More from wide-ranging Tim Haughton, who this time sacrificed dry feet to bring a full report of Tuesday’s political campaigning in Slovakia and showed his political acumen and intrepidity by going not to Bratislava, where everybody goes, but rather to Kosice.

More from wide-ranging Tim Haughton, who this time sacrificed dry feet to bring a full report of Tuesday’s political campaigning in Slovakia and showed his political acumen and intrepidity by going not to Bratislava, where everybody goes, but rather to Kosice.

How to Win Votes and Influence People – Some Reflections from Slovakia

Tim Haughton, University of Birmingham

It’s a question which excites and perplexes scholars and practioners alike: what kind of campaigning really works? How best can a political party spend its time and money to attract and hang on to the support of voters?

With the Czech vote behind us, I decide to head to the other half of the federation, where as all readers of this blog know, the Slovaks are gearing up for their elections. Opening the curtains of the sleeper carriage as the train pulls into Kosice station, I am greeted by the beaming smile of Vladimir Meciar, the three-time prime minister of Slovakia. His billboard promises ‘hovorit Pravdu, dat Pracu a urobit Poriadok’ [speak the truth, create jobs and ensure order].

The three Ps are capitalized, reminding me of Public Private Partnerships. Critics of Meciar’s time as prime minister (and indeed his party’s participation in the current government) might suggest that such PPP arrangements are about taking from the state to give to those near and dear to his party. A lucrative and successful partnership for some, but not for the coffers of the Slovak state. As readers of this blog know, Meciar’s People’s Party-Movement for a Democratic Slovakia (LS-HZDS), once Slovakia’s most successful electoral machine is in danger of falling below the 5% threshold. Perhaps to counter the widespread view that the party is a group of silver and grey-haired Meciar devotees, another poster at Kosice station depicts a large group of smiling twentysomethings, declaring that ‘And the young vote LS-HZDS’. Somehow I’m not convinced we will see a rush of first time voters racing to the polling stations to cast their votes for Meciar. The major challenge for Meciar’s party is to convince voters that it makes sense to support the party on 12 June. The party may still have brand recognition and one of the iconic figures in Slovak politics, but it looks and feels like a party well beyond its shelf-life which seems to have lost its raison d’etre.

The area around the station is full of billboards. Amongst those of the centre-right Slovak Democratic and Christian Union – Democratic Party (SDKU-DS) and the Christian Democratic Movement (KDH) are several of the Slovak National Party (SNS). SNS’s pitch to voters is to pluck at xenophobic and nationalist heart strings. Whilst one of the billboards declares the party’s desire to ensure ‘that our borders remain our borders’ (a clear criticism of the big neighbour to the south), another wants to ensure ‘we don’t feed those who don’t want to work’ underneath a picture of a large, heavily tattooed Roma. Given Presov’s large Roma minority, this is a poster which sadly might be quite effective.

The area around the station is full of billboards. Amongst those of the centre-right Slovak Democratic and Christian Union – Democratic Party (SDKU-DS) and the Christian Democratic Movement (KDH) are several of the Slovak National Party (SNS). SNS’s pitch to voters is to pluck at xenophobic and nationalist heart strings. Whilst one of the billboards declares the party’s desire to ensure ‘that our borders remain our borders’ (a clear criticism of the big neighbour to the south), another wants to ensure ‘we don’t feed those who don’t want to work’ underneath a picture of a large, heavily tattooed Roma. Given Presov’s large Roma minority, this is a poster which sadly might be quite effective.

On arriving at the station I endulge in my usual ritual of buying a range of different newspapers. The leading Slovak paper, Sme, is running a story on the recent TV clash between Prime Minister Robert Fico and the head of the SDKU-DS electoral list, Iveta Radicova. It doesn’t make happy reading for the latter (the majority thought Fico had won), but I wonder how much influence these duels really have. Having watched both British and Czech ‘prime ministerial debates’ in recent weeks, I’m reminded that they can generate plenty of press coverage, can seem to have changed the political landscape, but ultimately – in the British case in particular – may have had little impact. In the Czech case if they had any impact it may have been to persuade some undecided voters not to vote for either Necas or Paroubek.

