A third post on the Czech election. There is a lot to say. I will begin by not quite rejecting the strong temptation to direct criticism to Dnes for celebrating the record high number of women in the new Czech parliament by adorning the article with a drawing of a topless woman and then inviting its readers to vote for “Miss Parliament” based on electoral headshots (I feel compelled to include the link just to prove I’m not making this up, but please don’t go there). It is enough to say, perhaps, that this is sexist even by Central European standards .

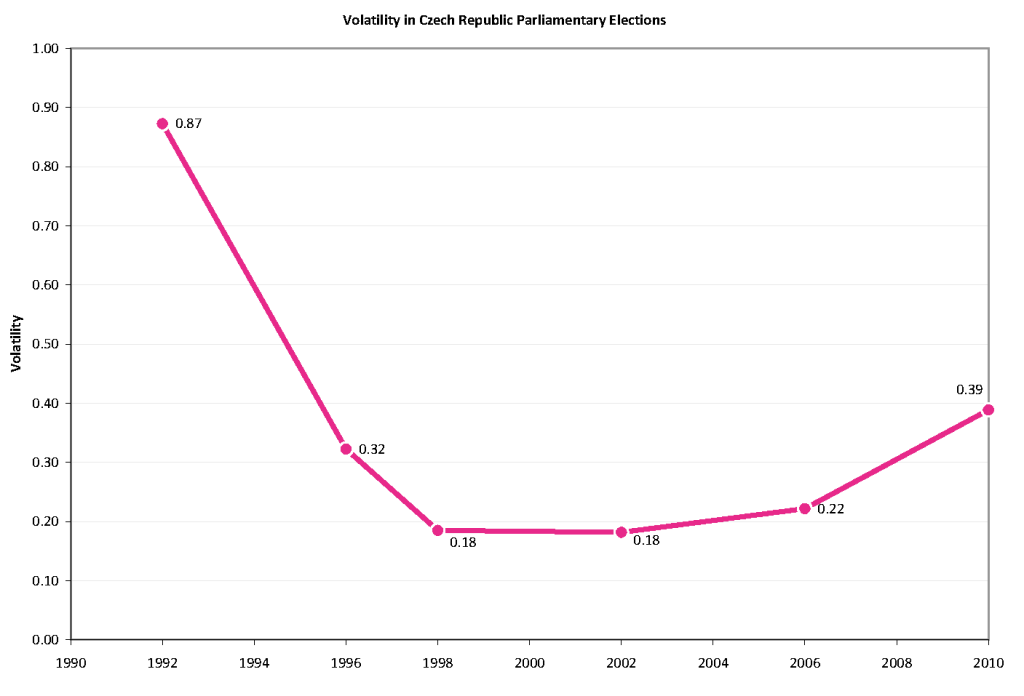

Instead I will focus on the question of volatility. In yesterday’s post I plotted Czech volatility over time but did not have time to use the right methods or comparison set. Now that vacation is over, I can fill in the gaps.

First, I can provide references to the articles I cited: the two best recent works I know on volatility:

- Scott Mainwaring, Annabella España, and Carlos Gervasoni, 2008, Extra System Electoral Volatility and the Vote Share of Young Parties, http://www.cpsa-acsp.ca/papers-2009/Mainwaring.pdf

- Eleanor Neff Powell and Joshua Tucker, 2009, New Approaches to Electoral Volatility: Evidence from Postcommunist Countries, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1449112

