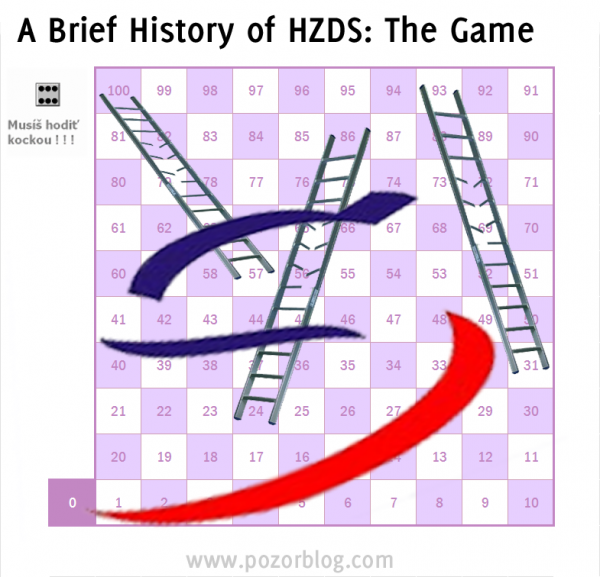

I’m rather proud of the graph I did in 2006 that traced the trendline of HZDS representation in parliament and extended it to 2010…where it crossed the X-axis precisely around June. I can’t exactly do the same thing this year since extrapolating it t0 2014 out puts HZDS at negative fifteen seats. But as I was looking at the party’s website the other day I noticed something about its logo that I have never seen before, resemblance to a game I played avidly as a child and one that in the right circumstances, fits perfectly the fortunes of this party. Do children in Slovakia play Chutes and Ladders or Snakes and Ladders, as my UK colleagues call it–or would if we ever had occasion to talk about it (Kĺzačky/Hady a rebríky)? If they don’t, they should start now with this version:

I’m rather proud of the graph I did in 2006 that traced the trendline of HZDS representation in parliament and extended it to 2010…where it crossed the X-axis precisely around June. I can’t exactly do the same thing this year since extrapolating it t0 2014 out puts HZDS at negative fifteen seats. But as I was looking at the party’s website the other day I noticed something about its logo that I have never seen before, resemblance to a game I played avidly as a child and one that in the right circumstances, fits perfectly the fortunes of this party. Do children in Slovakia play Chutes and Ladders or Snakes and Ladders, as my UK colleagues call it–or would if we ever had occasion to talk about it (Kĺzačky/Hady a rebríky)? If they don’t, they should start now with this version:

Category: political science

Polls, Parties and Politics, Part 7: How (not) to help voters translate preferences into votes

Poznamka: Vitajte! Prepac, ze vsetko tu je len po anglicky ale 1) moja slovencina je bohuzial slaba a 2) mnohe z mojich citatelov nehovoria po slovensky. Prepac. Mam, vsak, “google translate buttons” na pravej strane (bohuzial grafy a tabulky su len po anglicky. Ak chcete preklad, daj vediet: pozorblog@gmail.com alebo nechaj “comment”).

Poznamka II: HN uz publikoval slovensky preklad (neviem kto to robil, ale dakujem): http://hnonline.sk/slovensko/c1-43853830-kovac-junior-sa-uniesol-sam-volim-hzds

In recent years thanks to interactive web technologies, a variety of news outlets, civic groups and party organizations have begun to create online tests to help voters figure out the relationship between what they want and the party that most closely fits their ideological preferences (for example http://www.quizrocket.com/who-should-i-vote in the US, http://www.selectsmart.com/FREE/select.php?client=GLAR in the UK, and most recently and impressively, http://www.euprofiler.eu/). This trend has finally made it to Slovakia in the form of “Voličomer“, Pravda’s voting test which asks “How will people with similar opinions to yours vote? The same, similar or completely different? Fill out this questionnaire and you will find out right away.”

In recent years thanks to interactive web technologies, a variety of news outlets, civic groups and party organizations have begun to create online tests to help voters figure out the relationship between what they want and the party that most closely fits their ideological preferences (for example http://www.quizrocket.com/who-should-i-vote in the US, http://www.selectsmart.com/FREE/select.php?client=GLAR in the UK, and most recently and impressively, http://www.euprofiler.eu/). This trend has finally made it to Slovakia in the form of “Voličomer“, Pravda’s voting test which asks “How will people with similar opinions to yours vote? The same, similar or completely different? Fill out this questionnaire and you will find out right away.”

What I found out right away is that Voličomer leaves rather a lot to be desired:

-

The first time that I filled out the survey, I tried to exhibit the profile of a European social democrat, the party family closest to my own: moderately statist on economic questions and liberal on cultural questions. What came up first on the list, however was the Communist Party followed by the tiny HZDS-splinter AZEN, though with with a variety of other left wing parties nearby including Smer. I was willing to accept this result as reflective of the absence of cultural liberalism from most left wing parties in Slovakia (though I have a hard time believing that the KSS is the closest alternative).

The first time that I filled out the survey, I tried to exhibit the profile of a European social democrat, the party family closest to my own: moderately statist on economic questions and liberal on cultural questions. What came up first on the list, however was the Communist Party followed by the tiny HZDS-splinter AZEN, though with with a variety of other left wing parties nearby including Smer. I was willing to accept this result as reflective of the absence of cultural liberalism from most left wing parties in Slovakia (though I have a hard time believing that the KSS is the closest alternative).

