both of these allow just enough data to make a prediction about the final result. Those with any common sense will go to a movie or find something else to do until about 0:30 CET/6:30 PM ET when there may be enough data to make a final call (though in an election as close as this one, that may not be enough time), but there is probably not anybody that sensible still reading this blog. So if you want to make a guess about the final from the exit polls or from the early results, here is what to do:

In a few hours (22:00 CET, 4pm ET) the papers and TV stations will fall all over themselves to present early results based on exit polls (unless they ignored the lesson that STV learned the hard way in 2006: even the most elaborate large-sample pre-election survey is not the same as an exit poll). About an hour later, results will begin to trickle in and then turn into a torrent. Both of these allow just enough data to make a prediction about the final result. Those with any common sense will go to a movie or find something else to do until about 0:30 CET/6:30 PM ET when there may be enough data to make a final call (though in an election as close as this one, that may not be enough time), but there is probably not anybody that sensible still reading this blog. So if you want to make a guess about the final from the exit polls or from the early results, here is what to do:

How to guess from the exit polls:

Don’t, especially for close races (like whether Most-Hid and HZDS are above the threshold). Exit polls are better than other kinds of polls but they are far from perfect. Below you can find two charts with exit poll results and actual results, one for Slovakia in 2006 and one for the Czech Republic just two weeks ago in May 2010. They are remarkably similar in their overall results: the average difference between exit polls and actual results for the eight top parties in each is about 0.7 or 0.8 and as high as 2.0 even for medium-sized parties. This translates into differences up or down of as much as 20%, especially (but not exclusively) for the smaller parties. If we could assume that the 2010 difference would resemble that of 2010, then I think we could make a better prediction from exit polls, but except for SNS (whose voters might not be able to quite admit their choice to a bunch of young exit pollsters), I am not sure how this year’s exit polls will differ from results. Of course if HZDS scores 7.2% or SMK-MKP scores 3% we can be fairly sure of those parties final position vis a vis the exit polls, but I don’t expect this.

| Country | Party | Exit Poll | Results | Exit Poll Raw Error | Exit Poll Percentage Error |

| Slovakia 2006 | Smer | 27.2 | 29.1 | -1.9 | -7% |

| SDKU | 19 | 18.4 | +0.6 | +4% | |

| SNS | 9.6 | 11.7 | -2.1 | -18% | |

| HZDS | 8.6 | 8.8 | -0.2 | -2% | |

| SMK | 11.8 | 11.7 | +0.1 | +1% | |

| KDH | 8.6 | 8.3 | +0.3 | +3% | |

| KSS | 4.7 | 3.9 | +0.8 | +21% | |

| SF | 3.8 | 3.5 | +0.3 | +10% | |

| Average (absolute value) | 0.8 | 8% | |||

| Country | Party | Exit Poll | Results | Exit Poll Raw Error | Exit Poll Percentage Error |

| Czech Republic 2010 | Average (absolute value) | 0.8 | 8% | ||

| CSSD | 19.5 | 22.08 | -2.6 | -12% | |

| ODS | 20 | 20.22 | -0.2 | -1% | |

| TOP09 | 17.5 | 16.7 | +0.8 | +5% | |

| KSCM | 10.5 | 11.27 | -0.8 | -7% | |

| VV | 11 | 10.88 | +0.1 | +1% | |

| KDU | 4.5 | 4.39 | +0.1 | +3% | |

| SZ | 3 | 2.44 | +0.6 | +23% | |

| Suverenita | 3 | 3.67 | -0.7 | -18% | |

| Average (absolute value) | 0.7 | 9% | |||

So take a sip of the exit polls, roll them around your mouth, and spit them back and wait for the full glass.

How to guess from early results

I was surprised not to see this done in 2006 (or in the Czech Republic two weeks ago), but maybe I missed it. It should be possible to use the patterns of voting returns from 2006 to help make predictions from early results. In my 2006 live-blogging of the election I actually took snapshots of the results as they came back over time, and I hope to use these tonight to make a better guess. Because the speed of election returns has to do with the size and rurality of precincts, some parties early returns were higher or lower than the final by a significant amount, as the graph from 2006 shows:

Parties with more rural electorates–KDH in light blue, HZDS in brown–tended to decline as the larger urban precincts began to report later in the process (Smer declined as well, though its urban-rural share was about average). More urban parties–SDKU and SF in particular–tended to increase. SNS and MKP-SMK, with concentrations in middle-sized towns did not change much (though this year things will be different at least for MKP-SMK which has lost much of its urban electorate to Most-Hid and should more closely resemble KDH and HZDS, with a declining trendline).

Because parties characteristics with regard to such factors changes quite slowly, this should actually provide a fairly stable source of data that would allow us to use the 2006 data to adjust the 2010 early returns (though I will also be testing the trends from 2010 against those of 2006 as they happen to see if they truly are consistent.) In any case, if 2006 serves as a good guide, here is a matrix to calculate the “actual result.” Search for party and the number of precincts returned at any given time and multiply the result of your party by the percentage listed.

| Party | Adjustment factor: Multiply party score by percentage below to get better predictions of actual results | ||||||

| Number of precincts reporting | |||||||

| 1000 | 2000 | 3000 | 4000 | 5000 | 5800 | 5900 | |

| Smer | 92% | 95% | 96% | 97% | 98% | 100% | 100% |

| SDKU | 123% | 109% | 105% | 105% | 104% | 101% | 100% |

| SNS | 100% | 100% | 100% | 101% | 101% | 100% | 100% |

| MKP | 109% | 109% | 108% | 100% | 96% | 99% | 100% |

| HZDS | 92% | 99% | 101% | 101% | 102% | 101% | 100% |

| KDH | 94% | 96% | 96% | 98% | 101% | 100% | 100% |

| KSS | 89% | 94% | 97% | 98% | 99% | 100% | 100% |

| SF | 118% | 105% | 102% | 103% | 102% | 100% | 100% |

I will try to do this on the blog, but feel free to try it at home. It would not surprise me if the Slovak press has something like this in store (though I have occasionally criticized them for their use of polls, Slovakia’s journalists have been fairly good at adopting new methods if they will give them a leg up on the competition.

