Almost a month ago, I reported doubts about the poll produced by the previously unknown pollster AVVM. Last week, AVVM issued a new poll, but though it only increased my doubts, I decided not to report on it because even too-credulous (or circulation focused) Pravda described the results as “strange” (cudny) and a search of other major news outlets produce other stories worth responding to and trying to correct. And yesterday an article in SME by Miroslav Kern (“Pre-election juggling with preferences“) dealt nicely with the issue in broader terms. I try not to do what the Slovak press is already doing well (and despite my occasional criticism, there is a lot that they do well) and so I figured there was nothing to write about here.

Almost a month ago, I reported doubts about the poll produced by the previously unknown pollster AVVM. Last week, AVVM issued a new poll, but though it only increased my doubts, I decided not to report on it because even too-credulous (or circulation focused) Pravda described the results as “strange” (cudny) and a search of other major news outlets produce other stories worth responding to and trying to correct. And yesterday an article in SME by Miroslav Kern (“Pre-election juggling with preferences“) dealt nicely with the issue in broader terms. I try not to do what the Slovak press is already doing well (and despite my occasional criticism, there is a lot that they do well) and so I figured there was nothing to write about here.

And then, in a search for results of another idiosyncratic poll (Presov University, on which more later) I found myself on the website of Novy cas.

I generally do not read Novy cas, as it does not have a particularly serious reputation, but I realize now that I should read it more often, for a variety of reasons. My first reaction to the Novy cas election website (after getting over my annoyance that it required me to download Microsoft Silverlight to even work) was “Wow.” Not only does the website look great (waving Slovak flag and all) but it had a “Your Ideal Quiz” (because of Silverlight I can’t actually link to it but the page it is on is here: http://volby.cas.sk/) that actually asked pretty good questions, showed the result of each answer on the suitability of particular parties and, when I tried to make answers point to a certain party, actually increased the score for that party. So far so good.

I generally do not read Novy cas, as it does not have a particularly serious reputation, but I realize now that I should read it more often, for a variety of reasons. My first reaction to the Novy cas election website (after getting over my annoyance that it required me to download Microsoft Silverlight to even work) was “Wow.” Not only does the website look great (waving Slovak flag and all) but it had a “Your Ideal Quiz” (because of Silverlight I can’t actually link to it but the page it is on is here: http://volby.cas.sk/) that actually asked pretty good questions, showed the result of each answer on the suitability of particular parties and, when I tried to make answers point to a certain party, actually increased the score for that party. So far so good.

Novy cas also has lots of party information all in one place: tagged news stories, party list, party program (with an interesting mini-wordle that shows the most common word in the party’s program), and development of party preferences over time. This last, however, raised some questions: it listed only one poll per week, but polls in Slovakia are not done on a weekly basis so the polls must come from different sources and so cannot be easily compared. It did not list the sources, so I had to reconstruct it by comparing the data to my own poll database. The first of the four turned out to be FOCUS, the second Polis and the third and fourth…AVVM (a detail that Kern didn’t know or was too polite to mention). Let me restate that in stronger terms:

The self-proclaimed “most read daily newspaper on the internet” is (without telling anybody) basing its election infographics on the product of an untested polling firm with polls that are highly problematic.

Spot the Problematic Poll

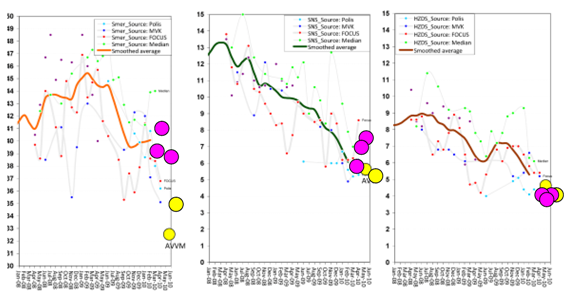

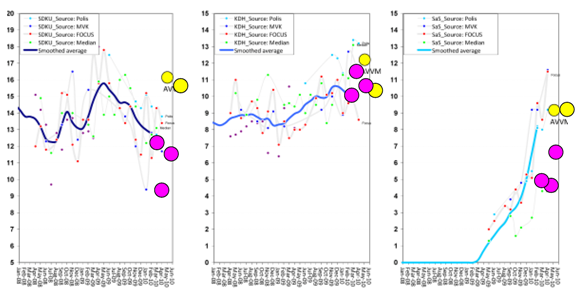

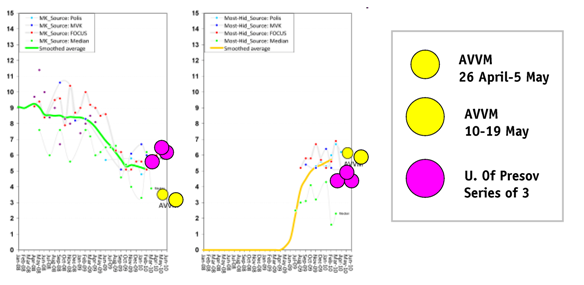

How do we know that AVVM is problematic. In my previous post on AVVM’s first poll, I showed that the firm’s results were far from the median polling numbers of other firms or even from the overall range of those results. The second AVVM poll does not change this assessment in any meaningful way, as the following eight graphs show (AVVM is in yellow; the Presov University poll that I discuss below is in pink):

For the current government parties, AVVM’s second poll is not so out of line. In its first poll AVVM produced exceptionally low results for Smer (orange), though by the second poll this had moved up (and other polls had moved down) until it lay in a more normal range. Likewise AVVM is in the normal range for SNS and HZDS.