- I then tried to fill out the survey as a supporter of Slovakia’s opposition. Here the results were rather good, with SaS coming first and SDKU coming second on the list, though oddly with AZEN again appearing near the top of the list.

- My next effort was to to represent a member of one of the Slovak national parties, with criticism of both Hungarians and Roma and mixed answers on economic questions that are less important for such voters. The result was below. As with my social democratic effort, an extreme party popped up first–the radically xenophobic NS–followed by Meciar’s HZDS and the Slovak National Party. But in between HZDS and SNS appeared the Party of the Hungarian Coalition, MKP-SMK! It is virtually impossible for me to think of any meaningful quiz in which these parties appear next to one another except on in which the adjectives “Slovak” and “Hungarian” are erased and respondents are simply asked about the intensity of their national feeling (which would be an interesting exercise but it is not what Pravda is trying to do with Volicomer).

- A second attempt to represent a supporter of a Hungarian party produced an equally odd pattern that included, in the top five, two HZDS splinter parties (ND and AZEN), the Christian Democrats (KDH), the Party of the Hungarian Coalition (MKP-SMK)–but not until third place–followed in short order by an obscure worker’s party (ZRS), Smer, the Roma party and the radically anti-Roma NS.

The problem here is that Volicomer does not seem to be set up in a way that could produce a meaningful answer except in certain circumstances or by accident. Setting aside the fact that like almost all such tests Volicomer is based only on policy questions and not on relevant circumstances such as who respondents voted for in the past or their affection for individual politicians, its failure to identify party preference has more a fundamental cause in its failure to deal with the linked questions of underlying issue dimensions and their salience.

Issue Dimensions

Voters’ answers to political questions tend to form a limited number of reasonably well-defined clusters, (in which case an individual’s answers each of the questions is, theoretically, fairly closely related to the answers o the others). The content of these clusters varies from country to country and from one decade to the next, though most countries have long-lasting oppositions between pro-market and pro-state clusters on economic questions and many have similar clusters on cultural and religious questions, questions of foreign policy, regional and language policy and other sets of issues (for far too much detail on this question, see http://www.la.wayne.edu/polisci/kdk/papers/cleavage.pdf). In some countries all the major political questions are more or less reducible to a single cluster, so that we can speak of one-dimensional political competition. In most, however, knowing voters’ or a parties’ position on one did not help guess positions on the others, producing two or three relatively independent dimensions. (One of the core messages in my own courses on American politics is that despite our obsession with the all-out war between “liberal” and “conservative,” there are at least two dimensions in American politics: one economic and the other cultural. For far to much detail on that question see http://www.pozorblog.com/2010/03/american-politics-in-a-nutshell/).

