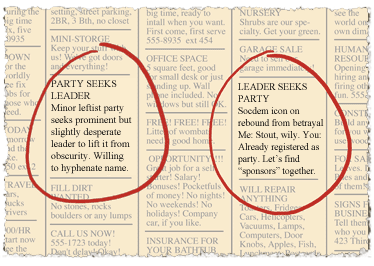

Now that the dust has settled and the world has moved on to other things, it is time for a post-mortem of what happened. (I wish, in retrospect, that time had permitted me to publish my pre-mortem which, because it revealed certain electoral incentives for SaS to hold its ground and not swerve in this game of chicken, was less inaccurate than my usual predictions. Alas.). In trying to figure out why the decision happened as it did (and then happened differently two days later) I think the best framework is Kaare Strom’s model of three party goals–votes, office and policy–which I modify here to take into account the international circumstances related to this of this vote. For each party I offer a rather schematic four-arrow diagram that looks like the one below.

|

|||

For each of the diagrams, the size of the arrow reflects the degree to which a particular factor is important in shaping a party’s position while the color of the arrow indicates the policy inclination of that factor:

With these annotations, I would suggest that the factors within Slovakia’s party system looked roughly as follows:

Let’s start with the easy cases and work toward the harder ones. |

|||

![ScreenClip [3]](http://www.pozorblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/ScreenClip-3.png) |

Slovak National Party (SNS)

SNS is a fairly easy party to assess in this regard because of its relative political isolation and narrow message.

All of this makes SNS’s “no” decision quite easy. It was the only party whose members actually voted “no” rather than abstaining or absenting themselves. |

||

![ScreenClip [4]](http://www.pozorblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/ScreenClip-4.png) |

Slovak Democratic and Christian Union (SDKU)

SDKU, almost despite itself, faces pressures in favor of the EFSF. Things would be a lot better for this party if the issue had never arisen. But it did…

Radicova faced pro-EFSF messages in every direction, particularly from the one source–abroad–that she faced more prominently than anybody else. |

||

![ScreenClip [5]](http://www.pozorblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/ScreenClip-5.png) |

Christian Democratic Movement (KDH)

KDH tends to work closely with the SDKU, though not always–and they themselves have been responsible for a past vote of no confidence (though in that case it came at the end of a term and merely shortened the government’s duration by 3 months). KDH faced similar pressures to those of SDKU but much lighter.

While not as vulnerable on the issue, KDH faced incentives similar to those of SDKU and remained loyal on this question. |

||

|

Most-Hid (Bridge)

Parliamentarians of Most-Hid also remained supportive of the EFSF, though if KDH’s reasons were a weaker reflection of SDKU’s, Most-Hid’s were weaker still.

Also part of the Most-Hid parliamentary club were 4 members from the Civic Conservative Party, ethnic Slovaks who had at best a loose relationship to Most-Hid itself. Of these one opted to support the coalition while the other three

|

||

| So much for the relatively unconflicted parties. Two other parties evince a more mixed structure of incentives, which I try to lay out below. | |||

![ScreenClip [2]](http://www.pozorblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/ScreenClip-2.png) |

Freedom and Solidarity (SaS)SaS faced perhaps the most difficult choices in this conflict but after a considerable time in negotiation ended up opting for its initial policy orientation (though this may not have hurt its voter orientation–we shall see)

The actions of SaS here will significantly change its electoral and coalition parameters, though whether for the better remains to be seen. Much may depend here on the actual success of the EFSF and of Smer. If both perform poorly, Sulik may be in a position to return to government (albeit in bad odor), but if either does well, his chances for returning the party to the political position it had on 10/10/2011 will be much smaller.

|

||

| Finally, there is one party in all of this that must be regarded, in the short run at least, as the big winner. This party, too, had mixed incentives but managed to balance them well enough to achieve some major goals. | |||

BeforeAfter |

Direction (Smer)For Smer the emergence of the EFSF question–an issue that like the recent debt ceiling question in the US could not easily be avoided and did itself allow a 50/50 compromise solution–provided signficant political opportunities without significant risks.

Smer in opposition has been dealt an excellent series of hands and has played them quite well. At its upper levels It has developed into a well-organized and well-managed organization that knows how to take advantage of opportunities. But though Fico seems healthier and more comfortable in the role of main opponent than of the lead executive, he and his party cannot resist pressure that pushes it toward the power and position that can only be achieved in government. At present, it looks as if this is where the party is headed, though it must be noted that its high levels of support have a tendency to ebb when voters are faced with an actual choice in the polling place (or perhaps more significantly, with the choice to go out and enter the polling place).

|

||

Slovakia has used up about two of its 15 minutes of fame, and minus a minute used in the 1993 split, a few minutes used by Meciar in the mid-1990’s and some seconds devoted to its rapid turnaround, it probably has about eight minutes left. At least it hasn’t yet shown any risk of wasting its fame on victory in the Eurovision Song Contest.

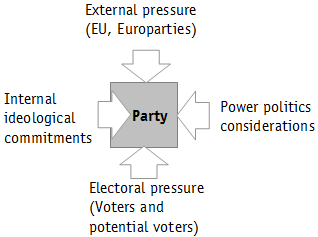

![ScreenClip [6]](http://www.pozorblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/ScreenClip-6.png)

Oscar Wilde once wrote that there is only one thing worse than being talked about and that is not being talked about. But in international politics that isn’t always the case. Slovakia was prominent in the coverage of the three most influential dailies in Europe on Wednesday: Le Monde, the Financial Times and the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Le Monde, for instance, bemoaned the political game being played in Slovakia, wondering in a linked article whether France’s AAA rating will survive the crisis. Sulik’s actions even caused ripples across the Atlantic where Slovakia was also the subject of articles in the New York Times and Washington Post.

Oscar Wilde once wrote that there is only one thing worse than being talked about and that is not being talked about. But in international politics that isn’t always the case. Slovakia was prominent in the coverage of the three most influential dailies in Europe on Wednesday: Le Monde, the Financial Times and the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Le Monde, for instance, bemoaned the political game being played in Slovakia, wondering in a linked article whether France’s AAA rating will survive the crisis. Sulik’s actions even caused ripples across the Atlantic where Slovakia was also the subject of articles in the New York Times and Washington Post.