I make no promises for this model any more than for the exit poll adjustment, but those who have not done the sensible thing and simply ignored the whole thing until final results are in will probably appreciate the entertainment value.

Czech Election Update: The Election in Pictures

No major news that I want to blog about today–or more precisely nothing that I have time to address–but I wanted to post two pictures from Prague sent to me by friend and Fulbright colleague Andrew Yurkovsky. The first is technically not an election photo–he took it during the World Hockey Championship final–but it captures something very important. The second captures someone very important.

Czech Election Update: Link Roundup

Traveling again today so just a quick post to highlight the best blog posts I’ve seen on the Czech elections. We have clearly entered an area where committed and educated amateurs can and will, for free, produce analysis of equal or better quality than what once would have cost lots of money, either to the consumer or to the newspaper/magazine that paid them. (Yochai Benkler has some excellent analysis on the economics of social production and sharing.)

Traveling again today so just a quick post to highlight the best blog posts I’ve seen on the Czech elections. We have clearly entered an area where committed and educated amateurs can and will, for free, produce analysis of equal or better quality than what once would have cost lots of money, either to the consumer or to the newspaper/magazine that paid them. (Yochai Benkler has some excellent analysis on the economics of social production and sharing.)

- Andrew Roberts on “The 2010 Czech Elections” in The Monkey Cage

- Sean Hanley on “What the Elections Mean” and the composition of the Czech Parliament

- RiskandForecast.com on “Major Lessons of the Czech Election”

There are a few other articles in Czech that deal nicely with key questions:

- What polling firms will do to keep from making such huge errors next time

- The difference (or lack thereof) between old “dinosaurs” and new

These say it better than I could, so for once I’ll let somebody else’s words suffice.

Guest Blogger: Tim Haughton on Slovak Electoral Politics, Part I

![]() More from wide-ranging Tim Haughton, who this time sacrificed dry feet to bring a full report of Tuesday’s political campaigning in Slovakia and showed his political acumen and intrepidity by going not to Bratislava, where everybody goes, but rather to Kosice.

More from wide-ranging Tim Haughton, who this time sacrificed dry feet to bring a full report of Tuesday’s political campaigning in Slovakia and showed his political acumen and intrepidity by going not to Bratislava, where everybody goes, but rather to Kosice.

How to Win Votes and Influence People – Some Reflections from Slovakia

Tim Haughton, University of Birmingham

It’s a question which excites and perplexes scholars and practioners alike: what kind of campaigning really works? How best can a political party spend its time and money to attract and hang on to the support of voters?

With the Czech vote behind us, I decide to head to the other half of the federation, where as all readers of this blog know, the Slovaks are gearing up for their elections. Opening the curtains of the sleeper carriage as the train pulls into Kosice station, I am greeted by the beaming smile of Vladimir Meciar, the three-time prime minister of Slovakia. His billboard promises ‘hovorit Pravdu, dat Pracu a urobit Poriadok’ [speak the truth, create jobs and ensure order].

The three Ps are capitalized, reminding me of Public Private Partnerships. Critics of Meciar’s time as prime minister (and indeed his party’s participation in the current government) might suggest that such PPP arrangements are about taking from the state to give to those near and dear to his party. A lucrative and successful partnership for some, but not for the coffers of the Slovak state. As readers of this blog know, Meciar’s People’s Party-Movement for a Democratic Slovakia (LS-HZDS), once Slovakia’s most successful electoral machine is in danger of falling below the 5% threshold. Perhaps to counter the widespread view that the party is a group of silver and grey-haired Meciar devotees, another poster at Kosice station depicts a large group of smiling twentysomethings, declaring that ‘And the young vote LS-HZDS’. Somehow I’m not convinced we will see a rush of first time voters racing to the polling stations to cast their votes for Meciar. The major challenge for Meciar’s party is to convince voters that it makes sense to support the party on 12 June. The party may still have brand recognition and one of the iconic figures in Slovak politics, but it looks and feels like a party well beyond its shelf-life which seems to have lost its raison d’etre.

The area around the station is full of billboards. Amongst those of the centre-right Slovak Democratic and Christian Union – Democratic Party (SDKU-DS) and the Christian Democratic Movement (KDH) are several of the Slovak National Party (SNS). SNS’s pitch to voters is to pluck at xenophobic and nationalist heart strings. Whilst one of the billboards declares the party’s desire to ensure ‘that our borders remain our borders’ (a clear criticism of the big neighbour to the south), another wants to ensure ‘we don’t feed those who don’t want to work’ underneath a picture of a large, heavily tattooed Roma. Given Presov’s large Roma minority, this is a poster which sadly might be quite effective.

The area around the station is full of billboards. Amongst those of the centre-right Slovak Democratic and Christian Union – Democratic Party (SDKU-DS) and the Christian Democratic Movement (KDH) are several of the Slovak National Party (SNS). SNS’s pitch to voters is to pluck at xenophobic and nationalist heart strings. Whilst one of the billboards declares the party’s desire to ensure ‘that our borders remain our borders’ (a clear criticism of the big neighbour to the south), another wants to ensure ‘we don’t feed those who don’t want to work’ underneath a picture of a large, heavily tattooed Roma. Given Presov’s large Roma minority, this is a poster which sadly might be quite effective.

On arriving at the station I endulge in my usual ritual of buying a range of different newspapers. The leading Slovak paper, Sme, is running a story on the recent TV clash between Prime Minister Robert Fico and the head of the SDKU-DS electoral list, Iveta Radicova. It doesn’t make happy reading for the latter (the majority thought Fico had won), but I wonder how much influence these duels really have. Having watched both British and Czech ‘prime ministerial debates’ in recent weeks, I’m reminded that they can generate plenty of press coverage, can seem to have changed the political landscape, but ultimately – in the British case in particular – may have had little impact. In the Czech case if they had any impact it may have been to persuade some undecided voters not to vote for either Necas or Paroubek.