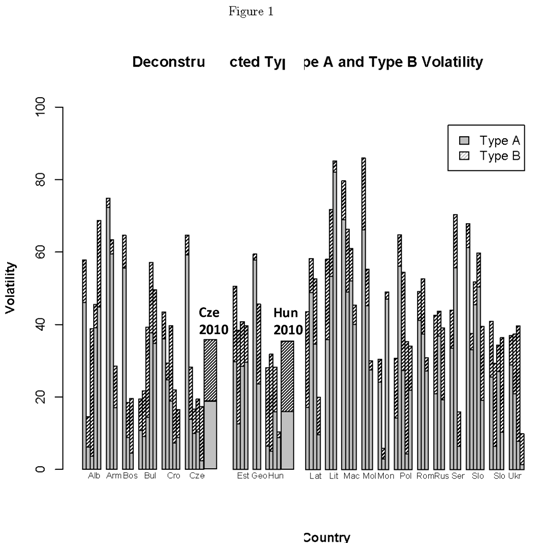

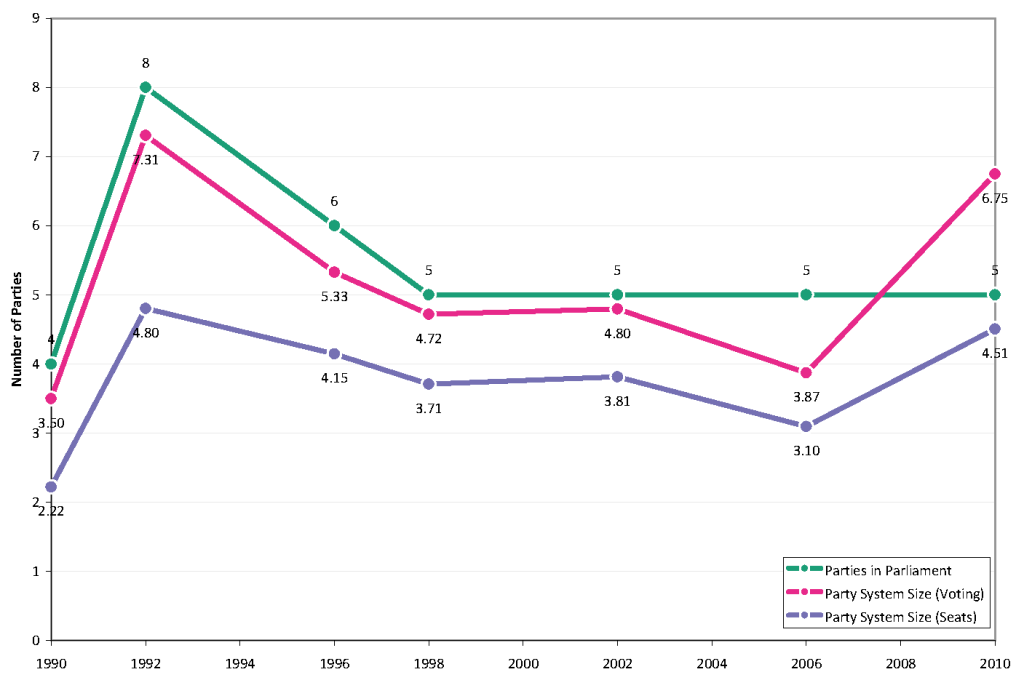

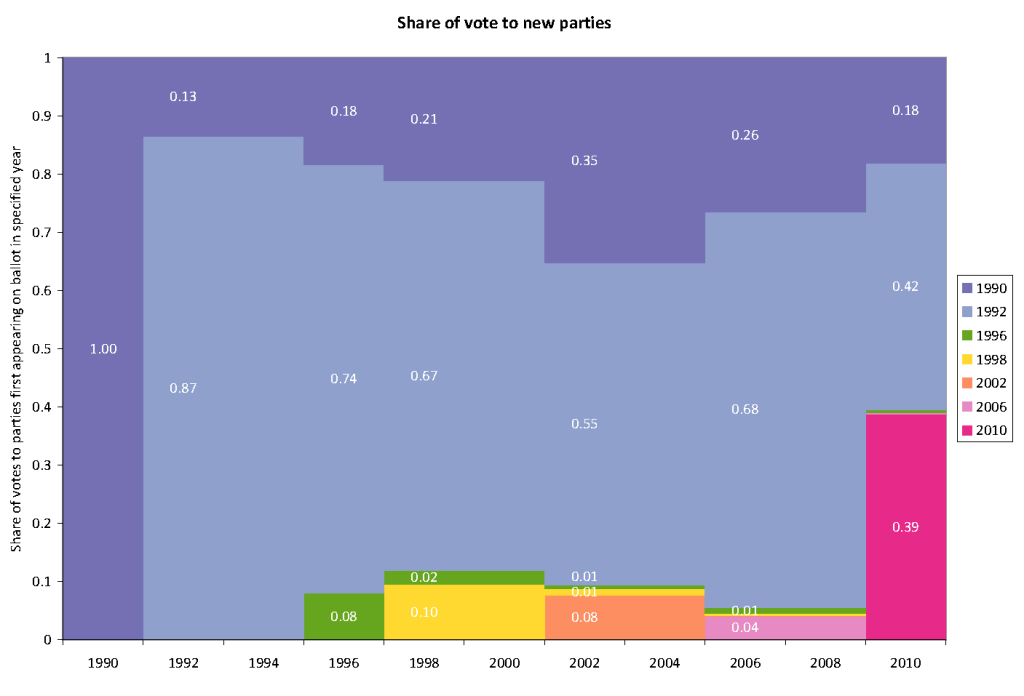

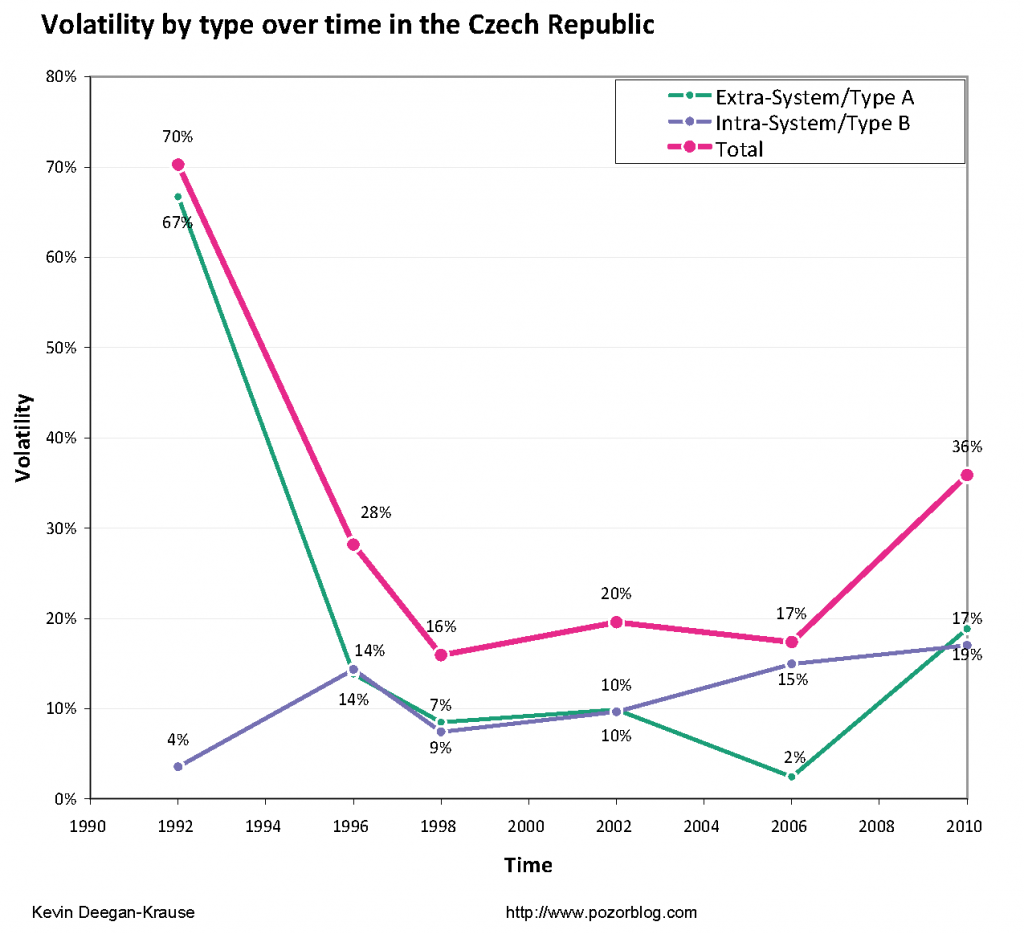

Because Powell and Tucker provide time series data, I will focus on theirs here, but Mainwaring et al handle the question beautifully as well (particularly their focus on “young” as opposed to strictly “new” parties). My first task was to take the Czech electoral data and use it to distinguish between volatility among existing parties (Mainwaring et al call this intra-system; Powell and Tucker call it Type B) and volatility