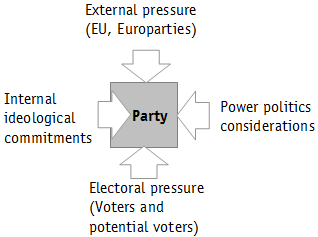

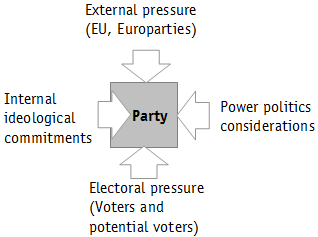

- The arrow on the left (pointing right) refers in this case and that of all subsequent diagrams refers to the realm of policy seeking and addresses a party’s overall policy preferences, broadly defined. These may depend on the preferences of the party leader or party leaders and activists together. They may be unified or divided.

- The arrow on the bottom (pointing up) refers to the realm of vote seeking and addresses the degree to which a party’s voters (and potential voters) support a particular step and the degree to which their preferences on that issue will shape their voting behavior

- The arrow on the right (pointing left) refers to the realm of office seeking and discusses the degree to which a party’s position on the issue will affect its ability to gain or keep political office and/or to influence the other aspects of office-related decisions.

- The arrow on the top (pointing down) refers to a fourth realm, often ignored in studies of domestic political behavior (often because it is not relevant) which addresses the degree of external pressure from international bodies, neighboring countries and other large institutions.

|

|

For each of the diagrams, the size of the arrow reflects the degree to which a particular factor is important in shaping a party’s position while the color of the arrow indicates the policy inclination of that factor:

- Green – for approving the EFSF expansion

- Red – against approving the EFSF expansion

- Amber – mixed or ambiguous

With these annotations, I would suggest that the factors within Slovakia’s party system looked roughly as follows:

Let’s start with the easy cases and work toward the harder ones. |

![ScreenClip [3]](http://www.pozorblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/ScreenClip-3.png) |

Slovak National Party (SNS)

SNS is a fairly easy party to assess in this regard because of its relative political isolation and narrow message.

- Policy. SNS will oppose anything that looks like transfer of authority outside of Slovakia’s borders and so opposition to the EFSF was a fairly simple position for the party, made easier by the fact that it can be argued to involve transfer of wealth from Slovakia to others “less deserving” and (this is genuinely a factor in the case of SNS) with swarthy skin tones.

- Votes. SNS might stand to gain in maintaining its opposition as the EFSF expansion has not gone beyond bare majority support in Slovakia’s population and because many of those who oppose the EFSF will not be attracted to other, more libertarian elements of the platform of the other EFSF opponent, SaS. SNS stands to gain perhaps a tiny bit from disaffected Smer voters (if Smer supports the plan on the second round of voting) and from any anti-EU non-voters who turn out to vote next time.

- Office. SNS has very little to lose in opposing the vote since it is openly regarded as uncoalitionable by the members of Radicova’s coalition and can return to government only in tandem with Smer. To the extent that this vote hastens early election and does so at a time when Smer is performing well and SNS faces a downward trend but has not yet fallen through the 5% threshold in most polls, (and also may hope to get the jump on the very recently-registered competitior Nation and Justice [NaS] rather than giving it time to develop) the current political circumstances give the party an incentive to oppose the EFSF expansion even if policy and electoral motives did not.

- External Pressure. SNS has no real partners abroad–indeed that would violate its basic tenets–and therefore is not subject to any pressure to go along.

All of this makes SNS’s “no” decision quite easy. It was the only party whose members actually voted “no” rather than abstaining or absenting themselves. |

|

|

![ScreenClip [4]](http://www.pozorblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/ScreenClip-4.png) |

Slovak Democratic and Christian Union (SDKU)

SDKU, almost despite itself, faces pressures in favor of the EFSF. Things would be a lot better for this party if the issue had never arisen. But it did…

- Policy. SDKU has been one of the strongest supporters of European integration in Slovakia, and has pushed an integration-favorable policy at nearly every opportunity. It has once in the past used an EU vote (the Lisbon Treaty) to force government changes when in opposition, but it was clear to note that it was a tactical move and that the party did not oppose the Treaty itself. The party is therefore oriented toward going along and getting along with its European neighbors

- Votes. SDKU’s voters tend also to be among the most pro-Euro and pro-European in the country and it would be difficult to explain a “no” vote even if it were done for the sake of expediency. The party’s voters also tend to have strong business or cultural relationships with the rest of the EU and might be expected to support cooperative decisions.

