/* Style Definitions */ table.MsoNormalTable {mso-style-name:”Table Normal”; mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0; mso-tstyle-colband-size:0; mso-style-noshow:yes; mso-style-parent:””; mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt; mso-para-margin:0in; mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:10.0pt; font-family:”Times New Roman”; mso-ansi-language:#0400; mso-fareast-language:#0400; mso-bidi-language:#0400;}

While I do not often write about particular political statements, I am drawn to comment on today’s response by Robert Fico to Mikulas Dzurinda’s accusations that the government has failed to tap Eurofunds.

While I do not often write about particular political statements, I am drawn to comment on today’s response by Robert Fico to Mikulas Dzurinda’s accusations that the government has failed to tap Eurofunds.

I translate Fico’s statement as follows (and would appreciate any better translation):

My political conscience cannot be a person like Mikulas Dzurinda, who lies from morning until night. He gouged us, surrendered our economy to foreign monopolies, evidently bought members of parliament. A person who never wanted Slovakia, did not vote for the constitution of Slovakia or for sovereignty. I will never respond to such a person, ” said Fico

“Mojím politickým svedomím nemôže byť človek ako Mikuláš Dzurinda, ktorý od rána do večera cigáni. Vydieral nás, spôsobil odovzdanie ekonomiky tohto štátu cudzím monopolom. Preukázateľne kupoval poslancov Národnej rady SR. Človek, ktorý nikdy nechcel Slovensko, nehlasoval za Ústavu SR, zvrchovanosť. Tohto človeka nikdy nebudem komentovať,” povedal Fico.,Pravda, 6 August 2009

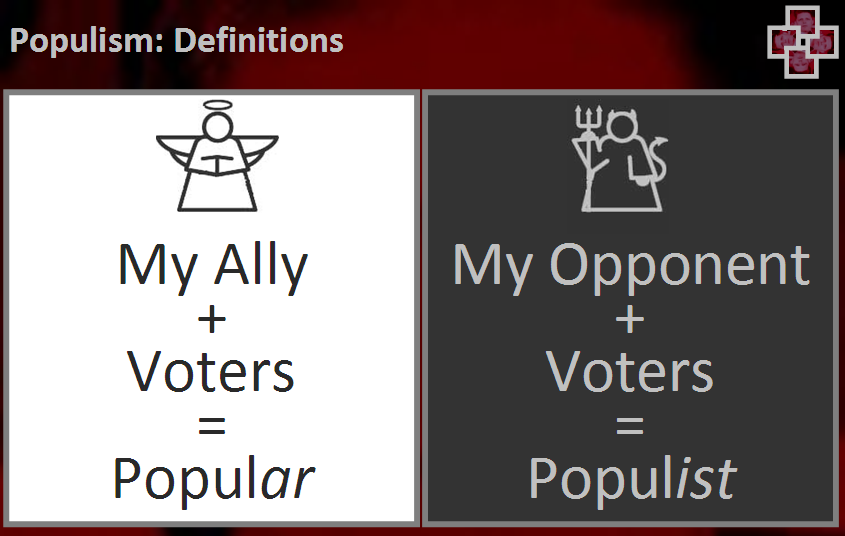

I have no interest in taking sides in this controversy, but the nature of the comment is worth some attention because, as sometimes happens (quite often in fact), a politician’s off-the-cuff remarks do an excellent job of summarizing how they think—and we too should think—about political competition.

Fico’s response follows this structure:

- A resolute moralism: “Dzurinda cannot be his conscience.” Fico is a man of strong moral opinion. He not only identifies his opponents as wrong, but also as morally flawed. This is not particularly unusual among politicians, but it is strong in Fico’s case. His is a tone of righteousness.

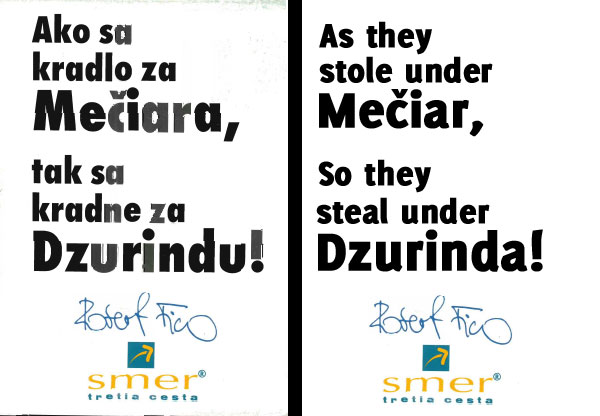

- An emphasis on corruption. Fico’s first observation about Dzurinda is that “he lies” Two phrases later, he reminds us of the scandals that were part of Dzurinda’s own period of government. These are important: not only was corruption an important theme for Fico (especially in 2002 but still to some extent in 2006) but his government’s own corruption scandals have caused the party to increase its emphasis on how bad corruption was under Dzurinda as a way of minimizing the current problems.

- An emphasis on economic injustice: “He gouged/stole.” Fico’s best theme has been the overreach of Dzurinda’s economic reforms. He has played this well and here he ties it in with the lying so that Dzurinda’s economic reforms presented not simply a different and incorrect economic formula but one which Dzurinda used for his own gain and with wanton disregard for (or indeed active malice against) the average Slovak.

- An emphasis on patriotism. Dzurinda not only hurt the economy but he did so deliberately to the benefit of foreign interests. Two phrases later Fico suggests an even deeper lack of national feeling in Dzurinda dating back to the early 1990’s. Dzurinda did not vote for the constitution (the final formal step toward independence), did not support “sovereignty” and did not even “want Slovakia” (phrasing which implies an even deeper antipathy than saying that he did not want “want an independent Slovakia.” The vehemence of this critique should not surprise me, but it does, as it is so deeply resonant of the critiques of Dzurinda’s then-party, KDH, in the 1990’s by Meciar’s HZDS (back when Dzurinda was a minor player), and particularly the word for sovereignty, “zvrchovanost” which had a particularly strong resonance for Meciar and his supporters. Meciar sometimes (though admittedly less frequently) applied similar critiques of lack of patriotism toward Fico’s then-party, SDL (back when he was a minor player). Now Meciar is all but out of the game, and it is Fico who is applying the critiques to Dzurinda.

All of fits nicely with what many of us have discussed and claimed: Slovakia’s party system has at least two dimensions—one economic, one national—and the last 20 years have been a competition to see which one would be most important. Meciar turned the axis in the direction of the national and held it there for most of the 1990’s. Dzurinda turned it back primarily to the economic and held it there for the first half of the 2000s, with Fico providing a big assist. Now in government, Fico has sought to shift the basis of competition by a half turn, linking the economic with the national so as to produce a single axis of competition between pro-national, economically statist parties on the one hand and non-national, pro-market parties on the other hand. The positions of the players differ slightly: The Hungarian parties push hard on national issues and care little about economics (but tend to be a bit more market oriented, a legacy from its past coalition partners and internal debates) whereas SDKU pushes some economic questions and stays away from national issues at all costs. On the other side SNS pushes hard on the national side and cares little about economics whereas Smer still pushes economic questions and plays slightly softer and more socially acceptable national issues. Whether this is permanent is an open question (like all questions I ask about Slovakia’s future…I’ve been wrong too many times), but for the moment Fico has hit on a winning formula and has no need to change it.

Other issues fight for prominence—some in KDH and all in KDS would like to see an emphasis on moral values, new parties and some in Smer continue to emphasize corruption—but these have yet to take hold in a fundamental way. The values question probably has too little traction, for most Slovaks outside the (demographically declining) population of believers. The corruption question is too hard to sustain because parties that get into power have a difficult time staying clean (and would have a difficult time persuading voters that they had stayed clean even if they could).

Finally, two off-topic (but maybe not so minor) points:

- It may or may not be a coincidence that he uses almost the same formulation—“from morning until night,” that Hungarian premier Gyurcsany used to describe his own party’s actions. Comparing Dzurinda to a Hungarian would be a nice touch, but it may simply be a coincidence.

- I am slightly shocked by Fico’s use of the word for lying—“ciganit”—which, though I may be mistaken, I do not recall hearing often from the mouths of politicians. Not only is this particularly rough language but its relationship to the slang term for Roma, “cigan” makes it potentially problematic. I know the word has taken on something of an independent existence in Slovak (much as “gyp” did in English) but it is hard to avoid the connection and it seems to be a word to avoid using. It is perhaps particularly troubling to me because at a language law rally outside of parliament in 1995 I overheard a Meciar supporter talking to a friend about Dzurinda (at that moment speaking on the floor of parliament against the restrictive language law) and saying “Did you know he’s a Gypsy? (“cigan”). Fourteen years later Slovakia has a new, relatively restrictive language law and Dzurinda is again likened to a “cigan” in the worst sense of the word.