The first “first” for Slovakia is a female prime minister, a particularly noteworthy development because Slovakia has never had a particularly strong representation of women in positions of power. Slovakia differs little from its neighbors in this regard: the Visegrad Four—a regional grouping consisting of Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Poland and Hungary—has had only one other female prime minister in the last 20 years (Poland’s Hanna Suchocka in the early 1990’s) and although several of the other countries in the region have had female presidents (Latvia) or Prime Ministers (Lithuania and Bulgaria) women still remain the exception in postcommunist European politics. Indeed the incoming government of the Czech Republic may have no women at all, and despite Radicova’s control of the premiership, her own government will have only one other woman, and Slovakia’s new parliament actually has fewer female deputies than it did four years ago.

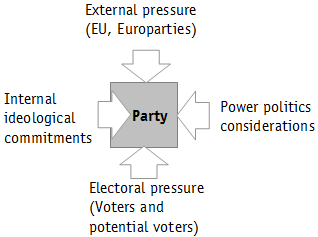

The other “first” is more subtle and involves the comparatively brief tenure of the outgoing Prime Minister, Robert Fico. In Slovakia’s first eight years of postcommunism the premiership was dominated by Vladimir Meciar, twice removed by parliament but twice returned by voters; in the next eight years, the seat was occupied without a break by Mikulas Dzurinda. By this standard, Fico is the first elected prime minister in Slovakia whom voters did not immediately reward with a second chance at government. There are several reasons why this might be so. One reason, largely outside the political realm,involves the economic difficulties faced by Slovakia’s export-dependent economy in 2009, an effect exacerbated by the tendencies of voters in postcommunist countries to punish incumbents for whatever might go wrong, a phenomenon that Andrew Roberts of Northwestern describes in terms of hyperaccountability . A more “political” explanation attributes the fall of Fico’s government to voter distaste for a long series of scandals involving government ministers. Both explanations have some purchase, but they need to be understood in the context of intra-party dynamics which I discuss in the next section. Those readers who would prefer dental surgery to a tedious discussion of Slovakia’s intra-party dynamics may skip down to the section “Why should we care” below.

How we understand Slovakia’s political shift over the last four years depends heavily on what we are looking for. Analysis tends to settle at one of three levels, all of which have some claim to the truth, provided that we understand the context.

Level one: Right coalition wins, left coalition loses

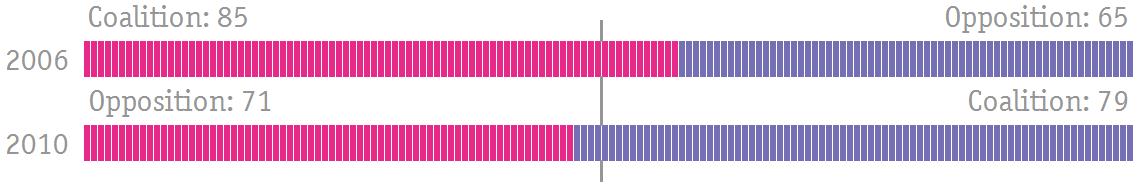

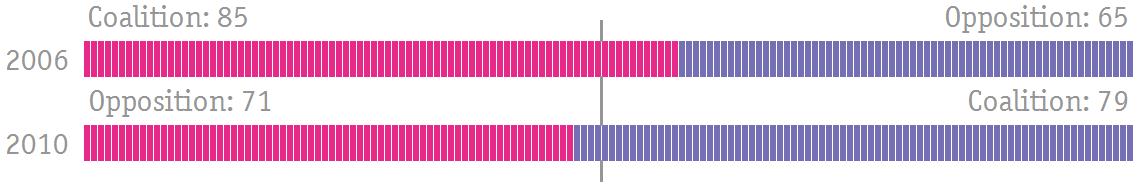

The most superficial (but not unimportant) level of analysis looks at coalitions and oppositions and involves a one-dimensional space. In this space, the 2010 elections represent the handover of power from “left” to “right” and involve a swing of 7 seats in Slovakia’s 150 seat parliament from Fico’s coalition to Radicova’s. (Fico’s coalition dropped from 85 seats in 2006 to 71 in 2010) . For the purposes of governing, this makes all the difference. But it helps to go deeper.

Dimension 1: Changes in relative coalition size. Red represents the Fico-led coalition; Blue represents the Dzurinda/Radicova-led coalition

Level two: Left and right parties gain, Slovak national parties lose

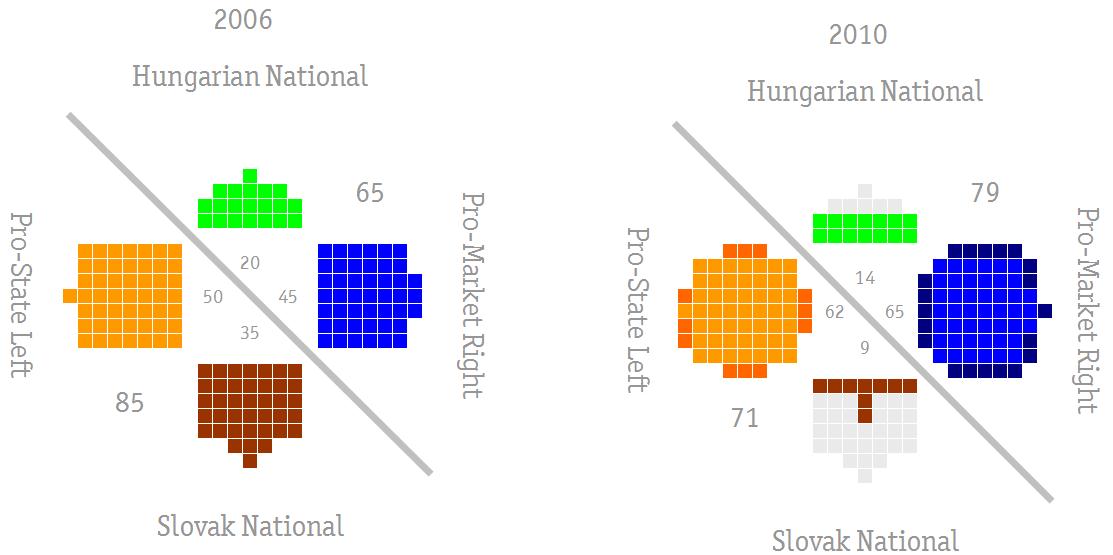

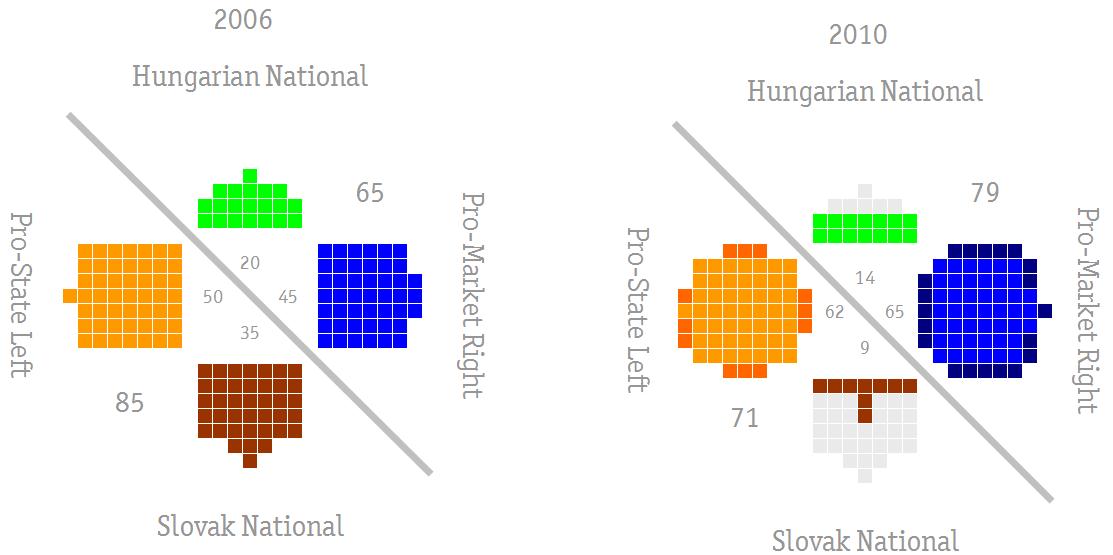

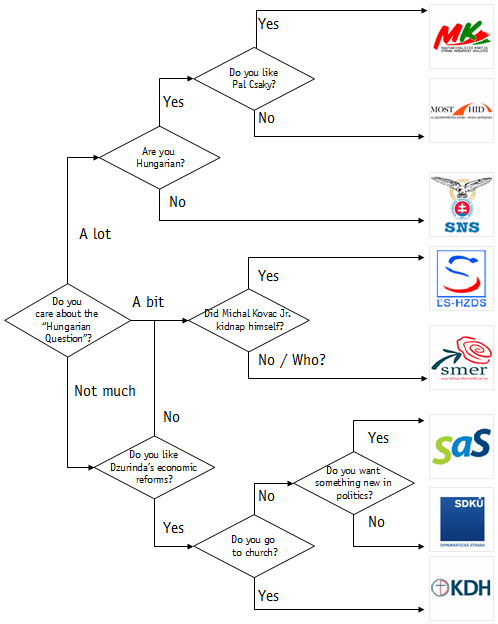

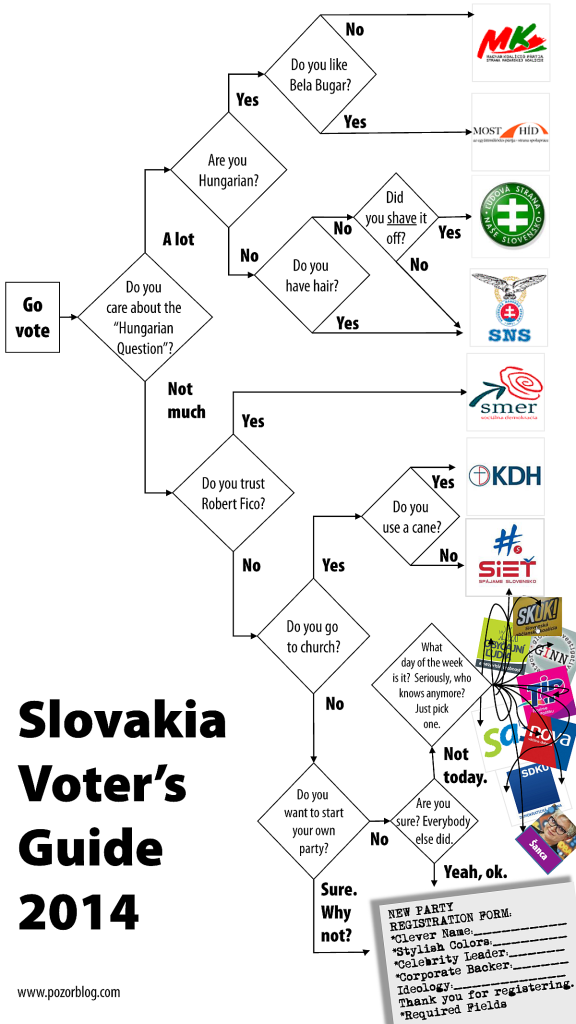

The second level of analysis looks at parties and involves a two dimensional space. In addition to the left-right axis of competition that has dominated Slovakia’s governments in the last 10 years, there is a clear competitive axis related to national questions, and two additional blocs of parties that I have labeled “Slovak national” and “Hungarian national.” According to this framework, Fico’s government represented a coalition between “anti-market left” and “Slovak national” whereas the Radicova government (like the Dzurinda government that preceded Fico before 2006) is a coalition between “pro-market right” and “Hungarian national.”

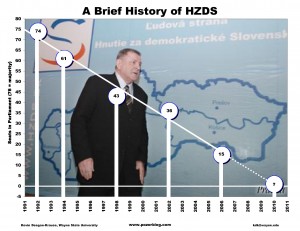

Analysis of election results according to these blocs produces a rather different set of judgments. Although the total vote share of “right” parties of the incoming government increased by five percentage points from 2006 to 2010, the vote share of the “left” party in the outgoing government—Fico’s “Direction”—increased by even more. Corresponding to the gains by both left and right were major losses in the “Slovak national” bloc: the Slovak National Party under Jan Slota fell catastrophically from 12% to 5%, squeaking over the barrier for parliamentary representation by just two thousand votes out of two-and-a-half million cast, and Vladimir Meciar, once the sun and the moon of Slovakia’s politics, continued a remarkably long gradual slide into obscurity, falling below the barrier and out of parliament altogether. Like Jaroslav Kaczynski in Poland in 2007, Fico can therefore justifiably claim not he, but his partners lost the election (though Meciar has publicly suggested that having undermined his partners to maximize his own party’s gain, Fico deserves his fate). This begs the question, however, of exactly where the “Slovak national” voters went and why.

Dimension 2: Changes in relative bloc size. 2010 figure indicates lost seats in light grey and gained seats in deeper colors.

Level three: Slovak national voters move left, anti-corruption voters move right (for now)

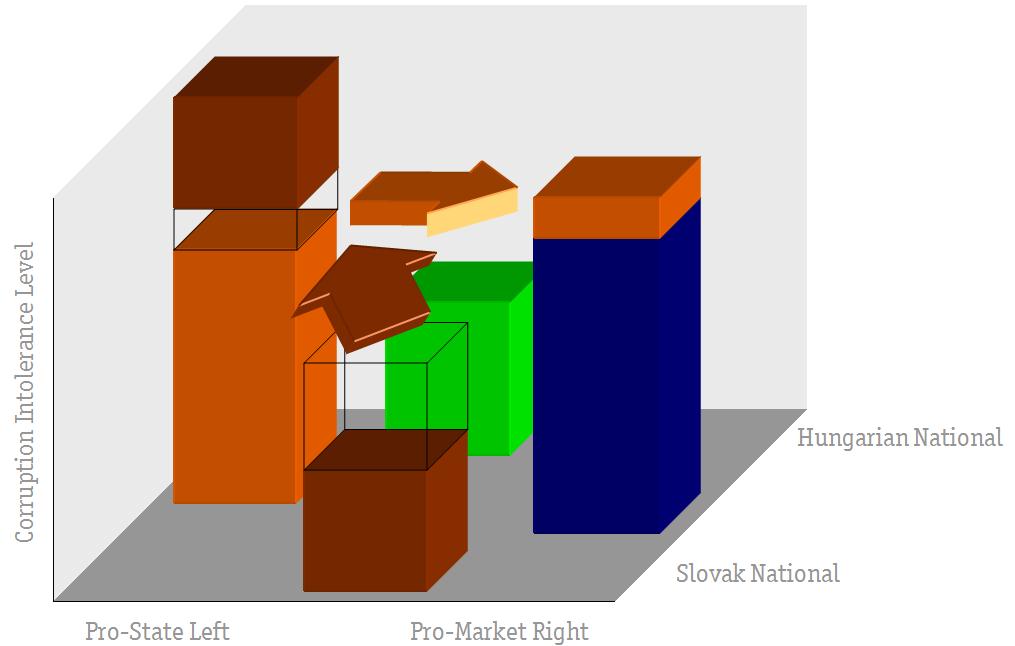

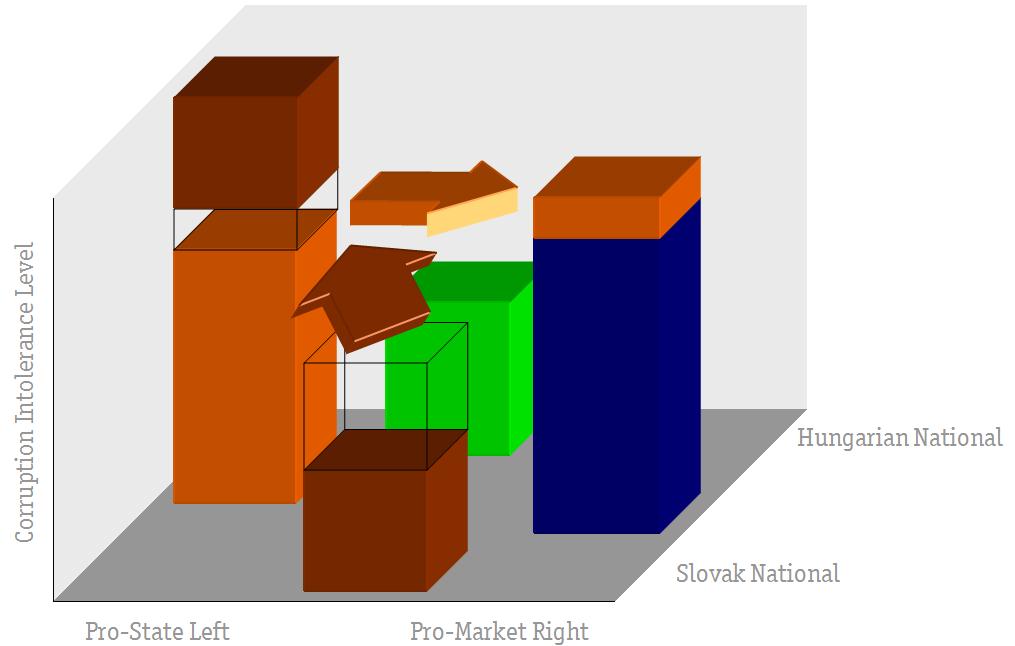

A third level of analysis is necessary to solve the “mystery of the shifting Slovak national party voter.” The third level looks at voters motivations and involves a space with (at least) three dimensions. It also involves speculation on the basis of very little data. What is apparent from two opinion polls conducted before the election is that the exodus of voters from Slovak national parties was not distributed evenly to left and right. In fact, nearly all of it went to the left, mainly to Fico’s “Direction.” For the math to work out, however, this must mean that some of Fico’s voters went elsewhere as well, and the poll evidence suggests that at least some of them went to the new right party Freedom and Solidarity.

These shifts are hard to explain with only two dimensions, particularly the shift from Fico’s statist left party to the and to the most vehemently pro-market right party in the system. At the risk of sounding a bit too much like Rod Serling it is here that our analysis needs a new dimension, one that arrays voters according to their willingness to tolerate corruption and seek ability of established leaders to resolve problems. (I’ve argued elsewhere with Tim Haughton that this dimension is hard to identify because its players change sides: the anti-corruption party of one election may become the corrupt but experienced party of the next election.) By adding this dimension we can make sense of a voter’s jump from “Direction,” which in 2002 and 2006 attracted a significant share of the anti-corruption electorate, to the new and yet-to-be-corrupted Freedom and Solidarity (but which otherwise shares almost no programmatic positions with Fico’s “Direction.”) Corruption sensitivity may also explain much of the shift from the two Slovak national parties to the by-no-means-clean but still less corrupt “Direction,” a shift which is less surprising because Fico had already gone quite far in adopting Slovak national themes. (It also probably explains some of the shift within the Hungarian electorate from the more established of two Hungarian parties to its newcomer alternative.)

Slovakia’s political shift in 2010 thus reflects not a fundamental shift from left and right but only a left-to-right shift in the votes of those most highly sensitive to corruption, a shift that is likely to endure only until the emergence of a new anti-corruption party (perhaps left, perhaps right, perhaps Slovak national) in a future election cycle. Nor does it reflect a fundamental decline in the strength of the Slovak national position but rather a shift of Slovak national voters from the smaller parties with stronger emphasis on national questions to Fico’s larger and more diffuse but sufficiently national alternative. Whether that shift will endure depends on the emergence of a new national alternative, either through the formation of a new party or the reformation of the Slovak National Party.

Dimension 3: Shift of most "corruption intolerant" from SNS and HZDS to Smer (brown arrow) and Smer to SaS (orange arrow). Shifts also occurred within the "right" (from SDKU to SaS) and within the Hungarian national (from MKP-SMK to Most-Hid) but for simplicity's sake those are not shown here.

Why We Should Care

Those who look occasionally at Slovakia can be excused for experiencing a bit of déjà vu. The names of the some parties have changed slightly from the 2002 Dzurinda government, but the names are about the only change. Substitute one Hungarian party for another (“Bridge” for the Party of the Hungarian Coalition), and one new pro-market anti-corruption for another (“Freedom and Solidarity” for the now defunct Alliance of the New Citizen) and the array is pretty much the same. Not only that, but ten of the fifteen cabinet posts are in the hands of the same party that controlled it in 2002 (or its analog) and seven of the fifteen ministers served in the 2002-2006 cabinet (sometimes heading the same ministry). Although the government is the nearly the same, however, the times are different and it will face new challenges.

Economics: Renewed but limited pro-market reform

The 2002-2006 Dzurinda government used its small majority to pass major economic reforms in taxation, health care, education, the labor market and other aspects of the foreign investment climate. The restoration of essentially the same coalition could potentially signal the continuation of major reforms, but by the same token, the magnitude of the shifts between 2002 and 2006 (and the relatively minor rollbacks introduced by the Fico government between 2006 and 2010) may limit the scope for further changes which would push the government’s policy significantly out ahead of the voters’ preferences (especially since I would argue that many of those who supported “Freedom and Solidarity” did so for its novelty and cleanliness rather than its radically pro-market approach.)

Minority and foreign policy: Back to the West, but not without reservation

Although economic questions are the ones that most clearly unite Slovakia’s new coalition, the parties also share a common pro-Western outlook and (relatively) accommodating views on ethnic co-existence and national identity. And since such questions are arguably more sensitive to tone and manner than economic policy, it may be in this realm that the new coalition has its greatest impact on Slovakia and the region. But even this will not be easy. There is still a wide gap between the Hungarian party, “Bridge,” and the its Slovak partners in government on what constitutes appropriate support for minority culture, and the Slovak parties in the coalition cannot risk appearing weak when dealing with the assertively national government in neighboring Hungary. Nor will relations with the rest of the EU be easy, especially since the parties of the current coalition, in an reversal that had more to do with domestic electoral politics than programmatic position, campaigned on a platform of rejecting the EU bailout of Greece and must now figure out how to back down gracefully without appearing to have caved in.

Coalition longevity: Sensitive issues, numerous factions but few alternatives

In addition to “Freedom and Solidarity’s” outlying position on economic issues, and “Bridge’s” outlying position on minority policy, the coalition will also need to deal with the outlying cultural policy preferences of the Christian Democrats (who have already introduced questions about an agreement with the Vatican and who differ sharply from “Freedom and Solidarity” on questions such as gay marriage and drug legalization.) And all of the major coalition partners will need to deal with two smaller groups that entered parliament on the basis of preference voting on the electoral lists of the two new parties: a civic movement called “Ordinary People” which gained election on the list of “Freedom and Direction” (preference votes elevating its representative from the last four places on the list to near the top), and the Civic Conservative Party which gained election on the list of Bridge.

These complications together raise questions about the longevity of what is in effect a six-entity coalition that cannot afford to lose even four of its seventy-nine deputies without also losing its majority. Slovaks are themselves quite divided over the coalition’s prospects, though the opinions tend to reflect partisan hopes rather than measured assessments. The survival of the 2002-2006 Dzurinda government for nearly four years bodes well, but that coalition could rely on Meciar’s relatively weak party to offer tacit support. The Radicova’s coalition, by contrast, has fewer potential reservoirs in the opposition and correspondingly less ability to deal with defections. That said, the coalition’s members also have correspondingly fewer options and may stay in a coalition because it is the only alternative. (Since no female prime minister in postcommunist Europe has ever served out a full parliamentary term, Radicova has the chance to achieve yet another first, though Jadranka Kosor in Croatia has the chance to outlast her in terms of pure longevity)

Opposition prospects: Fico’s burden

Given the large number of potential stumbling blocks for the governing coalition, the next several years in opposition may bring “Direction” strong poll support. The prospects for the Fico’s return to government, however, depend on his ability to open up new coalition possibilities while maintaining the integrity of his party. Whether Fico undermined his coalition partners or not, it is fair to say that he did not do a good job of preparing for the weakness of those parties. Fico’s use of good vs. evil rhetoric to characterize the opposition may have helped at the polls, but it significantly weakened his leverage in prying apart the opposition parties and finding a coalition partner or two among their ranks. Unable to count on the return of Meciar or the resurgence of the Slovak National Party, Fico will need to figure out how to fight a good fight in opposition while at the same time preparing for a potential alliance with some of the coalition partners. And he will have to do so while satisfying the diverse constituencies within his own party—which range from nationalist to cultural liberal, from statist to entrepreneurial—and do so without the perks of government. He managed this well between 2002 and 2006, but it may be harder to do so with a parliamentary delegation that is both larger and more reliant on the resources of the executive.

The big picture: Right and new

Slovakia, like Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic, has elected a “right” wing government (fulfilling Joshua Tucker’s June 9 prediction in the Monkey Cage ), but the meaning of “right” varies considerably from nationalism and cultural conservatism in Hungary (combined with some remarkably statist efforts in economic policy) to its pro-market meaning in the Czech Republic (along with some cultural conservatism) to the pro-market and culturally (relatively) liberal combination that has emerged in Poland (where both the major alternatives claim the “right” label) and in Slovakia. In the long run, Slovakia is likely to see the alteration of the two main streams—statist and national against pro-market and ethnically accommodating—but the nature of the balance will be continually subject to readjustment brought about by the birth of new parties and the death of others. The “new” rather than the “right” may be the real story of recent elections throughout the region, and come the next election cycle, the “new” is more likely to be left or national.

![ScreenClip [3]](http://www.pozorblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/ScreenClip-3.png)

![ScreenClip [4]](http://www.pozorblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/ScreenClip-4.png)

![ScreenClip [5]](http://www.pozorblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/ScreenClip-5.png)

![ScreenClip [2]](http://www.pozorblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/ScreenClip-2.png)

![ScreenClip [6]](http://www.pozorblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/ScreenClip-6.png)