Among the Slovak opposition parties, AVVM produced fairly average results for SaS and KDH but quite high for SDKU.

It is for smaller parties that AVVM produces the oddest numbers (both in real and especially in percentage terms. Most-Hid results are fairly average but numbers for SMK are exeptionally low–lower even than the low results produced by Median.

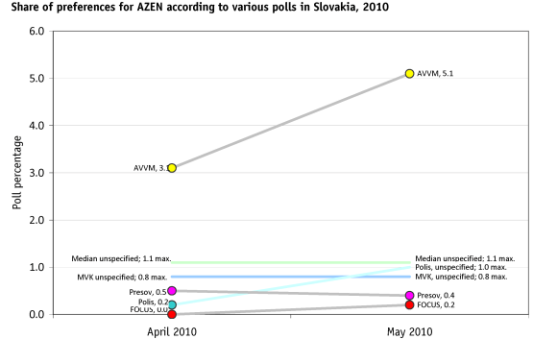

Of course the biggest variation from the norm, and the one that attracted Pravda‘s “strange” headline is the party’s results for AZEN, the new party formed by HZDS defectors Zdenka Kramplova and Milan Urbani. I have not created a dashboard graph for this party because its numbers are actually so low that most polling firms do not report it. To compensate for the lack of full data, I’ve created an approximation graph which gives AZEN the benefit of the doubt (assuming that it just barely misses the threshold for reporting). Even giving it the benefit of the doubt, the results are striking:

AVVM results for AZEN are so far from the norm of the other four major firms (and from the Presov University poll as well) that they simply cannot be taken seriously. It may be that AVVM is right and the others are wrong, but nothing in my experience would suggest that to be the case.

Furthermore, the explanations for this divergence given to SME by AVVM director Martin Palásek are so bad as to disqualify the firm from any further consideration:

- The first explanation: “the party is first on the alphabetical list of parties” and may therefore draw additional support (To prove I’m not making this up: “Konateľ AVVM Martin Palásek výsledok AZEN vysvetľuje najmä tým, že sú prví v abecede, a tak ich uvádzali aj na anketových lístkoch”.)

If AVVM hasn’t figured out some way to control for this then either a) its polls do not deserved to be published anywhere or b) I will be able to win a significant share of Slovakia’s vote simply by registering a new party under the name “Aardvark Alliance”

If AVVM hasn’t figured out some way to control for this then either a) its polls do not deserved to be published anywhere or b) I will be able to win a significant share of Slovakia’s vote simply by registering a new party under the name “Aardvark Alliance” - The second explanation: Party chair Urbani “is among the most popular HZDS politicians” (“ponúkol tvrdenie, že Urbáni patril k populárnym politikom HZDS“). This is in some ways even worse as it reveals a willingness to follow conventional wisdom rather than the hard data which is the only currency of pollsters (except of course that they accept money from parties to do polls). In fact my I cannot find any evidence that Urbani has ever appeared among the lists of “most trusted” politicians conducted regularly by MVK, even though these sometimes contain as many as 30 names. So much for AVVM.

Spot the Ambitious (but Still Problematic) Poll

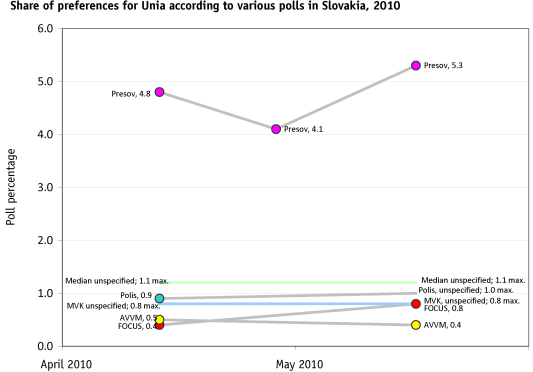

In the same general category as AVVM but with important specific differences are the polls conducted by university students at Presov University. These are fairly consistent with the other polls: just a bit high for Smer and SMK, a bit low for HZDS and SDKU and Most-Hid. For three parties the Presov numbers are further from the norm: low but moving in the right direction for SaS, high and moving in the wrong direction for SNS and shockingly high for Unia. For those who have forgotten, Unia is a merger of three economic and cultural liberal parties: Slobodne Forum (SF), which split from SDKU in the 2004, Civic Candidates (OK) which split from SDKU in 2008 (I think), and Liga -Civic Liberal Party (Liga-OLS) founded in 2008 by former officials of SDKU and ANO. Merging three parties with extremely low preferences into a single party and then adopting an entirely new name seems in retrospect to have been poor tactics as since its formation Unia has regularly polled less than the previous totals for its component parties. Except in the Presov University polls, as the graph below shows:

As with AVVM on AZEN, it is hard to take the Presov University numbers seriously on Unia since they are so far out of line even giving the party the benefit of the doubt on polls where its results are not reported.