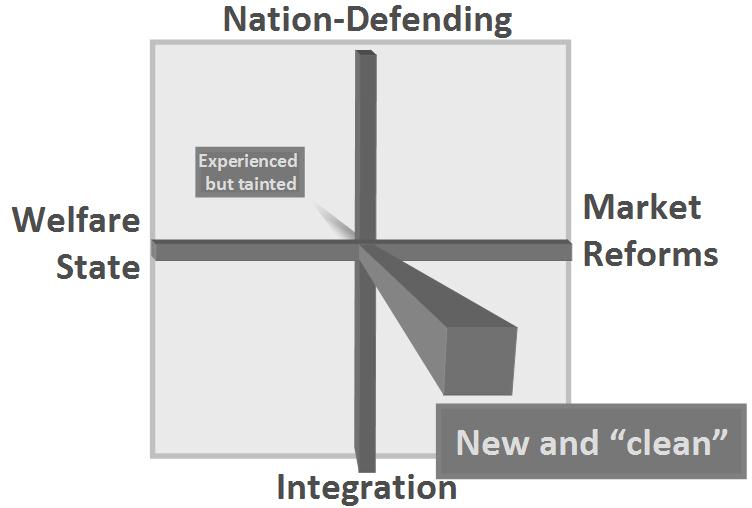

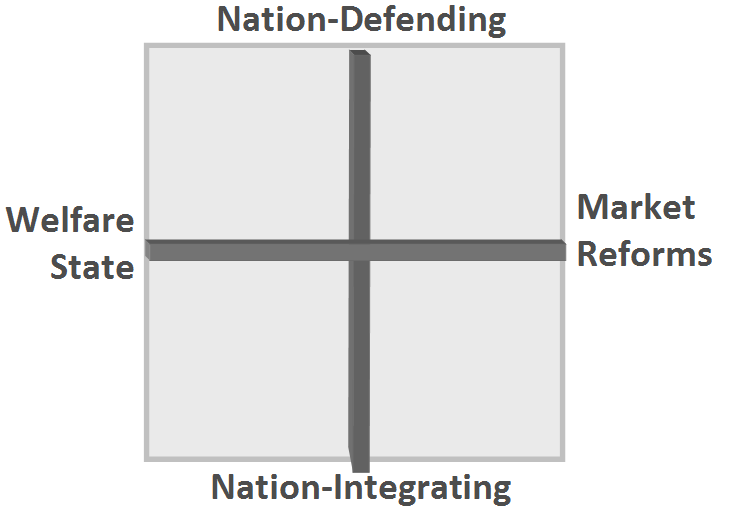

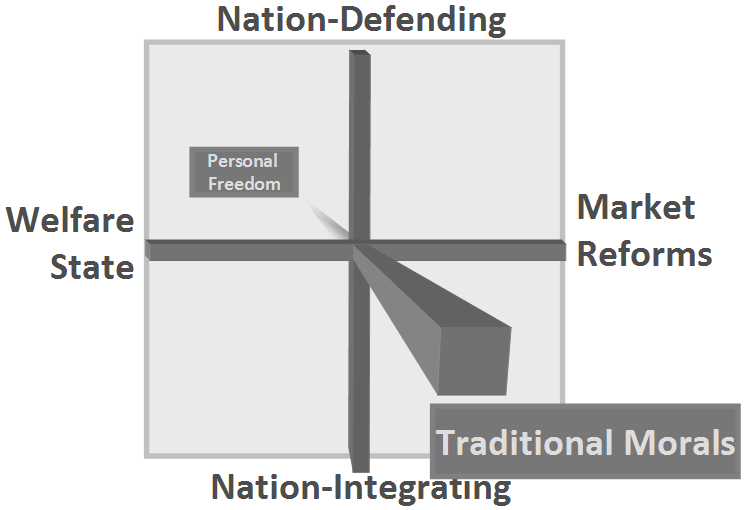

In Slovakia, I have argued, competition is at least two-dimensional. With an economic dimension and a national dimension. These have sometimes overlapped considerably but at other times have been almost completely unrelated, producing a two dimensional axis such as this graph that I’ve used in other settings:

This gets a bit complicated, of course, because “nation integrating” means, “Slovak nation defending” and its rival pole is not so much “Slovak nation integrating” as “Hungarian nation defending” but I simplify it here because the main area in which Hungarian parties and Slovak parties agree on this side of the axis is the need to integrate Slovakia into European structures. Regardless of their labels, the important question is the degree to which these axes are independent of one another or somehow aligned so that positions on one are closely related to positions on the other. This is an open question in changing circumstances.

This gets a bit complicated, of course, because “nation integrating” means, “Slovak nation defending” and its rival pole is not so much “Slovak nation integrating” as “Hungarian nation defending” but I simplify it here because the main area in which Hungarian parties and Slovak parties agree on this side of the axis is the need to integrate Slovakia into European structures. Regardless of their labels, the important question is the degree to which these axes are independent of one another or somehow aligned so that positions on one are closely related to positions on the other. This is an open question in changing circumstances.

I have some thoughts that in fact political competition in Slovakia is not defined by two dimensional but actually contains at least two additional “half” dimensions.

One of these is cultural, not in the national sense but in the religious sense and relates to issues of church and state and traditional morals. The dimension seems to be at right angles to both of the others, forcing the inclusion of a third dimension on the graph, but unlike the others two dimensions, the distribution of people and parties on this dimension is quite asymmetric, with a relatively small share on the side of the church and traditional moral and the bulk of the population and the party system on the other side.

One of these is cultural, not in the national sense but in the religious sense and relates to issues of church and state and traditional morals. The dimension seems to be at right angles to both of the others, forcing the inclusion of a third dimension on the graph, but unlike the others two dimensions, the distribution of people and parties on this dimension is quite asymmetric, with a relatively small share on the side of the church and traditional moral and the bulk of the population and the party system on the other side.

A second half-dimension, more speculative, is one that Tim Haughton and I have identified in Slovakia and other countries in central and eastern Europe: a “novelty” dimension. We have argued that there is a relatively stable (if not dominant) bloc of voters who seek less corrupt governance and who seek new, untainted parties to achieve the goal, but who are invariably disappointed when those parties themselves become corrupt. Thus although the dimension remains stable, the players on the “New and ‘clean'” pole are constantly changing. Parties such as ZRS (1994), SOP (1998), ANO and Smer (2002), SF (2006) and today’s SaS and Most-Hid have at their peak occupied the “new and ‘clean'” end of this axis but slip gradually to the other end and, with the notable exception of Smer, which found other issues on which to build its base, disappear from political competition.

Which brings us back to the Volicomer question. It is virtually impossible to understand the role of programmatic issues for party choice without a clear understanding of how those issues cluster together, how many clusters there actually are and how they are related to one another. Except in certain circumstances, a simple additive list will ultimately produce gibberish (as Volicomer does on anything other than the economic dimension where the plurality of its questions are concentrated), while the best political quizzes begin with the question of dimensionality (see Idealog, http://www.idealog.org/, and Political Compass, http://www.politicalcompass.org/).

Salience

Even a quiz designed to account for Slovakia’s two-and-two-halves dimensions of competition will not produce particularly meaningful results unless it also accounts for the salience of the issue clusters. All parties and voters emphasis that parties and voters place on them clusters when making their political decisions and these are not the same form party to party or from voter to voter. In Slovakia in particular, those who tend to care about national questions put relatively little emphasis on other clusters of issues while those interested in economics usually put national questions in the background. Knowing a person’s positions on issue dimensions, therefore, is important only if you know which of the dimensions is most important for that person. By asking a high number of economic questions, Volicomer privileges the economic dimension and therefore produces acceptable, if not particularly useful results on that dimension while failing to produce anything meaningful on issues that are restricted to one or two questions.