- Office. SDKU had little choice but to push this initiative, because to fail to do so once it was on the table would be to abandon any claim to leadership of the coalition. In the end, the party was probably chose to risk tying the vote to a vote of confidence in the government, because the alternative–losing–would have been a de facto (if not de jure) vote in the same direction. Staying in office–and staying in control while in office–were already put on the table as soon as this issue became significant.

- External Pressure. EU pressure plays a strong role–and would have played a strong role regardless of the party affiliation of the person who sat in the Prime Minister’s chair. The PM more than anybody else faced the direct pressure from abroad, and the direct responsibility for the decision. To abandon support for the EFSF when (as Radicova noted in her speech on the day of the vote) 16 other parliaments had said yes would have been extremely difficult and tantamount to self-exile from Europe. Radicova faced pressure not only from its party group in Brussels but directly from heads of state across the region. This would be a difficult force to oppose for any premier (and while it is an untestable hypothesis, even Fico might have bowed to this pressure at the expense of other goals.

Radicova faced pro-EFSF messages in every direction, particularly from the one source–abroad–that she faced more prominently than anybody else. |

![ScreenClip [5]](http://www.pozorblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/ScreenClip-5.png) |

Christian Democratic Movement (KDH)

KDH tends to work closely with the SDKU, though not always–and they themselves have been responsible for a past vote of no confidence (though in that case it came at the end of a term and merely shortened the government’s duration by 3 months). KDH faced similar pressures to those of SDKU but much lighter.

- Policy. KDH has not always been pro-EU on every issue, but the objections have tended to be cultural rather than financial, and KDH chair Jan Figel served previously as a European Commissioner and therefore tends to have strong ties with Brussels. This perhaps does not amount to a sufficient cause to vote for the EFSF but it certainly helps.

- Voters. KDH voters likewise have expressed some disillusionment in the EU but as religious conservatives rather than as fiscal conservatives. The party’s voters tend to think of themselves as Europeans (even if they have a slightly different idea of the meaning of “Europe.” Its voters likely would have demanded an explanation for a “no” vote, though it is possible to envision a plausible response that would not have cost many voters.

- Office. As a junior coalition partner, KDH could have maintained its position with any vote that satisfied SDKU, but to the extent that SDKU needed a “yes,” so did KDH. KDH has ruled out coalition with Fico and does not seem to change its mind any time soon.

- External Pressure. While not in the prime ministerial hot-seat, KDH has fairly close relationship with the European People’s Party and Figel has close ties to the European Commission, so external pressure might have helped keep the party supportive even if other factors did not point in the same direction.

While not as vulnerable on the issue, KDH faced incentives similar to those of SDKU and remained loyal on this question. |

|

Most-Hid (Bridge)

Parliamentarians of Most-Hid also remained supportive of the EFSF, though if KDH’s reasons were a weaker reflection of SDKU’s, Most-Hid’s were weaker still.

- Policy. Most-Hid’s primary policy concern is Hungarians in Slovakia and this issue had little to do with that one, so the party had only residual “pro-Europe” policy sentiments to fall back on. Those might have been enough even if there were no other influences.

- Voters. Most-Hid’s voters are not likely to shift their vote because of this issue and so the party is not much affected in this regard.

- Office. Most-Hid, like KDH, depended on SDKU’s remaining in office. While it is not inconceivable that Most-Hid might form a coalition with Smer, it is unlikely, and it would require the absence from parliament of a Smer-friendly partner such as SNS. Most-Hid thus needs the current coalition for its office-related goals and depended heavily on the decisions of SDKU.