created by parties entering and leaving the party system (Mainwaring et al call this extra-system; Powell and Tucker call it Type A). Using Powell and Tucker’s method (slightly different from my rough cut yesterday because it excludes parties with less than 2%) produces the following graph which decomposes the red line into its

From this it becomes clear that with the exception of 1992 (when extra-system volatility was huge because of the breakup of Civic Forum and seversl other parties) and 2006 (when extra-system volatility was basically absent), the Czech Republic has had both types of volatility in roughly equal levels.

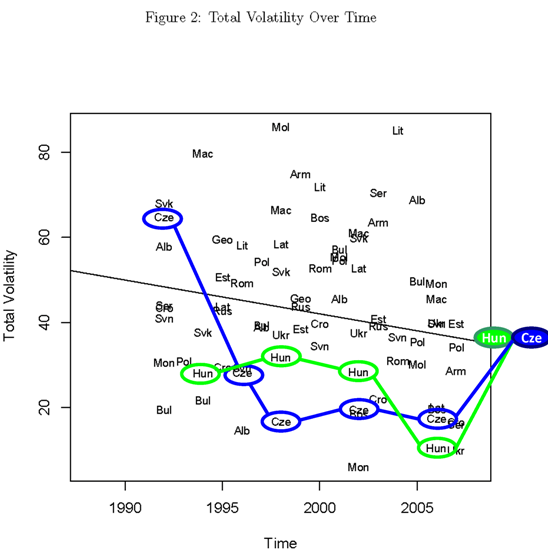

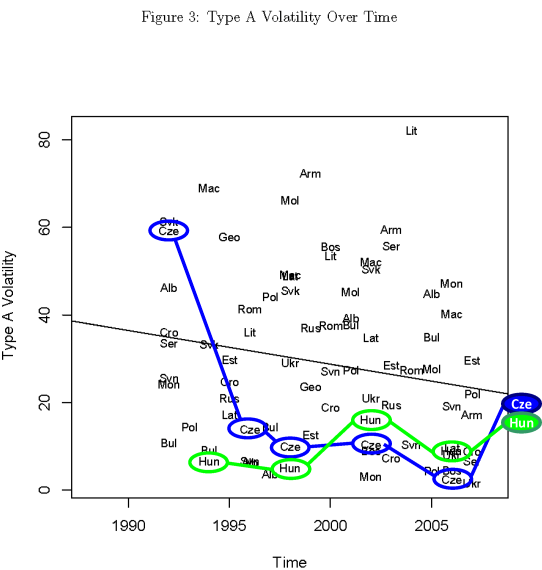

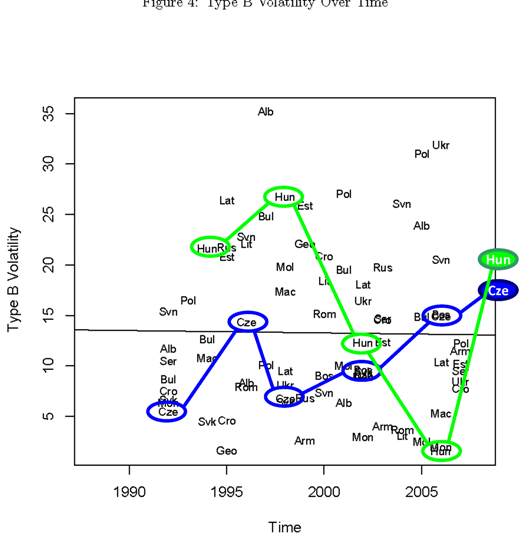

These levels are low not only with regard to the first electoral period but also with regard to the region as a whole. To convey that point, I steal figures from Powell and Tucker’s 2009 analysis, circle the Czech Republic, and insert the 2010 data. For comparison’s sake, I do the same for Hungary (and in two weeks will do the same for Slovakia). The results are as follows, with the Czech Republic in blue and Hungary in green.