On arriving at the station I endulge in my usual ritual of buying a range of different newspapers. The leading Slovak paper, Sme, is running a story on the recent TV clash between Prime Minister Robert Fico and the head of the SDKU-DS electoral list, Iveta Radicova. It doesn’t make happy reading for the latter (the majority thought Fico had won), but I wonder how much influence these duels really have. Having watched both British and Czech ‘prime ministerial debates’ in recent weeks, I’m reminded that they can generate plenty of press coverage, can seem to have changed the political landscape, but ultimately – in the British case in particular – may have had little impact. In the Czech case if they had any impact it may have been to persuade some undecided voters not to vote for either Necas or Paroubek.

Elsewhere the papers are full of comments reflecting on the impact of the Czech results on the Slovak elections, most of which miss the key factors. For my money, three points are worth stressing. Firstly, electoral thresholds matter and can consign an evergreen (no not the greens, but KDU-CSL) to life outside parliament. The fact that nothing is sacred and that even long-standing parties with seemingly loyal support bases can fail, is a lesson some Slovak parties will need to take on board. Secondly, CSSD’s disappointing result and Paroubek’s departure must have had a sobering effect on Fico. The combative party leader was Fico’s closest international partner who enthusiastically backed Fico in the 2006 election. He has been more than just a political ally as Fico’s attendance at Paroubek’s wedding (in the role of a witness if memory serves correctly) highlights. Thirdly, it has given a filip to the centre-right. ‘If it possible for the assorted forces of the right to defeat what they like to label “lefist populism” in the Czech Republic, then why not here’ , they proclaim?

After checking into my Kosice hotel I head back to the station to take the train to Presov. After having bought my ticket to Presov and a ticket for the sleeper back to Prague, I notice on the back of the ticket to Presov an SNS advert replete with a picture of the old-new party leader Jan Slota and his one-time successor and now predecessor as party leader Anna Belousovova. Moreover, on the back of the ticket sleeve for my ticket and sleeper reservation is an advert for Bela Bugar’s Most-HID party. These both strike me as clever strategies on the part of the parties. Unlike other campaigning materials voters are given, a train ticket is not heading straight for the rubbish bin and perhaps will be looked at more than one during the journey. Smer-SD activists have also been at work. The slow train from Kosice to Presov may not be a glamourous place to campaign, but a party supporter has clearly been hard at work and has left campaign literature material on each of the little tables next to the windows.

The desire to visit Presov is dictated not by a desire to leave Kosice, but to attend an SDKU-DS political meeting where all the party’s stars and wannbe bigwigs are scheduled to attend. Thanks to the inclement weather the outdoor meeting doesn’t begin as planned at 16:00, nonetheless, campaigning doesn’t stop. Decked out in blue waterproofs young activists distribute party material and in a clever touch reminding Slovaks that their team will play in the World Cup starting in a few days time, they give out a red card like the one used by football referees reminding voters to give Fico a ‘red card’ at the election. It is also fascinating to observe how the different politicians behave. Many of the less well-known politicians use the opportunity to circulate and give the waiting crowd their own electoral material. Thanks to the open lists, the possibility of preference voting means that it is important for these candidates not just to encourage citizens to vote for the party, but they need to plug themselves as well, especially if they are well down on the party list. Whatever the merits of such big rallies for the parties as a whole, they are valuable opportunities for wannabe parliamentarians.

The desire to visit Presov is dictated not by a desire to leave Kosice, but to attend an SDKU-DS political meeting where all the party’s stars and wannbe bigwigs are scheduled to attend. Thanks to the inclement weather the outdoor meeting doesn’t begin as planned at 16:00, nonetheless, campaigning doesn’t stop. Decked out in blue waterproofs young activists distribute party material and in a clever touch reminding Slovaks that their team will play in the World Cup starting in a few days time, they give out a red card like the one used by football referees reminding voters to give Fico a ‘red card’ at the election. It is also fascinating to observe how the different politicians behave. Many of the less well-known politicians use the opportunity to circulate and give the waiting crowd their own electoral material. Thanks to the open lists, the possibility of preference voting means that it is important for these candidates not just to encourage citizens to vote for the party, but they need to plug themselves as well, especially if they are well down on the party list. Whatever the merits of such big rallies for the parties as a whole, they are valuable opportunities for wannabe parliamentarians.

Once the meeting starts it follows a clear script designed to build-up to a climax, blending music and speeches. The best speech of the night is given by former PM Mikulas Dzurinda. If a party funding scandal hadn’t forced him to step down as leader of the party list, he would be the most likely alternative to Fico as PM. Dzurinda delivers his five minute speech with gusto, reminding the audience of his governments’ successes, berating Fico for his mistakes, pointing to the success of the centre-right in the Czech Republic and imploring the good citizens of Presov to get out and vote on 12 June.

Tony Blair’s press guru Alistair Campbell and the spinmeister supreme Peter Mandelson were always keen on making sure all the details are correct, acutely aware of the importance of image and symbols. The SDKU-DS leadership, however, have clearly not studied the New Labour handbook. Indeed, I’m surprised by the little slip-ups in SDKU-DS’s otherwise well-presented (and apart from the late start) slick rally. Two of the slips are made by the two bands providing the music. One plays the riff from Bowie and Queen’s ‘Under pressure’ as they warm up. Well, maybe only I noticed that, but during the performance one band plays Bryan Adams’ ‘the summer of 69’. I’m not sure how many of the audience were paying that much attention, but surely a song which describes 1969 as the ‘best days of my life’ isn’t really an appropriate one in the former Czechslovakia. It might have been the ‘best days of my life’ if one’s name was Gustav Husak, but post-68 Czechoslovakia under normalization wasn’t for most Slovaks.

