(or why Dr. Sean hits the nail on the head)

Kudos to Sean Hanley for his recent post, Do Slovak and Czech Christian Democrats have a prayer? Dr. Hanley, whose blog (Dr. Sean’s Diary, http://drseansdiary.blogspot.com/) has long been my model for public, academc discourse on postcommunist Europe, yet again calls attention to precisely the questions I am trying to think about. Not only does he do an an excellent job of covering the dilemmas of the Christian Democrats in the Czech Republic, a realm that nobody knows better than he, but he also offers provocative thoughts about intra-party struggles, coalitions and election results in Slovakia:

And generational renewal? Commentators and politicians in CEE are always harping on about this, but it’s hard to see quite newer or younger will necessarily mean better. Such comments are, usually a disguised call for in political renewal or cleaner, better, more liberal government – amen to that, but even though there is no primaries system there is ample scope for new parties to emerge or young technocrats to parachute themselves into organizationally weak, elite-led parties. The Slovak experience suggests that many voters don’t want renewal of this kind, but stability. Is the Slovak Barack Obama actually Robert Fico?

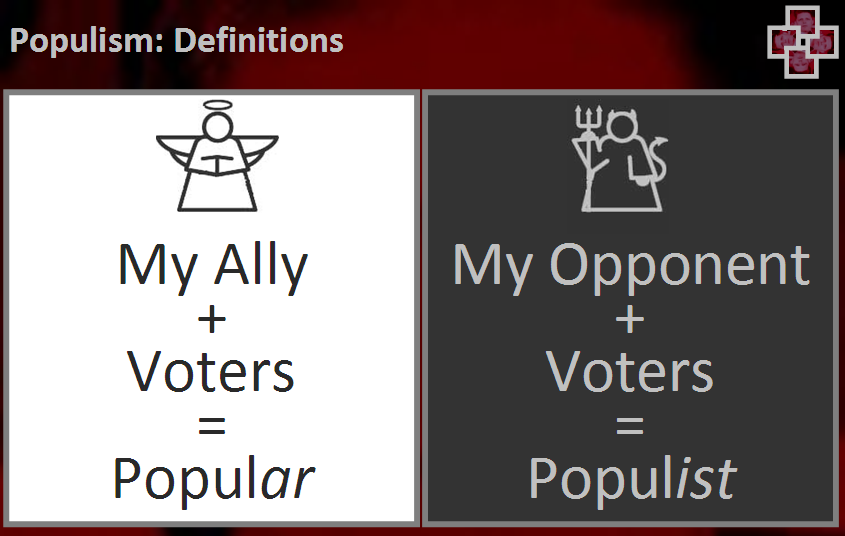

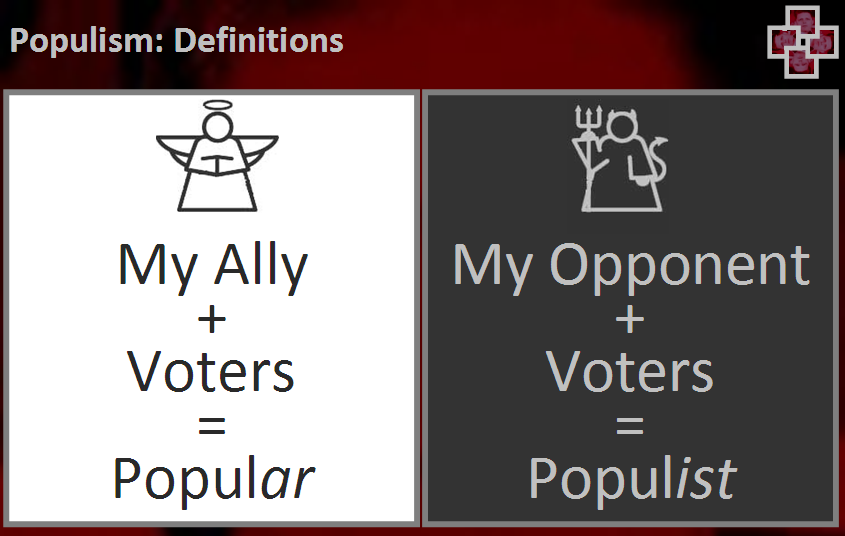

Though the comparison may not be desirable to some partisans of Obama or of Fico, there are important similarities that must not be overlooked. I continue to wrestle with the concept of “populism” since in its common usage it is both vague and highly normative:

