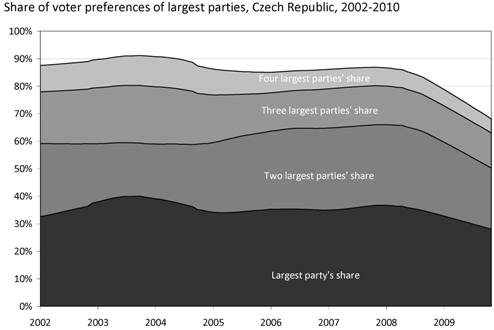

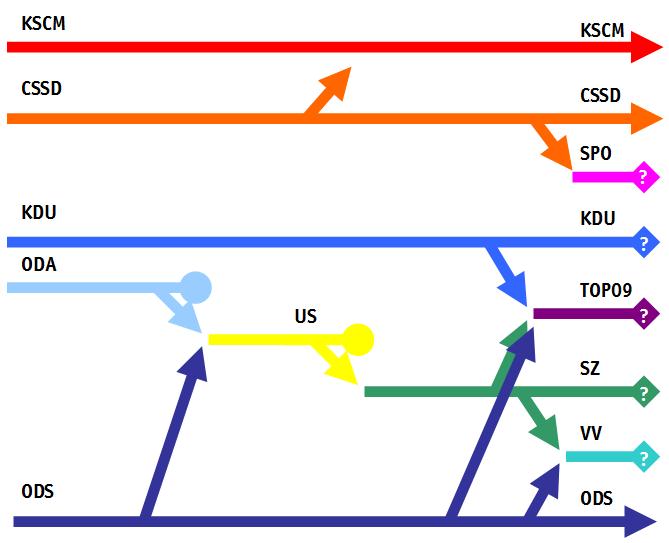

Having just spent quite a bit of time thinking about Czech politics (and expecting to do so again once we get Saturday’s election results) I am struck by how different much of it is from Slovakia–and how much is quite (perhaps increasingly) similar. Unlike Slovakia’s politics, Czech politics still revolves around a left-right axis on economic issues, but the two parties that anchor that axis have weakened and the emergence of new parties clearly suggests the underlying role of at least one or two additional dimensions (corruption is the most obvious). The flux of party death and party birth also seems likely to be similar this year, if not greater on the Czech side. And as in the Czech Republic, the composition of government looks to depend on the ability of parties to cross the 5% threshold of electibilty (see yesterday’s post). But this points back to another difference, extremely narrow but highly consequential for thinking about elections and government formation: in the Czech Republic there is only one party that is hovering around the 5% threshold. In Slovakia, there are four. This is a big deal because those parties are on opposite sides of the spectrum, and every one of the 16 (4^2) permutations has a significant potential impact on who will govern Slovakia.

Having just spent quite a bit of time thinking about Czech politics (and expecting to do so again once we get Saturday’s election results) I am struck by how different much of it is from Slovakia–and how much is quite (perhaps increasingly) similar. Unlike Slovakia’s politics, Czech politics still revolves around a left-right axis on economic issues, but the two parties that anchor that axis have weakened and the emergence of new parties clearly suggests the underlying role of at least one or two additional dimensions (corruption is the most obvious). The flux of party death and party birth also seems likely to be similar this year, if not greater on the Czech side. And as in the Czech Republic, the composition of government looks to depend on the ability of parties to cross the 5% threshold of electibilty (see yesterday’s post). But this points back to another difference, extremely narrow but highly consequential for thinking about elections and government formation: in the Czech Republic there is only one party that is hovering around the 5% threshold. In Slovakia, there are four. This is a big deal because those parties are on opposite sides of the spectrum, and every one of the 16 (4^2) permutations has a significant potential impact on who will govern Slovakia.