The other attention to detail seemingly missed by the organizers was the exact location of the stand. Whilst it is opposite one of the busiest bus stops in the city and a Tesco supermarket, it is right in front of the town’s main theatre where they are showing a performance of ‘Marie Antoinette’. As I see former finance minister Ivan Miklos and social affairs minister Ludovit Kanik (who introduced the tough neo-liberal welfare reforms during the last SDKU-DS-led government) standing next to the stage all I can think of is the former French Queen’s infamous line to the masses of Paris ‘Let them eat cake’. Perhaps I am reading to much into these observations, but anyone with a good camera and video recorder could at least use the images to poke some fun at SDKU-DS.

By the time Iveta Radicova speaks it is already over two and a half hours since the event was supposed to start and the rain has been almost unceasing. The water has seeped through the fabric of my shoes and has made my feet all wet. After a few words from the woman who could be prime minister in a few weeks time, all of the party candidates assemble on stage for the grand finale> a rousing rendition of the campaign song ‘Modra je dobra’ (‘Blue is Good’). It’s a great song, originally recorded by the Czech band ‘Zluty pes’, but after so long standing in the rain with soaking socks all I think about is that maybe ‘Modra je dobra, ale mokra nie je’.

By the time Iveta Radicova speaks it is already over two and a half hours since the event was supposed to start and the rain has been almost unceasing. The water has seeped through the fabric of my shoes and has made my feet all wet. After a few words from the woman who could be prime minister in a few weeks time, all of the party candidates assemble on stage for the grand finale> a rousing rendition of the campaign song ‘Modra je dobra’ (‘Blue is Good’). It’s a great song, originally recorded by the Czech band ‘Zluty pes’, but after so long standing in the rain with soaking socks all I think about is that maybe ‘Modra je dobra, ale mokra nie je’.

Czech Election Update: The (Slightly) Bigger Picture

Another quick and ugly post from vacation (thanks to my family for tolerating my obsession even as we drive from city to city to visit loved ones). I wanted briefly to put the 2010 Czech election into the context of the Czech party system over time (the next quick and ugly will, I hope, put it into broader regional perspective, if Josh Tucker of the Monkey Cage doesn’t do it first.

For now, all I wanted to do was to post a few pictures about what the most recent elections say in raw quantitative terms about the Czech party system circa 2010.

The big news is that thanks to this election cycle the Czech Republic’s party system looks significantly different today than it did ten years ago (indeed it is closer to 1992 or 1996) and signs are that the current changes will presage more change (or, to put it in a different and more awkward way, a period of stable change as opposed to stable stability)

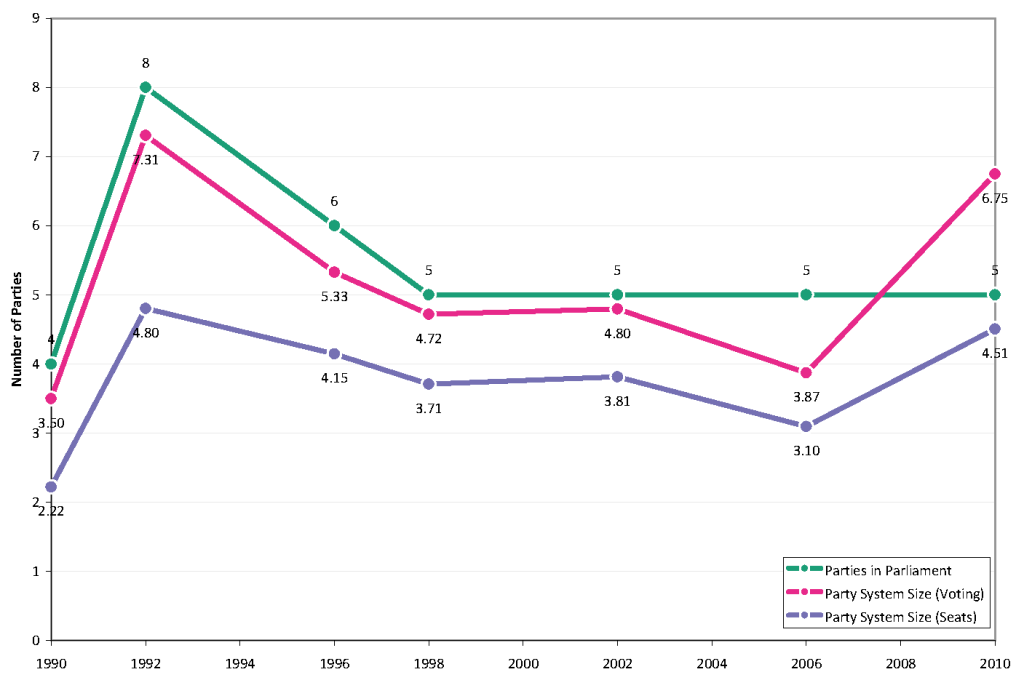

Let’s start with the number of parties:

While the actual number of parties in parliament (the green line) did not change from last election to this one other measures suggest a substantially increased number of parties. The red and blue lines show calculations of party system size based on Taagipera and Laakso’s method which show more significant parties in the voting than any time since 1992 and more even distribution of seats in parliament since 1992 as well (and it actually comes quite close to reaching 1992 levels.