Populism

But if populism does mean anything–and I think it does mean something despite all of the accretions over time–it is a sense that politics is broken. It is a feeling (though not quite an ideology) that those in public office–both those in power and those in opposition–are the cause of the problem. By this standard, of course, nearly every American politician is a populist, but if you compare them to many of their European counterparts, that is actually a fairly accurate characterization. While I have not done the spadework to explain why, I suspect that America’s relative exceptionalism in this regard has a lot to do with its presidential system, the dominant role of media, the relative absence of party organization. Many European countries are moving in this direction, however and postcommunist Europe appears to be in the vanguard. In this sense, both Fico and Obama have become preferred choice for those voters who are tired of “politics as usual” and who seek something different. Those are different kinds of voters compared to their overall electorates, but that is a different story.

Party renewal

There is a lot more to say about the question of populism, and I hope to do so over the coming months. In the meantime, however, I want to point out one very important difference between Obama and Fico and one that goes to the heart of Prof. Hanley’s question: Barack Obama is still a member of the Democratic Party and it is hard to imagine him leaving the party if he loses the nomination; Robert Fico, on the other hand, left his original party and formed a new one.

Fico is not alone in this. Indeed questions of internal-party change and party defection are central to the course of Slovakia’s politics and to the politics of many countries in the region. Dr. Hanley is right to point out that the question is not whether parties can achieve generational change; renewal can easily occur within a single generational cohort. Rather, the question is whether renewal can occur within a single party. Two phenomena mark Slovakia’s political party system: the relative infrequency of institutionalized leadership change and the relative frequency of party splits and splintering.

Loyalty: The Rarity of Party Leadership Change

Parties in Slovakia rarely change leaders and they almost never undergo institutionalized leadership transitions. Among Slovakia’s current parliamentary parties. As the table below shows, the average tenure of the chairmen of Slovakia’s current parliamentary parties is between 8 and 9 years (depending on the method of calculation), and this represents an average of 67%-71% of their parties’ respective lifespans.

| Party |

Founding Date |

Number of leaders since founding |

Current leader |

Date assumed leadership |

Duration of leadership |

Length of leadership as % of length of party existence |

| Party of the Hungarian Coalition (MKP/SMK) |

1990 |

2* |

Pal Csaky |

2007 |

1 year |

6% |

| Christian Democratic Movement (KDH) |

1990 |

2 |

Pavol Hrusovsky |

2000 |

7 years |

41% |

| Slovak National Party (SNS) |

1990 |

5 |

Jan Slota |

1994 |

9 years/13 years** |

53%/76%** |

| Movement for a Democratic Slovakia (HZDS) |

1991 |

1 |

Vladimir Meciar |

1991 |

16 years |

100% |

| Smer |

1999 |

1 |

Robert Fico |

1999 |

8 years |

100% |

| Slovak Democratic and Christian Union (SDKU) |

2000 |

1 |

Mikulas Dzurinda |

2000 |

7 years/9 years*** |

100% |

| Mean scores |

1993 |

2 |

– |

1999 |

8-9 |

67%-71% |

http://www.terra.es/personal2/monolith/slovakia.htm* Party formed from merger of Hungarian Christian Democratic Party (MKDM) and Coexistence in 1998

**Jan Slota rejected his removal in 1999 and formed the rival “Real” Slovak National Party (PSNS) during his period out of leadership in SNS.

***Mikulas Dzurinda led the Slovak Democratic Coalition before leading the SDKU |

Indeed three parties, Smer, SDKU-DS and HZDS (which together hold almost 2/3 of the deputies in parliament), have had the same leader for their entire existence. The same is true in practice for several significant parties that are currently no longer represented in parliament (ZRS, ANO). Other parties have undergone leadership transition by default as founding party leaders became president (SOP, HZD) or withdrew from politics (KDH). Only a handful of parties have enjoyed (though for them, “enjoy” may not have been the right word) contested leadership struggles that actually changed the course of party leadership. The Party of the Hungarian Coalition (MKP/SMK) resolved internal leadership questions when it formed from its component parties in 1998 and underwent a leadership shift again in 2007. The Party of the Democratic Left (SDL) underwent major leadership transitions in 1996 and 2001. The Slovak National Party (SNS) is the closest to demonstrating regular leadership change (1990, 1992, 1994, 1999, 2003) but change in party leadership after 1992 has been fraught with difficulty and appears for the moment, to be at an end.