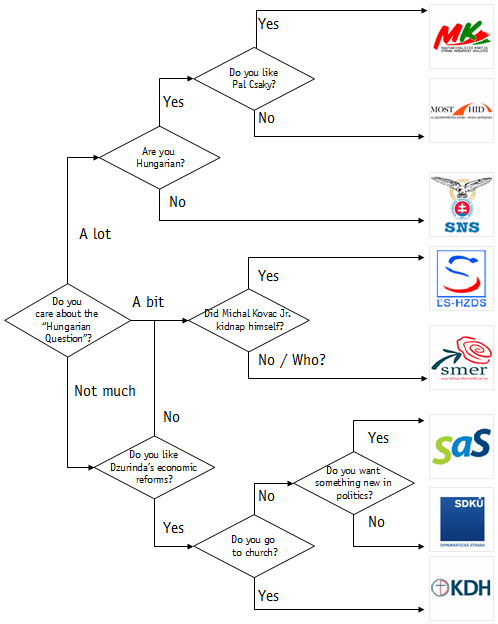

Volicomer2: A (not so) Facetious Alternative

But things like Volicomer are hard to do, you might argue, and I should accept it as better than nothing unless I am willing to do the work to provide a better option. Challenge accepted. In the spirit of the old television game show “Name that Tune” (which I have never actually seen but which was part of the pop culture of my upbringing), “I can name that party in 4 notes.” The flowchart below is a not-so-serious (but not entirely frivolous) attempt to integrate issue dimensions and salience to reduce the number of questions necessary for picking the major parties (and for the smaller parties the choice is largely random in any case):

Even a cursory look at the flowchart reveals the assumptions that I use when approaching Slovakia’s politics:

- The “National Question” is the most polarizing and those who care about national issues are unlikely to care about much else.

- The “National Question” is largely distinct from the economic questions, though those who care a little bit about national questions are more likely to prefer a statist economic policy (hence the “a bit” option that points to the choice between Smer and HZDS. This was not always the case but the two axes have slowly come into closer alignment).

- The choice between MKP-SMK is largely a personality driven one and therefore largely unpredictable on other bases.

- The choice between SDKU, KDH, and SaS is one based on religiosity in the first case and novelty/”cleanliness” on the other. In other words the two half-dimensions currently function primarily within the right wing of the political spectrum. My guess is that by the next elections there will also be a “new party” alternative within the left wing that will siphon some votes from Smer, but we will have to wait to see about that.

I’m not convinced I’m right about any of this, so I’d encourage everybody who reads this to try Volicomer, try the quiz above and see which works better. On this, as with everything, I’d love to see a larger number of reader comments!

New publication: How much difference do parties really make?

To watch American television news coverage of political questions (something I can no longer bring myself to do) or even to read American newspapers (only slightly less painful) is to learn that leaders matter. Whether a policy succeeds or fails, whether a candidate wins or loses depends on tactical decisions, on turns of phrase, on the right color tie. To read some America scholarly work on the subject is to learn the opposite: economic conditions, cultural values and demographic trends shape outcomes so strongly that you can set up an accurate electoral model before you even know who the candidates are.

As usually happens (but not always) happens, the answer is usually somewhere in between. But where depends on a whole variety of circumstances. Toward that end I have been working with Zsolt Enyedi to think about how and when agency by parties and candidates can overcome the inertia of structures that include habit, cultural values and group identities. The main outcome of the first stage of our efforts is a still forthcoming issue of West European Politics and a Routledge edited volume on the structure of political competition in Western Europe that includes a long article that Zsolt and I wrote on the topic, but in advance of that volume the European Union Democracy Observatory has been kind enough to print a slightly earlier version as a Working Paper. The paper is available here where it appears alongside work by Marina Popescu and Gabor Toka, Peter Mair and Alexander Trechsel.

Below you can find other particulars. Zsolt and I are moving to the next step in this project and are very much interested in comments, questions, concerns and slashing criticism.

| Title: | Agency and the Structure of Party Competition: Alignment, Stability and the Role of Political Elites |

| Authors: | DEEGAN-KRAUSE, Kevin ENYEDI, Zsolt |

| Keywords: | political parties cleavages structure agency public opinion |

| Issue Date: | 2010 |

| Series/Report no.: | EUI RSCAS 2010/09 EUDO – European Union Democracy Observatory |

| Abstract: | The study of cleavages focuses primarily on constraints imposed by socio-demographic factors. While scholars have not ignored the agency of political elites, such scholarship remains fragmented among sub-fields and lacks a coherent conceptual framework. This article explores both temporal stability and positional alignments linking vote choice with socio-demographic characteristics, values and group identity to distinguish among particular kinds of structural constraints. On the basis of those distinctions, it identifies various methods by which elites reshape structures, and it links those to a broader framework that allows more comprehensive research connecting political agents and structural constraints in the electoral realm. |

| URI: | http://hdl.handle.net/1814/13133 |

| ISSN: | 1028-3625 |

| Appears in Collections: | RSCAS Working Papers |

Minority minorities and the majority (or “party like it’s 1995″)

Today’s SME reports “Ministry: Representatives of minorities supported amendment on the state language (http://www.sme.sk/c/4994369/ministerstvo-predstavitelia-mensin-podporili-novelu-o-statnom-jazyku.html). We learn in the article that:

Today’s SME reports “Ministry: Representatives of minorities supported amendment on the state language (http://www.sme.sk/c/4994369/ministerstvo-predstavitelia-mensin-podporili-novelu-o-statnom-jazyku.html). We learn in the article that:

Predstavitelia chorvátskej, rusínskej, nemeckej, bulharskej, poľskej a ruskej menšiny na dnešnom zasadnutí Rady vlády SR pre národnostné menšiny a etnické skupiny vyjadrili podporné stanovisko k prijatej novele zákona o štátnom jazyku.

