I thought there was not much to say about the results of the recent presidential elections in Slovakia, but I after writing the 2000 words below, I seem to have been wrong (or I have written a lot of words about nothing. Having taken a closer look at the numbers, I see in them both a confirmation of conventional wisdom—the strength of the right-wing vote, the weakness on the left-wing vote—along with often overlooked considerations about the role of political supply in addition to political demand and the pivotal role of new faces.

The Big Picture:

Fico gets some voters back, but Kiska takes the center right

After the first round, I made the (rather obvious) argument that this election would be decided by 1) the degree to which Fico the degree to which he could mobilize his own voters and simultaneously 2) could delegitimize Kiska and thereby pry center-right voters away from him, and that some combination of both would be necessary. The results of the second round suggest that his efforts fell short on both counts, but especially on the second. On the first front, Fico managed in the second round to increase his support in areas where he was already popular, suggesting that he did manage to increase turnout among his own supporters by a significant, but even among these he did not reach the mobilization levels he obtained in the (admittedly unusually pro-Smer) 2012 parliamentary election. On the second front, Fico’s efforts appear to have failed completely: evidence suggests that in the second round Kiska won nearly all of the votes of the supporters of other center-right parties in addition to his own (relatively fewer) first round voters. In a way that is not surprising since voters of the Center Right are unlikely to listen to critiques coming from the mouth of Fico.

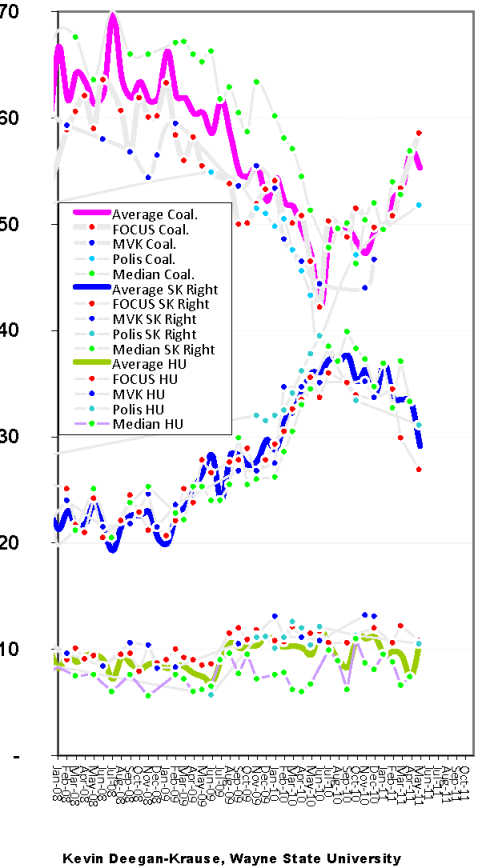

Several tables and charts provide an effective overview of the election. These are, in a way, massively oversimplified, suggesting, among other things, an undifferentiated spectrum within the center right, when in fact it ranges from strong Catholics to strong agnostics, from doctrinaire free-marketeers to those who are willing to accept a social market hybrid, and from ethnic Hungarians (whom I classify under Center Right for convenience) to ethnic Slovaks with a strong national sense. It also suggests there is /any/ connection between the ‘other’ presidential candidates from the Communist Party with those of more nationally-oriented forces, with a series of rather idiosyncratic efforts). In the case of the Center Right, there are enough similarities and historical ties of similarity that the comparison is warranted; in the case of the “others”, the number of such voters is so small as to not have great impact on the overall outcome.

| Table 1. Votes and percentages for candidates in the first and second rounds of Slovakia’s 2014 presidential election | ||||

| Raw votes (rounded to the nearest 1,000) | ||||

| 2nd round vote compared to first round vote | ||||

| Round | Change, 2nd-1st rounds | |||

| 1st | 2nd | Narrow (candidate only) | Wide (candidate and associated) | |

| Kiska | 456,000 | 1,307,000 | +851,000 | -15,000 |

| Right | 866,000 | – | – | |

| Fico | 532,000 | 894,000 | +362,000 | +316000 |

| Other | 46,000 | – | – | |

| Percentage | ||||

| 2nd round vote compared to first round vote | ||||

| Round | Change, 2nd-1st rounds | |||

| 1st | 2nd | Narrow (candidate only) | Wide (candidate and associated) | |

| Kiska | 24% | 59% | 35% | -10% |

| Right | 46% | – | – | |

| Fico | 28% | 41% | 13% | 10% |

| Other | 2% | – | – | |

Source for all tables and charts: http://prezident2014.statistics.sk/Prezident-dv/download-sk.html, and http://volby.statistics.sk/nrsr/nrsr2012/menu/indexd.jsp@lang=sk.htm

What does Table 1 show us? Assuming my a priori logic about the existence of a programmatically coherent bloc of Center Right voters (taken as a bloc the largest single group), it appears that the bloc shifted en masse to Kiska, and gave him his second round victory. Surveys (http://www.sme.sk/c/7137934/kto-su-volici-fica-kisku-a-prochazku-volebne-grafy.html) suggest that Kiska was a viable option for nearly all voters of the Center Right whereas Fico was not, and the number of voters gained by Kiska nicely matches the number of those who supported losing Center Right candidates (differing by a mere 15,000). Since we do not know who these voters are, however, such evidence is purely circumstantial unless we go deeper. What we discover is that while appearances may sometimes be deceiving, in this case they are not.

A Collage of Small Pictures:

Little pieces tell the same story

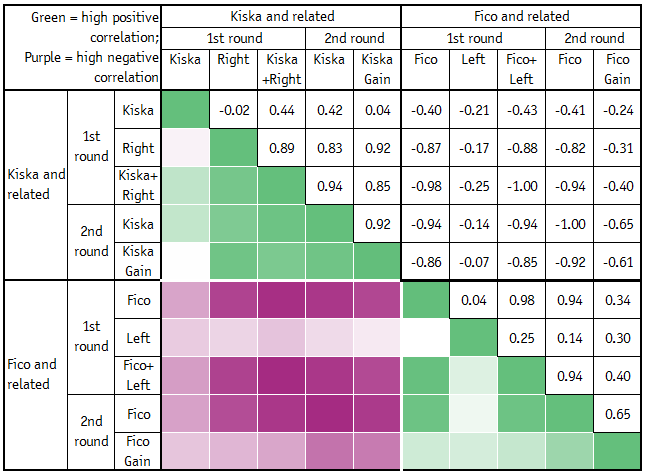

The second table shows a new set of patterns based on correlations between vote share among candidates at the municipal level. These compare patterns of performance of Kiska and the Right, Fico and the other candidates and do so across the first and second rounds.

| Table 2. Correlations between municipal-level votes in various categories in the first and second rounds of Slovakia’s 2014 presidential election. |

|

Relationship between candidate vote and potentially associated candidates in the first round:

- No relationship between the Kiska vote and the Right vote

- No relationship between the Kiska vote and the “Other” vote

Relationship between the combined vote of the candidate and associated candidates in the first round and the votes for the candidate himself in the second round

- A very strong relationship (.94) between voting for Kiska and the right in the first round and Kiska alone in the second round.

- An identically strong relationship (.94) between voting for Fico and the “other” candidates in the first round and Fico alone in the second round.

Relationship between candidate vote in the first and second rounds

- Moderate relationship for Kiska (.41) suggesting that something major affected his geographical appeal (and since his vote total rose, it suggests that it is related to the new voters)

- Strong relationship for Fico (.94) suggesting that his vote increased across the board without changing geographical patterns

Relationship between candidate vote and gain in the second round

- No relationship for Kiska (.04) suggesting that new votes came from areas outside the candidate’s initial base

- Moderate relationship for Fico (.34) suggesting that the 2nd round efforts tended (at least more than in the case of Kiska) to mobilize voters from the candidate’s base.

Relationship between “related vote” in first round and candidate gain in second round

- Extremely high for Kiska (.92) suggesting that most new voters came from the base of the right candidates (if not the same exact voters)

- Moderate for Fico (.30) suggesting that some new voters may have come from the “other” candidates but that these were drowned out by those coming from the candidate’s base.

So this gives quite direct evidence for what I already strongly suspected (and what other pollsters knew long before I did, http://spectator.sme.sk/articles/view/53464/2/ficos_voters_boosted_turnout.html): that Fico’s new voters in the second round came from newly remobilized supporters in his existing regional support bases while Kiska’s new votes came as a transfer of the already mobilized first round center right voters (Of course not all of Kiska’s vote came from previous center-right voters: some of those no doubt stayed home and some new voters no doubt turned out, but the overall pattern is remarkably strong and so they appear to have canceled each other out.)

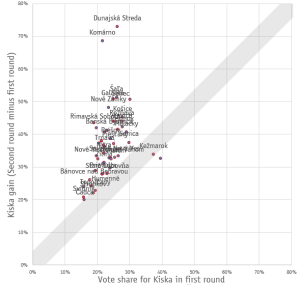

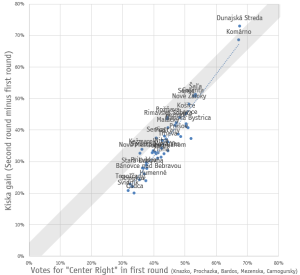

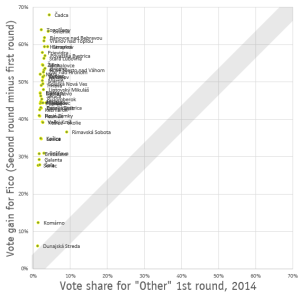

A few graphs can help make this rather concrete (I’ve decided to put the labels in even though they are mostly illegible where the cases bunch up. It’s ugly but it allows for a look at some of the outliers, mainly the Hungarian cases, but explaining those is a job for another day).

These snapshots of “obvod” (subdistrict) level voting show a strong correlation between right candidate support in round 1 and Kiska gains in round 2, but they do not show much of a relationship between Kiska’s own results in round 1 and 2 (more of a vertical distribution). The opposite pattern is apparent for Fico with a very slight contribution from “other” candidates and a strong correlation between his round 1 and 2 results. Fico drew second round voters where he had already drawn first round voters, but he drew more of them.

A Moving Picture:

Old patterns filtered by new choices

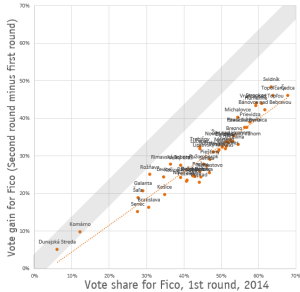

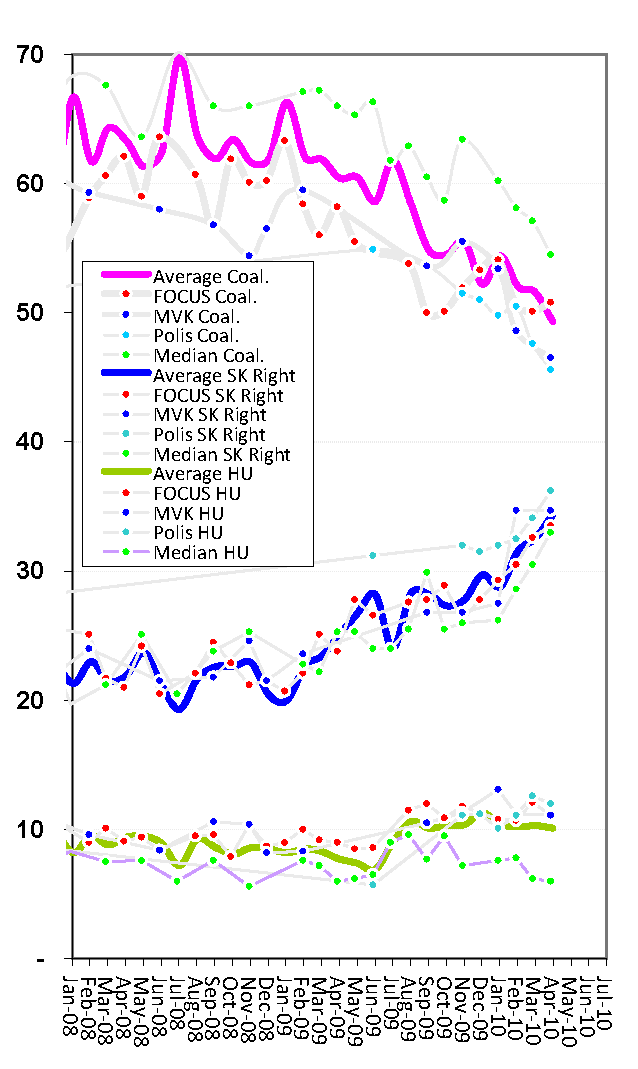

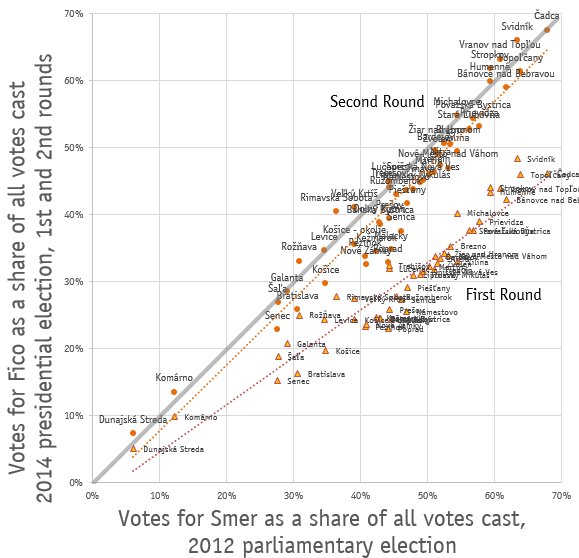

The patterns here draw attention to the ways that this election fits into the broader sweep of Slovakia’s political history. Looking at the ways in which Fico’s second-round presidential vote followed first round patterns tells us something about the stability of his support (and the lack of influx from other sources). Looking at the relationship between candidates’ 2014 performance and that of their respective parties in 2012 helps explain why the election was so (unexpectedly) lopsided. As the graph below shows, the Fico’s results in 2014 almost perfectly followed his party’s results in 2012, but they were lower, much lower.

Table 5. Fico vote share in first and second rounds compared to Smer vote share in 2012. Note that in most obvods even Fico’s second round performance falls short of the diagonal line that indicates parity with 2012.

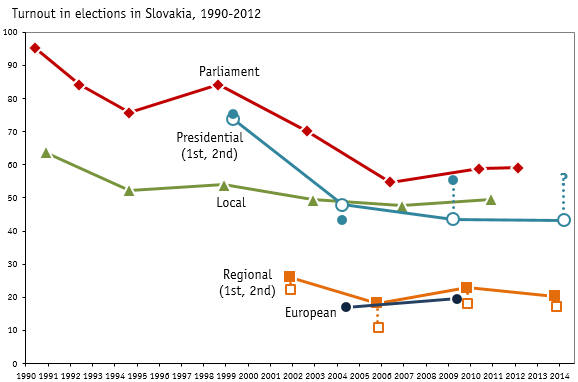

In the first round, Fico received an average of fewer 11,000 votes per sub-region. In the second round that gap dropped but Fico still turned out 5,000 fewer voters per sub-region than his party had in 2012. Of course some drop is natural since presidential elections usually have lower turnout levels than parliamentary elections in Slovakia, but it only works if your opponents also have lower turnout levels than in the past. As the third table shows, the 2014 vote did not work that way.

| Table 3. Presidential candidates’ 2014 vote totals as a share of the vote totals of their respective parties in 2012 | ||

| 2014 vote as a share of 2012 vote | ||

| First | Second | |

| Fico | 47% | 79% |

| Right | 84% | – |

| Kiska | – | 127% |

After turning out fewer than half of his 2012 voters in the first round, Fico managed to increase that in the second round to nearly 80% of his 2012 performance, but—and this may be the single most interesting statistical result of the election—the six candidates of the center right had together already achieved a mobilization level above 80% in the first round, not including votes that went to Kiska. In fact, the candidates from center-right parties attracted nearly as many votes in the first round as Fico did in his much improved performance in the second round. And when the center-right voters shifted joined with the already significant share of voters who had already opted for Kiska, Fico did not have a chance.

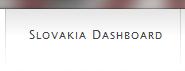

Even without Kiska in the race, Fico faced big challenges—bigger than I saw at the time. In running for president, Fico needed to outperform his own party’s parliamentary support level by something over 5% (since Smer had only managed 44.4% in the previous election), and the degree of necessary outperformance increased with every drop in Smer’s support. By early 2014, the Smer’s preference levels had dropped to the high 30%’s , requiring Fico to outperform his party by at least 12 percentage points. In the second round, Fico probably did outperform his party, but if we use the latest FOCUS polling numbers (http://www.focus-research.sk/files/168_Preferencie%20politickych%20stran_jan-feb_2014.pdf) that outperformance was probably in the neighborhood of 3% rather than 12%.

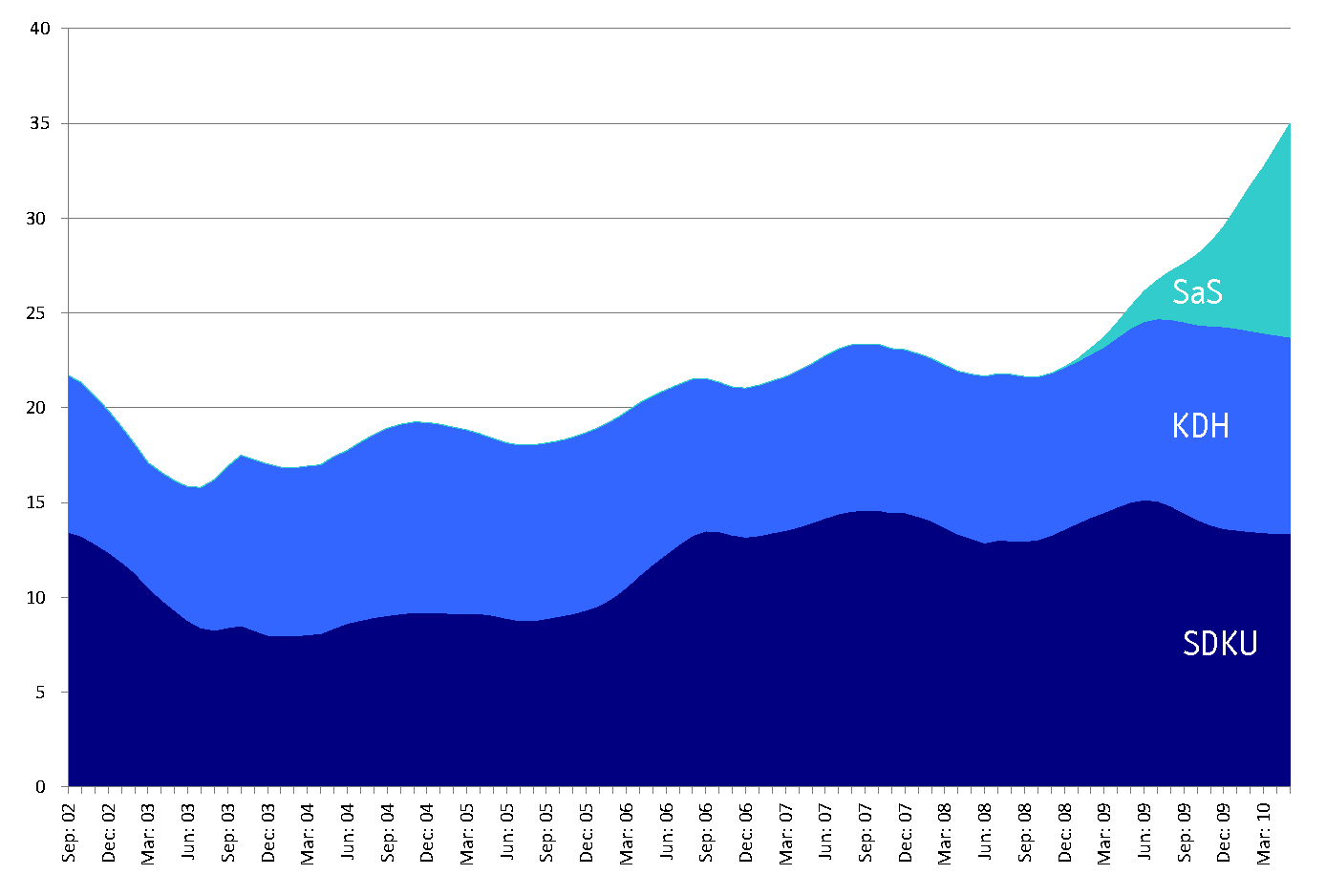

Of course elections are not about the level of preference alone but about comparative preferences. The right seems to have managed its high first-round mobilization not through skillful campaigning or inspiring candidates but through a wide degree of choice (each slightly different flavor bringing out a slightly different group of voters) and a common enemy (the prospect of Fico and his party occupying every major political institution). Had a center-right candidate gotten into the second, however, Smer could have benefitted from some of the same logic in the second round: the right could no longer provide such a high degree of choice and Smer voters would also have had a common enemy (the prospect of, say, Prochazka, occupying the presidency). This might have increased the Smer turnout above 80% and also limited the gains the center right could make in the second round, and at least produced a close election.

Instead, it would appear, the presence of Kiska in the second round gave the center right the best of both worlds: it preserved the first round center-right mobilization by offering a (marginally) acceptable candidate who could promise to stop Fico, and who could also attract voters for whom center right candidates were also anathema. At the same time, Kiska presented Smer with significant problems since, for all the claims about scientology, usury and inexperience, he was apparently not frightening enough to push Smer voters and sympathizers to the polls.

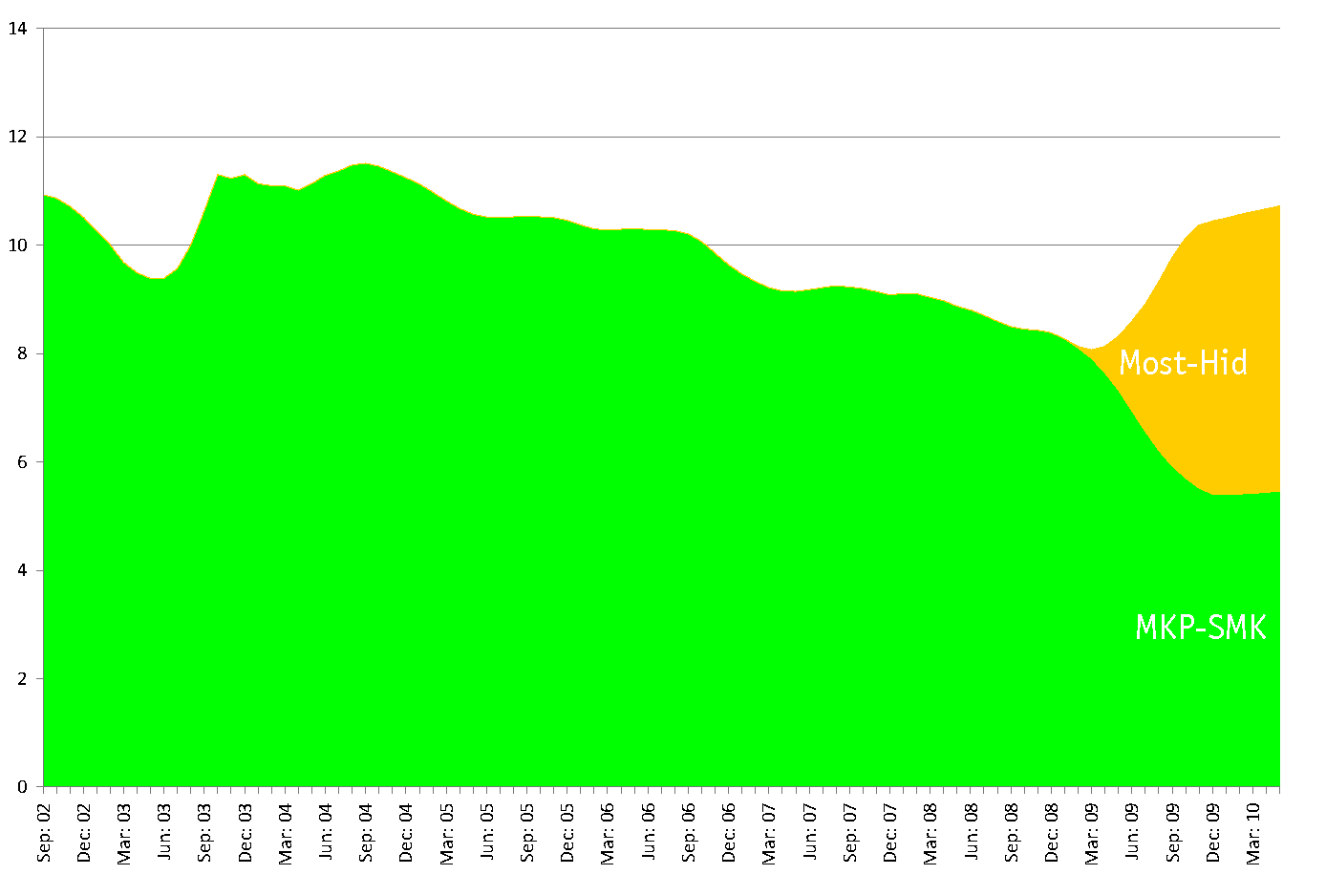

Previews of Coming Attractors?

What this election might tell us about the next one(s)

Let me finish with some half-baked speculation that deserves to be looked at with a very critical eye. For all its infighting and its poor choices—of which there are many examples—Slovakia’s center right has managed to remain a player because it has managed to retain the allegiance of the Hungarian minority and has managed to accommodate the emergence of multiple, sequential new players (SOP, ANO, SaS, OLaNO, and now Kiska) who provide outlets for dissatisfied voters whereas with the exception of the period between about 1999 and 2003, the opposite side of the political spectrum has been dominated by a single party that tries (successfully in the case of Smer, ultimately less successfully in the case of HZDS) to present itself as an unstoppable force and to prevent the emergence of rival players. The result on the right has been a surprising degree of success (1998, 2002, 2010, now Kiska in 2014) usually followed by paralysis among the multiple players whose presence in the electoral market allowed the victory in the first place. The result on the left has been political forces that win big pluralities but often lack sufficient allies to create a majority.

Toward this end, Fico’s poor performance in the 2014 presidential election may hold a certain perverse hope for Slovakia’s left. If the result of this election is to produce cracks in that party or even just to open a space in the minds of some voters (and, especially, some funders), then we might see an end to Fico’s skillful institutional monopolization of political space. If Fico and his party cannot preserve their one-party parliamentary majority, then the emergence of new parties on the center left might be able to sop up some of the dissatisfied voters who seem to have decided that Fico is just the same as all the others. Kiska, a candidate not unfriendly toward the center right picked up those pivotal floating voters in this presidential election. New center right parties such as Prochazka’s and NoVa will try to pick them up in the next parliamentary election but with varying degrees of success. Fico can hope that the center right continues its intra-familial feuds and ends up with a bunch of parties just below the threshold (not necessarily a bad bet given the past track record of the right), but by relinquishing a little control on the left and allowing a new party somewhere on that side of the spectrum might actually help him remain prime minister. (As to whether that’s what Fico actually wants, I’ve decided to stop speculating on matters that exist only in the heads of distant leaders.)