Exit: The Frequency of Party Splintering

New party leaders in Slovakia are more likely to be leaders of new parties than new leaders of old parties. Whereas the six parties listed above have collectively only experienced seven or eight leadership changes (depending on calcuations), they have collectively experienced at least ten significant splits and splinters of parliamentary deputies or prominent party leaders. Secession is far more common than succession. It is difficult to find struggles between party incumbents and party insurgents that have left a party intact: SDL in 1994 (to the extent that Peter Weiss’s withdrawal was not entirely voluntary), SNS in 1992 and 2003, and MKP/SMK in 2007. Far more common is struggle followed by departure of the loser to form a new party: SNS in 1994 and 1999, SDL in 1999 and 2001 (and, to the extent there was a real struggle, with the departure of Luptak in 1994), KDH in 1991, 2000 (related to the dissolution of the SDK coalition) and 2007 (just last week, in fact), SDKU in 2003 and the seemingly annual HZDS splinters in 1993, 1994, 2002, 2003, (and in miniature formjust recently). In fact the only parties in which party struggles have not led to departure are the Hungarian Coalition (which is limited by the inability of Slovakia’s 11% Hungarian population to support two parties that can overcome the 5% threshold), new parties that have died before a split could occur (SOP, ANO, ZRS) and a variety of smaller parties that never by themselves passed the 5% threshold (indeed Slovakia’s small parties such as the show more robust leadership rotation and a greater ability to survive leadership struggles, perhaps because they are too small to lose any members without disappearing entirely. See The People’s Front of Judea).

Why do Slovakia’s parties splinter so easily? This is a complicated and fascinating question that I am currently working on in greater detail. Institutional barriers to entry for new parties are low, but not much lower than in other parliamentary/proportional-representation systems in Europe. A stronger answer may lie in perceptions of cost and benefit. The perception of departing may be relatively low in Slovakia because certain splinters have demonstrated electoral success (DU and ZRS in 1994, Smer in 2002) and other parties have demonstrated an ability to go from nowhere to election in a matter of months (SOP, ANO). I do not, however, have the evidence to say whether these cost perceptions are lower than in countries with fewer splinters. The second part of the answer may lie in the perceived costs of remaining within a party. This in turn relates to the perceived absence of voice.

Voice: It’s (Not) My Party

My initial observations suggest that Slovakia’s centralized party organizations make it difficult for dissenters to remain. When parties remain in the hands of their founders, as in the case of Smer, HZDS and SDKU, or become tightly bound up with a successive leader, as in the recent case of SNS, those who wish to change the party may have no choice but to go elsewhere, particularly if they openly challenge the leadership. The strength of this conclusion is mitigated somewhat by the fact that even the more collegial SDL and KDH have produced a significant share of Slovakia’s splinters, and even some in the vulnerable Hungarian Coalition appear to have considered departure. Nevertheless, it is hard for me to believe that structures more conducive to internal democracies, structures that took party control out of the hands of the founder, could produce more renewal and fewer departures. I have not read Hirschmann in a long time, but it seems like introducing genuine opportunities for voice could provide an alternative both to frustrated loyalty and to destabilizing departure.

In this regard, recent discussions within the current opposition are a very positive sign. It would appear that the current infighting within parties that are already at a low point in their political fortunes will only make matters worse–and in the short run this is true–but in the long run, the kinds of discussions emerging among second-rank leaders in SDKU, KDH and MKP/SMK are potentially conducive to long-term survival, party renewal (much needed) and electoral success. By this standards the current governing parties have a short-term advantage in internal cohesion, but are at greater risk of long-term difficulties because they include some of the most centralized parties that Slovakia has ever seen. In terms of broader patterns, the news is good because it is potentially quite normal: parties in power put themselves at risk by failing to adapt; parties out of power learn how to renew themselves and eventually rise to the challenge. If Slovakia’s current opposition can manage to find mechanisms for voice and reform from within, Slovakia could experience the novelty (for Slovakia, at least) of an opposition-coalition struggle that is not also the struggle between old parties and new.