- External Pressure. Like KDH, Most-Hid has fairly close connections with the EPP and probably faced a bit of pressure in that regard, though it likely was not decisive.

Also part of the Most-Hid parliamentary club were 4 members from the Civic Conservative Party, ethnic Slovaks who had at best a loose relationship to Most-Hid itself. Of these one opted to support the coalition while the other three

|

| So much for the relatively unconflicted parties. Two other parties evince a more mixed structure of incentives, which I try to lay out below. |

![ScreenClip [2]](http://www.pozorblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/ScreenClip-2.png) |

Freedom and Solidarity (SaS)SaS faced perhaps the most difficult choices in this conflict but after a considerable time in negotiation ended up opting for its initial policy orientation (though this may not have hurt its voter orientation–we shall see)

- Policy. From the beginning SaS announced its opposition to this bailout and it intensified its position over time, finally issuing an elaborate statement that called this “The Road to Socialism.” It would appear that party leader Sulik genuinely regarded the EFSF as both a moral wrong (taking from the disciplined and giving to the lazy) and a practical mistake (since it wouldn’t work anyway). Moral absolutes played a big role in his prounouncements and offer the best explanation for the party’s decision to hold its ground.

- Voters. Here the matter is more complicated and tied up with the office seeking goal, but the policy seeking goals should not be too sharply distinguished from the desire to appeal to voters who share those goals (and to prevent the exodus of those already supporting the party). Sulik’s voters, while pro-Europe in the geographical and cultural sense, are not necessarily pro-European Union in the political sense (not unlike Vaclav Klaus in the Czech Republic), and by taking this course he may have cemented some of those relationships. And since Sulik expects the mechanism to fail in practical terms, he may also expect that come March he will have a strong “I told you so” position on which to run (Thanks to Tim Haughton for bringing this aspect to my attention). Securing voters is especially important for a party that started its life at 12% and quickly fell to around 7% (and lower in some polls) and has seen other similar parties around the region fail to return to parliament. Having an issue that can cause voters to overlook the lack of other accomplishments (which are hard in a coalition government) and having elections sooner rather than later may allow SaS to stave off the “new-party-in-government” curse that has killed ZRS, SOP and ANO in Slovakia and many other new parties in other nearby countries. The downside, however, is that in order to achieve this SaS had to be the one to bring down the government, which will leave it in bad odor with some even as it boosts its appeal with others. The question is which will prevail. For Sulik, I suspect the calculation was that voting no (even if it meant bringing down the government) would be an electoral plus (or at least electorally neutral).

- Office. Even if this is an electoral plus, it must be understood at best as mixed in the realm of office seeking. To bring early elections and provide itself with an issue, SaS had to end the only government that it could be part of, and do so at a time when that government’s overall poll ratings make it extremely likely to win the next election (more on that in the next post). SaS may survive the next election, but it will not return to the government posts that it seeks unless the current government manages to overcome Fico’s popularity (something that won’t be helped by the collapse of the EFSF that Sulik may expects). Even if this happened, Sulik would also need the parties of the Radicova government to offer some sort of amnesty. At present this seems far from likely, though it is hard to imagine that they would not relent if Sulik’s party held the balance of power in the next government. Sulik’s oddly generous remarks about Radicova after the vote suggest either that he does not understand the intensity of feeling of the other side or that he is preparing the way for return to the fold, or both.

- External pressure. Unlike all of the other parties in Slovakia’s parliament except SNS, SaS does not have the formal presence of a Europarliament deputy in a well-organized European party structure. It’s membership in the European Liberal Democrats thus has relatively little immediate impact (and a request from ELDR to change positions had no impact).

