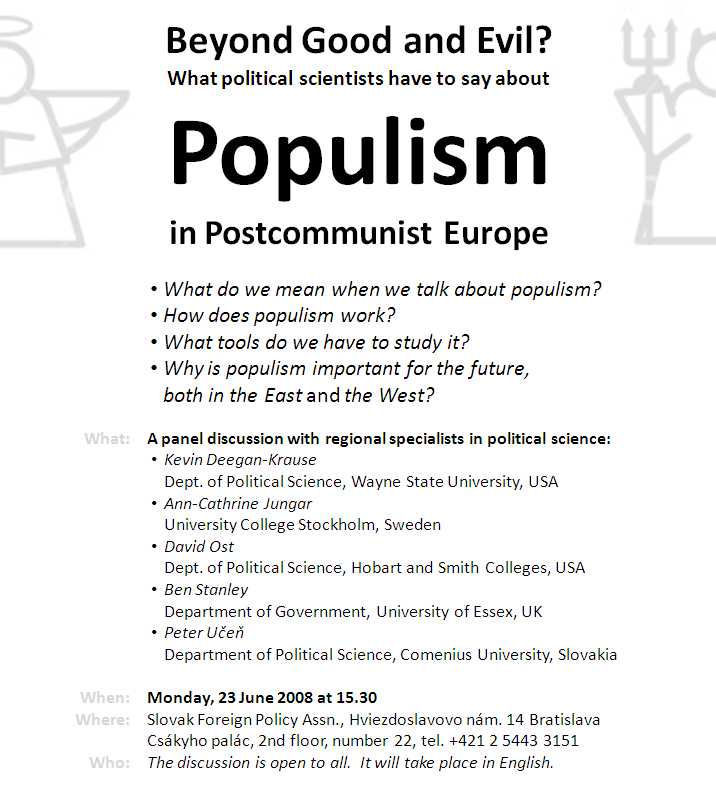

Populism in Postcommunist Europe

A panel discussion with regional specialists in political science:

Monday, 23 June 2008 at 15.30

Slovak Foreign Policy Assn., Hviezdoslavovo nám. 14 Bratislava

Thanks to the Slovak Foreign Policy Association, Fulbright Slovakia, the German Marshall Fund, the Department of Political Science of Comenius University, the Institute for Public Affairs, and the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

Ben Stanley

Department of Government, University of Essex, UK

Everything is appended to the term populism and so the question is how to make sense of a term that is beset with vagueness?

Populism often turns in the research up as a ‘problem’ conceived of as a pathology, as a disease of normal politics. This feeds into its analysis. Conceptualizations are almost inevitably normative: populism is over-simplified, overpromising, demagogic. The media is particular responsible, tying populism to undesirable phenomena. It becomes difficult to disassociate populism from demagogery itself.

Is populism therefore doomed? Is it simply a grab-bag of political sins, or can it be useful?

I argue that it is useful but within limits; I argue that it is an ideology but is thin. As such it points to very little, and it must be combined with other things to be anything more

The typical approach to populism has been to try to distill its characteristics. One major strain is that of cultural protectivism, cultural exclusism, but these are an attempt to derive a theory of populism from exhibited features. Laclau points out the “avalanche of exceptions.” For every definition, there is another that is sharply contradictory.

According to the definition I have attempted to derive, Populism attempts to identify a people that is homogenous in interests and identity. In ineluctable opposition to this homogeneous people is a homogenous elite.

In addition there is the promise of returning popular sovereignty to politics (the elites have torn populism away from its roots and it is necessary to restore correct balance). The degree of the popular element has been neglected.

There is also a moral dichotomy. It is not enough to describe them as ontologically different but also normatively different. Within the people is an essential purity which, when popular sovereignty is realized, rights the moral balance.

Since populism is by-definition anti-establishment. Its shape is determined by the values of the elite. The elites are easy to envision but is it possible to envision a people that is relatively stable, permanent. In the past, this was possible in terms of, say, a peasant class. Now the degree of ideological work that people must undertake is complicated by the fluidity of identity.

Populism is therefore a strategic addition to other ideologies. Across Europe the processes of globalization provide a fertile soil for populism. As the possibility of alternative economic system disappears, populists can identify on the basis of opposition to the elite rather than a particular economic class.

David Ost

Department of Political Science, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, USA

I have spent a lot of time in Poland over time, and as I think about the term populism, I’m skeptical about the negative connotation.

The way it is increasingly used in Europe, West and East, it is often simply a charge by liberals, especially economic liberals, who feel excluded that others are being “irrational” and it is a way of keeping people from making claims about economic inequality.

The way the term is used is already used is one that includes a moral dimension.

The other reason that I’m skeptical is that I’m an American. In America the word has a different meaning and Hillary Clinton was frequently characterized as a ‘populist.’ After 2004 the Democrats in the United States had a sense that they were being outflanked by a party that focused on cultural values. The American policy magazine The American Prospect has explicitly endorsed a “populist agenda” that seemed to have a significant role in 2008. Democrats began to talk about real economic issues, popular issues. In the United States it does not necessarily have the connotation of demagogery.

My basic argument is that populism the term, and the demagogic aspects come from the fact that it is difficult to organize class-based appeals in an era of democratization. This has a lot to do with the crisis of the left, the crisis of social democracy. The old measures do not work in an era of globalization but a lot of the economic problems remain and need a new language to express them, which helps produce the phenomenon of populism. As long as left parties believed in and could carry out redistribution, social democracy rather than populism was the ‘other’ to economic liberalism. That is not as true anymore.

Populism is a political style that focuses on emotions. When social democracy was more potent, it too had a strong emotional quality (focusing on inclusion) but it was also tied to a specific set of policies of redistribution, so it was not simply emotional appeals but rather emotional connection to specific policies. Oddly it is the intellectual and programmatic basis that cost it support.

The main reason we hear more about populism is that left wing political appeals have declined. We did not hear much about populism between about 1910 and 1970 when the left was strong. Populism was more important in the strong 19th century tradition in Russia. The next popular use of it came in the early 1900’s by those whose enemy was Wall Street, bit corporate capitalism (as opposed to small scale production). In much of the world after the 1910’s, however, these desires for economic equality got taken over in by an emerging Marxist discourse. Economic discourse could be more easily expressed in those terms, and it included a clear program.

By around the 1970’s the social democratic efforts worked in a variety of states to a variety of degrees, but globalization created changes in the labor structure, complicating class structure, labor process, reduction of physical labor so that classes and class conflict did not make much sense anymore.

What emerged then and became dominant after 1989 was a sense that there is no alternative, that the only thing to be done was to remove barriers. But of course this led to a backlash. Those who became the new liberal elites denounced others as populists. This does not mean that some “populist” leaders did not use misuse the search for “economic alternatives” to pursue other agendas (Meciar and the Kaczyinskis come to mind) but when we think about this, it is liberals, particularly economic liberals who bear responsibility for this because they were the ones who repeated that there was no alternative to market capitalism and, in effect, told anybody with objections: “you’re irrational, you’re not making any sense, you’re dumb.” In asserting that there was no alternative, liberals drive others into the populist discourse.

Ann-Cathrine Jungar

University College Stockholm, Sweden

David is arguing that the cause of populism is that there is too little economic choice in politics; I would like to argue that one of the reason for populism is that there is too little politics in politics.

Populism is one of the most disputed concepts in political science. Many claim that it is useless and fruitless. Today we all sit here arguing that there is something in the concept. It can and should be stripped of its normative connotations (not that we should not criticize messages that we think are wrong). What is the alternative? It is a richer conception than “new political parties” or “anti-establishment” political parties.

My way into this is to study populism as a political expression. It is no longer temporary eruptions of political protest but rather an institutionalized opposition. Parties with populist appeals are in parliaments, in the EU parliament. They make and break governments; they force governments to pay attention to programmatic questions.

I lead a project in on populism and we deal with three populist dilemmas:

The first is the dilemma of populism and liberal democracy. This is an uneasy relationship. Populism portrays democratic institutions as unrepresentative and unresponsive. Political processes have become more complex, by a multitude of actors and levels. Agencies and organizations play a role at all levels. Responsibility and accountability is blurred and distance among political elites is diminished. Complexity of societies and politics has created a demand for simpler, more straightforward. Does that mean they provide a distinct vision? Populism resents institutionalization, particularly institutions that restrict the will of the people. Some encourage more direct democracy. Some encourage less constitutionalization with regard minority rights but in other cases, they may seek stronger constitutional mechanisms to force accountability to the people. Populists specify the popular will but they are actually quite vague about it.

Populist parties differentiate themselves from other parties in terms of their greater directness and lower levels of bureaucratization, but over time they tend to undergo a process of political institutionalization which seems to be necessary for survival, but which contradicts their initial goals and founding methods. Do they accept sources of institutionalization? Are they replaced internally with more democratic structures? Populist parties tend to voice a criticism of the state of democracy in general but within themselves the state of democracy is quite low.

The third dilemma is between populism and internationalization/transnationalization. Populists tend to define themselves in terms of particular groups or a heartland with particular values or goals. There is therefore a tendency to focus on domestic problems, issues and to reject external interference and involvement and yet now they are participating in international networks, in the European Parliament and elsewhere, particular visible in the right wing populists.

Peter Učeň

Department of Political Science, Comenius University, Slovakia

I was supposed to populism in Slovakia but I will not–because somebody is going to ask about it and so we can talk about it in the discussion.The search for populism as a meaningful political science category. I want to talk about what Ben talked about in a much more concrete way.

There is such a thing as political competition in which politicians argue against opponents, throw labels. Within this discourse, populists are those with unacceptable views and unacceptable means. I have a big problem with the ‘metaphysical threat’ of populism because I do not understand what those means, what those methods are in a democracy. Setting these limits of unacceptabilities is extremely difficult. If you are too left, too redistributionist, you may be called populist; if you are too right, especially too religious, you may be called populist. Other usual accusations include “irresponsible promises,” appeal to emotions and a last one is “irresponsible criticism of the government.” A Slovak economist defined it as “irresponsible promising to people of things they do not need.” This is obviously quite problematic

Direct appeal to the people–this is the normal practice of politicians where as focus on program and avoidance of emotions is not particularly distinctive.

Another assumption is that all of these things are “insincere,” that this is a “business of lying.” By this standard the populist’s claim to speak for the people is seen as lies and deception.

The first step is admitting it as an ideology. At another point we will have to make a statement from populism as a way of doing politics. In order to think fruitfully about populism, we need to think more clearly about the ideology itself and what it really involves: anti-establishment appeals? anti-incumbency appeals? political demagoguery? political opportunism? We must discuss how these are different, how they are conceptually different and what they have in common while acknowledging that they sometimes travel together.

Question Period

Audience Member: How can science look at populism from a little higher level, at elitism, globalism, the legitimacy from the point of view of money. How is it possible to go higher, to look from a higher position to see if we can find some broader patterns. In Slovakia when you speak about populism you must be prepared for one question: What happened during the first period of privatization when a huge share of national property moved into the hands of foreign owners. This is why the current government is preparing a new strategy of transformation.

Peter Ucen: The question of what happened in the first couple of years of post communism is really crucial. But as the years pass, people are a bit more relaxed about this. It plays less of a role

David Ost: Those who are do not like populists get the question: “you say you don’t like populism but why did national property end up in foreign hands.” The answer—“there was no alternative”—was a historic mistake by liberals. Answers about economy need to take into account people’s attachment related to their jobs, to their properties and there are certain sensitivities that are not taken into account. Liberals often believe that “there are no alternatives,” and “people will just not understand.” But even if they are formally correct—and I do not think that they are—it is not good politics and simply drives people into the hands of so-called populisms.

Ben Stanley: key here is the discourse of authenticity and legitimacy that was violated by the transition. Parts of the transition were ‘disembodied’–it had to be done (it was thought) without asking the people about their actual interests. It also has an identitarian aspect in that cultural identities are violated. Transformation was experienced as a violation of the primary political expectation that people would be at the center of political transformation. The removal of politics from ‘people’ during the early transition has a long legacy. This line of division is potentially potent.

Ann-Cathrine Jungar: We need comparative research, concepts to help us to understand, calls for comparisons but within Europe and elsewhere as well. How would you understand that we have populists both in the older democracies as well as new ones? Are there explanations for what happen that transcend this difference. In the east we have replacement of nomenklatura with economic elite and EU accession; there is a similar feeling with many older democracies that the EU is over involved. It is intriguing to see which are the similarities and differences. Maybe it is possible that populism is not that bad at all; maybe it is a useful mechanism to provide voice to people who otherwise feel shut out; it may actually increase turnout and get people engaged.

David Ost: When populism focus on these economic issues, then they are useful; to the extent that they focus on identity and politics of exclusion, then it becomes problematic. If they focus on equality, this is the way to provide for democratic inclusion.

Ann-Cathrine Jungar: Populism might therefore be part of a dynamic process.

Sona Szomolanyi, Department of Political Science, Comenius University: Experience we have after the elections of 2006 in the Visegrad countries. We had to face many analyses coming mainly from Western analyses that populism is increasing and that it is dangerous for these countries–it is an a priori Western assumptions. Despite the fact that there is a relative precise defintion, given what you’ve talked about, what isn’t a populist party. It is hard to talk about any party in such a way that it does not seem populist. Given the ways that US candidates for president have appeals to voters and the way that East Central European leaders here. It is difficult to see a difference between Obama and Fico. I disagree with David Ost’s argument that there was an assumption that there was no alternative. I don’t think that the social state has been extinguished here in Slovakia (despite the so-called radical reforms of the 2nd Dzurinda government). The level of poverty here is one of the lowest in Europe; the figures on the welfare state do not show its elimination. Perhaps better to avoid the term populism and to focus on empirical operationalizations and aspects.

Ben Stanley: I would certainly agree with the last. One of the problems with it is the attempt to define and disagree. Some methodological common ground is those of us on the panel have tried to do. And its something also that colleagues that colleagues in Western Europe have begun to do. It is becoming more coherent, but we are still in our early days. We are still trying to convince one another that there is common ground.

David Ost: To take issue in another way, it is not that parties did not deviate from a strict market argument but the presumption that it was somehow illegitimate to offer an alternative, and that liberal media elites and those in the international community would not object. I would not necessarily defend Meciar’s policy but at least those policies held to a certain defense of popular economic protection. There certainly has been an effort by some Western liberals to look down on Central and Eastern European for not chosing their model (particularly the American model).

Ann-Cathrine Jungar: I want to talk to your question, “Isn’t there populism everywhere?” Most of us would agree that this is not a dichotomy but a question of degree; we must be more specific. There are a lot of terms we use in political science that we use in ordinary speech so we need to break it down and do specific research on specific terms: how is the people is defined? how “defined” is the people? Do we talk about classes, social interests, appeals to specific groups? We need to try to avoid what Sartori calls “conceptual stretching” Some are more populist than others.

David Ost: I don’t think its a really useful to determine this because in democratic society because you need to do this or you will lose. Obama’s problem is that he has not been populist enough and he is only recently catching up. Bush was different, turning from class antagonisms based on wealth to ones based on education (the real elites are “the educated” (i.e. the over-educated)).

Ann-Cathrine Jungar: I wonder how populism is different from other similar concepts. It seems in theory to be easy to study “Social Democracy” because there is a party group, but if you really looked at them without a party label, without a group in Europarliament it is really hard to see what they have in common.

Ben Stanley: You can look at populism in terms of its recursive nature: one of the most common phrases is a notion of a “populist moment.” We need to stop the endless theorization to see if anything substantial can be made of this. I do not think there is a problem with having a theory of populism and also cocepts from which it is composed. In theorizing it, I think there is a reason for thinking about it; whether this pans out in reality is the direction in which we should be going.

Peter Ucen: I don’t think that everybody is populist. The line is not clear cut but it is reasonable. It is not only true that some are more populist than others, but some are differently populist. With regard to populism in America, it is used in at least 2 different ways: one is socio-economic distribution, (health care); another is more relevant is the anti-establishment (every American president runs against the establishment, claims that they will take control away from those “guys in Washington.”)

Ben Stanley: it is in the nature of political concepts to take on a life of their own outside of the academy. But of late a whole variety of politicians have begun to “claim” the negatives of populism as positive (“if all of those things are populism, then, “yes” I am a populist.”)

Joerg Forbrig, German Marshall Fund: The key would seem to be what happens when these people are in office. In the west how many have been re-elected? Have they implemented their policies? What is the current Slovak government actually doing in terms of policy that might be considered populist. What do populists really do once in office? Can we reduce social support for populists to the “losers” (If I’m not mistaken, PiS won Warsaw first, not the regions of greatest “loss”).

Ben Stanley: There are good grounds for doubting that ‘objective losers’ are the sole support for these parties, but we do need to make a distinction between those who have been left out and those who can be mobilized in terms of a rhetoric of being left out. Kaczynski won Warsaw as mayor but on the basis of arguing that the reins of power had been seized by the red-pink coalition of liberals and nomenklatura and taken it out of the hands of ordinary people. He introduced thereby a different discourse of winners and losers. Obviously in Warsaw it’s not possible to push the economic winners and losers too strongly. Similar, Samoobrona has benefited from support of (in quite objective terms) quite prosperous farmers whose only problem with previous governments is that they are not more prosperous.

Peter Ucen: There is a thesis that populism is the resort of losers, but that assumes that the only kind of losing is economic. Other dimensions of ‘abandoment, betrayed’ are equally or more important. Populism is not business as usual for politicians but it is increasing. With regard to a litmus test from governing–it is difficult. Populists do not often get into power. This also assumes that something about populism is related to program and policy, but this is often quite fragile once it is power. It is important not to think about populism as being about redistribution. Regardless of what a populist politician says, the core is in something else.

Ann-Cathrine Jungar: A variety of populist politicians are still there, are durable, such as LePen and some others. Many of these leaders make a strong career at the local level and broaden that. These parties also have a variety of programmatic goals that they do bring into the mainstream. Some may succeed to remain in power whereas others disappear. That, however, is the interesting research question.

Ben Stanley: Behavior in power is no more of a litmus test than for any other ideological strain. But we can benefit from looking at the party system as a whole. Are these parties consistently able to affect the parties in terms of the issues that are debated within the system, considered to be of import. We ought to be looking at populist parties not simply as populist parties but as those that combine populism with something else. We need to look at populism as an element of appeal and the ideology to which it allies its policies. Populists don’t look to seize power to be populists; they look to do it to achieve some other goal, for ends that connect to their other ideologies.

Ann-Cathrine Jungar: There is also considerable research on how populist parties do influence political outcomes by influencing the broader discourse, even if they are not in power themselves.

Ben Stanley: One of the sources of popularity of Civic Platform in Poland was a tempered, softened liberalism but not as populist, not pushed as hard, not in a permanent mobilization, permanent campaign.

Audience member: There seems to be some theoretical confusion. You’ve mentioned that parties use populism to get into power, but Slovakia’s Smer continues to use anti-establishment appeals even though it is still in government? How is this possible?

Ben Stanley: It’s not that parties in power cannot use anti-establishment appeals but it does get more difficult. It is difficult to sustain a politics of populism and make the compromises necessary to stay in.

David Ost: I’m not sure why it cannot work that those in power cannot use anti-establishment appeals. Kaczynski made a particular mess of it by arguing constantly that there were enemies around with no letup, no respite. We’re seeing all kinds of changes in party politics. Probably a party using anti-estabishment elites can’t endlessly be in power but it probably can do it for a long time.

Question: Marek Rybar, Department of Political Science, Comenius University: I would really like to ask you to tell us what is the added value of populism. What does it explain better than other concepts?

Peter Ucen: This was an expected question and not asked for the first time. When I was asked for the first time, I didn’t have an answer. Three years later, I have an answer. Now I am convinced that there is. The term populism–I’m going to be very practical–political scientists of your level could explain this with other terms but it would be very long. Populism if properly defined makes the explanations shorter.

Ann-Cathrine Jungar: I started by saying that there are other terms that can be used. Many of my Swedish colleagues talk about “new parties”–but there are some distinct characterists: popular sovereignty, the people, anti-elite, and so on. There are historical legacies in how populism expresses itself. Others talk about “anti-establishment parties”–that is actually poorer than populism its potential for operationalization. It would be really interesting to do a paper on the connections among these concepts. Finally, what about all the voters? Are they fooled? They actually believe this but this actually reflects that people should have an influence on politics; they have not yet turned into cynics. And it is interesting that in this era of individuals that we are talking about “community.” It is problematic if it is too exclusive but it clearly reflects a longing for gemeinschaft. They formulate some dreams that we have about populism. Populism is saying something about populism today; dreams and hopes about ordinary people and something about establishment politicians who are not taking the responsibility that they should.

David Ost: I’m probably the most skeptical of the term but we don’t have to abandon it. We might ask why use categories of justice or democracies. I think populism is a political style, a kind of appeal, an endless phenomenon–because the principle is to appeal to the people and there are always possibilities for groups that feel excluded to use it as political entrepreneurs to make an appeal to the people. To give it up entirely would be a problem. It’s useful. It means something. Populism does tell us something, but it doesn’t tell us very much.

Ben Stanley: My justification would be essentially that it is something I hit upon at the start of my own studies as an intellectual problem. There are various definitions from which I attempted to extract a theoretical core. Is there something coherent in this? Do they actually find these linked together in the political appeals of particular parties. It is therefore an empirical research problem. To those who wonder why I study this, I often ask whether the competing concepts do any better. The field moves forward by proposing concepts and discarding them when they do not work and building on them when they do. I think that is our task here.