On arriving at the station I endulge in my usual ritual of buying a range of different newspapers. The leading Slovak paper, Sme, is running a story on the recent TV clash between Prime Minister Robert Fico and the head of the SDKU-DS electoral list, Iveta Radicova. It doesn’t make happy reading for the latter (the majority thought Fico had won), but I wonder how much influence these duels really have. Having watched both British and Czech ‘prime ministerial debates’ in recent weeks, I’m reminded that they can generate plenty of press coverage, can seem to have changed the political landscape, but ultimately – in the British case in particular – may have had little impact. In the Czech case if they had any impact it may have been to persuade some undecided voters not to vote for either Necas or Paroubek.

Elsewhere the papers are full of comments reflecting on the impact of the Czech results on the Slovak elections, most of which miss the key factors. For my money, three points are worth stressing. Firstly, electoral thresholds matter and can consign an evergreen (no not the greens, but KDU-CSL) to life outside parliament. The fact that nothing is sacred and that even long-standing parties with seemingly loyal support bases can fail, is a lesson some Slovak parties will need to take on board. Secondly, CSSD’s disappointing result and Paroubek’s departure must have had a sobering effect on Fico. The combative party leader was Fico’s closest international partner who enthusiastically backed Fico in the 2006 election. He has been more than just a political ally as Fico’s attendance at Paroubek’s wedding (in the role of a witness if memory serves correctly) highlights. Thirdly, it has given a filip to the centre-right. ‘If it possible for the assorted forces of the right to defeat what they like to label “lefist populism” in the Czech Republic, then why not here’ , they proclaim?

After checking into my Kosice hotel I head back to the station to take the train to Presov. After having bought my ticket to Presov and a ticket for the sleeper back to Prague, I notice on the back of the ticket to Presov an SNS advert replete with a picture of the old-new party leader Jan Slota and his one-time successor and now predecessor as party leader Anna Belousovova. Moreover, on the back of the ticket sleeve for my ticket and sleeper reservation is an advert for Bela Bugar’s Most-HID party. These both strike me as clever strategies on the part of the parties. Unlike other campaigning materials voters are given, a train ticket is not heading straight for the rubbish bin and perhaps will be looked at more than one during the journey. Smer-SD activists have also been at work. The slow train from Kosice to Presov may not be a glamourous place to campaign, but a party supporter has clearly been hard at work and has left campaign literature material on each of the little tables next to the windows.

The desire to visit Presov is dictated not by a desire to leave Kosice, but to attend an SDKU-DS political meeting where all the party’s stars and wannbe bigwigs are scheduled to attend. Thanks to the inclement weather the outdoor meeting doesn’t begin as planned at 16:00, nonetheless, campaigning doesn’t stop. Decked out in blue waterproofs young activists distribute party material and in a clever touch reminding Slovaks that their team will play in the World Cup starting in a few days time, they give out a red card like the one used by football referees reminding voters to give Fico a ‘red card’ at the election. It is also fascinating to observe how the different politicians behave. Many of the less well-known politicians use the opportunity to circulate and give the waiting crowd their own electoral material. Thanks to the open lists, the possibility of preference voting means that it is important for these candidates not just to encourage citizens to vote for the party, but they need to plug themselves as well, especially if they are well down on the party list. Whatever the merits of such big rallies for the parties as a whole, they are valuable opportunities for wannabe parliamentarians.

The desire to visit Presov is dictated not by a desire to leave Kosice, but to attend an SDKU-DS political meeting where all the party’s stars and wannbe bigwigs are scheduled to attend. Thanks to the inclement weather the outdoor meeting doesn’t begin as planned at 16:00, nonetheless, campaigning doesn’t stop. Decked out in blue waterproofs young activists distribute party material and in a clever touch reminding Slovaks that their team will play in the World Cup starting in a few days time, they give out a red card like the one used by football referees reminding voters to give Fico a ‘red card’ at the election. It is also fascinating to observe how the different politicians behave. Many of the less well-known politicians use the opportunity to circulate and give the waiting crowd their own electoral material. Thanks to the open lists, the possibility of preference voting means that it is important for these candidates not just to encourage citizens to vote for the party, but they need to plug themselves as well, especially if they are well down on the party list. Whatever the merits of such big rallies for the parties as a whole, they are valuable opportunities for wannabe parliamentarians.

Once the meeting starts it follows a clear script designed to build-up to a climax, blending music and speeches. The best speech of the night is given by former PM Mikulas Dzurinda. If a party funding scandal hadn’t forced him to step down as leader of the party list, he would be the most likely alternative to Fico as PM. Dzurinda delivers his five minute speech with gusto, reminding the audience of his governments’ successes, berating Fico for his mistakes, pointing to the success of the centre-right in the Czech Republic and imploring the good citizens of Presov to get out and vote on 12 June.

Tony Blair’s press guru Alistair Campbell and the spinmeister supreme Peter Mandelson were always keen on making sure all the details are correct, acutely aware of the importance of image and symbols. The SDKU-DS leadership, however, have clearly not studied the New Labour handbook. Indeed, I’m surprised by the little slip-ups in SDKU-DS’s otherwise well-presented (and apart from the late start) slick rally. Two of the slips are made by the two bands providing the music. One plays the riff from Bowie and Queen’s ‘Under pressure’ as they warm up. Well, maybe only I noticed that, but during the performance one band plays Bryan Adams’ ‘the summer of 69’. I’m not sure how many of the audience were paying that much attention, but surely a song which describes 1969 as the ‘best days of my life’ isn’t really an appropriate one in the former Czechslovakia. It might have been the ‘best days of my life’ if one’s name was Gustav Husak, but post-68 Czechoslovakia under normalization wasn’t for most Slovaks.

The other attention to detail seemingly missed by the organizers was the exact location of the stand. Whilst it is opposite one of the busiest bus stops in the city and a Tesco supermarket, it is right in front of the town’s main theatre where they are showing a performance of ‘Marie Antoinette’. As I see former finance minister Ivan Miklos and social affairs minister Ludovit Kanik (who introduced the tough neo-liberal welfare reforms during the last SDKU-DS-led government) standing next to the stage all I can think of is the former French Queen’s infamous line to the masses of Paris ‘Let them eat cake’. Perhaps I am reading to much into these observations, but anyone with a good camera and video recorder could at least use the images to poke some fun at SDKU-DS.

By the time Iveta Radicova speaks it is already over two and a half hours since the event was supposed to start and the rain has been almost unceasing. The water has seeped through the fabric of my shoes and has made my feet all wet. After a few words from the woman who could be prime minister in a few weeks time, all of the party candidates assemble on stage for the grand finale> a rousing rendition of the campaign song ‘Modra je dobra’ (‘Blue is Good’). It’s a great song, originally recorded by the Czech band ‘Zluty pes’, but after so long standing in the rain with soaking socks all I think about is that maybe ‘Modra je dobra, ale mokra nie je’.

By the time Iveta Radicova speaks it is already over two and a half hours since the event was supposed to start and the rain has been almost unceasing. The water has seeped through the fabric of my shoes and has made my feet all wet. After a few words from the woman who could be prime minister in a few weeks time, all of the party candidates assemble on stage for the grand finale> a rousing rendition of the campaign song ‘Modra je dobra’ (‘Blue is Good’). It’s a great song, originally recorded by the Czech band ‘Zluty pes’, but after so long standing in the rain with soaking socks all I think about is that maybe ‘Modra je dobra, ale mokra nie je’.

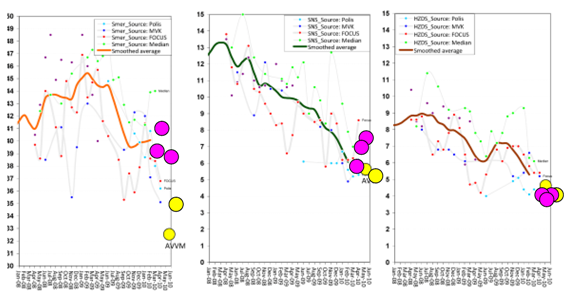

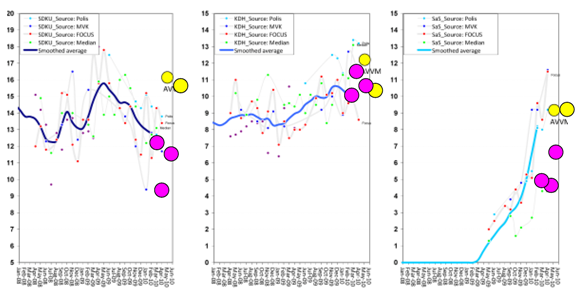

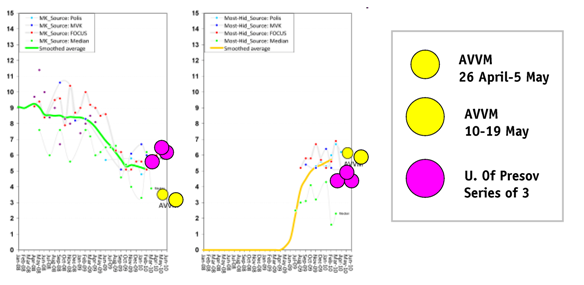

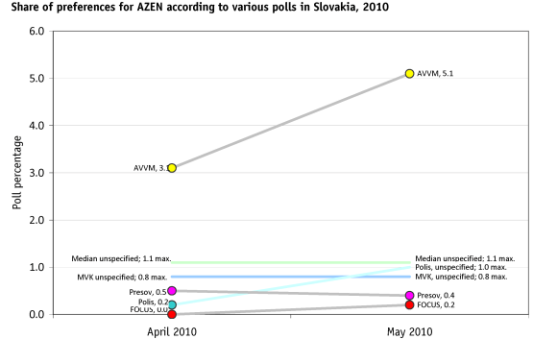

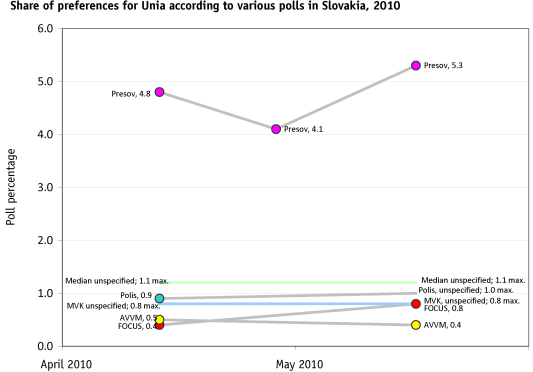

There is an old saying that “figures don’t lie, but liars do figure” (which I’m sure has some equivalent in almost every language) and there is a wonderful book written in 1954 provocatively entitled “How to Lie with Statistics.” In Slovakia’s election coverage in 2010 the challenge is not so much statistical lies as lazyness. Figures appear from various polling firms and they are duly published by newspapers that what people to pay attention whether they have solid basis in fact (nobody’s lying, per se, but they also have no way of knowing whether they are telling the truth) or whether they have any impact. As a case in point take today’s article in SME, “Smer and SaS can score among undecideds.” (HN does the same) It is, perhaps, interesting that this is the case, but the article makes little effort to deal with the two real underlying questions:

There is an old saying that “figures don’t lie, but liars do figure” (which I’m sure has some equivalent in almost every language) and there is a wonderful book written in 1954 provocatively entitled “How to Lie with Statistics.” In Slovakia’s election coverage in 2010 the challenge is not so much statistical lies as lazyness. Figures appear from various polling firms and they are duly published by newspapers that what people to pay attention whether they have solid basis in fact (nobody’s lying, per se, but they also have no way of knowing whether they are telling the truth) or whether they have any impact. As a case in point take today’s article in SME, “Smer and SaS can score among undecideds.” (HN does the same) It is, perhaps, interesting that this is the case, but the article makes little effort to deal with the two real underlying questions:

If AVVM hasn’t figured out some way to control for this then either a) its polls do not deserved to be published anywhere or b) I will be able to win a significant share of Slovakia’s vote simply by registering a new party under the name “Aardvark Alliance”

If AVVM hasn’t figured out some way to control for this then either a) its polls do not deserved to be published anywhere or b) I will be able to win a significant share of Slovakia’s vote simply by registering a new party under the name “Aardvark Alliance”

The area around the station is full of billboards. Amongst those of the centre-right Slovak Democratic and Christian Union – Democratic Party (SDKU-DS) and the Christian Democratic Movement (KDH) are several of the Slovak National Party (SNS). SNS’s pitch to voters is to pluck at xenophobic and nationalist heart strings. Whilst one of the billboards declares the party’s desire to ensure ‘that our borders remain our borders’ (a clear criticism of the big neighbour to the south), another wants to ensure ‘we don’t feed those who don’t want to work’ underneath a picture of a large, heavily tattooed Roma. Given Presov’s large Roma minority, this is a poster which sadly might be quite effective.

The area around the station is full of billboards. Amongst those of the centre-right Slovak Democratic and Christian Union – Democratic Party (SDKU-DS) and the Christian Democratic Movement (KDH) are several of the Slovak National Party (SNS). SNS’s pitch to voters is to pluck at xenophobic and nationalist heart strings. Whilst one of the billboards declares the party’s desire to ensure ‘that our borders remain our borders’ (a clear criticism of the big neighbour to the south), another wants to ensure ‘we don’t feed those who don’t want to work’ underneath a picture of a large, heavily tattooed Roma. Given Presov’s large Roma minority, this is a poster which sadly might be quite effective.

By the time Iveta Radicova speaks it is already over two and a half hours since the event was supposed to start and the rain has been almost unceasing. The water has seeped through the fabric of my shoes and has made my feet all wet. After a few words from the woman who could be prime minister in a few weeks time, all of the party candidates assemble on stage for the grand finale> a rousing rendition of the campaign song ‘Modra je dobra’ (‘Blue is Good’). It’s a great song, originally recorded by the Czech band ‘Zluty pes’, but after so long standing in the rain with soaking socks all I think about is that maybe ‘Modra je dobra, ale mokra nie je’.

By the time Iveta Radicova speaks it is already over two and a half hours since the event was supposed to start and the rain has been almost unceasing. The water has seeped through the fabric of my shoes and has made my feet all wet. After a few words from the woman who could be prime minister in a few weeks time, all of the party candidates assemble on stage for the grand finale> a rousing rendition of the campaign song ‘Modra je dobra’ (‘Blue is Good’). It’s a great song, originally recorded by the Czech band ‘Zluty pes’, but after so long standing in the rain with soaking socks all I think about is that maybe ‘Modra je dobra, ale mokra nie je’.

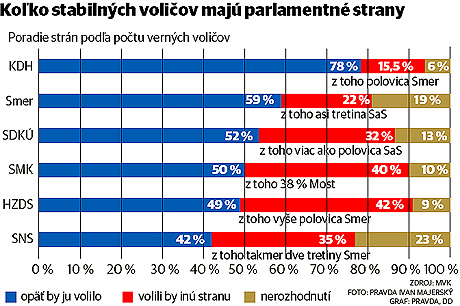

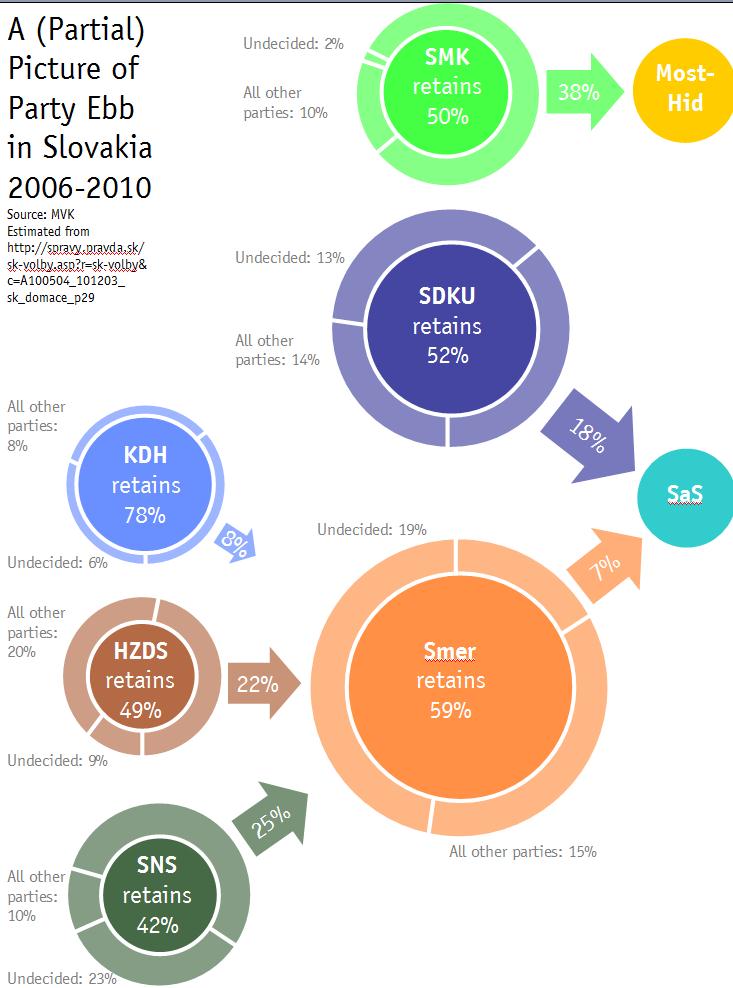

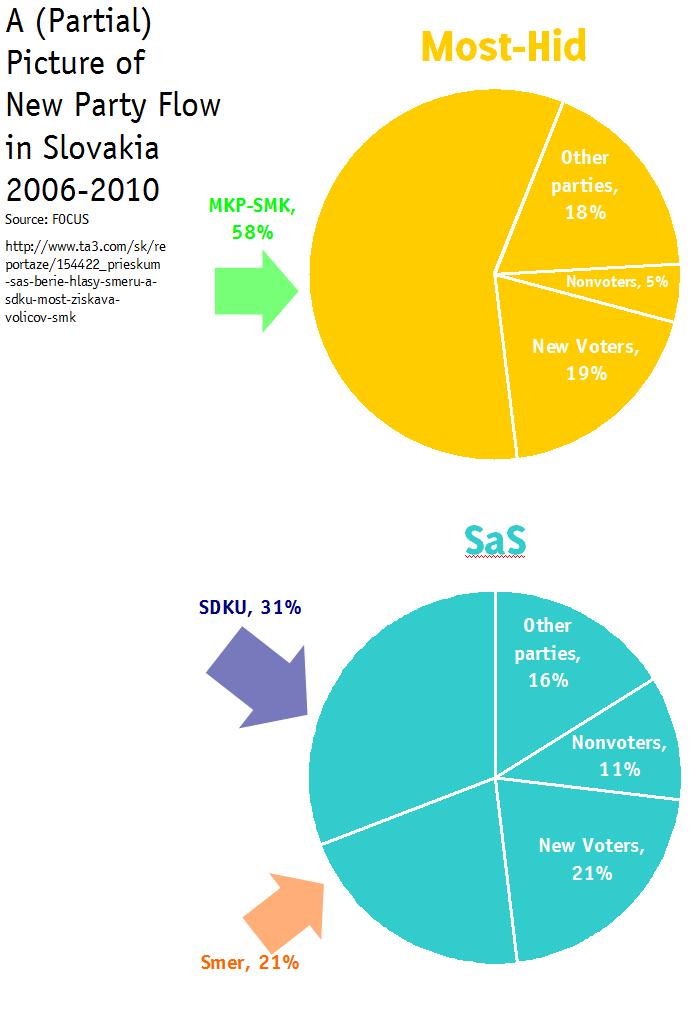

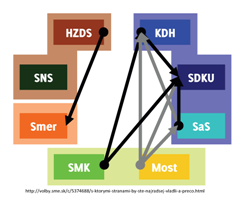

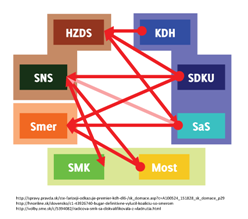

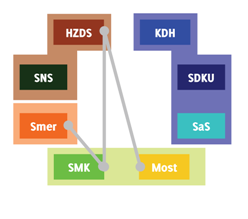

And in any case there is almost no circumstance in which any of these would help create a coalition except, perhaps, the unlikely Smer-SMK-HZDS “coalition from hell” (or as Ben Stanley puts it better than I ever could, “Sounds like a job for the Large Hadron Collider.” So this evidence points toward either a continuation of the current coalition (hard to manage if one of the two Slovak national parties drops out) or its replacement by the opposition (hard to manage if one of the Hungarian national parties drops out)…

And in any case there is almost no circumstance in which any of these would help create a coalition except, perhaps, the unlikely Smer-SMK-HZDS “coalition from hell” (or as Ben Stanley puts it better than I ever could, “Sounds like a job for the Large Hadron Collider.” So this evidence points toward either a continuation of the current coalition (hard to manage if one of the two Slovak national parties drops out) or its replacement by the opposition (hard to manage if one of the Hungarian national parties drops out)…

The smiling gentleman pictured here–

The smiling gentleman pictured here– Thanks to the timing of my students’ exams, piles of undergraduate dissertations to mark and other exciting administrative tasks, I arrived in the Czech Republic late on Wednesday with just one day of campaigning to go. As my wife is a native of Prague the first duty (and pleasure) whenever we visit the Czech Republic is to meet up with the family. In a local watering-hole in the shadow of the Staropramen brewery, with the golden beer quenching our thirst, the debate begins.

Thanks to the timing of my students’ exams, piles of undergraduate dissertations to mark and other exciting administrative tasks, I arrived in the Czech Republic late on Wednesday with just one day of campaigning to go. As my wife is a native of Prague the first duty (and pleasure) whenever we visit the Czech Republic is to meet up with the family. In a local watering-hole in the shadow of the Staropramen brewery, with the golden beer quenching our thirst, the debate begins.

After lingering for awhile I decide to leave and start walking back to Andel to take the tram back to the in-laws. A few hundred metres from the VV stall a German family with three young children are walking in the same direction as me. They probably know little about Czech political dinosaurs or Radek John, but they are really enjoying the taste of the candy floss. Not everything in Czech politics has such a bitter taste, but the tastiest things are sometimes the offerings of the new to the ignorant.

After lingering for awhile I decide to leave and start walking back to Andel to take the tram back to the in-laws. A few hundred metres from the VV stall a German family with three young children are walking in the same direction as me. They probably know little about Czech political dinosaurs or Radek John, but they are really enjoying the taste of the candy floss. Not everything in Czech politics has such a bitter taste, but the tastiest things are sometimes the offerings of the new to the ignorant.