The actions of SaS here will significantly change its electoral and coalition parameters, though whether for the better remains to be seen. Much may depend here on the actual success of the EFSF and of Smer. If both perform poorly, Sulik may be in a position to return to government (albeit in bad odor), but if either does well, his chances for returning the party to the political position it had on 10/10/2011 will be much smaller.

|

| Finally, there is one party in all of this that must be regarded, in the short run at least, as the big winner. This party, too, had mixed incentives but managed to balance them well enough to achieve some major goals. |

Before

![ScreenClip [6]](http://www.pozorblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/ScreenClip-6.png)

After

|

Direction (Smer)For Smer the emergence of the EFSF question–an issue that like the recent debt ceiling question in the US could not easily be avoided and did itself allow a 50/50 compromise solution–provided signficant political opportunities without significant risks.

- Policy. Smer has announced its belief in the need for the EFSF, and so I will take this a policy preference on its part, though the principles for or against are less clearly embedded in the Smer program than they are in that of SaS, SNS or SDKU. The real tension within Smer, I suspect, is between the nationally-oriented group (which might have some sympathy with Sulik and Slota on this) and the internationally oriented group tied to the business community (the party’s sponsors and some of its top echelon) for whom the Euro was a strong priority and who are dependent on its success for their own reputation and prosperity. This latter group won the day on the Euro and on a few other issues and appears dominant on nation-related economic questions, whereas the other group appears to have the upper hand in the party on nation-related cultural issues. (Just a guess as it all rests ultimately in the hands of Fico).

- Voters. Polls showed Fico’s voters to be slightly less supportive of EFSF than the average citizen of Slovakia but still relatively close to the mean. The party has little to lose or gain on this from its voters, and while its decision to withhold its support from something it claimed it wanted–and then to give its support once the government had fallen–is potentially problematic in the minds of some, it is not clear that the average voter will mind or will question Fico’s claim that it was the government’s responsibility to achieve its majority before he would join in. Voters thus played a relatively small role in Smer’s decision here except to the extent that Fico sought to return to them in an election as soon as possible by encouraging rifts in the current government.

- Office. Few of the incentive arrows are so clear as this one. Smer currently has a significant lead in the polls, it seeks to return to office as soon as possible and the current coalition cannot find consensus on an issue that it cannot avoid discussing. From the beginning Smer took the position that while it had a programmatic position on the issue (vote yes) it would not act on that position unless the government did first. This can be taken either as a cynical ploy to force the government to unseat itself (which it did) or as a supra-programmatic position to allow the self-defeat of a government which Smer argued was bad for Slovakia. Regardless of the normative evaluation, Smer’s desire for office gave it a clear incentive to withhold its yes vote. And it did, until the government fell and then it had a fairly clear interest in supporting the EFSF immediately so that it would not have to deal with any of these questions should it soon find itself in government. Thus Smer gets two sets of arrows above.

- External Pressure. Smer was not without pressure from outside, particularly from the Party of European Socialists which clearly wanted its affiliate in Slovakia to vote yes on the first round. But Smer has demonstrated itself to be remarkably independent of its European party home, and if the party could resist PES pressure to change coalition partners, it could certainly resist the pressure here. That PES relented on the coalition issue and readmitted Smer with no change on Smer’s part can hardly have strengthened its hand here.

Smer in opposition has been dealt an excellent series of hands and has played them quite well. At its upper levels It has developed into a well-organized and well-managed organization that knows how to take advantage of opportunities. But though Fico seems healthier and more comfortable in the role of main opponent than of the lead executive, he and his party cannot resist pressure that pushes it toward the power and position that can only be achieved in government. At present, it looks as if this is where the party is headed, though it must be noted that its high levels of support have a tendency to ebb when voters are faced with an actual choice in the polling place (or perhaps more significantly, with the choice to go out and enter the polling place).

|

|

|

![ScreenClip [3]](http://www.pozorblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/ScreenClip-3.png)

![ScreenClip [4]](http://www.pozorblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/ScreenClip-4.png)

![ScreenClip [5]](http://www.pozorblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/ScreenClip-5.png)

![ScreenClip [2]](http://www.pozorblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/ScreenClip-2.png)

![ScreenClip [6]](http://www.pozorblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/ScreenClip-6.png)