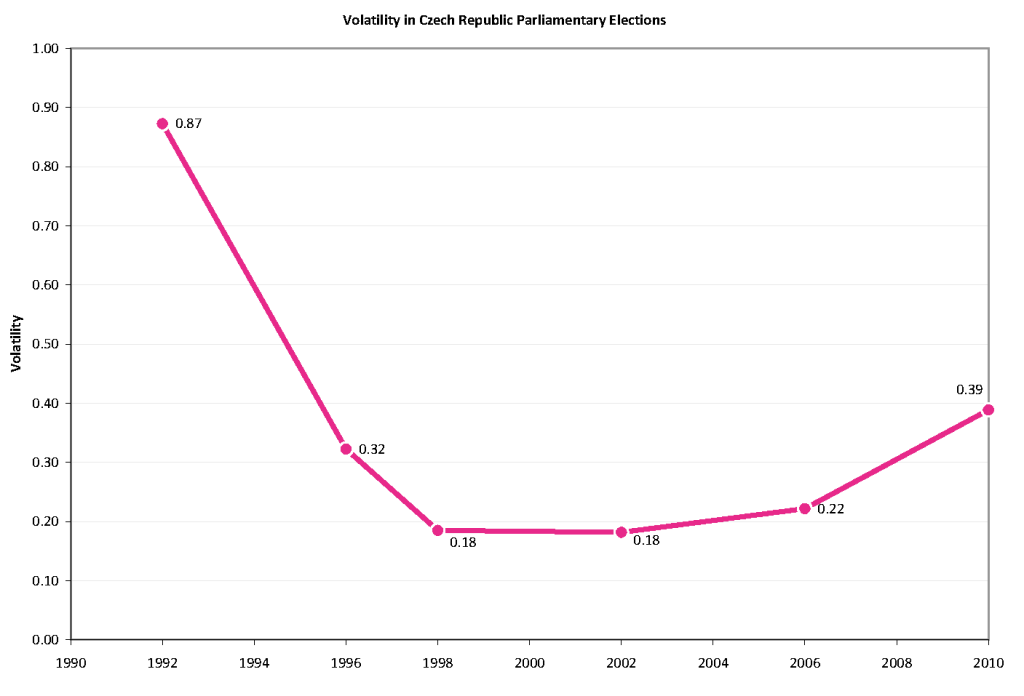

The second major difference is in volatility–the number of seats changing hands from one election to the next. This is actually quite a complicated question because it depends on how we consider succession from one party to the next, but in this election in the Czech Republic the lines of succession are fairly clear (not so in previous elections). Without going into too much detail, volatility in Czech elections looks like this:

While not approaching 1990-1992 levels (and there is a good argument that even 1990-1992 was not that high), this is the highest volatility the Czech Republic has seen since, with only 61% of seats remaining in the hands of parties that held them before the election. (As I will try to discuss tomorrow, while this is unusual for the Czech Republic it actually brings it more within the “normal” range for Central and Eastern Europe.)

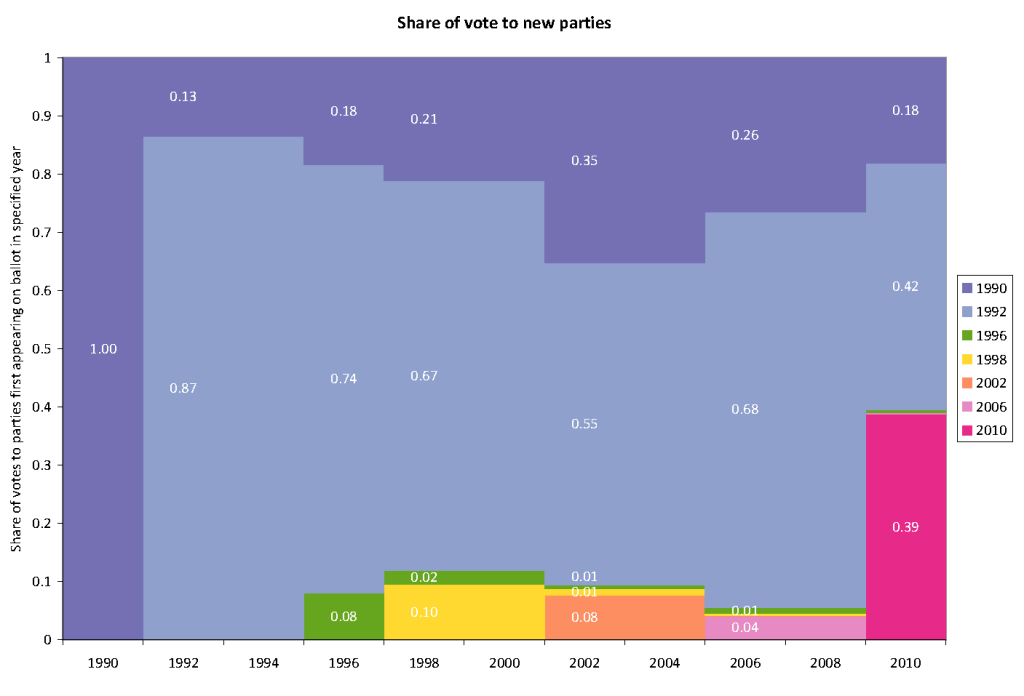

This shift is even more interesting because of the nature of the volatility. Both Tucker and Powell and Mainwaring et al have done fantastic work in the past two years distinguishing between types of volatility and suggesting that it makes a difference if the shift is between parties already in parliament or between parties in parliament and new parties. I do not have time to recreate the calculations of the authors above, but there is another method for displaying it that is perhaps even more provocative. The graph below shows the share of vote going to parties depending on when they first appeared on the ballot (more or less corresponding to when they were created):

What this graph says to me is two things:

- Until this election, nearly all of the Czech vote went to parties that were created in the first two years after the fall of communism.

- New parties appeared, but they almost never survived. It is remarkable that even though dozens of new parties appeared in the Czech Republic between 1992 and 2006, the combined vote totals for those parties in 2010 was less than 1%. The Czech Republic’s political scene today contains parties that are (by Czech standards of 20 years of democracy) rather old (60%) or entirely new (39%) and almost none in between.

- Given that, pattern, the question is what the Czech Republic looks like in 5 or 10 years. If the current new parties show the same survival patterns as their “new” predecessors, they will not exist in one or two election cycles (this is the pattern elsewhere in the region). The old parties may recover some of their voters but probably not all of them and the rest will go on to other new parties which will be equally short lived. The larger this space gets, the larger space it may create for the next election and the more likely the Czech Republic is to find itself with the same patterns as the Baltics and other countries in the region. The Czech party system dog has stopped not barking.

Guest Blogger: Tim Haughton on Czech Electoral Politics

The smiling gentleman pictured here–Tim Haughton of the University of Birmingham–is not a blogger, but he should be, and so I have pressured him into sharing his impressions of electoral politics in the Czech Republic in the run-up to today’s election. I have the good fortune not only to profit from Tim’s insightful analysis of European politics on an almost daily basis but also to be able to call him a close friend. With less than an hour to go before we get the results, I want to share his first-hand observations of the Czech political scene in Prague on the ground level on the last day of campaigning, a piece that is not only astute but also beautifully evocative of the city from which he is writing.

The smiling gentleman pictured here–Tim Haughton of the University of Birmingham–is not a blogger, but he should be, and so I have pressured him into sharing his impressions of electoral politics in the Czech Republic in the run-up to today’s election. I have the good fortune not only to profit from Tim’s insightful analysis of European politics on an almost daily basis but also to be able to call him a close friend. With less than an hour to go before we get the results, I want to share his first-hand observations of the Czech political scene in Prague on the ground level on the last day of campaigning, a piece that is not only astute but also beautifully evocative of the city from which he is writing.

City of Angels: Impressions of the Czech Election Campaign

Tim Haughton, University of Birmingham

There are two rules for political scientists studying an election in another country: don’t just visit the capital and try not to rely on your closest contacts. Although I’ve fallen into both traps, in response to Kevin’s request for a post for his excellent pozorblog, here are a few impressions.

Thanks to the timing of my students’ exams, piles of undergraduate dissertations to mark and other exciting administrative tasks, I arrived in the Czech Republic late on Wednesday with just one day of campaigning to go. As my wife is a native of Prague the first duty (and pleasure) whenever we visit the Czech Republic is to meet up with the family. In a local watering-hole in the shadow of the Staropramen brewery, with the golden beer quenching our thirst, the debate begins.

Thanks to the timing of my students’ exams, piles of undergraduate dissertations to mark and other exciting administrative tasks, I arrived in the Czech Republic late on Wednesday with just one day of campaigning to go. As my wife is a native of Prague the first duty (and pleasure) whenever we visit the Czech Republic is to meet up with the family. In a local watering-hole in the shadow of the Staropramen brewery, with the golden beer quenching our thirst, the debate begins.

My wife’s family all enthusiastically jangled their keys in November 1989 welcoming the end of communist rule. They swung behind Klaus and the Civic Democratic Party (ODS) in the early 1990s keen to see rapid marketization, democratization and a ‘return to Europe’, but as the decade progresses they became increasingly disenchanted by Klaus’s arrogance and the corruption, lies and incompetence of ODS, not just at the national level, but also in the capital where the party has (mis)ruled since the early 1990s. Twenty years after the first time they cast their votes in a free election, they remain largely undecided about whom to vote for this time.

One member of the family is set on voting for the Greens. The party entered parliament in 2006 and became a member of the Topolanek government, but has haemorraged support in the past couple of years and if the polls are to be believed will fall well below the 5% threshold. The support of former president and iconic figure Vaclav Havel maybe doesn’t count for much in Czech politics anymore, but he does offer a sign of where some of the moral, upstanding people may remain in Czech politics.

Another member of the family is inclined to support TOP ’09, a relatively new party formed as the name suggests last year. The centre-right party which offers tradition (‘T’), responsibility (‘O’) and prosperity (‘P’) has at its head Karel Schwarzenberg. The former Foreign Minister (nominated by the Greens to the Topolanek government) is a popular figure who appears everywhere in the TOP 09 material. ‘I am voting for the prince’ declares the family member rather than mentioning the name of the party. The avuncular aristocrat may speak an odd version of Czech betraying his roots and long exile in Austria during communist rule, but he is trusted, not just thanks to his experience and skills, but because he is not afflicted by the disease of Czech politics: corruption.

‘How can you vote for TOP ’09 declares another member of the family? Schwarzenberg maybe a great figures, but ‘what about [Miroslav] Kalousek’. The creator of the new party who shrewdly persuaded Schwarzenberg to join may have been a relatively successful finance minister, but his career is not free from the strains of corruption and dirty dealing. Kalousek – just like leading figures in ODS such as Prague major Pavel Bem and former Prime Minister Mirek Topolanek – is far from being an angel.

All member of the family dislike the Communists with a vengeance and have little sympathy for Jiri Paroubek the leader of the most popular party in the Czech Republic, the Social Democrats (CSSD). Paroubek may have given a very positive impression in CSSD’s party political broadcast as he spoke in glowing terms about his country and vision for the future but put him in a media studio and out comes the street fighter. In the car from the airport my mother-in-law recounts in great detail the insults Paroubek and ODS leader Petr Necas traded during the latest radio debate.

One other round the table is tempted to go for Christian Democratic People’s Party (KDU-CSL). The party lost many prominent members and support when Kalousek left the party to form TOP ’09. The party’s old-new leader Cyril Svoboda is one of the great survivors of Czech politics who has held office in governments led by the left and the right and has not been stained by a major corruption scandal. His moderate, Christian, pro-European stance isn’t everyone’s cup of tea, but even those enthused to vote KDU-CSL recognize the possibility that the party won’t cross the threshold and will hence be a wasted vote.

Where else to head this morning in the city of such whiter than white politicians than ‘Andel’ (angel)? In fact I spent most of the day travelling between Andel and Republic Square. ODS is the dominant party in Prague with strong levels of support. The party offers the best pre-election meeting at least for the hungry and thirsty. The smell of sausages and draught beer entices many of the shoppers to stop and listen to the music and collect the party’s material. Elsewhere on the street young, pretty Czech girls decked out in blue T-shirts (the party’s colour) hand out bags of party material to all who come within range.

Where else to head this morning in the city of such whiter than white politicians than ‘Andel’ (angel)? In fact I spent most of the day travelling between Andel and Republic Square. ODS is the dominant party in Prague with strong levels of support. The party offers the best pre-election meeting at least for the hungry and thirsty. The smell of sausages and draught beer entices many of the shoppers to stop and listen to the music and collect the party’s material. Elsewhere on the street young, pretty Czech girls decked out in blue T-shirts (the party’s colour) hand out bags of party material to all who come within range.

Just along the road is a small CSSD stall. It doesn’t compete in size with the ODS, but it does offer a fuller bag of goodies including a book written by the party’s Prague bigwig, Peter Hulinsky, and has the clever idea of handing out orange roses – a smart way to get the romantic vote. Even if orange is a slightly odd colour for roses (unlike the party’s sister parties abroad CSSD adopted the colour orange thanks to the advice of marketing gurus in the run-up to the 2006 elections), at least orange looks like an almost natural colour for roses, whereas blue would look decidedly odd.

Further along the street are a couple of Green party activists desperately trying to attract the attention of the passing shoppers. Their efforts, even under a sign declaring the greens are not dead, seem not enough to revive the voters who backed the party in 2006. A stall of the small Party of Free Citizens set-up by the Klausite policy wonk Petr Mach has a greater number of party activists sheltering from the drizzle, but it is not attracting much interest, unsurprising for a party which barely registers in opinion polls.

A short metro journey away the Prague Communists are having their final rally. A small crowd of mostly white and grey-haired citizens have congregated to listen to some of the city’s communists including the leader of the party’s list in Prague Jiri Dolejs. No-one seems especially enthusiastic, although one of the female speakers who bemoans developments in the past twenty years earns plenty of nodding heads. The criticisms of developments of the past two decades seem rather incongruent given the party’s stall is next to one of the new shopping centres. A symbol of capitalism sure, but one the citizens of Prague seem to be enjoying with relish judging by the number of shopping bags in hands. On the opposite side of the square, the Social Democrats also have a stall. No set-pieces speeches here, just more orange roses, a jazz quartet and the presence of the larger-than-life Interior Minister Martin Pecina who towers above the citizens who are asking him questions.

A short metro journey away the Prague Communists are having their final rally. A small crowd of mostly white and grey-haired citizens have congregated to listen to some of the city’s communists including the leader of the party’s list in Prague Jiri Dolejs. No-one seems especially enthusiastic, although one of the female speakers who bemoans developments in the past twenty years earns plenty of nodding heads. The criticisms of developments of the past two decades seem rather incongruent given the party’s stall is next to one of the new shopping centres. A symbol of capitalism sure, but one the citizens of Prague seem to be enjoying with relish judging by the number of shopping bags in hands. On the opposite side of the square, the Social Democrats also have a stall. No set-pieces speeches here, just more orange roses, a jazz quartet and the presence of the larger-than-life Interior Minister Martin Pecina who towers above the citizens who are asking him questions.

The surprise package of Czech politics in recent months has been the new party Veci Verejene (‘Public Affairs’). No day of campaigning would be complete without seeing something of the party led by Radek John, which if polls are to be believed, could win around tenth of the votes. The party has a stall opposite its Prague HQ. Under a billboard calling for the end of the dinosaurs in politics, but reminiscent of ODS’s event near Angel, VV has arranged young pretty girls to distribute cakes and chocolates to entice the passing citizens, and for some musicians to persuade those who congregate to tap their feet. Moreover, they have a candy floss (cotton candy) machine.

The surprise package of Czech politics in recent months has been the new party Veci Verejene (‘Public Affairs’). No day of campaigning would be complete without seeing something of the party led by Radek John, which if polls are to be believed, could win around tenth of the votes. The party has a stall opposite its Prague HQ. Under a billboard calling for the end of the dinosaurs in politics, but reminiscent of ODS’s event near Angel, VV has arranged young pretty girls to distribute cakes and chocolates to entice the passing citizens, and for some musicians to persuade those who congregate to tap their feet. Moreover, they have a candy floss (cotton candy) machine.

After lingering for awhile I decide to leave and start walking back to Andel to take the tram back to the in-laws. A few hundred metres from the VV stall a German family with three young children are walking in the same direction as me. They probably know little about Czech political dinosaurs or Radek John, but they are really enjoying the taste of the candy floss. Not everything in Czech politics has such a bitter taste, but the tastiest things are sometimes the offerings of the new to the ignorant.

After lingering for awhile I decide to leave and start walking back to Andel to take the tram back to the in-laws. A few hundred metres from the VV stall a German family with three young children are walking in the same direction as me. They probably know little about Czech political dinosaurs or Radek John, but they are really enjoying the taste of the candy floss. Not everything in Czech politics has such a bitter taste, but the tastiest things are sometimes the offerings of the new to the ignorant.

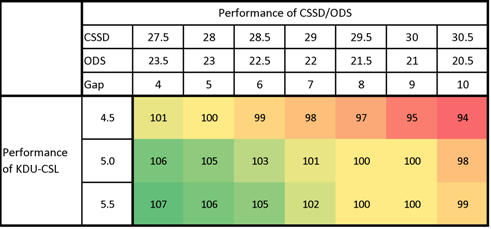

Czech Dashboard News: Final Factum Poll and Coalition Math

Only three days to go and we have now the final allowed-by-law pre-election poll numbers in (the big three of CVVM, STEM and Factum-Invenio; SANEP and Median did not report, but this is probably all right since I am not yet certain how to think about SANEP and I am certain that Median has significant problems). And the result is….

Only three days to go and we have now the final allowed-by-law pre-election poll numbers in (the big three of CVVM, STEM and Factum-Invenio; SANEP and Median did not report, but this is probably all right since I am not yet certain how to think about SANEP and I am certain that Median has significant problems). And the result is….

Well the average of the big three is CSSD 29, ODS 21, Communists at 13, TOP09 and VV at 11 and KDU-CSL just under 5%. But Factum’s poll puts CSSD at 26, ODS at 23 and KDU-CSL just over 5%. As I’ll discuss in a moment, this makes a big difference. But first a schadenfreude interlude.

I have been reporting for a very long time about the insufficiencies of Slovakia’s reporting on public opinion polls, particularly the tendency to treat each new poll as an utterly independent news item without any regard for previous polls by the same firm or contemporary polls by other firms. As somebody who has frequently championed equality of status between Slovakia and the Czech Republic, I am happy to report the otherwise sad news that Czech reporters are just as limited as their Slovak counterparts. Dnes reports “Left has lost its majority, ODS strengthened” but ODS improved by a mere 1.2% (well within any margin of error for such a poll, though of course the story did not mention any margin of error) and by my estimation of seats, the left has not had a majority in the Factum poll since February, so it’s only in comparison to other polls that the left lost ground. But of course that’s not the right comparison to make. To be fair a better Dnes article published twelve hours later interviews the directors of the three major firms and uses their responses to compare the major polls, how they ask questions and why they differ. It also does a good job of looking at the consequences of the elections. But this is not an excuse, I think, for bad reporting of the results on the fly. It does not take a conversation with Kunstat, Hartl and Herzmann to have a sense of why polls differ or why an article should not report on more recent polls as if they are more accurate polls.

I have been reporting for a very long time about the insufficiencies of Slovakia’s reporting on public opinion polls, particularly the tendency to treat each new poll as an utterly independent news item without any regard for previous polls by the same firm or contemporary polls by other firms. As somebody who has frequently championed equality of status between Slovakia and the Czech Republic, I am happy to report the otherwise sad news that Czech reporters are just as limited as their Slovak counterparts. Dnes reports “Left has lost its majority, ODS strengthened” but ODS improved by a mere 1.2% (well within any margin of error for such a poll, though of course the story did not mention any margin of error) and by my estimation of seats, the left has not had a majority in the Factum poll since February, so it’s only in comparison to other polls that the left lost ground. But of course that’s not the right comparison to make. To be fair a better Dnes article published twelve hours later interviews the directors of the three major firms and uses their responses to compare the major polls, how they ask questions and why they differ. It also does a good job of looking at the consequences of the elections. But this is not an excuse, I think, for bad reporting of the results on the fly. It does not take a conversation with Kunstat, Hartl and Herzmann to have a sense of why polls differ or why an article should not report on more recent polls as if they are more accurate polls.

The mid-range parties are actually quite consistent in the polls, with KSCM around 13%, occupying an incredibly small range from 13.0% to 13.5%, while for the other parties the range is a bit wider: VV is around 11%, ranging from 10.2% to 12.6%, and TOP is around 12% with a wider range, from 10.4% to 14%. But the more important differences are at the top and bottom of the party scale.

At the top, CSSD produces two quite different sets of numbers–CVVM and STEM put it around 31% while Factum puts it at 26%–while ODS produces an equally large but more evenly distributed range of responses: Factum puts it a 23%, STEM at 21% and CVVM at 19%. In percentage terms these differences are not much bigger than those for VV or TOP, but in actual terms these differences are large enough to be crucial for determining the composition of the next government. At the bottom of the spectrum there is a small difference in the results for KDU-CSL–3.5 in CVVM, 4.5 in STEM and 5.5 in Factum–but a difference with extremely significant results. Not only does this difference of 2 percentage points represent about 50% of KDU’s average result, but it also means the difference between life and death for the party and perhaps for the coalition.

Given the significance of these two sets of numbers–they Are responsible for the difference between the “Left has majority” and “Left lost majority” headlines–it is time to do what the Czech daily press simply has not done (if any magazines or blogs have done it, I would like very much to hear about them), which is to examine the underlying math. To do this is more complicated than I would like.

Unlike Slovakia, where a single district makes calculation of seats from votes a simple exercise (which Markiza still managed to get wrong in 2006), the Czech Republic’s combination of many, differently sized districts and parties with varied regional strengths makes a quick estimation impossible. The best data, of course, would be a fairly significant sample size within each region, but since I don’t have that (and neither do most pollsters) or even a too-small sample size in each region, I am forced to rely on the large but dated data source of the last election. If parties’ regional strengths are consistent over time (and Kostolecky’s work suggests that they are), then we can guess what overall numbers mean for particular regions and calculate seat results on that basis. Of course we don’t have historical data for new parties and so I have made a guess that VV will have the same regional strengths and weaknesses as the Czech Greens in 2006 and that TOP09’s regional distribution will be an equal mix of ODS and KDU-CSL. Those aren’t great guesses but they do at least correspond to the ebb and flow charts a recent Dnes article (see right). I have no idea if this will work. We will see in a few days when I can plug in the electoral numbers and see if the 2006 regional distributions predicted those of 2010.

That done, we can then test various other assumptions, namely the relative performance of CSSD and ODS and whether KDU-CSL makes it over the threshold. The outcome is not unexpected but it is useful to take a look at the data which I present here in two formats: a color table and (because I can and have always wanted to) in a piece of (hard to read and pointlessly flashy) topography.

The simple take on this is that if KDU-CSL and ODS do well, there’s a strong possibility of a right wing government with a slight majority; if they do not do well, then they won’t be able to form a government and we’ll be in some odd realm of CSSD-led government where they key will be whether KSCM provides the (silent) supporting votes or one or more of the new parties fills that role.

More interesting are the other combinations: ODS does well but not KDU; KDU does well but not ODS. In the first case, it would appear that KDU in parliament is equal to a three point swing between CSSD and ODS. In other words, KDU brings as many seats as would a shift in the CSSD:ODS ratio from 29:21 to 27.5:23.5 (from a 7 point gap to a 4 point gap, which is about the same as the difference between Factum and STEM). As the experts relate in the aforementioned Dnes article, if KDU falls short, then a majority right wing government will require ODS to outperform all but the most favorable polls vis-a-vis CSSD and for TOP09 and VV to maintain their current levels. If KDU succeeds, then a narrow majority government becomes possible even with the ODS-negative results offered by STEM and CVVM.

Perhaps most remarkable result here is the renewed chance of deadlock of both CSSD and KDU do well: the amber “plain of indecision” on the graph above. It is remarkable that in the middle of the Czech Republic’s greatest period of volatility since 1992, one marked by the emergence of two new parties and the probable death of at least one other, the outcome in the middle of the possibility graphs is yet another 50-50 split, yet more deadlock.