By comparison with the region as a whole, both the Czech Republic and Hungary have exhibited low levels of both types of volatility; indeed in most election years during this period, these two countries have been at or near the lowest overall. On specific kinds of volatility, both Hungary and the Czech Republic have only occasionally been above average on intra-system volatility and never (since 1992 in the Czech Republic) above average on extra-system volatility. In 2010, however, their levels of intra-system volatility rise above the regional average, but so did the previously extra-system volatility, pushing the overall levels from the near the bottom to slightly above the regional trendlines.

In addition to the quantitative resemblance, there are also other similarities.

- First, both elections show a clear exhaustion with those in power that is clearly motivated by a general disillusionment with large segments of the political elite. Both the Czechs and the Hungarians had, for the most part, avoided this for some time, with large numbers of disillusioned voters holding their noses and voting for old parties anyway or switching to the other big party (accounting for the not insignificant levels of intra-system volatility). The higher levels of extra-system volatility in both countries suggests that these tendencies have diminished and that these two countries have moved closer to the Central European norm of disillusioned voters shifting to new parties.

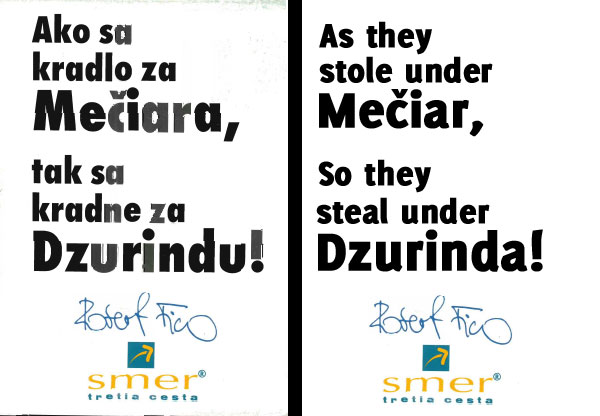

- Second, related to the above, both countries saw the emergence of a culturally liberal party attractive to younger, educated voters making extensive use of social networking software: LMP in Hungary, VV in the Czech Republic. (It seems to my uneducated eye that the Hungarian variant is economically more statist, but this seems relatively unimportant to the overall profile.) It is significant that a nearly identical party–SaS in Slovakia–looks set to take a similar share in Slovakia, and that similar parties have done well in the Baltics. There is here something new, not exactly a new party family (though in their cultural liberalism and anti-corruption emphases they share significant elements) and not exactly a new party type (though their methods and organization do not fit fully with any of the currently hypothesized models, even cartel and firm models), but with strong and intersecting elements of both. Nor is it unique to Central Europe alone but elements of it have emerged also in the West. Expect to hear more on this question in this blog. This is something that will need explanation.

Despite these similarities, it is important to emphasize that the election results in these two countries also differ in ways that are quite instructive:

- First, in Hungary the intra-system volatility represents the evisceration of one major party at the hands of the other–MSZP dropped while Fidesz rose–while in the Czech Republic, all of the established parties lost support compared to the last election.

- Second, although both countries saw the emergence of new parties, there is a very big difference between the center right TOP09 in the Czech Republic the far more radical right Jobbik in Hungary. This difference is important not only for the political content of the two parliaments (something we see already in the legislative output of the Hungarian parliament) but also for future volatility: a party with a clear programmatic message such as Jobbik may be able, despite its internal factionalization, to survive multiple election cycles whereas the more diffuse TOP09 may have a harder time of it (though because I have just predicted that it will turn out not to be true).

