![]()

For a party whose name looks in English to mean “least visible” this party will be getting a lot of attention over the coming year. Founded by Bela Bugar, former head of the Party of the Hungarian Coalition (SMK), it may change Slovakia’s political landscape. Or maybe not.

For a party whose name looks in English to mean “least visible” this party will be getting a lot of attention over the coming year. Founded by Bela Bugar, former head of the Party of the Hungarian Coalition (SMK), it may change Slovakia’s political landscape. Or maybe not.

The party’s name actually means “Bridge” in both Slovak and Hungarian. This allows a nice pun by SME–“Bugar’s people divide Hungarians with a bridge (http://www.sme.sk/c/4881801/bugarovci-rozdelili-madarov-mostom.html)–and prompts a lot of speculation by a lot of people about the nature of the new party. In fact, I suspect that it would be difficult for any predominantly Hungarian party to attract more than 1 or 2% of the Slovak electorate, though European election results from this weekend suggest that minority-focused parties can attract more than their ethnic share if the other parties are in bad enough odor. Nor do I think that the new party, despite its name, necessarily expects to gain a large number of Slovak voters. The debate here is primarily about what happens within the Hungarian community.

At first glance, creation of a second major party to represent Slovakia’s Hungarian minority seems extremely dangerous in a country where the electoral threshold is 5% and the Hungarian population hovers around 11%. The Slovak National Party (SNS) here represents the worst case scenario: in 2000 it split its 8% electorate almost exactly down the middle (disillusioning a few of its supporters in the process) between SNS and the “Real” SNS (PSNS) in such a way that each half got 3.5% and neither made it over the threshold. With this example in mind, the establishment of Most-Hid looks like a gamble, especially since, the split follows the SNS-PSNS in another key way: one party gets the more popular leader but little organization, while the other gets the organizational continuity and the uncharismatic new leader who threw out the other one. The difference, however, is significant as well: unlike SNS voters (who could always turn to HZDS) Hungarian voters do not have anywhere else to go, and given the minority status of Hungarians in Slovakia they are relatively well-habituated to turning out rather than staying home.

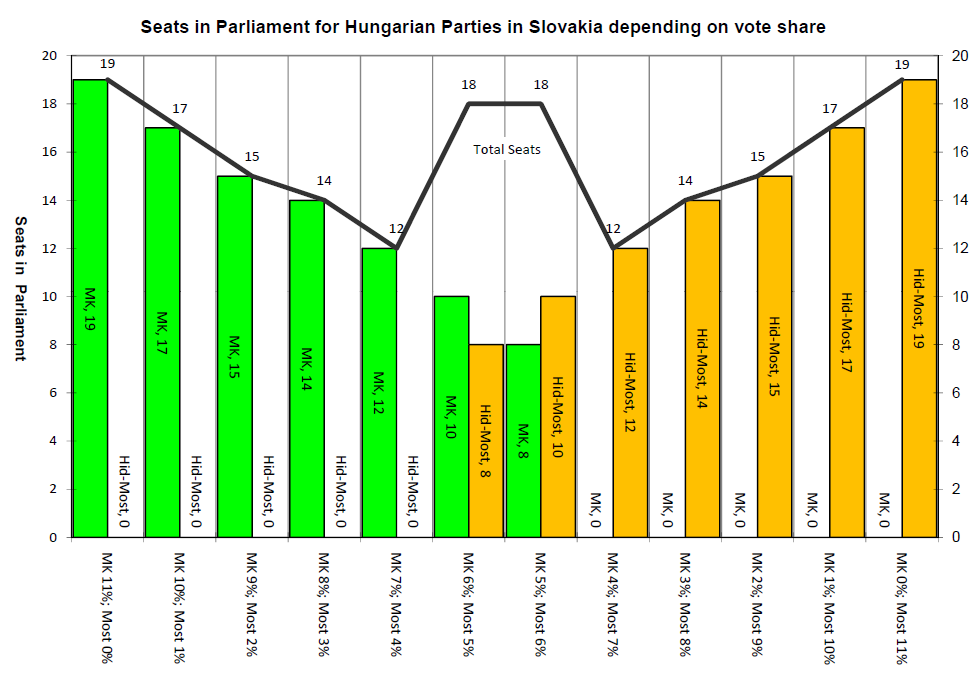

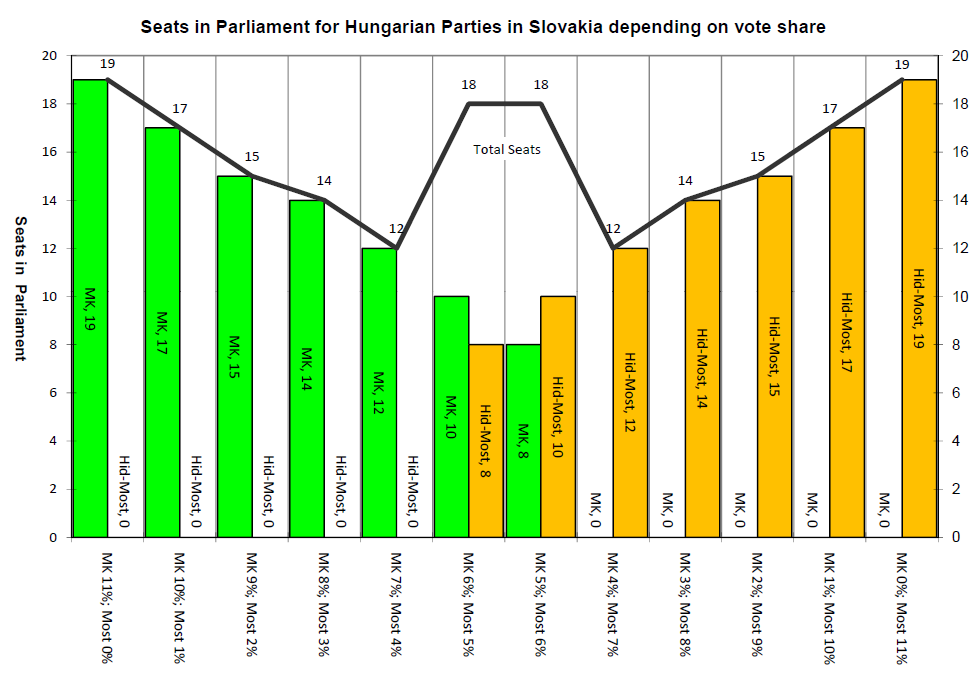

Given these conditions, what is the likely effect of Most-Hid on overall election results. Well in the first place, Bugar has been careful not to exclude the possibility of an electoral coalition with the party he just left, which would more or less return the situation to the pre-1998 situation in which two Hungarian parties competed for share of vote but approached elections in coalition. Even if the parties do go into the election separately, the results may actually not be catastrophic for the Hungarian population. The graph below starts with today’s electoral environment and makes the assumption that a combination of two Hungarian parties will receive 11%. (This is a conservative estimate, slightly below the party’s recent totals in the mid-11% range. Of course it is possible that bitter competition between two Hungarian parties could turn voters off, but it is just as possible that having more defined choices might bring some Hungarians back to the voting booth and, just maybe, that Bugar could attract a few Slovaks, so 11% is probably a bit low.) Under current conditions, a party with 11% would gain 19 seats, one short of SMK’s take in 2006. For the sake of argument I assume that each point gained by Most-Hid reduces the support for SMK by the same amount and then calculate the number of seats according to the current Slovak method for alloting parliamentary seats:

First, and obvious but it should be said, unless the Hungarian party electorate falls below 10%, the emergence of Most-Hid won’t replicate the SNS-PSNS mutual destruction. One of the two parties will gain representation. The next-worst-case scenario not impossible but it is also not as grim as it might seem because of the workings of the electoral system. If Most-Hid (or SMK) were to get 4.99% and the other party 6.01%, the total share of parties would certainly fall short of the possible score, but not by as much as one might suppose since, with fewer parties above the threshold, parties get more seats per vote. As a result, the likey minimum score for total Hungarian representation is 12 seats. Furthermore in half of the scenarios above (I cannot say which is most likely), Hungarian representation does not drop by more than two.

The fact that the creation of Most-Hid threatens a drop but not an elimination of Hungarians in parliament may help to explain Bugar’s calcuations. The step won’t ruin his reputation and increases his options. It is not impossible that Most might be able to attract a significant share of SMK support and become the dominant of the two partners, allowing Bugar to dictate terms, allowing the possibility of an electoral coalition with SMK, even leading to the ouster of Csaky from SMK and a re-unification under Bugar.

Add to this the probability (diminished slightly but still extremely high) that Smer will form the next government and the fact that some within Smer have already responded positively to Most-Hid’s creation (http://spravy.pravda.sk/smer-chvali-bugara-sdku-stoji-za-csakym-d94-/sk_domace.asp?c=A090610_085204_sk_domace_p23) and the creation of the party actually looks like a well-calculated risk. Even the timing is relatively good: a year ahead of elections is enough for the party to build an organization but not too long for the party to languish in opposition obscurity.

Smer may be the real winner in all this: if Most makes it over the threshold, the number of possible coalition partners increases and therefore so does Smer’s bargaining power. If Most does not make it over the threshold but draws away a significant number of voters from SMK, then the seats SMK might have won are redistributed upward and some of them will go to Smer.

The real loser in this are those political scientists (by which I mean myself) who argued that SMK’s strong internal organization and decision-making mechanisms made it more stable and less likely to fragment. But perhaps those same researchers can recover by shifting their focus to study new parties.

—–

One interesting side note: at the time of with the rather poorly-planned announcement of Palko’s KDS, which at the time had neither a website, logo or even name, I have been conscious of how politicians in Slovakia miss chances for using early publicity to establish a brand that no private firm would ever miss. So on the day the rumors about Most-Hid finally reached the daily press I checked to see if anybody had established a Most-Hid website. No, but they did do so by the following day, though the website is empty except for the logo.

Interestingly if I read Whois.com right, the party had already claimed the domain name about 3 weeks ago, at a time when discussions between Bugar and Csaky were still going on! Plus two points for prior planning. Minus one point for good faith bargaining.

Domain-name hid-most.sk [and most-hid.sk]

Admin-name Websupport, s.r.o.

Admin-address c.d.457, Kysucky Lieskovec 02334

Admin-telephone 0904/306 081, 0904/306 081, 0904/306 081

Last-update 2009-05-16

Valid-date 2010-05-12

Domain-status DOM_OK

For once I’ll get the lead on the Slovak press and talk about a poll first, the results of which I have added to the Dashboard. Median published its January poll results today and they have their effects on the overall averages, pushing the MKP-SMK average below 5% for the first time in my dataset, while flattening out the sharp rises of Most-Hid and SaS and softening the drop of HZDS and SNS. We shall see how the press covers it (“CSAKY, BUGAR AND SULIK FALL SHORT!”) but in the context of other polls, its’ rather hard to accept. There are lots of ways to analyze this but for the sake of time and simplicity I’ll simply compare Median to the other three polls taken at approximately the same time (MVK, FOCUS, Polis). On the two biggest parties, Smer and SDKU, the Median result is right in line but on all the rest it stands out to a remarkable degree. Long-established Slovak parties (SNS, HZDS and KDH) score high in Median’s poll. Very high. Meanwhile newly established parties (and SMK) score low. Very low. In fact, for all six of these parties, the Median poll result is not only the outlier, but its addition more than doubles the range of poll values or more (x3 for HZDS, x4 for SAS and x6 for SNS). In other words Median results are more different from the nearest of the three other polls than any of those polls are from one another, as the graph below shows.

For once I’ll get the lead on the Slovak press and talk about a poll first, the results of which I have added to the Dashboard. Median published its January poll results today and they have their effects on the overall averages, pushing the MKP-SMK average below 5% for the first time in my dataset, while flattening out the sharp rises of Most-Hid and SaS and softening the drop of HZDS and SNS. We shall see how the press covers it (“CSAKY, BUGAR AND SULIK FALL SHORT!”) but in the context of other polls, its’ rather hard to accept. There are lots of ways to analyze this but for the sake of time and simplicity I’ll simply compare Median to the other three polls taken at approximately the same time (MVK, FOCUS, Polis). On the two biggest parties, Smer and SDKU, the Median result is right in line but on all the rest it stands out to a remarkable degree. Long-established Slovak parties (SNS, HZDS and KDH) score high in Median’s poll. Very high. Meanwhile newly established parties (and SMK) score low. Very low. In fact, for all six of these parties, the Median poll result is not only the outlier, but its addition more than doubles the range of poll values or more (x3 for HZDS, x4 for SAS and x6 for SNS). In other words Median results are more different from the nearest of the three other polls than any of those polls are from one another, as the graph below shows.

As part of the 20th anniversary commemorations in postcommunist Europe, America.gov (one of the U.S. State Department’s outreach websites) has been soliciting academics and journalists to write on “Challenges of Democracy” in the region (in 400 words or less!). They were kind enough to publish my own thoughts (with no editorial intrusions) along with

As part of the 20th anniversary commemorations in postcommunist Europe, America.gov (one of the U.S. State Department’s outreach websites) has been soliciting academics and journalists to write on “Challenges of Democracy” in the region (in 400 words or less!). They were kind enough to publish my own thoughts (with no editorial intrusions) along with