Which translates roughly as:

Representatives of the Croatian, Rusyn, German, Bulgarian, Polish and Russian minorities in today’s meeting of Slovakia’s Government Council for national minorities and ethnic groups expressed a supportive position to the passage of amendments to the law on state languages.

Without wishing to pass direct judgment on this story, I want simply to note that it is strikingly reminiscent of the efforts of Meciar’s Movement for a Democratic Slovakia to justify its own language law (and all of its other nationality-related policies) in the mid-1990’s. The argument is a rather clever one: most nationalities do not mind the law, so why should the Hungarians (and sometimes Roma). We love minorities (we even have a council for them) and minorities love us (they support the law), so Hungarians’ refusal to support this policy is a sign that they do not play by the same rules.

What the argument omits, of course, is that while from a technical standpoint, Hungarians (and Roma) are minorities when compared to the majority Slovak population, not all minorities are created alike. Hungarians constitute more than 10% of Slovakia’s population and in some parts of Slovakia, they are the dominant population (something similar same can be said, though in slightly different terms, for Roma). The same cannot be said for the minorities listed above all of whom, according to the 2001 census, together total 35,868 people which is less than 0.7% of Slovakia’s population and 7% of its Hungarian population. Unlike Hungarians (and Roma), Croatians, Bulgarians, Germans, Poles and Russians do not live in communities that would lead them to expect that they could lead lives in their own language without constant translation to and from Slovak. (For Rusyns it is perhaps a bit different, but the language is close enough to Slovak that the translation is less difficult) and so the language law (and one can take a variety of views on its advantages and flaws) is not particuarly relevant. Not so for Hungarians, in particular. So knowing what Slovakia’s small minorities think about the language law is not particularly useful for making an assessment of the validity of the claims of larger minorities with what American congressional-district designers would call “majority-minority” communities.

I am curious whether this particular exercise of treating unequal things as equals (a strategy taken to its height in the US by columnist David Brooks) will go any further in Slovakia. For Meciar’s HZDS, “treating all minorities equally” (a laudible goal unless there are reasons not to) was the mechanism by which the government marginalized Hungarian claims: If a right could not be given to Rusyns or Germans, it would not be fair to give it to Hungarians. If the state couldn’t support a Croatian-language university, it certainly wouldn’t be appropriate to establish a Hungarian-language university, and so on. The HZDS government even went to the extent of publishing (with EU funds) a publication called “Nationalities News” in which identical stories appeared in Hungarian, Rusyn, German and Slovak. (That many of the stories focused on the perfidy of Hungarians, including one on the Hungarian troops that crossed the border of Slovakia during the August 21, 1968 invasion was simply to add insult to the rather significant injuries that became possible once all nationalities were regarded as equals.)

In addition to the political ramifications, all of this points at two rather significantly different understandings of the relationship between Slovaks and Hungarians. Many Slovaks hold the opinion that Slovakia belongs to them, ethnic Slovaks. It is named after them, and they are the state-forming (statotvorny) nation. Others are, if not guests (and even many with strong national views would not go that far), at least minorities, and to make distinctions among them would be inappropriate as well as politically inexpedient. At the other extreme are Hungarians who argue that Hungarians are also a state-forming nation in Slovakia and should be entitled to all the advantages of living in a country in which one constitutes a majority. (Actually, of course, there is a more extreme position that Hungarians in Slovakia should bring about their majority status by bringing the territory under the political control of Hungary. For my part, however, I have never met anyone in Slovakia who would admit espousing this position, though I’m willing to admit that without speaking Hungarian I probably wouldn’t be likely to meet such people). It is notable, that those who claim Hungarians’ statotvorny status do not usually extend it also to Roma or Rusyns or Germans, and in that resemble their ethnic Slovak counterparts.

I will also be curious to see, as tensions rise, whether the philosophical justifications go as far as they did 14 years ago.

African Democracy Project Mozambique

In October my university will be sending a number of remarkable students and faculty members to Mozambique to watch elections in one of Africa’s vibrant democracies, and I have the great good fortune (especially great in light the distinct absence of references to Mozambique in my professional work) to help coordinate the trip.

In October my university will be sending a number of remarkable students and faculty members to Mozambique to watch elections in one of Africa’s vibrant democracies, and I have the great good fortune (especially great in light the distinct absence of references to Mozambique in my professional work) to help coordinate the trip.

Aside from the excitement of travel and learning something very new, I am also geeked about some new software tools, mashups, fixes and workarounds for active, project-based learning as pioneered by the remarkable Michael Wesch of Kansas State. His digital ethnography course is a model for what upper level undergraduate education can do, and so I can do no better than follow his lead. As a result, our course will be us a netvibes page to link all of the various streams of effort which I hope will include multiple blogs, social bookmarking, video uploads and whatever else we can imagine. Remarkable tools are available and it has taken only one afternoon to get them in shape for our course and cobble them together (all the same tools are probably hidden somewhere in Blackboard along with a corkscrew, a nail file and a jar of mayonaise, but Blackboard is the equivalent of Terry Gilliam’s “27B-6” though “Brazil” is not the former Portugese colony I have in mind).

For those who are interested, the key elements of the project will come together at http://www.netvibes.com/adpm and we will be using the tags “adpm” and “adpm09” to label what we find across the web.

New Parties: SaS does the electoral math

Interesting post today from Richard Sulik, founder of Sloboda a Solidarita (trendily-colored logo is at left, found not on a party website but on a Facebook page), who responds to the charge from SDKU that SaS hurt the right by causing voters to “waste” votes on a party that did not make it over the threshold (http://richardsulik.blog.sme.sk/c/196401/SaS-oslabila-pravicu.html).

Interesting post today from Richard Sulik, founder of Sloboda a Solidarita (trendily-colored logo is at left, found not on a party website but on a Facebook page), who responds to the charge from SDKU that SaS hurt the right by causing voters to “waste” votes on a party that did not make it over the threshold (http://richardsulik.blog.sme.sk/c/196401/SaS-oslabila-pravicu.html).

Sulik makes interesting arguments to suggest that SaS voters had good reason to vote in other ways and that they might not have voted at all, but he also makes good use of electoral math to make his point: he uses the electoral formula to show that reallocation of all SaS to SDKU would only have reallocated the number of seats that went to the right (SDKU would have gained one but KDH would have lost one) and thus that SaS did not impact the final result. The math looks solid to me and it is nice to see someone respond to arguments by looking at actual numbers and rules.

Nevertheless, it is not as easy to dismiss the SDKU arguments if they are seen as a warning about future elections. SaS did not have much impact in the European Parliament elections because there were so few seats at stake (13 [Correction, thanks reader “Richard”). Had it been a parliamentary election (and yes, many other things would have been different as well), Sulik’s argument is not quite as strong. I’ve reworked his numbers assuming the 150 seats of Slovakia’s parliament at stake. According to this, calcuation, SaS would have had a significant impact on SDKU votes (which would have gained 6 seats had it received all of the SaS votes) which is partially but not completely ameliorated by its impact on KDH and SMK (each of which would have lost a seat). In terms of coalition and opposition, this is almost a crucial difference: from clear parliamentary majority for Smer-SNS-HZDS to a bare majority that would hinge on the decision of only two deputies.

European Parliament Election Results if 150 seats (the Slovak Parliament) were available for election, according to two hypotheses:

| Party | SaS supporters vote for SaS | SaS supporters vote for SDKU |

| Smer | 56 | 53 |

| SDKU | 30 | 36 |

| SMK | 20 | 19 |

| KDH | 19 | 18 |

| HZDS | 16 | 15 |

| SNS | 9 | 9 |

| Smer+HZDS+SNS | 81 | 77 |

| SDKU+SMK+KDH | 69 | 73 |

Of course this is all theory, but the underlying debate is deeply relevant. The more the fragmentation on the right, the worse it is likely to do (as the left and the Slovak nationals demonstrated in 2002), but it is not a zero-sum game and it may be true that Sulik’s party brings out new voters. His ability to mobilize certainly is apparent in this election. The question for me is whether the best use of Facebook/youtube/social networks is enough to attract the 115,000 voters who will likely be necessary to get a party over the 5% threshold in 2010? The effort is certainly worth watching.

Euroblindness

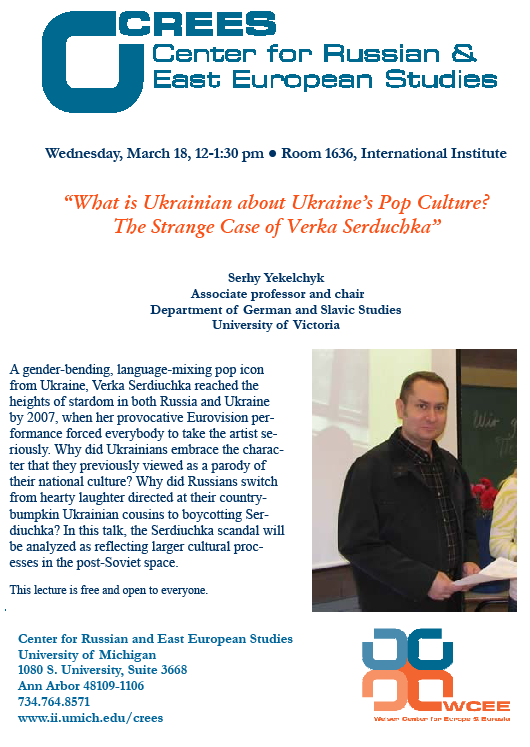

It is nice to see that my rather painful obsession with the Eurovision Song Contest (other people’s tragedies are always more palatable) has some relevance for my profession:

Nice to see, too, that Slovakia will finally have an entry so that I can see who likes the Slovaks (and watch the excitement as Slovakia’s Hungarian minority votes the whole country’s 12 points for the Hungarian entry (on the odd chance that the Hungarian makes it to the final round): http://www.eurovision.tv/page/news?id=1989

Elected Affinities in the Cloud

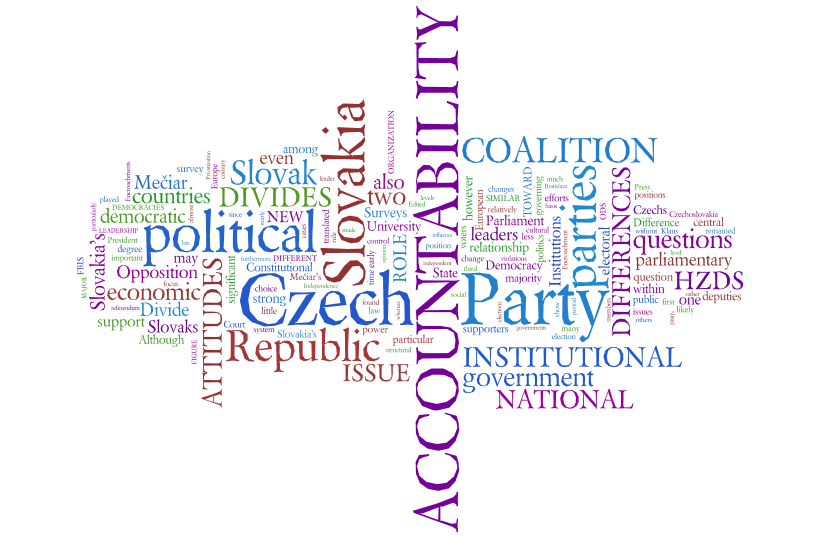

The first blog I ever read on a regular basis was BldgBlog and I still read every word, so when it posted a word cloud of the upcoming BldgBlog book made on wordle.net , I felt obliged to try it with my own book. The results are gratifying:

Not only does it look a bit like Slovakia and/or the Czech Republic, but it really does contain all the ideas I cared about when I was writing it (and care about still). And it helps me think about the idea of machine-based content analysis. While this counting words does not say much about what I think, it does accurately capture what I am thinking about. (See here for other ways to determine what I am thinking about; see below for wordles with different font and color schemes).

Poll Analysis: UVVM Volatility

Also available in Slovak, here

I have occasionally expressed concern about the recent numbers coming out of UVVM, particularly those for the Party of the Hungarian Coalition. Something is wrong there. In the spirit of my heroes at http://www.fivethirtyeight.com, I decided to take a look at the data. The chart below calculates the total month-to-month differences in party results (up, or down) and then measures these as a percentage of a party’s average support during that period (i.e. a party with an average support of 20 percentage points and average monthly volatility of 1 percentage points would be listed at 5%). I have done the calculations for the overall average (all of the polls within a given month) and for UVVM and for the two electoral periods for which we have good data: 2002-2006 and 2006-present.

| Party | 2002-2006 | 2006-2008 | ||||

| Overall | UVVM | Difference | Overall | UVVM | Difference | |

| Smer | 7.0% | 9.2% | 2.2% | 8.9% | 7.8% | -1.1% |

| SDKU | 12.5% | 16.4% | 3.8% | 13.2% | 16.2% | 3.1% |

| SNS | 14.7% | 18% | 3.3% | 12.1% | 12.1% | 0.0% |

| MK | 8.0% | 12.0% | 4.0% | 10.1% | 16.1% | 6.0% |

| HZDS | 9.9% | 12.4% | 2.5% | 12.2% | 14.1% | 2.0% |

| KDH | 10.4% | 16.1% | 5.8% | 10.2% | 10.9% | 0.7% |

| Average | 10.4% | 14% | 3.6% | 11.1% | 12.9% | 1.8% |

What is not surprising here is that UVVM alone has much higher levels of volatility than the overall average which includes multiple polls that smooth out the monthly variability. What is surprising here is the fact that the the difference in volatility of SMK between UVVM and the overall average grew (from 4% to 6%) even as the differences between UVVM and other surveys declined. Between 2002 and 2006 the volatility of SMK was second to the bottom (after Smer) in both UVVM and overall averages. Between 2006 and 2008, the SMK volatility stayed the second lowest in the overall averages but rose to highest in UVVM by a wide margin.

This is all particularly surprising since the overall volatility of the Hungarian Coalition’s electorate have remained remarkably stable over time, as the following table demonstrates:

| Party (elections in sample) | Volatility as a share of average party support | Raw volatility |

| ANO (2002,2006) | 103.2% | 4.9% |

| SNS (1994,1998,2002,2006) | 80.5% | 5.9% |

| Smer (2002,2006) | 73.6% | 15.7% |

| KSS (1994,1998,2002,2006) | 51.2% | 2% |

| SDKU (2002,2006) | 45.1% | 7.5% |

| HZDS (1994,1998,2002,2006) | 38.7% | 8.7% |

| MK (1994,1998,2002,2006) | 11.4% | 1.2% |

| KDH (1994,2002,2006) | 10.7% | 0.9% |

There is an easy explanation for this: UVVM has had difficulty maintaining its Hungarian sample. This is understandable–this is a difficult task–but it is important to keep this potential problem in mind rather than to assume that all polls actually reflect representative samples. This should be a question of analysis rather than assumption. It also raises questions about the representativeness of this sample (and that of other pollsters) for other parties.

I am deeply grateful to UVVM for all the support they have provided to me over time. This is a problem that needs attention but I am hopeful that the institute can return to its previous levels of excellence.

Not To Minsk Words

I returned two days ago from Belarus where I was an observer in the 2008 parliamentary elections.

OSCE rules request that we leave assessments to the organization’s main report and remain silent. Fortunately, in this instance, the OSCE judgement so closely corresponds to my own experience that I can refrain from my own judgments and express my own empressions exclusively through quotations from the initial report. That report can be found online at http://www.osce.org/item/33272.html. Unless otherwise noted, the quotations reflect my own personal experience.

The Scope Of The Mission:

As OSCE notes, “On Election Day, 449 observers were deployed to observe the opening of polling stations, the process of voting, the vote count, and the tabulation of the votes at DECs. This included 76 specially designated teams to observe the tabulation process.”

What Went Relatively Well: The Voting Process

The OSCE report perfectly mirrors my own experience regarding the experience of voters in the voting process:

- “On election day, observers reported that voting was well conducted overall in those polling stations visited.”

- “Observers generally evaluated the opening procedures as good or very good in 100 per cent of the 93 cases observed.”

- “The voting procedures were also positively assessed by observers, with 95.4 per cent of cases evaluated as good or very good.”

With a relatively minor exception:

- “Campaign materials were displayed inside polling stations in 3 per cent of cases.”

What Did Not Go Quite As Badly: The District Election Commission Process

Again, the OSCE report mirrors my own experience regarding the conduct of the aggregation of the count at the district level:

- “While some opposition candidates claimed to have been the subject of pressure on the part of local administrations, other candidates, including from the opposition, declared that the attitude of DECs was friendlier and more open than in the past and that the pre-election climate was improved.”

Nevertheless, as the OSCE reports,

- “In 54 per cent of tabulations observed, they were not able to observe the figures being entered into the spreadsheet tables.”

What Went Badly: The Counting Process

As the OSCE report concludes, “Voting was generally well conducted, but the process deteriorated considerably during the vote count. Promises to ensure transparency of the vote count were not implemented….” The process deteriorated considerably during the count and tabulation, violating paragraph 7.4 of the Copenhagen commitments of the OSCE.

- “The integrity of the process was undermined by the vote count which was assessed by observers as bad or very bad in 48 per cent of observations [including me]. “

- “37 per cent of observers, including some of those who noted hindrances [i.e. including me], reported not having a full view of the vote count proceeding, thus compromising the transparency of this fundamental element of the election process.”

- “OSCE monitors were prevented or hindered from observing the vote count in 35 per cent of cases. This compromised the transparency of this fundamental element of the election process.”

- “In 50 per cent of cases, early votes were not compared with the number of entries in the voter lists.”

- “Observers could not see the voters’ mark in 53 per cent of cases.

- “Numerous cases were noted of counting procedures taking place in complete silence with small slips of paper being passed between commission members; this significantly undermined any transparency in the count.”

Reading Between the Lines:

What to make of an election that combines relatively smooth voting and district-level counting with comprised transparency at the polling-station counting stage? The OSCE report makes certain suggestions about the possible reasons. These conform to my own experience.

- “From observers comments, in some instances it was noted that there were significant discrepancies between turnout observed and the number of votes noted in PEC protocols…. A high incidence of mobile voting was noted in some cases.”

- “Where access was possible, several cases of deliberate falsification of results were observed…. Deliberate falsification was observed in 5 cases by observers.

If, indeed, the non-transparent counting procedures reflect discrepancies, this requires an explanation of how the aforementioned discrepancies could be combined with a relatively transparent voting process. The OSCE report offers several potential explanations that correspond to my own experience:

- “Lack of clear detailed regulations on the printing of ballots, the number of ballots to be printed, the percentage of extra ballots, and security features”

- “Lacking instructions on observation, each PEC was free to decide on how observation would be dealt with.”

- “The Electoral Code does not provide any clear mechanism for securely keeping the ballot boxes after the start of early voting, nor does it provide specific regulations for enhancing the integrity of the ballot.”

- “The lack of any official protocols to document the record of voting on each day of early voting remains a concern. These outstanding issues allow the possibility of electoral malfeasance.”

And, perhaps most significant of all,

- In nearly all cases in which OSCE/ODIHR EOM observers had access to such information, they reported that PECs were composed of staff from the same place of work, such as enterprises or schools. Existing hierarchical relationships seem to have been transferred to the PEC, i.e. heads or deputy heads of such work places became PEC chairpersons, with their staff as the PEC members. This further contributed to the lack of independence of individuals in the commissions…. The composition of election commissions diminished stakeholders’ confidence in the process.

Most interesting of all, is the question of why. If, as OSCE notes, “The election took place in a strictly controlled environment with a barely visible campaign,” why should engineered discrepancies and falsifications be necessary at all? The need to make minimum turnout requirements? The desire for overwhelming margins of victory? Simple habit? I will leave answers to these questions for other experts and other venues.