- Third, there is a significant difference in the role of these new parties: Jobbik will be able to remain outside of government whereas TOP09 and perhaps VV will likely be part of government. Both positions have their risks: Jobbik may be able to avoid responsibility but will also be able to claim few accomplishments and has already had the softer parts of its agenda on national questions pulled from underneath it by the current government. TOP09 and (probably) VV will be able to implement parts of their agenda but will also become responsible for any resulting problems (even those they merely inherit) and will face problems when their new (and relatively inexperienced) cabinet ministers succumb to the same clientelistic temptations as their predecessors. It is interesting to me that VV has openly contemplated staying out of government, suggesting that it has learned the lesson of past Czech “new” parties and those elsewhere in the region. (As Tim Haughton and I have argued elsewhere: new anti-corruption party + government participation = death)

What happens in Hungary and the Czech Republic as the result of these elections will not, I think, have much impact on the broader world (and may not even have much impact on the quality of the daily lives of Hungarians and Czechs) but they are worth this degree of close scrutiny (and more) because what is going on there is indicative, I think, of significant transformations in the relationship between who people are (demographically), what they think (attitudinally) and who they vote for (politically). Demographic patterns and attitudinal patterns still exist but their relationships to political behavior have changed as perceptions of corruption have risen to the top of the list of concerns (and “endurance” becomes shorthand for “corruption”) and as political entrepreneurs take advantage of this change and of new organizational technologies to provide an ever changing menu of new parties (themselves organized primarily for short term gains). For awhile the Czech Republic and Hungary offered some evidence that the trend was not inevitable. With the most recent elections in these countries, it is more difficult to see any alternative.

Finally, from the broader perspective it is interesting that in Hungary and the Czech Republic the election has been regarded as a fundamental shift, a major change in the game of politics despite the fact that the degree of shift was, by regional standards, only about average. Perhaps earthquakes only seem major if you are not used to them, but they still shake buildings. Of course people and institutions figure out ways to survive even where earthquakes are a regular occurance, but their lives are different than they would be in areas with less seismic activity (money is spent differently, personal habits follow different patterns). I hope to spend a good portion of the next few years thinking about how political life is different when every election is an earthquake.

FOLLOW-UP ON PREVIOUS POSTS:

Ben Stanley commented via Facebook: “It’s great being a CEE specialist. Instead of accumulating common wisdoms, we get to throw them all away and make up new ones!”

Cas Mudde comented via Facebook, “Would be interesting to see the same for seats in parliament.”

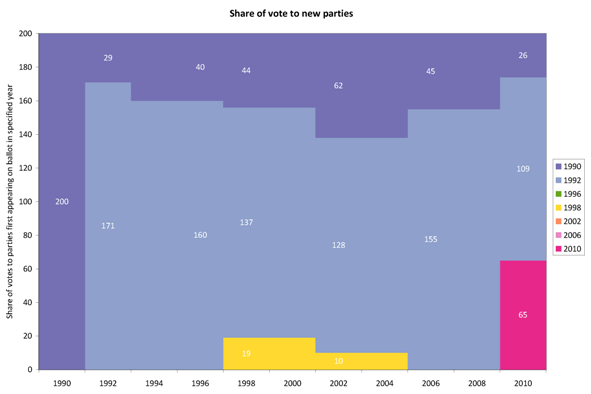

Here it is, though it is actually rather uninteresting compared to the same calculations with votes. It suggests, however, that one of the reasons that new parties do not survive is that they never really get started. US, VV and TOP09 are the only new parties actually to have made it over the threshold since 1992, but this rather technically excludes the Green Party, SZ whose 2006 incarnation is difficult not to describe as a new party despite a certain degree of legal and organizational continuity with the one established shortly after the revolution of 1989. It will also be interesting to see if, as Sean Hanley wonders, Suverenita manages to use its stronger-than-expected performance to chip away at CSSD in the next election cycle, thus enhancing (or if VV or TOP09 fare badly, maintaining) the red “2010” bar.