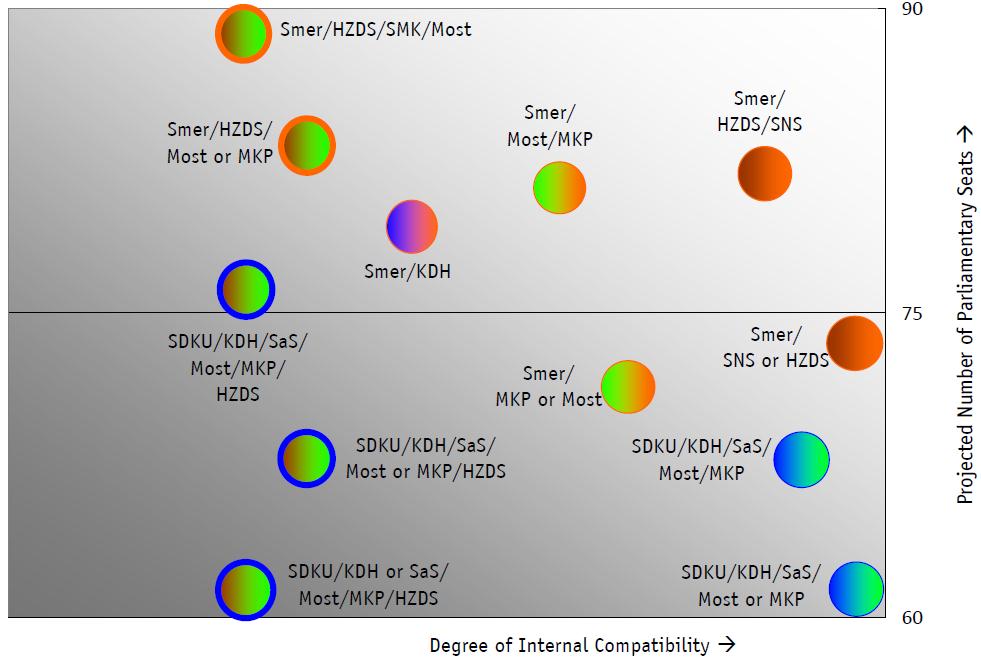

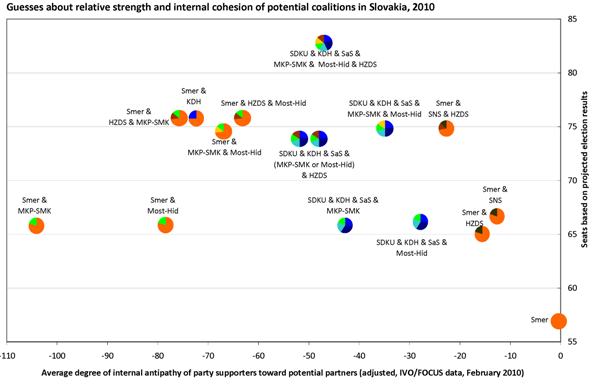

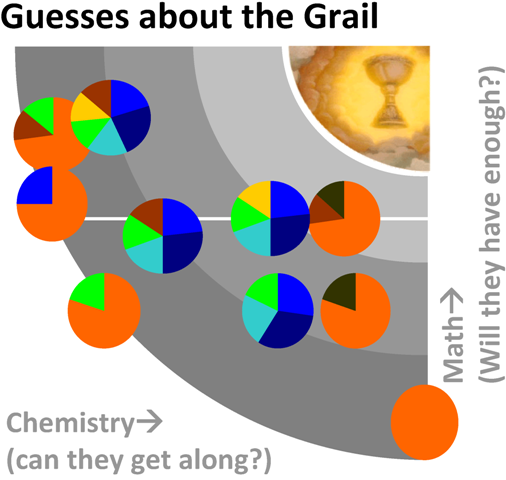

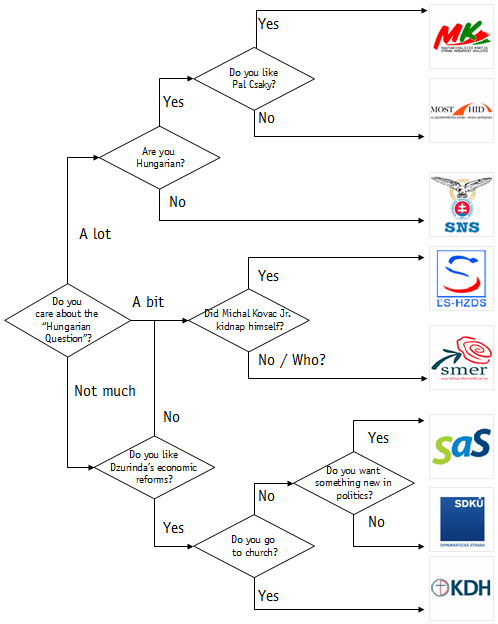

Before we can look intelligently at the effects of the thresholds, however, we need to look at the broader issue of viable coalitions. As I’ve discussed before, coalitions are a combination of math (are there enough seats) and “chemistry” (can they get along). In a post in mid-February, I made certain guesses about both math and chemistry that I summarized in this image:

Since then several things have changed. First, we have much more recent polling data (showing a trend away from the current coalition) and second we have both new statements by parties about potential coalition partners (a delicious.com feed of relevant articles is here), and new data from FOCUS/IVO about what party supporters think of other parties (the original report is here). From this data I can create a new version of the graph on a slightly sounder but still quite imperfect basis.

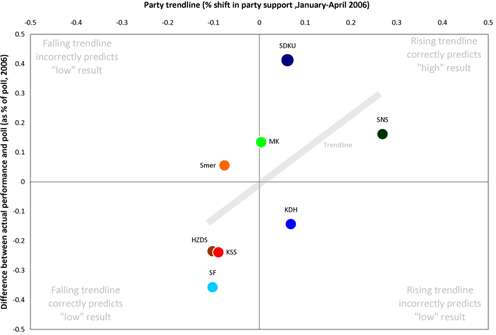

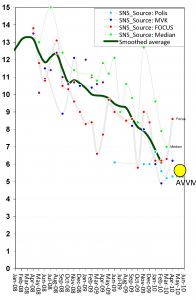

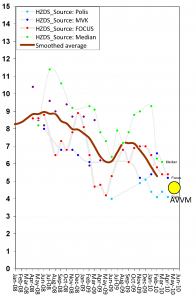

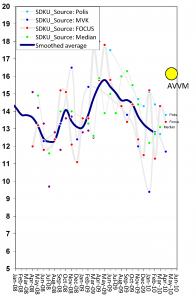

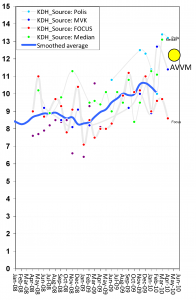

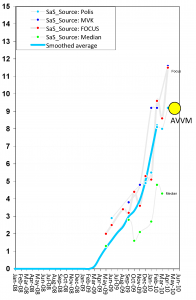

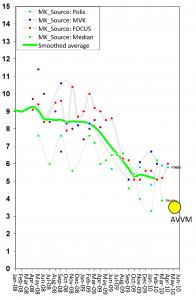

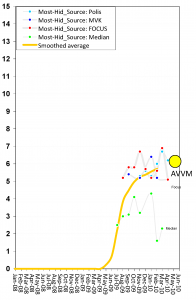

The first imperfection is that I will foolishly make utterly unwarranted guesses about what I think the data now suggests about the final election results, based on the one prediction tool that seemed to work in 2006: pre-existing trendlines. This is, of course, mindbogglingly stupid, when in 2006 I made predictions based on one prediction tool they were in many cases far off. But without a prediction, I can’t go any further. So here I … jump:

| Party | Terribly fraught guess about election outcome (trendline projection adjusted by common sense) |

Number of seats based on fraught guesses |

| Smer | 35.0% | 57 |

| HZDS | 5.0% (see below for nuance) | 8 |

| SNS | 6.0% | 10 |

| MKP-SMK | 5.8% | 9 |

| Most-Hid | 5.2% (see below for nuance) | 9 |

| SaS | 9.0% | 15 |

| KDH | 11.0% | 18 |

| SDKU | 15.0% | 24 |

For the moment, we do not need to worry about the threshold (and in any case the recent averages show all eight parties above the threshold, though in some cases just barely). This will come later. From the percentages above, I calculate a raw number of seats for each party (that can later be nuanced based on threshold questions.)

The second imperfection relates to some way to quantify the “chemistry” (or usually the lack thereof) in a coalition. To do this I have simply taken IVO’s measurement for the overall level of antipathy that supporters of each party has toward each of the other parties. This is imperfect at best but it actually worked quite well as an indicator of most likely coalitions in both 2002 and 2006 (where I ignored it to my peril). That doesn’t mean it will work this time, but it is also fairly consistent with the kinds of statements that parties make about one another, so it is adequate as an initial proxy.

Putting the number of seats on the vertical axes and the level of chemistry (inverse of antipathy) on the horizontal axis yields this lovely graph showing the position of each coalition.

But since neither of these indicators is perfect, it is less misleading about the specificity of the data (and more interesting and attractive) to recast the graph like this:

Here the orange dots represent Smer-based coalitions while orange and dark green/brown represent the Slovak national members of the current coalition. Blues represent parties of the Slovak “Right” while light green and gold represent Hungarian national parties. The quick conclusions:

- No combination achieves the grail of significant size and positive internal chemistry.

- The closest aspirants are the current coalition and the current opposition, which by this estimation each have exactly the same number of seats–a deadlocked 75. In a parliament in which all eight parties enter, a comfortable margin above 75 seats requires broadening the coalition to include somebody from the “other side” either Smer including a Hungarian party or two, or the current opposition including HZDS. More coherent coalitions, by contrast, have almost no chance for electoral success (and, given Slovakia’s complicated 2+ dimensional political landscape, almost never have).

BUT… This assumes that all parties will make it over the threshold. By my estimation, this is actually fairly unlikely

| Party | Terribly fraught guess about chance of passing 5% threshold |

| Smer | 100% |

| HZDS | 50% |

| SNS | 75% |

| MKP-SMK | 90% |

| Most-Hid | 55% |

| Both Hungarians* | 60% |

| SaS | 99% |

| KDH | 99.9% |

| SDKU | 99.9% |

| * More than the product of the two Hungarian parties individually because if one falls short of the threshold, it is probably because the other has gained some of its votes | |

As the asterisk above, suggests, however, it is not enough simply to run an analysis of these parties individually above and below the threshold because there are reciprocal relationships among parties that affect shifts in voters. Although this is certainly true for SDKU, KDH, and SaS, shifts among those three do not have much effect on overall outcomes since they are all above the threshold. The same is not true for the pairing of SNS and HZDS, and especially of Most-Hid and MKP-SMK, whose reciprocity is almost perfect to the extent that it is difficult for MKP-SMK to gain except at the expense of Most-Hid, and (almost) vice-versa. If MKP-SMK falls below the threshold, Most-Hid will almost certainly rise above by about the same margin. The same is true to a lesser extent for SNS and HZDS. As a result, I have built these parings into the overall equation (realizing, but for the moment not caring, that some lost HZDS or SNS vote may go instead to Smer).

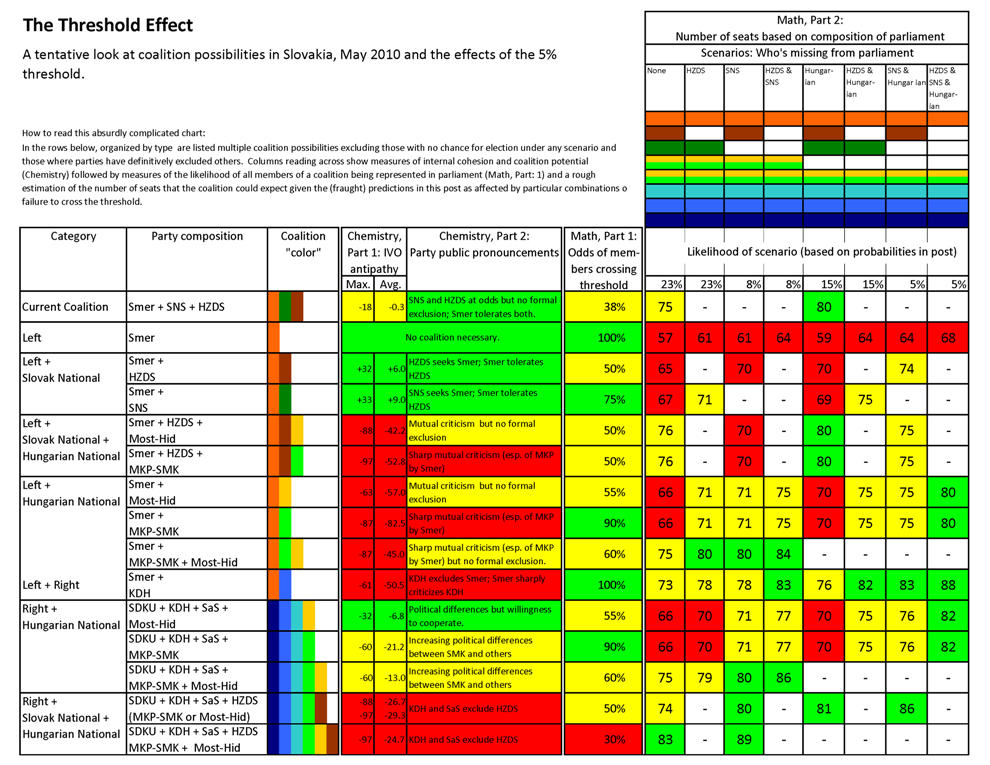

The result of these various calculations is the chart below which identifies eight possible arrays of parties in parliament along the top and eleven possible governing coalitions down the side, identifying the probability of the arrays based on the electoral guesses above, the likelihood that all potential coalition members pass the 5% threshold, and the approximate number of seats gained by each coalition given the parliamentary arrays. Red boxes indicate that a coalition should fall well short of a majority; green boxes indicate a safe likelihood of a majority; yellow boxes indicate something in-between. (The task at hand has so many data points attached to it [and my attempt to squeeze it onto a single page is so obsessive] that it is difficult to compress into something that will fit into this blog column, so it is probably necessary to click on the image to see the full graph.)

So here is all the data in one place, but what does it mean. We can cut the data in two ways: by coalition type and by parliament type.

| Category | Party Competition | Likelihood of parties crossing threshold | Possibilities and Constraints |

| Left + Slovak National (current coalition) | Smer + SNS + HZDS |

38% | If all parties in this coalition make it into parliament, it will likely have a majority. But there is a less than even chance (by my estimation) that both HZDS and SNS will make it. |

| Left | Smer | 100% | Smer will make it into parliament but there is no scenario according to current preferences that would allow it to govern alone (except as a minority government) |

| Left + Slovak National | Smer + HZDS |

50% | These two coalitions depend both on the ability of Smer’s coalition partner to get into parliament and on the absence of at least one (or more than one) other party to provide the necessary seats for a majority. It appears that these coalitions are not viable if both Hungarian parties make it into parliament. |

| Smer + SNS |

75% | ||

| Left + Slovak National + Hungarian National | Smer + HZDS + (MKP-SMK or Most-Hid) |

50% | It would theoretically be possible to add one one Hungarian party to a Smer and HZDS (but not Smer and SNS) coalition, though worsening relations make this increasingly unlikely. Fico would have to be desparate to chose this option, but if trends continue he may indeed face relatively few options. |

| Left + Hungarian National | Smer + MKP-SMK or Most-Hid |

100% | The members of such a coalition are almost certain to get into parliament (it is highly unlikely that both Hungarian parties will fail), but it only becomes really viable if the other Hungarian party does not make or if both SNS or HZDS fail. Fico may, however, have a hard time forming a coalition with a party (MKP-SMK) that has become the most recent direct target of his campaign. |

| Smer + MKP-SMK + Most-Hid |

60% | This coalition would have a clear majority but it is only as likely as the weakest of the Hungarian parties getting into parliament. It is also highly unlikely that Smer would opt for two feuding Hungarian parties (a recipe for disaster) if he could manage any other coalition. | |

| Left + Right | Smer + KDH |

100% | This coalition–which is almost certain to have both members in parliament at levels that produce a majority–actually stands in for any coalition between Smer and one of the current “right wing” Slovak parties. But it is almost impossible to imagine either of the members of this coalition wanting to do this, since both would not suffer with their supporters and especially since KDH unconditionally excluded the possibility and Smer excoriated KDH in response. |

| Right + Hungarian National | SDKU + KDH + SaS + MKP-SMK + Most-Hid |

60% | This coalition would probably have enough votes for a majority (though if both Slovak national parties enter parliament that is in question) but it is dependent on both Hungarian parties entering parliament which is far from a sure bet. Several months ago this coalition did not seem likely to have a majority. Today with declines in the Smer and increases in SaS it has become plausible. The recent citizenship-law issue, however, raises questions about the acceptability of MKP-SMK for the Right that are difficult to answer at present. |

| SDKU + KDH + SaS + (MKP-SMK or Most-Hid) + HZDS |

100% | If one Hungarian parties does not make it into parliament, there is still a chance for it to come close to a majority but only two of three of the parties currently on the line fail. Interestingly a failure by one of the Hungarian parties actually helps magnify the chances of a coalition including the other, making the current sharp competition between the two Hungarian parties more rational than it might seem. If we see a continuation of the emerging differentiation between MKP-SMK and Most-Hid related to Hungary’s dual citizenship law, then only the variant involving Most-Hid becomes viable, but this, of course, would depend on Most-Hid actually making it into parliament. | |

| Right + Hungarian National + Slovak National | SDKU + KDH + SaS + (MKP-SMK or Most-Hid) + HZDS |

50% | If both Hungarian parties do not make it into parliament, the current opposition could theoretically top it off with HZDS but this is unlikely since SaS and KDH have expressed reluctance to join with HZDS and it is in any case dependent on HZDS making it into parliament (at best 50-50). This unlikely option is probably Meciar’s last chance to play kingmaker before the end of his political career: if both SNS and HZDS enter parliament, then HZDS’s choice matters; if SNS does not make it, then the likely coalition combinations to not offer much hope for Meciar to play any role. This is the way the [party] may end, not with a bang but with a whimper. (If, however, the current right parties continue to distance themselves from SMK, Meciar’s bargaining power increases slightly as he could offer his party as an alternative to SMK in a coalition with Most-Hid) |

| SDKU + KDH + SaS + MKP-SMK + Most-Hid + HZDS |

30% | There is a slight chance if all of the current major parties succeed that this coalition of all current opposition parties and HZDS would be theoretically possible alternative, but its likely that some other smaller combination would still gain a majority. |

Or we can look at it another way: What are the consequences for coalition and government formation depending on who crosses the threshold and who doesn’t:

| Who’s missing from parliament: | Likelihood of scenario: | Possibilities: | Most likely government |

| No one | 23% | If all of the major parties make it over the threshold, these numbers give roughly equal numbers of seats to the current coalition and the current opposition (plus the two new opposition parties). One of these might just get enough seats to govern. If there is a perfect deadlock, a government would require one party to switch slides. This is becoming increasingly unlikely and could lead to a Czech Republic scenario of weak, bare majority or minority governments until the disintegration of one of the parliamentary parties (not impossible in current circumstances) allows for a new configuration or new elections. | Current coalition or current opposition |

| HZDS | 23% | If either HZDS or SNS fail to make it into parliament, then the current opposition actually has a chance at a majority coalition given the current estimates. Alternatively Smer could try and pry either KDH or one Hungarian partys away from the current opposition but it is hard to imagine the magnitude of promises this would take to get them to leave a more ideologically consistent, if far more ungainly coalition of opposition parties. The dynamic chances if MKP-SMK becomes anathema to both sides, in which case there is no clear majority for either side. | Current opposition |

| SNS | 8% | ||

| HZDS & SNS | 8% | ||

| One Hungarian Party | 15% | If one of the two Hungarian parties is the only one not to make it into parliament then the stage is set for a continuation of the current coalition or force some sort of cross-the-lines coalition such as the (now ruled out) Smer-KDH coalition or the ungainly coalition of the current opposition plus HZDS. The latter might be possible if the it is MKP-SMK that falls below the threshold, but the numbers make the slightly less likely of the two scenarios. | Current coalition |

| HZDS & one Hungarian | 15% | If one Hungarian party fails and one of the Slovak national parties fails, there are a variety of possibilities very close to a majority: Smer+SNS, Smer+the Hungarian Party, or the current opposition. | Current Coalition, current opposition, or Smer plus a Hungarian party |

| SNS & one

Hungarian |

5% | ||

| HZDS & SNS & one Hungarian | 5% | If a Hungarian party fails and both Slovak national parties fail, then it will again come down to who–if anyone–can (and is willing to) draw the remaining Hungarian party. The current opposition would have the upper hand here, but would they take it? | Current opposition |

Any way we slice it, it looks as if the thresholds will be key. More than half of the coalition possibilities rely directly on parties that are just on the threshold of survival and those that do not are still dependent on threshold effects to determine whether they will muster a majority and whether there are coalition possibilities that may be more attractive to some potential members. We will not have a very good idea of what is even possible until we the results are in. The announcement of KDH’s exclusion of Smer at the beginning of the week led me to think that there may not be quite as much coalition speculation as in the past because of the hardening of opposition-coalition lines, but the increasingly sharp reaction of both Smer and SDKU to MKP-SMK’s position on the Hungarian citizenship law may bring us back to a position of active coalition jockeying but as the case of the Czech Republic shows, government coalition-making gets much harder if one major party is not coalitionable.

Thanks to Michaela Stankova of the

Thanks to Michaela Stankova of the

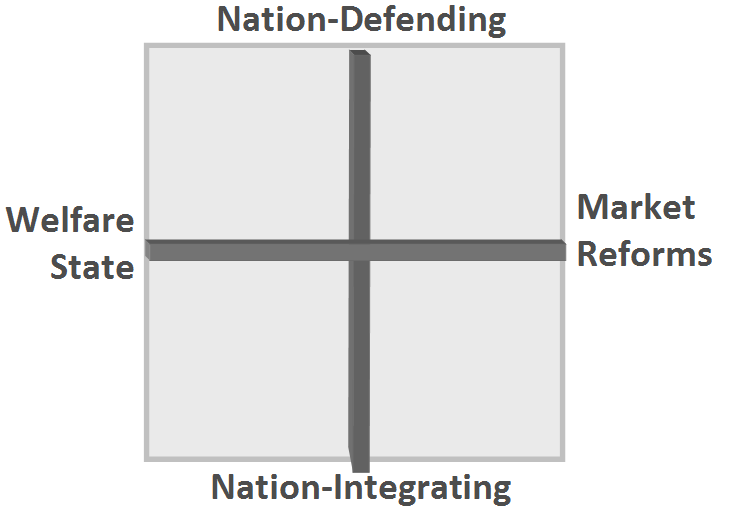

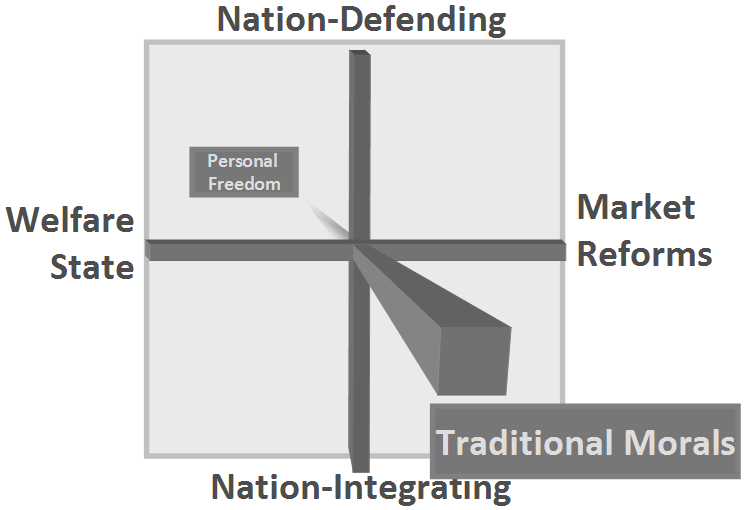

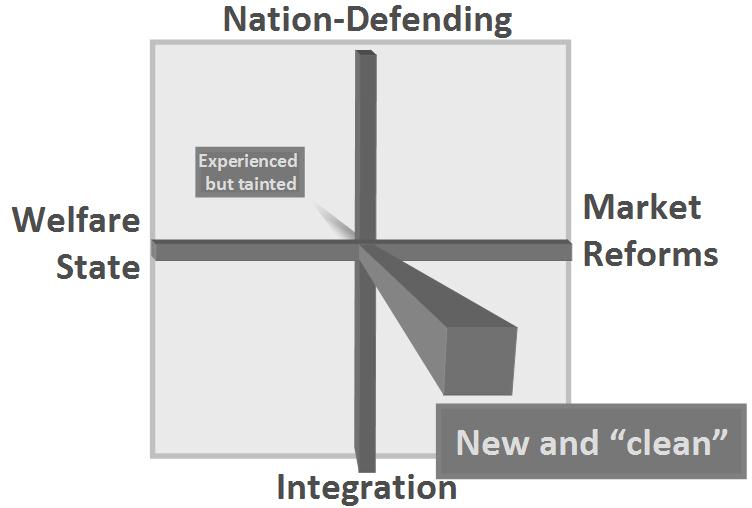

This gets a bit complicated, of course, because “nation integrating” means, “Slovak nation defending” and its rival pole is not so much “Slovak nation integrating” as “Hungarian nation defending” but I simplify it here because the main area in which Hungarian parties and Slovak parties agree on this side of the axis is the need to integrate Slovakia into European structures. Regardless of their labels, the important question is the degree to which these axes are independent of one another or somehow aligned so that positions on one are closely related to positions on the other. This is an open question in changing circumstances.

This gets a bit complicated, of course, because “nation integrating” means, “Slovak nation defending” and its rival pole is not so much “Slovak nation integrating” as “Hungarian nation defending” but I simplify it here because the main area in which Hungarian parties and Slovak parties agree on this side of the axis is the need to integrate Slovakia into European structures. Regardless of their labels, the important question is the degree to which these axes are independent of one another or somehow aligned so that positions on one are closely related to positions on the other. This is an open question in changing circumstances.

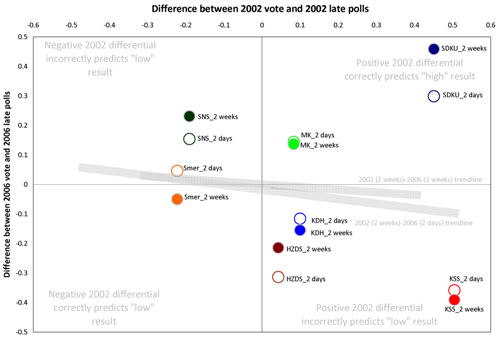

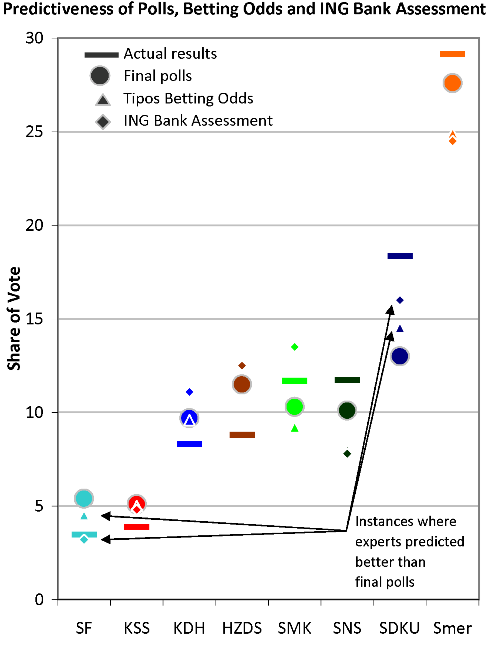

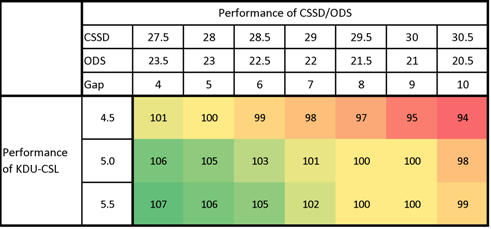

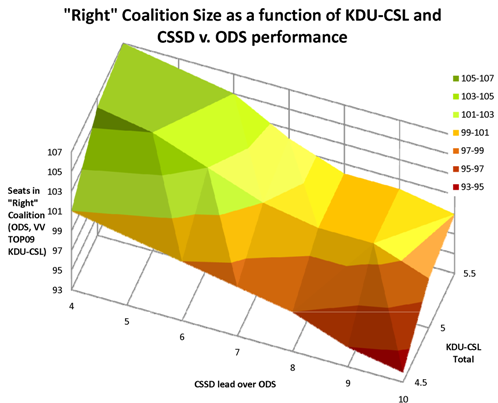

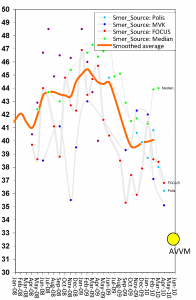

Two-and-a-half months ago I finished up a blog post on poll predictiveness with a cliffhanger:

Two-and-a-half months ago I finished up a blog post on poll predictiveness with a cliffhanger: