The last post pointed toward a successor that would talk more about dimensions of competition, emphasizing the “non-primary” dimensions. This allows some attention to the emerging question of “niche” parties and points directly to the question of salience that I promised would follow. From this we can then look at the links between the kinds of conflicts and their roots in society (or lack thereof).

The last post pointed toward a successor that would talk more about dimensions of competition, emphasizing the “non-primary” dimensions. This allows some attention to the emerging question of “niche” parties and points directly to the question of salience that I promised would follow. From this we can then look at the links between the kinds of conflicts and their roots in society (or lack thereof).

And one final preliminary note: what follows is far longer and more detailed than anything I intended. The material here pushed itself in this direction and I merely hung on for the ride.)

The analysis in the previous post suggested a fairly wide consensus about the relatively narrow degree of dimensionality in most polities: something more than one dimension, but rarely more than two dimensions, at least not two dimensions of significance equal to the first. What scholars find in most cases–whether they use manifesto data or expert survey data–is configurations that consist of one dominant dimension of conflict along with one or more subordinate dimensions, (analogous to the “one and two-halves party system” metaphor discussed with some disdain by Sartori (1976, 168) or perhaps metaphorically akin to the higher dimensions in string theory which are curved tightly in on themselves). The primary dimension is most often but not always socio-economic. The number, type and strength of non-primary dimensions vary rather significantly from country to country (and, Stoll [2010] would suggest, over time).

The question is how we should handle these various dimensions in scholarly analyses. The major dimension(s) provide(s) a challenge in their composition, in how many issues they bundle. Bakker’s work suggests that in most Western European countries the economic dimension bundles in the GAL-TAN dimension bundle whereas in some (especially Greece and Austria) it does so to a much smaller degree. In postcommunist Europe, by contrast, the overall tightness of the bundling is somewhat lower (both mean and median correlations between economic and GAL-TAN positions are lower by about 0.10).

For the dimensions beyond the primary conflict, problems of definition are different and there are questions of measurement and significance. These secondary and tertiary dimensions are clearer in that they bundle fewer issues, but our everyday vocabulary–and even our scholarly vocabulary–is ill-equipped to deal with these dimensions and the parties that occupy them.

Perhaps the most significant evidence of this inadequacy is the recent emergence of the notion of the “niche” party into active scholarly consideration. A slightly-more-than cursory search of electronic sources suggests that this term has shifted over time from a rather idiosyncratic and descriptive term toward a theoretically-grounded concept.

The etymology of the term “niche” is little help, deriving from the architectural term for “a recess for a statue”(OED http://www.oed.com/?authRejection=true&url=%2Fview%2FEntry%2F126748) into a variety of meanings that imply removal, seclusion, and a general notion of “apartness.” During the past century ecologists have transformed the word into a metaphor of suitability: every living thing has a “niche” outside of which it is not as fit for survival.

Nor does the phrase “niche party” have a long history that would offer suggestions on how it is best to be used. The phrase does not to have been in common use before the early 1990’s, with no mentions at all in the Lexis-Nexis Academic Universe or Google Books databases before 1993. The early uses of the term appear between 1993 and 1999 tend to apply to small parties in systems with two or three dominant parties: the Progressive Democrats in Ireland, the New Democratic Party in Canada, the Ethnic Minority Party and Christian Heritage Party in New Zealand, and Shas in Israel.

Gallagher in 1993 characterizes a “‘niche’ party” as “looking for support from certain groups” and contrasts this strategy with that of a “catchall party” (66, http://bit.ly/ktoN6Q). A later commentator from New Zealand extends this metaphor directly into the realm of aquaculture:

[Green Party co-leader Rod Donald] used “a fishing analogy to describe the difference between a broad-spectrum party and a niche party. The former “‘trawl” to catch as many voters as possible, while the latter use a more selective long line. (Luke, Peter. 1999. “Push-button parties.” The Press. 23 October, section 1, p. 11.)

Niche parties are thus somehow distinctive, small, and unlikely to get much bigger. Beyond these core characteristics, however, the precise identification of niche parties becomes more difficult and the boundaries between definitional and empirical limits begins to blur. More recent definitions help to narrow down the field, but they do not necessarily agree.

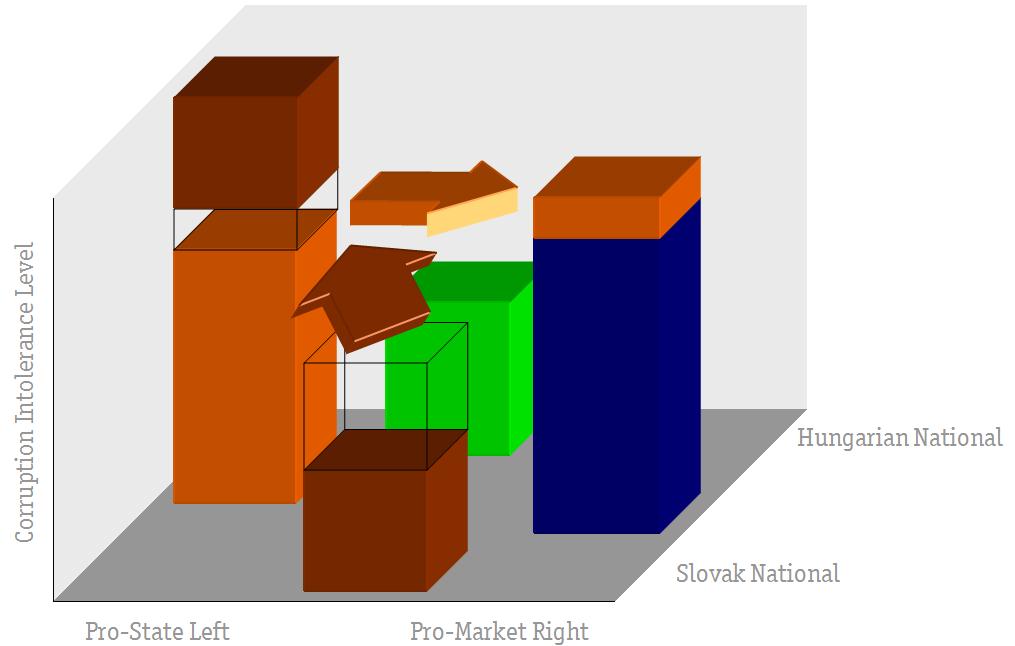

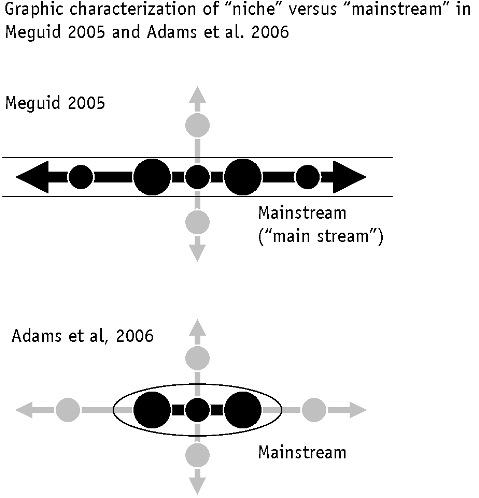

Perhaps the most specific of the recent definitions is the one provided by Meguid in her meticulous 2005 analysis of the interaction between “niche” and “mainstream” parties. It is notable, first, that Meguid defines “niche” against “mainstream” rather than “catchall,” suggesting that the difference lay not (solely) in the way a party seeks to attract its voters but rather (also) in its position within the broader party system. “Niche” here means “away from the main”

Her definition involves three distinct aspects dealt with here or in previous (or future) posts on this topic: voter base, issue dimension and the degree of issue bundling

First, niche parties reject the traditional class-based orientation of politics. Instead of prioritizing economic demands, these parties politicize sets of issues which were previously outside the dimensions of party competition… [T]hese parties … challenge the content of political debate.

Second, the issues raised by the niche parties are not only novel, but they often do not coincide with existing lines of political division. Niche parties appeal to groups of voters that may cross-cut traditional partisan alignments.

Third, niche parties further differentiate themselves by limiting their issue appeals. They eschew the comprehensive policy platforms common to their mainstream party peers, instead adopting positions only on a restricted set of issues. Even as the number of issues covered in their manifestos has increased over the parties’ lifetimes, they have still been perceived as single issue parties by the voters. Unable to benefit from pre-existing partisan allegiances or the broad allure of comprehensive ideological positions, niche parties rely on the salience and attractiveness of their one policy stance for voter support. (Meguid 2005, 347-348)

Adams et al (2006) accept some of these restrictions but not all of them. Their definition focuses on ideology but rejects the need for a cross-cutting ideological dimension or the abandonment of class politics. Instead they accept as “niche” those

party families who present either an extreme ideology (such as Communist and extreme nationalist parties) or a noncentrist “niche” ideology ( i.e., the Greens). (Adams et al, 2006, 513, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3694232 .)

The key underlying factor for Adams et al thus appears to be some kind of distance from the dimensional segment defined by the main parties; niche parties are either in the same plane as the main competition but some distance from the nearest competitor on its side, or they are some distance away from the main dimension on a secondary or tertiary dimension. Graphically, the difference between Meguid and Adams et al looks something like this:

Removing the restrictions on the main dimension of competition/class-based appeals is significant. It minimizes the question of dimensionality, replacing it with proximity (“extreme”, “non-centrist”), and also eliminates Meguid’s demographic limitations that exclude class-based parties from the “niche” category.

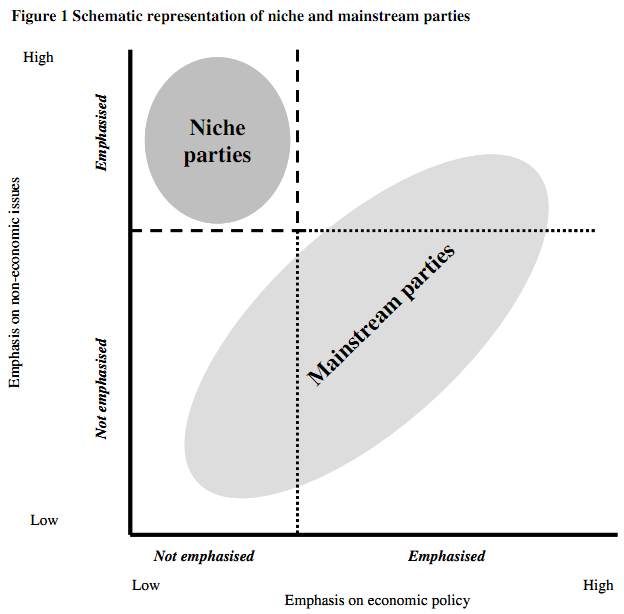

Wagner offers a simplified version of Meguid, defining “niche parties” as those “that de-emphasise economic concerns and stress a small range of non-economic issues”(2011, 3, http://homepage.univie.ac.at/markus.wagner/Paper_nicheparties.pdf)

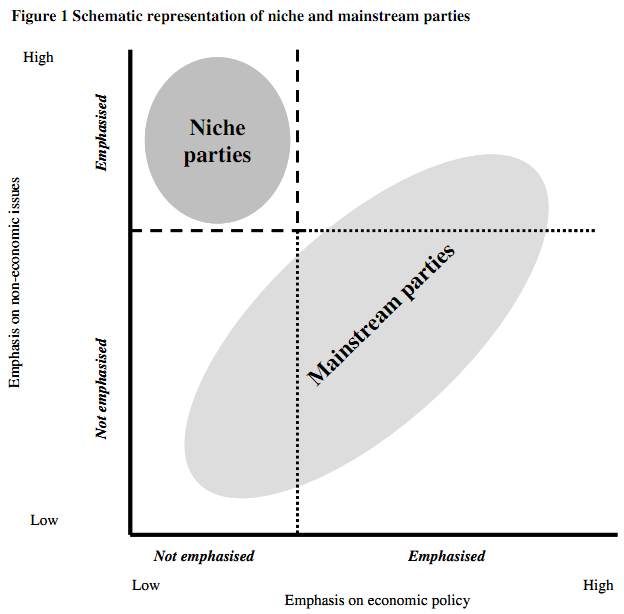

Wagner’s analysis lends itself to an elegant graph that defines niche parties in strictly economic terms and places in the mainstream any party that either emphasizes economic issues or avoids non-economic issues:

Wagner’s definition thus sets aside any notion of the demographic basis of class competition (potentially opening the door to Communist parties) but it also removes the degree of extremeness of a party’s position in favor of a pure reliance on emphasis (excluding Communist parties from a different direction). The simplification allows him to address and measure the “niche-ness” of specific parties rather than assuming it based on a party’s “family” which may for an individual party be a poor fit (Bresanelli 2011 finds a fairly large number of parties whose manifestos do not match well with those of others in their European Parliament group, with the share of such parties particularly high in postcommunist Europe, http://euce.org/eusa/2011/papers/6f_bressanelli.pdf). Wagner’s party-specific measure also accommodates changes over time to and from the “niche” category as parties pick raise or lower their economic and non-economic emphases. This more nuanced analysis has its limitations: Wagner establishes economic policy as the only dimension used for distinguishing mainstream from niche, and he establishes binary cut-off points for economic and non-emphasis. Even here, however, he suggests some flexibility: he acknowledges both the possibility of a scalar alternative to the binary cutoff points, and he suggests the possibility of a non-economic variant for “party systems in some countries are defined more strongly by, for example, ethnic divisions” (9)

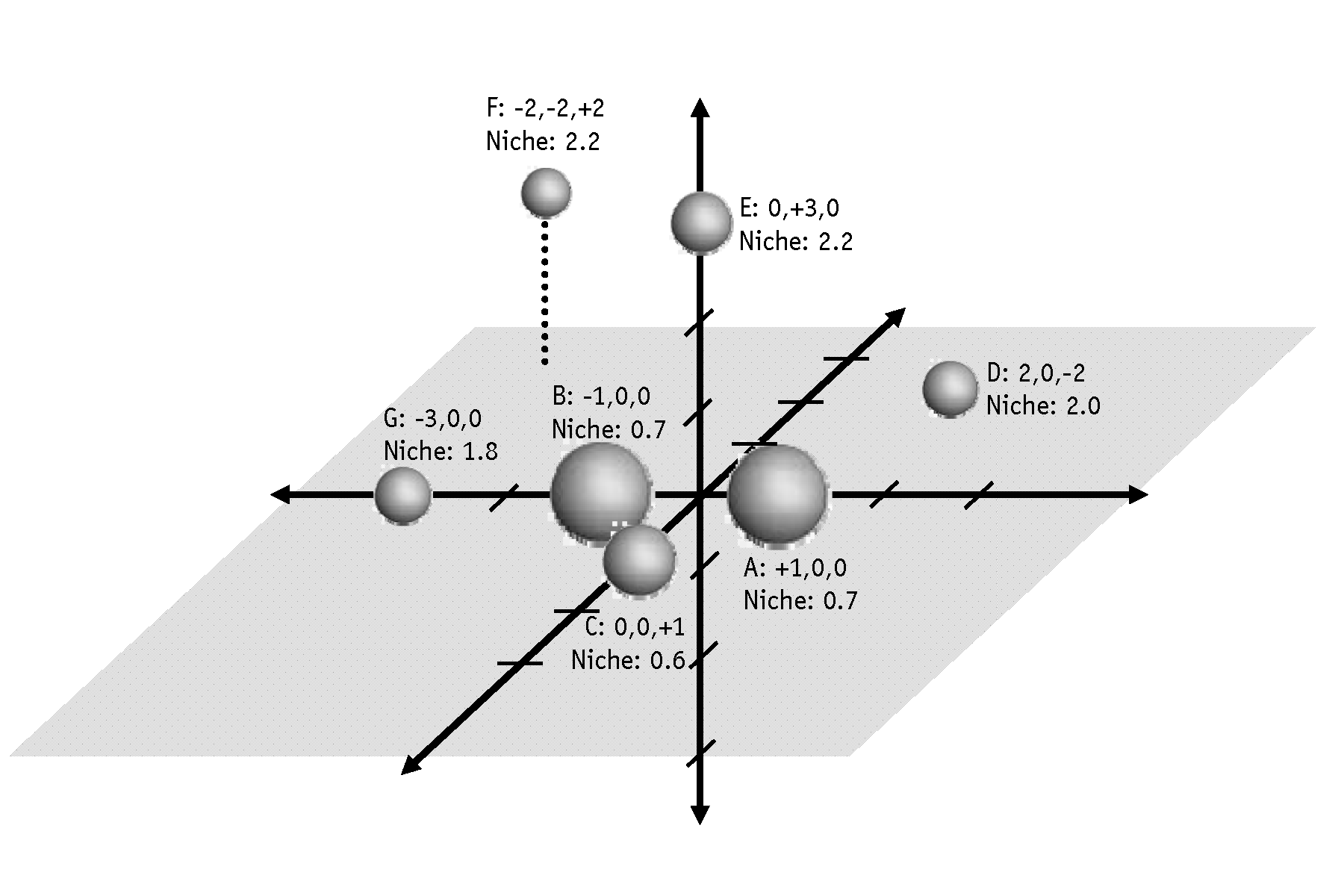

An even more recent piece by Miller and Meyer offer an alternative that strengthens Wagner at its weakest points: the binary distinction and the lack of attention to alternative dominant dimensions (2011, http://staatswissenschaft.univie.ac.at/uploads/media/Miller___Meyer_-_To_the_Core_of_the_Niche_Party.pdf). Miller and Meyer define “niche parties”as those that “compete by stressing other policies than their competitors“(4) or, according to another formulation in the paper, “A niche party emphasizes policies neglected by its rivals”(5). They operationalize this relatively simple definition with a measure that “compares a party’s policy profile with the (weighted) average of the remaining party system” across multiple dimensions (11). In the process they depart from Wagner’s use of the economic dimension as a baseline for “the mainstream”: “We conclude that – while economic niches might be rare – to exclude them by definition unnecessarily restricts the concept”(8). The formula also generates a scale which allows comparison of parties according to the “degree of nicheness.”

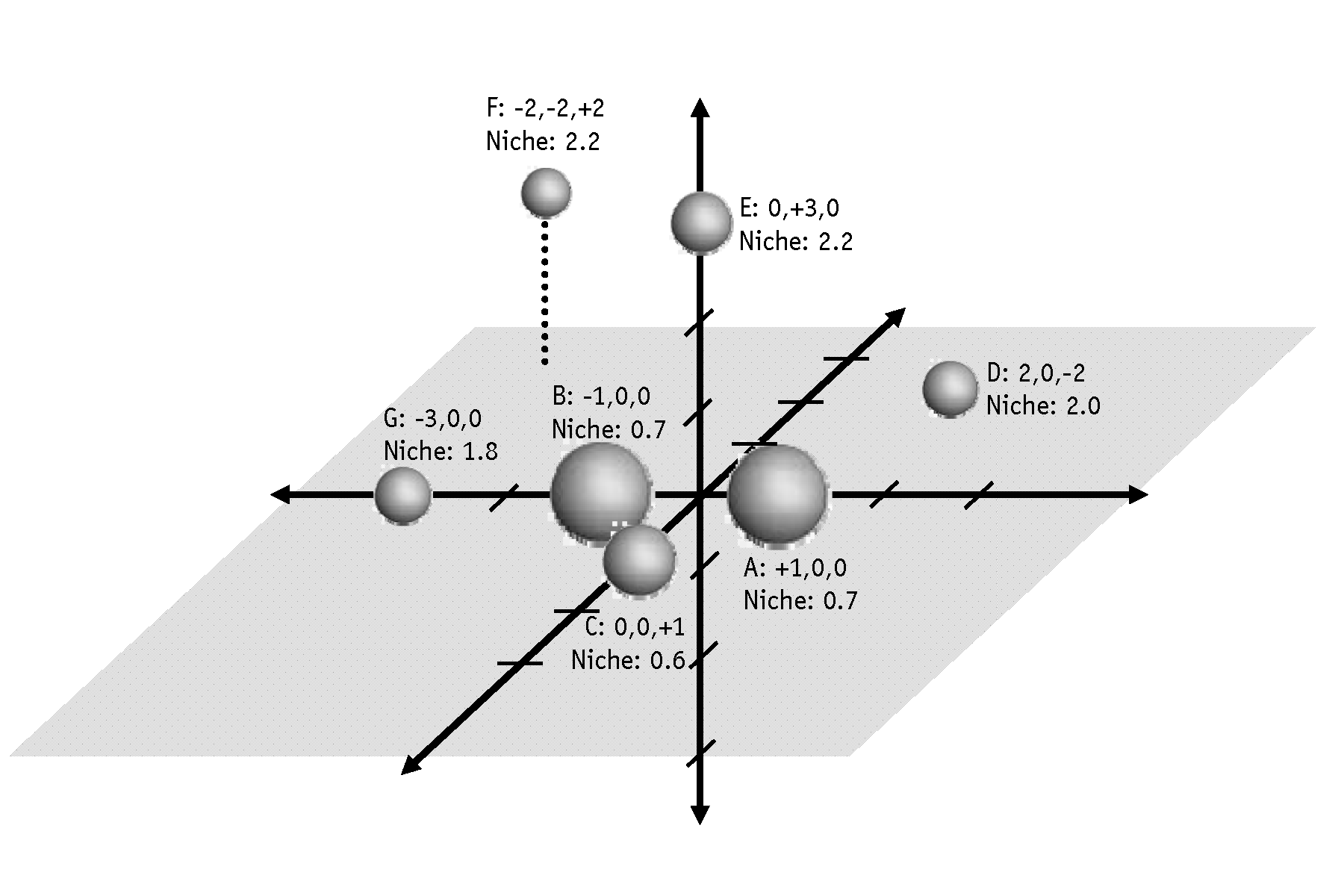

The formula is intuitive and easy to grasp. The farther a party is from all other parties on a given dimension–in terms of emphasis, it must be remembered, and not policy position–the higher is the niche score for its position on that dimension. The more niches its positions on a variety of issues, the more it can be considered a niche party. My first attempt to give a visual picture of how distances translate into niche positions is the spatial approach below:

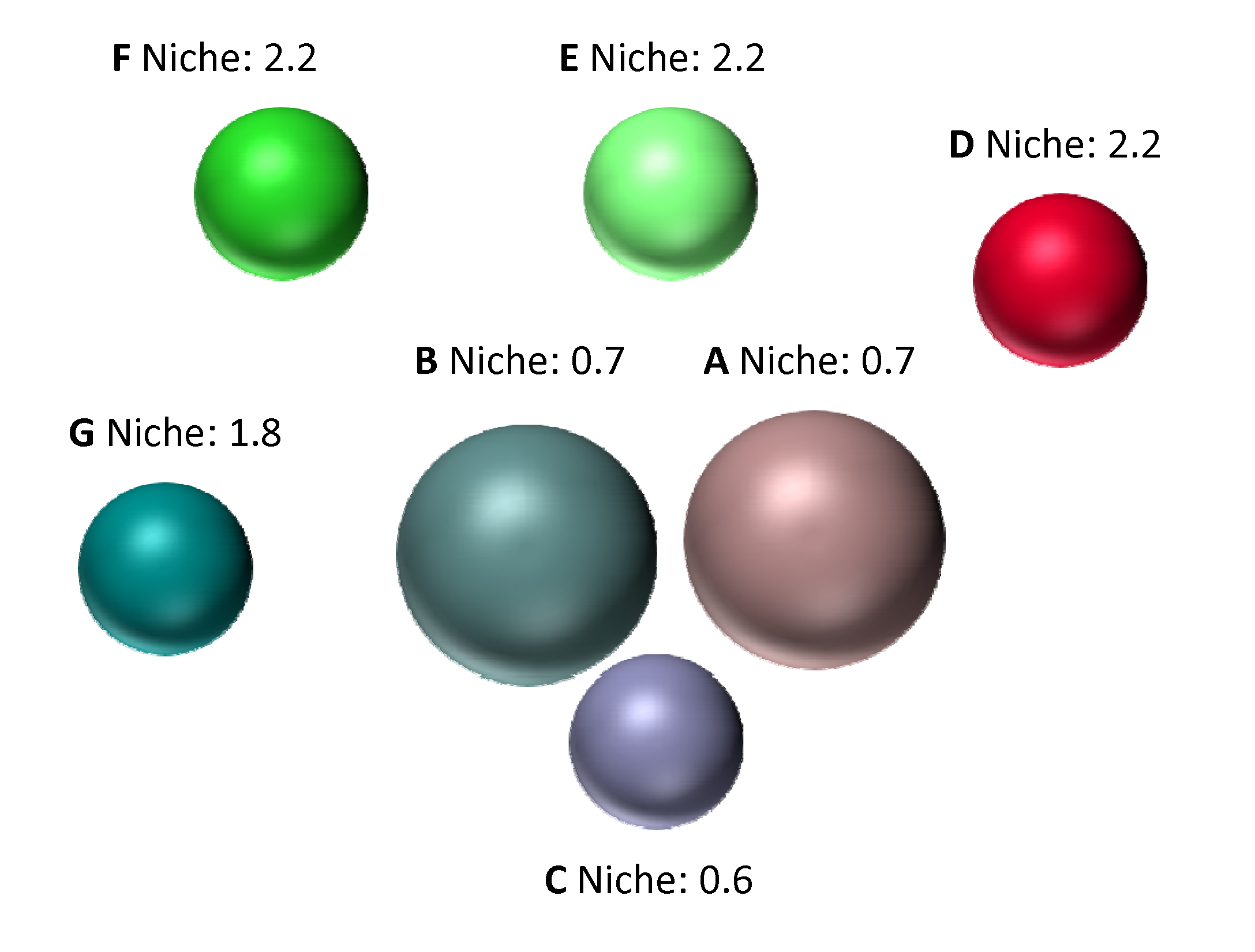

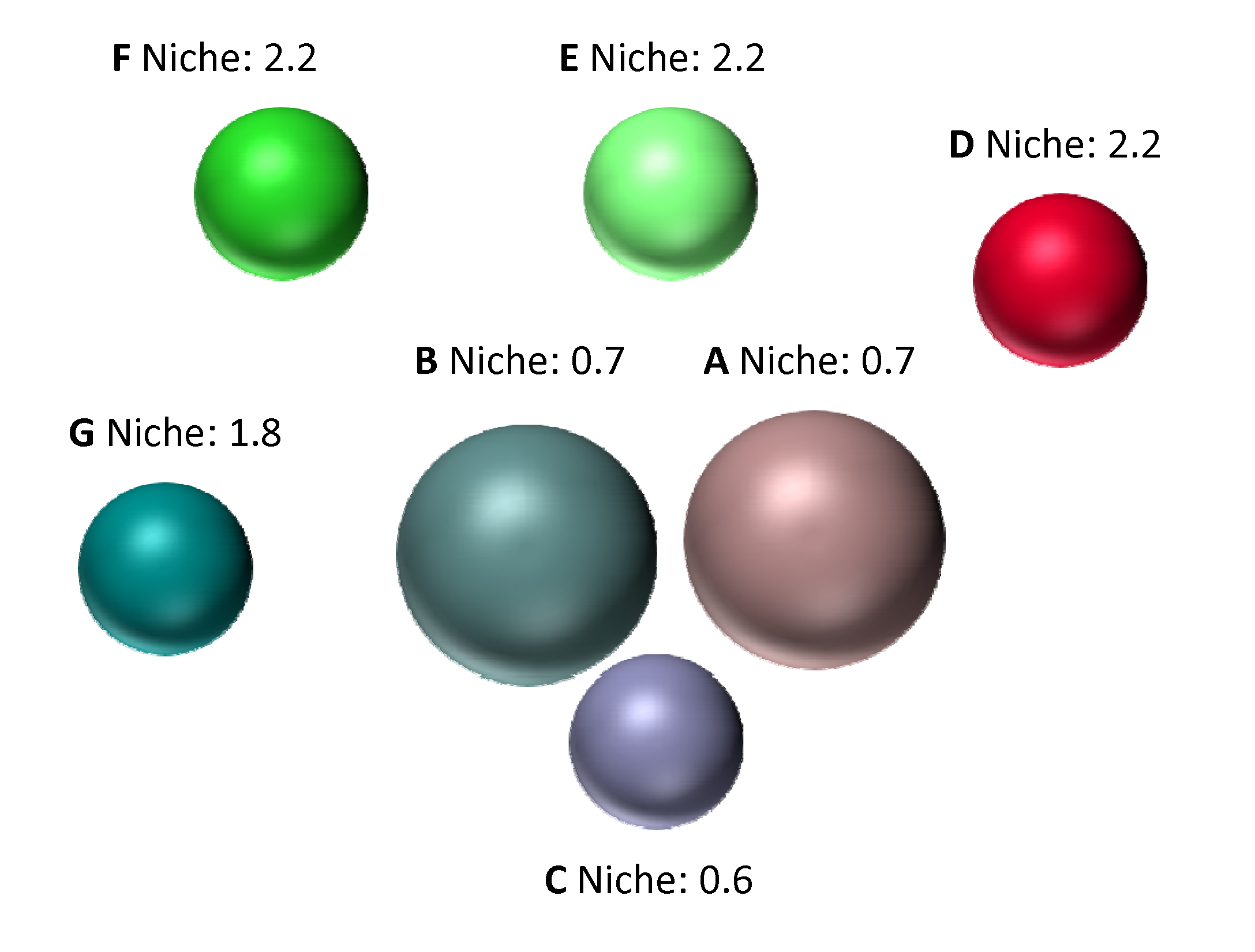

This is misleading,however, because we are used to reading these kinds of graphs as representing positions whereas in this case they represent intensities. It is therefore useful (and more fun) to reconceptualize the map in terms color, with each party’s emphasis translating into a score on 3 color dimensions: red, blue and green. In this case the intensity of color is roughly analogous to difference from the center (which would be flat grey). Bright in this case equals “nichy.”

This is misleading,however, because we are used to reading these kinds of graphs as representing positions whereas in this case they represent intensities. It is therefore useful (and more fun) to reconceptualize the map in terms color, with each party’s emphasis translating into a score on 3 color dimensions: red, blue and green. In this case the intensity of color is roughly analogous to difference from the center (which would be flat grey). Bright in this case equals “nichy.”

Party A and B occupy opposite positions on a single issue dimension (which could be taken here to be the “main” one except that this method does not identify a “main dimension”) and are low-emphasis on all the others. They thus have quite low niche scores and are quite grey. Party C’s niche score is even lower because it is likewise low-emphasis on all issues except one and (thanks to parties A, B and G, it is relatively close to the mean on that one issue. Parties D, E, F, and G all have unbalanced emphasis in their own way, either on one issue (E and G) or two (D) or all three (F) and are therefore brightly colored. It is noteworthy here that while starting closer to Meguid’s notion of dimensionality than to that of Adams et al, Miller and Meyer end up allowing niche status to parties on any dimension of competition as long as it sufficiently different from the emphasis of other parties.

Party A and B occupy opposite positions on a single issue dimension (which could be taken here to be the “main” one except that this method does not identify a “main dimension”) and are low-emphasis on all the others. They thus have quite low niche scores and are quite grey. Party C’s niche score is even lower because it is likewise low-emphasis on all issues except one and (thanks to parties A, B and G, it is relatively close to the mean on that one issue. Parties D, E, F, and G all have unbalanced emphasis in their own way, either on one issue (E and G) or two (D) or all three (F) and are therefore brightly colored. It is noteworthy here that while starting closer to Meguid’s notion of dimensionality than to that of Adams et al, Miller and Meyer end up allowing niche status to parties on any dimension of competition as long as it sufficiently different from the emphasis of other parties.

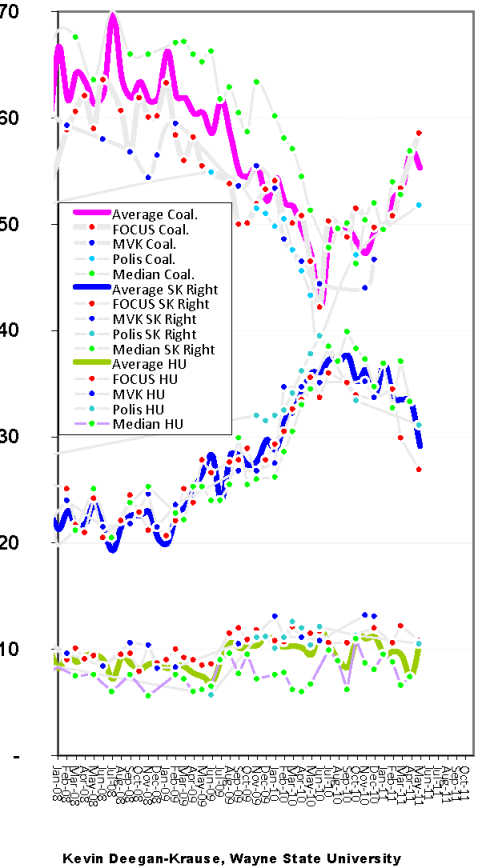

In practical use, this measure still exhibits a certain degree of awkwardness. In particular it appears to be highly sensitive to number and type of dimensions used for calculating the overall niche scores. Miller and Meyer use party manifesto data arranged in well-defined categories for Western Europe which appears to serve them well (I cannot judge at first glance), but for Eastern Europe where manifesto data is notoriously problematic, this method might not work as well (and it certainly depends in Miller and Meyer’s case on the not-always-accurate assumption that the sheer amount of verbiage translates into emphasis). The method should, in theory, be usable with expert survey data on the salience of issues for particular parties, but these vary substantially in terms of what “dimensions” they ask about. As a result, the results for “niche-ness” of particular parties can differ, even in relatively stable party systems. The two tables below present results of my preliminary calculations for the two countries I know better than others using the available expert survey data on emphasis. The results are extremely consistent for some parties and quite different for others, particularly those with some “niche” characteristics or others.

Table 1. Niche scores for parties in the Czech Republic based on Expert Surveys

| Party |

Expert Surveys |

Overall |

My own assessment |

| 2002 Eurequal |

2006 North Carolina |

2007 Eurequal (evaluated dimensions) |

2007 Eurequal (policy areas) |

| CSSD |

-0.2 |

-0.3 |

+0.1 |

-0.1 |

Mainstream through intermediate |

Mainstream |

| KDU-CSL |

+0.1 |

+.6 |

-0.2 |

+0.1 |

Mainstream through niche |

Interesting question |

| KSCM |

-0.1 |

+0.2 |

-0.1 |

+0.4 |

Intermediate through niche |

Interesting question |

| Nezavisli |

– |

-0.1 |

– |

– |

Intermediate |

|

| ODA |

+1.1 |

– |

– |

– |

High |

|

| ODS |

-0.3 |

+0.0 |

-0.0 |

-0.2 |

| Mainstream through intermediate |

|

Mainstream |

| SNK-ED |

– |

-0.8 |

– |

– |

Mainstream |

|

| SZ |

– |

-0.1 |

+0.5 |

+0.8 |

Intermediate to niche |

Interesting question |

| US |

+0.4 |

– |

– |

– |

Intermediate |

|

Table 2. Niche scores for parties in Slovakia based on Expert Surveys

| Party |

Expert Surveys |

Overall |

My own guess |

| 2002 Eurequal |

2006 North Carolina |

2007 Eurequal (evaluated dimensions) |

2007 Eurequal (policy areas) |

| ANO |

+0.7 |

– |

– |

– |

Niche |

|

| HZDS |

-0.4 |

-0.8 |

-0.5 |

-0.4 |

Mainstream |

Mainstream(at first) |

| KDH |

+1.1 |

+0.4 |

+0.6 |

+0.0 |

Intermediate through niche |

Intermediate through niche |

| KSS |

-0.0 |

+0.1 |

– |

– |

Intermediate |

Interesting question |

| PSNS |

-0.1 |

– |

– |

– |

Intermediate |

Interesting question |

| SDKU |

+0.1 |

+.01 |

+0.0 |

+0.5 |

Intermediate through niche |

Mainstream through intermediate |

| SF |

– |

-0.6 |

– |

– |

Mainstream |

|

| Smer |

-0.3 |

-0.5 |

+0.2 |

+0.2 |

Mainstream through intermediate |

Mainstream |

| SMK |

-.01 |

+0.7 |

+0.2 |

-0.1 |

Intermediate through niche |

Niche if there ever was one |

| SNS |

+0.2 |

+0.7 |

+0.0 |

-0.1 |

Intermediate through niche |

Interesting question |

Used here the method does a fairly good job identifying parties that are clearly mainstream by any reckoning–the Czech ODS and CSSD and the Slovak Smer–but for other parties there is significant disagreement, and many of the parties producing the sharpest disagreements are those that defy easy non-quantitative categorization.

- Green parties: The Green party would be considered “niche” by both Meguid and Adams et al and falls into that categorization in both measures of the 2007 Eurequal survey but not in the 2006 North Carolina survey, in large part because the North Carolina survey simply does not have a measurement of environmental questions and so its niche-ness comes out only on lifestyle and ethnic minority questions.

- Communist parties. Both the Slovak and Czech communist parties (the unreconstructed ones rather than their social democratic successor parties) emerge as slightly but not overwhelmingly more niche-like than other parties. That such parties are an open question corresponds well with the disagreement between Meguid and Adams et al about whether to include them in the niche category.

- Christian Democratic parties. While not included in either Meguid or Adams categories, such parties in postcommunist Europe (and in certain parts of Western Europe, particularly Scandinavia) often appear to operate by many of the principles specified by Meguid: avoiding class based appeals (they did this from early on), taking up issues off the main issue dimension (church and morality issues are not the main dimension in most of these countries), and keeping a relatively narrow range of issues, though they did at least claim to take positions across all of the major issue areas. Both the Slovak and Czech Christian Democrats put a foot in the niche category and in the 2002 survey Slovakia’s Christian Democratic Movement receives the highest niche score of any party in the survey. At the same time it (and its Czech counterpart) show few niche qualities at all in the 2007 Eurequal survey long version, because their distinctive stands on lifestyle issues are diluted by an extremely large number of economy-related questions in the survey.

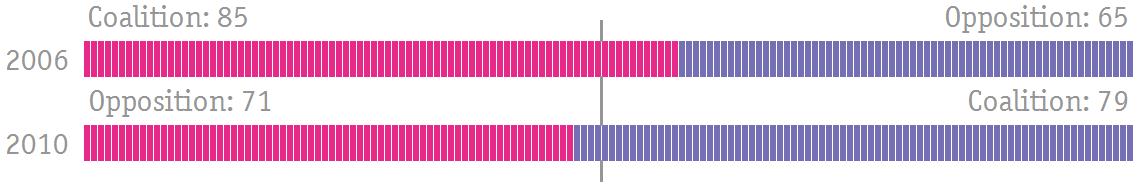

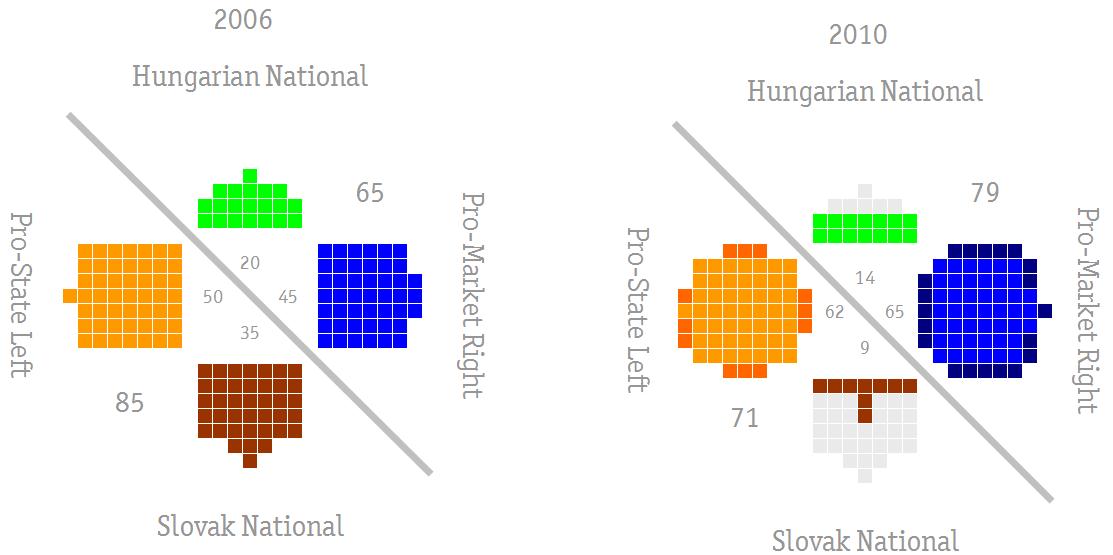

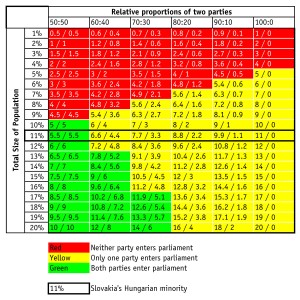

- Ethnic minority parties. Slovakia brings three additional parties into the niche debate, all of which made strong ethnic-based appeals. The most clearly niche-like party of these three–indeed perhaps of all the parties listed in the two tables above–is SMK (the Party of the Hungarian Coalition)–a party with an almost purely ethnic Hungarian voting base and no major policy issues beyond minority rights and related issues. Yet this party produces a high niche score only in the 2006 North Carolina survey which has three questions (out of a total of twelve) on nationalism, ethnic minorities, and decentralization. The same survey suggests an equally high niche score for the SNS (the Slovak National Party) which takes diametrically opposed but equally emphatic positions on the same issues.

- Liberal parties. Finally, there is the question of liberal parties. These are often small parties, sometimes with relatively narrow issue emphases, but because in Western Europe they tend to compete on the main issue dimensions, they rarely fall into the niche category and are not included either by Meguid or Adams. In Slovakia and the Czech Republic, however, they often appear to fall into this category. The Czech party US (Freedom Union) received a positive niche score in because of its position on social rights (matched and countered by its election coalition partner, the Christian Democrats) and another liberal party, ODA received one of the highest niche scores on the 2002 Eurequal survey (though largely because the party was by then moribund and received low salience scores on nearly every question. In Slovakia, one small liberal party returned extremely mainstream scores (SF, Free Forum) but two others returned scores that were mixed on the niche side (SDKU, the Slovak Democratic and Christian Union) or strongly niche-like (ANO, the Alliance of the New Citizen) on the basis of social rights questions which in Slovakia (as in the Czech Republic) are not a high salience issue when compared to others.

Even if this application of Miller and Meyer’s formula in this form and with this data does not (yet) provide a fully reliable measure, their standard for measuring niche parties does gets at the key issues of “niche-ness” in Central Europe and helps us think more clearly about politics in the region.

Meguid took a helpful first step with her attention to secondary and tertiary issue dimensions, and Wagner and Miller and Meyer add a useful emphasis on issue salience that edges into areas of issue ownership. One way to think about what politics is “about” in a particular country is to look at what the main political forces fight about and what other political forces “fight to fight about” turning political debate onto some other topic where they are strongest. From Schattschneider and Riker through contemporary scholars such as Green-Pedersen, there has been a strong current of emphasis on the meta-struggle about the issues over which we struggle. In this sense we might regard niche parties simply as those that achieve limited success in the herasthetic realm. They neither fail so badly that they gain no voters nor succeed so well that their issue dimension becomes the dominant one. Or (since according to Miller and Meyer this sort of “niche-ness” is not static), they may be simply passing through from one of these extremes to another. Niche parties thus call our attention to the partial dimensions that surround the main conflict, the asymmetrical battles between one party and all the rest. They can be characterized as positional conflicts between two rival policies, but it may be better to characterize them as conflicts of attention between parties that do not care and parties that do. So it is little surprise (in retrospect) that such parties behave differently from others since their struggle is not to attract voters to a position but rather to attract voters’ attention to that position and hold it there.

In a sense it could be argued that all parties seek to do this, even on main dimensions. So called mainstream parties seek out the niches within the main stream as they try to attract attention to a specific aspect of the issue where they hold the advantage: Party A’s reputation for lowering taxes versus Party B’s reputation for improving services (Colomer and Puglisi 2005). It is not clear to me whether this is qualitatively different from the kind of effort undertaken by niche parties, but it does seem different to the extent that the two issues are bound up in the minds of voters: if lowering taxes and improving services are inextricably linked in most voters’ minds, then Party A’s appeals to its own area of strength cannot but cast some attention to the rival strength of Party B. It may be for this reason that a considerable part of party effort may be in this linking or de-linking of issues to one another. If Party A can argue successfully that the level of taxation has nothing to do with the quality of service, then it can create for itself a “niche”–and because it is a niche within the main stream of political life, where voters are already passionate and attentive, it may hold the key to political majority. For less-discussed, less-salient issues, an equally persuasive effort at projecting issue ownership will net fewer voters and so niches outside of the mainstream, and so such a party must expend its effort not only to persuade that its position is right, and not only that it is the best party to advance that position, but also that the position matters in the first place. So we should expect niche parties to be different from other parties.

But perhaps by the same token we should expect niche parties to be different from one another, because some of these partial dimensions, secondary and tertiary dimensions may have fundamentally different characteristics from others. And here it is necessary to raise the slippery question of demographics. Demographic characteristics are admittedly less solid than they look. Questions on public opinion surveys separate respondents into rigid, well-defined categories that seem relatively permanent but even once solid fixtures like class and religion are now in seemingly permanent definitional flux, and as with attitudes, the role of demography in political decision-making depends not only on an individual’s characteristics but on the salience of those characteristics in political struggle. And salience is not the only fluctuating element. A key element of demographic (and attitudinal) determinants of politics is the sense of mutual-recognition and groupness among those who share them. These are often overlooked (perhaps because they are not easily quantified) but play a major role in shaping their importance. Political decisions are not always made by individuals who participate in groups; they sometimes emerge within groups and capture the allegiance of the individuals involved. That allegiance, like the demographic characteristics themselves, may be sticky, and may produce fairly high barriers between “in” and “out.” And here, finally, is where niche parties come in. Those whose partial issue dimensions depend on individual sentiment and loose attitudinal configurations should behave quite differently from those that stem from hard-to-change characteristics and mutually reinforcing social circles. Both must constantly fight for the salience of their chief position; only some will do so by encouraging group identity and interconnection.

It is this latter consideration that now causes me to wonder a bit about the wonderful work by Meguid, Wagner and Miller and Meyer. In one sense it exactly what we need: serious research about partial dimensions and their empirical dimensions and dynamics. In another sense, though, it may be a misnomer to talk about this in terms of “niches.” I am struck by a passage of Miller and Meyer which notes that “Niche parties do not have their nicheness carved in stone”(2011, 8) and the contrast between this interpretation and the original meaning of niche which was by definition something carved in stone. Of course etymology is not destiny, but there is something relevant about the carved-in-stone-ness of certain party positions. Niche parties may all shift political competition to questions more relevant to their own programmatic strength, but there is a fundamental difference between greens and majority nationalists on the one hand and ethnic or religious minorities on the other. The latter come as close as possible to the architectural metaphor of a niche: the recesses are deep and the walls around them quite thick and hard-to-penetrate. Of course the same can also be said for some Communist Parties, which may explain their inclusion in the work of Adams et al. Compared to these, majority nationalists or greens or cultural liberals (in Central and Eastern Europe at least) do not fit the same profile, do not face the same advantages in holding a well-defined voting base or the same difficulties in trying to expand.

This analysis suggests two different dimensions, producing three categories of niche party:

|

Issue Centrality |

Primary

Dimension,

Full |

Secondary/Tertiary Dimension,

Partial |

| Group closure |

Low |

Social Democrats Conservatives

Liberals |

Greens

Majority nationalists

Some social liberals |

| High |

Communists

Some Christian democrats |

Ethnic minorities

Religious minorities

Some Christian democrats |

Some parties qualify as niche by either standard–they have both a high degree of group closure and a non-central issue. Of the remainder, some exhibit only collectivity or identity niches but remain on the central dimension of competition, while other occupy (potentially less enduring) issue niches without a sense of group identity or commonality beyond the issue at hand.

This question needs more work that is not strictly relevant for my immediate purpose, so I will come back to it in future posts. In the meantime, this discussion of niche parties leads directly into the last two topics I want to discuss in this “work in progress” series: issue salience and ownership and parties’ demographic and collective ties. But more on those in a few days.

riend of a friend is seeking good idiomatic Slovak translations for several political terms–“Spin” “Passing the Buck” and “Doublethink” and this seems to be an ideal task for the readers of this blog. Just leave your suggestions in the comment space below. Thanks in advance!

riend of a friend is seeking good idiomatic Slovak translations for several political terms–“Spin” “Passing the Buck” and “Doublethink” and this seems to be an ideal task for the readers of this blog. Just leave your suggestions in the comment space below. Thanks in advance!