It is hard to be as critical of this effort as it is of AVVM, first because it has not been used by a major newspaper without any effort to mention problems or discriminate among its strengths and weaknesses (though that is more the fault of Novy cas than AVVM itself), and second because from everything I can find out about it, it is a laudible educational effort that is open about its methodological limits, cites the geographical areas in which the poll-takers worked, and openly discusses its choice of question and the rationale for it. I am still not sure that I understand how they actually went about the questioning or whether their decision to use party leader names rather than party names is a good way to measure preferences, but at least they are trying something new and explaining why they are trying it. For that I give them great credit, even if I don’t feel like I can include their poll results in my overall average.

The area around the station is full of billboards. Amongst those of the centre-right Slovak Democratic and Christian Union – Democratic Party (SDKU-DS) and the Christian Democratic Movement (KDH) are several of the Slovak National Party (SNS). SNS’s pitch to voters is to pluck at xenophobic and nationalist heart strings. Whilst one of the billboards declares the party’s desire to ensure ‘that our borders remain our borders’ (a clear criticism of the big neighbour to the south), another wants to ensure ‘we don’t feed those who don’t want to work’ underneath a picture of a large, heavily tattooed Roma. Given Presov’s large Roma minority, this is a poster which sadly might be quite effective.

The area around the station is full of billboards. Amongst those of the centre-right Slovak Democratic and Christian Union – Democratic Party (SDKU-DS) and the Christian Democratic Movement (KDH) are several of the Slovak National Party (SNS). SNS’s pitch to voters is to pluck at xenophobic and nationalist heart strings. Whilst one of the billboards declares the party’s desire to ensure ‘that our borders remain our borders’ (a clear criticism of the big neighbour to the south), another wants to ensure ‘we don’t feed those who don’t want to work’ underneath a picture of a large, heavily tattooed Roma. Given Presov’s large Roma minority, this is a poster which sadly might be quite effective.

By the time Iveta Radicova speaks it is already over two and a half hours since the event was supposed to start and the rain has been almost unceasing. The water has seeped through the fabric of my shoes and has made my feet all wet. After a few words from the woman who could be prime minister in a few weeks time, all of the party candidates assemble on stage for the grand finale> a rousing rendition of the campaign song ‘Modra je dobra’ (‘Blue is Good’). It’s a great song, originally recorded by the Czech band ‘Zluty pes’, but after so long standing in the rain with soaking socks all I think about is that maybe ‘Modra je dobra, ale mokra nie je’.

By the time Iveta Radicova speaks it is already over two and a half hours since the event was supposed to start and the rain has been almost unceasing. The water has seeped through the fabric of my shoes and has made my feet all wet. After a few words from the woman who could be prime minister in a few weeks time, all of the party candidates assemble on stage for the grand finale> a rousing rendition of the campaign song ‘Modra je dobra’ (‘Blue is Good’). It’s a great song, originally recorded by the Czech band ‘Zluty pes’, but after so long standing in the rain with soaking socks all I think about is that maybe ‘Modra je dobra, ale mokra nie je’.

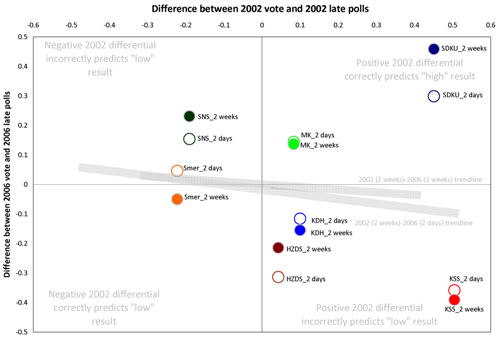

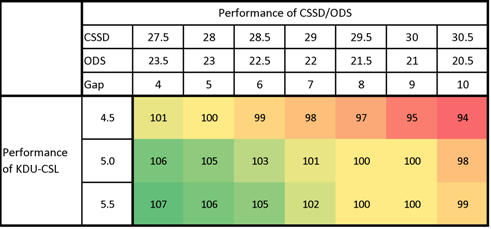

Two-and-a-half months ago I finished up a blog post on poll predictiveness with a cliffhanger:

Two-and-a-half months ago I finished up a blog post on poll predictiveness with a cliffhanger: