Sample Papers

The following papers are good examples of student papers that are well-organized, concisely written, and thoroughly researched. They may help you get a sense of what I look for in a good paper. Many thanks to Suzanne Hassan, Robert Mahu and Gergana Sivrieva for their permission to reprint them here in pdf format and below:

Sample 1. Executives-Parties Dimension: Spain

1. Introduction

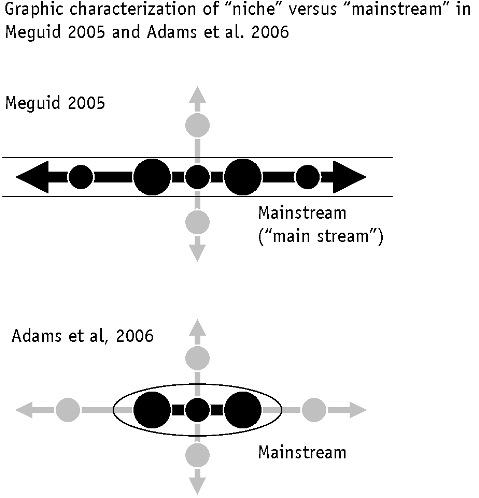

The death of Francisco Franco and subsequent political developments ushered in Spain’s transition to democracy—a democracy that has since institutionalized. The sustainability of Spain’s democratic government clear but what type of democracy has emerged? There were certainly elements of both the majoritarianism and the consensual model of democracy present throughout the transition; however, an analysis of the five categories in Arend Lijphart’s executives-parties dimension in relation to Spain’s institutions shows that a shift occurred from a consensus to a majoritarian democracy[1], and that this change is relatively disadvantageous. Currently, Spain has a disproportional electoral system, a history of alternating single-party majority or minority administrations, single-party cabinets, greater executive dominance, and relatively pluralist interest groups.

2. Describing Spain’s model

Prior to delving into the categories, an explanation of the majoritarianism-consensus contrast is pertinent. The core of the majoritarian model of democracy is that it is based upon the majority rule of a country’s citizens. In contrast, the consensus model takes into account as broad of range of opinions as possible and does not limit itself to the wants and needs of the majority. Lijphart further describes the differences between the two by stating “the majoritarian model of democracy is exclusive, competitive, and adversarial, whereas the consensus model is characterized by inclusiveness, bargaining, and compromise” (Lijphart 2012, p. 2).

2a. Majoritarian and disproportional electoral systems versus proportional representation

Shortly after the death of dictator Francisco Franco, there was a nearly universal consensus on the need to reach a peaceful transition through a fair and reliable election with an electoral system that would be equipped to provide the opportunity for a wide political spectrum to compete for representation in future parliament (Sosa Clavel 2010). The subsequent design of the Spanish electoral system created proportional representation (PR); however, the manner in which voting power is allocated among the Spanish provinces demonstrates that the PR label is deceptive (Lijphart 2012, p. 133-135). Spain uses a closed-list system to elect the Congreso, meaning that voters can only vote for a political party, not a particular candidate. In addition, the system uses the d’Hondt formula, “which has a slight bias in favor of large parties and against small parties” (Lijphart 2012, p. 135). Elections to the 350 member Congreso are organized by province. The 50 historic provinces (plus Ceuta and Melilla) that were chosen as the electoral districts, did not account for subsequent demographic changes (Hopkin 2006, Oxford Scholarship Online). Consequently, the provinces are not represented in proportion to their population, and there is a tendency for the overrepresentation of rural and less-populated provinces since each is guaranteed two seats in the Congreso. The remaining seats are allocated proportionally to population. The median number of seats per province is only five, which is a relatively small number per constituency, and the limited number of seats available for the large number of constituencies makes the existence of high proportionality difficult (Hopkin 2000, p. 6 and Rush 2007, p. 716). Spain’s “apportionment scheme, coupled with the party list system and the d’Hondt electoral formula favors larger political parties with nationwide appeal. As a result, the electoral system has diminished the number of effective political parties contesting elections and makes it easier for larger parties to govern without seeking coalition partners” (Rush 2007, p. 716).

2b. Two-party versus multiparty system

The post-Francoist Spanish state has always had a multiparty system; however, the “impure PR system” described above (Lijphart 2012, p. 157) has influenced the development of a relatively stable single-party governing majority over time. The pre-1982 system was composed of two large parties both potentially capable of governing (Union of Democratic Center; UCD and Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party; PSOE) along with two smaller and more extreme parties (People’s Alliance; AP and the Communist Party of Spain; PCE). The presence of four relevant parties made a single-party majority unlikely and necessitated the formation of coalitions. Thus, Spain’s system could be described as moderate pluralism (Hopkin 2000, p. 5). After 1982, the disappearance of UCD allowed the PSOE to take control of the pivotal center space in the party system, while the decline of PCE reduced threats from the left. Thus, the previous balance among parties was overturned and the PSOE acquired a sustainable single-party governing majority (Hopkin 2000, p. 5). Balance reemerged in the system in 1993 when the Socialists’ power began to decline and the People’s Party (PP) emerged as a governing rival (Hopkin 2005, p. 13).

The Spanish party system has therefore developed into what could be described as an ‘adulterated’ two-party system. Despite the quite high a number of parties represented in parliament, the party system essentially revolves around a bipolar competition between the two large statewide parties. The strong presence of non-statewide parties, and the nature of the electoral system, place obstacles in the way of the winning party achieving an overall majority. However, the post-1982 pattern of alternating single party majority or minority administrations places Spain closer to the majoritarian than to the consensual end of the scale (Hopkin 2005, p. 13-14).

2c. Concentration of executive power in single party majority cabinet versus executive power sharing in broad multiparty coalitions

The formation of the cabinet is derivative of the electoral system and the party size. In Spain, the two large parties have occupied the Executive, which has lead to the formation of single-party cabinets whether supported by a relative or absolute majority in the legislature (Ajenjo and Molina 2007, p. 5). Thus, although “democracy has now existed in Spain for over 30 years, […] in that time none of its 11 legislative terms has produced a coalition government” (Falcó-Gimeno 2012, p. 487). Nevertheless, some have argued that Spain’s democratic cabinet initially belonged to the consensus category. Although the UCD governments of 1977-82 were not formal coalitions, the party itself originated as a coalition. Further, since the UCD was a minority administration, inter-party agreements were made to enable laws to be passed (Hopkin 2000, p. 3-4). Currently, the electoral system (which is formally proportional, but more majoritarian in practice) has systematically produced stable single-party governments—further support for the shift to majoritarianism. (Ajenjo and Molina 2007, p. 18 and Lijphart 2012, p. 126).

2d. Executive-legislative relationships in which the executive is dominant versus executive-legislative balance of power

Lijphart states that, “countries that have more minimal winning single-party cabinets also tend to be the countries with greater executive dominance” (Lijphart 2012, p. 124) This fits the case of Spain, which has an index value of executive dominance of 8.26, a little higher than the United Kingdom’s value of 8.12 (Lijphart 2012, p. 121). The constitutional framework that manages the executive-legislative relationship has instituted executive dominance over parliament both under the Francoist state and also under the democratic constitution of 1978. That being said, the executive-legislative relationship was considerably balanced between 1977 and 1982 and then shifted to clear executive domination since 1982 (Hopkin 2000, p. 4-5). The primary objective of Suarez, the fist democratically elected Prime Minister, was to pass a constitution with overwhelming support of the parliament. Consequently, he subordinated partisan interests. Thus, the parliament had the power to veto certain government proposals (Hopkins 2005, p. 9-10 and Hopkin 2000, p. 4-5). After 1982, parliamentary majorities allowed executive dominance, putting parliament into a subordinate role and permitting an increase in partisanship (Hopkins 2005, p. 10).

2e. Pluralist interest groups with free for all competition among groups versus coordinated and corporatist interest group systems aimed at compromise and concentration

The final category of the executives-parties dimension concerns interest groups. According to Lijphart’s index of interest group pluralism, Spain scores a 3.04, which reflects a high degree of pluralism (Lijphart 2012, p. 164-166). Pluralism means “a multiplicity of interest groups that exert pressure on the government in an uncoordinated and competitive manner” (Lijphart 2012, p. 16). In contrast, interest group corporatism, also referred to as concertation, refers to a process of coordination between representatives of government, labor unions, and employers’ organizations (Lijphart 2012, p. 16). Other studies show that “some degree of concertation was achieved during the UCD governments, fell away during the PSOE governments, and has timidly reemerged” (Hopkin 2000, p. 6).

3. Disadvantages of the majoritarian model

After the analysis of Spain’s institutions in regard to each category in the dimension, it is important to focus on why the majoritarian model could be considered relatively disadvantageous to the operation of a democracy. First, the majority and plurality methods require that the candidate supported by the greatest number of voters is the one to win. While this can be interpreted as a fulfillment of the democratic ideal of “government by and for the people,” all other voters remain unrepresented. In contrast, proportional representation ensures that minorities also get a chance to be represented in parliament. Next, two-party systems certainly have some benefits. For example, they offer a clearer choice between two alternative ideologies and they lead to the formation of single party cabinets that are stable and effective at passing policies. Lijphart, however, argues that concentrated power does not always yield effective policymaking. Regarding the cabinet formation of a democracy, a coalition government could lead to instability due to the greater number of ideologies present in the legislature, but it can also lead to broader representation that can benefit a larger proportion of individuals. Multiple party cabinets also have the advantage of being able to add weight to certain issues that could otherwise be dismissed. Next, executive dominance over the legislature could lead to a leader who is entitled to rule as he or she sees fit, constrained only by a constitutionally limited term of office. A more balanced relationship between the executive and the legislative branches could ensure collegiality in decision-making. Lastly, corporatism removes the winner-take-all mentality and promotes social partnership within interest groups. The regular meetings between the three major groups lead to comprehensive agreements that are binding on all parties. Thus, Lijphart purports that “consensus democracies have a superior record with regard to effective policy making and the quality of democracy compared with majoritarian democracies” (Lijphart 2012, p. ix).

Bibliography

- Falcó-Gimeno, Albert. “Preferences for Political Coalitions in Spain.” South European Society and Politics. 17.3 (2012): 487-502.

- Hopkin, Jonathan. “From consensus to competition: The changing nature of democracy in the Spanish transition.” The Politics of Contemporary Spain. Ed. Sebastian Balfour. New York: Routledge, 2005. 6-23.

- Hopkin, Jonathan. “From Consensus to Competition: Changing Conceptions of Democracy in the Spanish Transition.” University of Birmingham. (2000): 1-28.

- Hopkin, Jonathan. “Spain: Proportional Representation with Majoritarian Outcomes.” Oxford Scholarship Online. (2006). Available at <http://www.oxfordscholarship.com/view/10.1093/0199257566.001.0001/acprof-9780199257560-chapter-18>.

- Lijphart, Arend. Patterns of Democracy. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012. Print.

- Rush, Mark. “Voting Power in Federal Systems: Spain as a Case Study.” Political Science & Politics. 40.4 (2007): 715-720.

- Sosa Clavel, Andrés. “The Spanish Electoral System.” Mundo Electoral. 3.7 (2010). Available at <http://www.mundoelectoral.com/html/index.php?id=443>.[1] This change is present only for the executives-parties dimension. The federal-unitary dimension, experienced a movement that was more gradual and in the opposite direction (Hopkins 2000, p. 3).

Sample 2. Response to “Marxism is the best idea that has never been tried.”

Some scholars contend that “Marxism is the best idea that has never been tried”. However, if one allows for revisions to basic Marxist ideology, it is clear that Marxism was put into practice and that in many ways it was found lacking. The USSR and the socialist countries of Central and Eastern Europe illustrate the existence of Marxist-based systems in recent history. In order to determine whether Marxist systems existed in these countries, one must examine the basic tenets of Marxism, the extent to which the USSR and the socialist countries of Eastern and Central Europe followed and deviated from Marxism, and the causes of this deviation. Upon examining each of these characteristics, it is clear that, while flaws in Marxism resulted in the perpetuation of a ruling class, members of this ruling class did implement some form of Marxist ideology in their countries. Although systems based on Marxism existed, these systems failed because Marxist ideology itself is flawed and contradictory.

An examination of the fundamental concepts of Marxism is essential to determine whether the USSR and the countries of East-Central Europe implemented Marxism. At the center of Marxism is the notion of dialectical materialism. According to Marx, “the history of all past society has consisted in the development of class antagonisms” (1848, p. 14). In terms of dialectical materialism, these class antagonisms or struggles have taken a similar form – that of a thesis against an antithesis, which later combine to form a synthesis. The first class struggle arose within primitive communism as methods for acquiring wealth emerged, and other class struggles arose after this throughout history (Marx, 1848). Marx (1848) predicted that a revolution between the proletariat, or working class, and the bourgeoisie, or the owners of the means of production, would ultimately occur. Furthermore, according to Marxism, this would be the last class struggle because once the proletariat obtains ownership of the means of production there will be an abolition of class, and therefore, of class struggles (Marx, 1848). However, Marx did not take into account the perpetuation of a new class. Herein lies the flaw that allowed for the misuse of Marxist ideology by the leaders of the USSR and East-Central Europe.

Marxist ideology also examines the characteristics of the Revolution and of a Marxist-based society. Marx (1848) believed that the Revolution would occur quickly, in a country with a well-developed proletariat, such as Germany or France. Furthermore, “…the proletariat will use its political supremacy to wrest, by degree, all capital from the bourgeoisie, to centralize all instruments of production in the hands of the state, i.e., of the proletariat organized as the ruling class…” (Marx, 1848, p. 14). After the proletariat takes over the means of production, there should be implementation of certain changes in society, such as a heavy income tax and the abolition of property and inheritance (Marx, 1848). Other changes include the centralization of credit in banks, as well as of the means of communication and transportation, the combination of agriculture and manufacturing, free universal education, shorter workdays and an egalitarian society (Marx, 1848). However, the fact that a ruling authority or class must govern a centralized economy illustrates the contradiction in Marxism – the creation of a ruling class in order to ensure a classless society. Another important aspect of Marxism is the supremacy of the proletariat’s struggle over the appeals of nationalism. Marx’s (1848) call of “[p]roletarians of all countries, unite” illustrates his wish to abandon nationalist differences in favor of a unified class struggle against the bourgeoisie. However, the ruling class that emerged because of a flaw in Marxist ideology also used a form of nationalism to retain their power.

The fact that Marxism existed in the USSR belies the notion the Marxism “has never been tried.” The Bolsheviks, under Lenin, invoked Marxism in the Revolution of 1917 – albeit with some revisions. Immediately after the Revolution, numerous decrees, such as the Peace and Land decrees, made life somewhat easier for workers by shortening the workday and creating a more egalitarian society (Dziewanowski, 1996). Furthermore, the Bolsheviks established a radical socialist economy by using central planning that controlled all economic activity, including the seizure of all banks and means of communication (Dziewanowski, 1996). In this respect, the new leaders of the Soviet Union closely followed Marx’s recommendations concerning the characteristics of a Marxist society. Later, Stalin pushed for the collectivization of agriculture. This included the creation of two types of farms: collective farms, with pooled land and equipment; and state farms, where the farmers were employees of the state (Mason, 1996). The ideology of the transition period in the Soviet Union reflected Marxist ideology largely in respect to its “millenarian” outlook. This outlook propelled many people to work extremely hard in order to build their “worker’s paradise” (Espar & Jones, 1998). It is important to note that Stalin’s manipulation of Marxism forced the complete obedience of the public at all times. For example, Stalin claimed that Marxism is perfect and provides answers to everything (Schöpflin, 1993). Furthermore, Stalin proclaimed that problems arose not from the ideology, but from people who deviate from this ideology (Schöpflin, 1993). The population lived in constant fear of appearing to digress from Stalin’s interpretation of Marxism. Therefore, Stalin used Marxist ideology to maintain and expand his power in both the Soviet Union and in most of the socialist countries in Central and Eastern Europe.

While the leaders of the USSR followed many of the basic principles of Marxist ideology, these leaders also deviated from this ideology. In this respect, it is important to point out that Lenin made significant modifications to Marx’s theory of the Revolution. Lenin rejected the Marxist concept of a two-step revolution, instead calling for an immediate seizure of power by the Bolsheviks (Dziewanowski, 1996). Lenin (1902) also rejected the notion that the Revolution can only occur in a highly industrialized country. He felt that the peasants could work with the industrial proletariat to overthrow the Bourgeoisie. In addition, Lenin (1902) believed that a highly centralized group of trained revolutionaries must lead the effort to overthrow the bourgeoisie. Other early deviations from Marxism occurred during the New Economic Plan, which allowed peasants to sell agricultural goods for profit (Dziewanowski, 1996). It is important to note that these deviations were short-lived, in that Soviet leaders implemented them in order to create a basis for their legitimacy and maintain power. Later in the transition and consolidation phases within the USSR, leaders created a society that adhered closely to Marxist ideology, including central planning of the economy and the collectivization of agriculture.

The existence of socialist countries in Central and Eastern Europe also casts doubt on the contention that there has never been a system based on Marxist ideology. Because of the nature of the transition to socialism in Central and Eastern Europe, the countries in this region had economies and political systems similar to the Soviet Union. For example, “the new governments… seized most of the large landed estates and redistributed the property to ordinary peasants and farmers” (Mason, 1996, p. 14). Furthermore, the new socialist governments in East-Central Europe pursued other policies in line with Marxist ideology, such as subsidies on housing, education, medical care, and guaranteed employment (Mason, 1996). The collectivization of agriculture following the Soviet pattern also follows Marxist principles (Mason, 1996). Thus, in many important respects, the socialist countries of Central and Eastern Europe adhered to the principles of Marxism. However, it is important to note that Stalin and other Soviet leaders did not allow for much deviation from the Soviet model in order to maintain Soviet hegemony in the region.

Yugoslavia is a unique case study with respect to the implementation of Marxist ideology. Under Tito, Yugoslav leaders followed their own “separate road to socialism” (Mason, 1996, p. 21). In many respects, Marxist principles formed more of a basis of this different path in Yugoslavia than the economic plan set forth by the Soviet Union. For example, the very basis of Marxist ideology is worker control over the means of production (Marx, 1848). In contrast to the heavy centralization of the Soviet economy, Tito sought to decentralize the economy and create a system of “worker self-management of enterprises” (Mason, 1996, p. 21). In this respect, Tito and the Yugoslav path to socialism was much more in keeping of Marxist ideology than the Soviet Union. The fact that Tito was able to stray from the path put forth by the Soviet Union is also unique. Tito was one of the few communist leaders in East-Central Europe that came to power without Soviet intervention because he led the forces that defeated the Nazis in Yugoslavia. Although Tito had an indigenous basis for power, the overall result remains the same – Tito and the Yugoslav communists remained a ruling or upper class in their country. This illustrates that contradictions in Marxism resulted, not in a classless society, but in a society ruled by a select group.

The socialist countries of Central and Eastern Europe deviated from Marxist ideology as well. Perhaps the first of these deviations emerged with Tito’s separate road to socialism as discussed above. In this plan, Tito also called for a mixed-market economy (Mason, 1996, p. 21). This marks a large departure from Marxist ideology, as the foundation of this ideology calls for moving away from the capitalist tendencies of the bourgeoisie (Marx, 1848). Later, in many countries of Central and Eastern Europe, there were other attempts to implement market-oriented reforms, such as in Czechoslovakia in 1967 (Mason, 1996, p. 24). Moves toward market-oriented reforms increased, as communist leaders needed socioeconomic success in order to maintain legitimacy for their government and therefore remain in power (Mason, 1996).

The use of nationalism is another important deviation from Marxist ideology. Tito may have been the first to use nationalism as a source of legitimacy with his separate road to socialism (Mason, 1996). The “separate road” appealed to nationalism because it was a Yugoslavian road. Tito’s deviations differed from those of Soviet leaders because the Soviet leadership needed to build their legitimacy after the Revolution – whether by the New Economic Plan, or the use of terror to maintain control. As examined above, Tito did not need to create this legitimacy. While the leaders of the Soviet Union needed to deviate from Marxism to ensure control and maintain power over the people, Tito deviated from Marxism in order to keep his power independent from the Soviet Union. Furthermore, other leaders of socialist countries appealed to “socialist patriotism” in order to “win some popular support by stressing national interests and national autonomy” (Mason, 1996, p. 24). Thus, the ruling class of the socialist countries outside of the Soviet Union used nationalism in order to remain in power.

Inherent contradictions in Marxism resulted in the creation of what appears to be the most important deviation from the spirit of Marxism – instead of a classless society, a ruling class governed the USSR and the countries of East-Central Europe. To clarify, Marx (1848, p. 15) allowed for the proletariat to organize itself as a class, saying, “if, by means of a revolution, it makes itself the ruling class, and, as such, sweeps away by force the old conditions of production, then it will, along with these conditions, have swept away the conditions for the existence of class antagonisms and of classes generally, and will thereby have abolished its own supremacy as a class.” However, in contrast to Marxist calls for a classless society, the communist party, through heavy centralization, remained the ruling power long after the revolution. Mason (1996, p. 34) argues that many believed the Communist party was merely a “new class” that replaced the dominant bourgeoisie of the pre-transition systems. Thus, instead of fulfilling Marxist calls for a classless society, the communist party in the Soviet Union, and by extension the communist parties of Central and Eastern Europe, created yet another class-based system.

Finally, it is also extremely important to determine the causes of deviations from Marxism. As examined above, Marx provided for the creation of a proletariat ruling class; however, he did not foresee the perpetuation of this class. Therefore, the inherent contradiction or flaw of Marxist ideology lies in the fact that Marx calls for the creation of a dominant class in order to create a classless society. In order for a classless society to emerge, the ruling class must give up their dominant position in society. However, Marxism ignores the basic fallibility of human beings, for it is rare for an individual, or a group of individuals, to willingly give up power. Furthermore, other deviations from Marxist ideology, such as mixed-market economies and appeals to nationalism, resulted from a desire to maintain power. For example, the leaders of communist countries sought to legitimize their power by using both Marxist ideology and socioeconomic accomplishment (Mason, 1996). Because of the leadership’s lack of willingness to compromise, Marxist ideology stagnated under repression (Schöpflin, 1993). Thus, in the face of losing ideology as a source of legitimacy, socioeconomic progress gained in importance, and led the way to more market-oriented reforms (Mason, 1996). While the countries of Central and Eastern Europe followed Marxist ideology in many important ways, deviations emerged due to the inherent contradiction of Marxism – the creation of a proletariat ruling class in order to create a classless society.

While the existence of the Soviet Union and socialist countries in Central and Eastern Europe negates the argument that Marxism “has never been tried”, it is clear that deviations from Marxism emerged from contradictions in the ideology itself. By calling for the formation of a ruling class to create a classless society, this flaw in Marxism enabled communist leaders to use any means necessary to remain in power. As Kovaly (1996, p. 71) points out, “[i]t is often said that power corrupts, but I think what corrupted people in our country was not power alone but the fear that accompanied it…to lose power in our Communist society meant not a step down the social ladder to a former position, but a fall far below it.” The fact that a “social ladder” existed at all illustrates the flaws in the Marxist systems examined above. A utopian society where such a fear does not accompany power is perhaps the only society that can implement Marxism in its truest form.

Works Cited

- Dziewanowski, M. (1996). A History of Soviet Russia and Its Aftermath (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Espar, D. (Senior Producer), & Jones, B. (Producer/Director). (1998). Red Flag, 1917 [Videorecording]. (Available from WGBH Educational Foundation, Burlington, VT).

- Kovaly, H. (1996). Under a Cruel Star: A Life in Prague 1941-1968. New York: Holmes & Meier Publishers.

- Lenin, V. (1902). What is to be Done? In Internet Modern History Sourcebook [online]. Available: http://csf.colorado.edu/mirrors/marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1901/what-itd/index.htm

- Marx, K. & Engels, F. (1848). Manifesto of the Communist Party [online]. Available: http://www.anu.edu.au/polsci/marx/classics/manifesto.html

- Mason, D. (1996). Revolution and Transition in East-Central Europe (2nd ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Schöpflin, G. (1993). Politics in Eastern Europe, 1945-1992. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Sample 3. The Collapse and Legacies of Communism

Since the fall of communism in Eastern Europe little more than a decade ago, scholars have put forth numerous theories concerning the contributing factors to the collapse of one of the world’s most powerful systems. It is clear, however, that no single factor was solely responsible for the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe. Rather, several interacting developments led to the fall of communism. These developments include various economic problems, the emergence of a civil society, Gorbachev’s policies, and the causes and results of mass protests that first emerged in Poland. In order to determine what contributed to the fall of communism and the challenges of post-communist systems, one must examine the numerous important developments leading up to the collapse and the legacies of communism in post-communist Eastern Europe. Upon careful examination, it is clear that, while several developments contributed to the fall of communism, the leaders of the new governments in Eastern Europe had to deal with problems arising from the legacies of communism in the national, political and economic transitions into post-communism.

Economic decay was an important development in terms of the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe. By the 1980’s, the economies of East-Central Europe faced enormous problems such as stagnation and increasing indebtedness (Mason, 1996). This was especially dangerous given the fact that the legitimacy of the communist governments became increasingly associated with economic growth, or at least economic stability (Mason, 1996). The source of the economic decay that contributed to the collapse of communism was the fact that these economies were “concerned not with matching supply and demand, but with administering inputs and outputs” (Schöpflin, 1993). Furthermore, Mason (1996) points out that, while centrally planned economies could create expeditious growth in heavy industry, they could not facilitate growth in the more sophisticated consumer goods, service and technology sectors. In addition, consumers in East-Central Europe expected high growth levels (Mason, 1993). When high growth levels did not occur, mass protests soon confronted the communist governments, as was witnessed in Poland and elsewhere. Thus, the flaws in the economies of East-Central Europe resulted in the erosion of an essential aspect of legitimacy for the communist leadership.

The creation and expansion of a civil society in Eastern Europe was another important development in terms of the fall of communism. According to the principles of civil society, people should try and live outside of the official structures created by the communist authorities (Mason, 1996). This would include printing and reading samizdat or participating in the black market (Mason, 1996). Havel (1985) provided perhaps the best explanation of civil society and dissent. According to Havel (1985), lies created the foundation of the communist systems within East-Central Europe. Furthermore, the people perpetuated the existence of these systems because they accepted and lived within the lies established by the communist parties (Havel, 1985). Havel (1985, p. 27) used the example of a greengrocer who hangs a sign up in the window of his shop that reads “Workers of the World, Unite!” Havel (1985) asserted that the greengrocer may not necessarily believe in this slogan, but he hung the sign up for fear of reprisal. Havel (1985) defined dissent, not as overt and much publicized acts that gain attention in the West, but as simple acts that go against the established communist system. To use Havel’s (1985) illustration, this act may be as simple as refusing to place a sign in a window. Other examples of dissent may include refusing to vote in elections or buying goods on the black market instead of in state-owned stores. However, these simple acts have a far deeper meaning – by refusing to comply with the system, the dissident refuses to live within the lie (Havel, 1985). In addition, each of the dissident’s seemingly trivial acts puts a crack in the system of lies and ultimately results in the communist system’s collapse (Havel, 1985). Havel explained that “[i]n this revolt the greengrocer steps out of living within the lie. He rejects the ritual and breaks the rule of the game….He gives his freedom a concrete significance. His revolt is an attempt to live within the truth” (1985, p. 39). Thus, by simply refusing to live within the confines of the system established by the communist parties and becoming part of the civil society, dissent in East-Central Europe grew. This dissent, along with the removal of the threat of Soviet intervention, ultimately led to the fall of communism in Eastern Europe.

In addition to economic decay and the creation of a civil society, Gorbachev’s policies within the Soviet Union and toward Eastern Europe contributed significantly to the fall of communism in Eastern Europe. The first of these reforms came under the heading glasnost or “openness.” This included relaxed censorship on the press and allowed for the transmission of the Russian-language broadcasts of Voice of America and the BBC (Mason, 1996, p. 44). Gorbachev’s policy of glasnost was extremely important to the rest of his policies, especially concerning the economy and relations with both the West and Eastern Europe. According to one observer, “[w]ithout glasnost, the entire range of Gorbachev’s reforms would not have been possible” (Smith, 1990, p. 98). Therefore, by encouraging glasnost, especially in Eastern Europe, Gorbachev opened a floodgate and released calls for reform. Another part of Gorbachev’s policies was perestroika or “restructuring.” This aspect of Gorbachev’s policies within the Soviet Union dealt mostly with the economy, reducing the scope of the central ministries and “restricting them to long term and strategic planning” (Mason, 1996, p. 43). Furthermore, industries and agriculture were to be phased into a system of accountability and partial freedom that allowed them to establish their own prices and production schedules (Mason, 1996). Although Gorbachev introduced glasnost and perestroika within the USSR, his reforms provided a model for the countries of Eastern Europe because the USSR was the hegemonic power in the region. Any reforms in the USSR brought about calls for similar reforms in Eastern Europe. Thus, glasnost and perestroika in the USSR contributed to the fall of communism in Eastern Europe.

Along with glasnost and perestroika, Gorbachev also initiated democratizatcia, or democratization. For Gorbachev, both glasnost and democratization were necessary in order for successful economic reforms to occur. Included in democratization was the creation of the Congress of People’s Deputies, which was elected by Soviet citizens (Mason, 1996). Soviet citizens used this opportunity to remove several communist party officials (Mason, 1996). Perhaps the most important aspect of democratization is that Gorbachev allowed the emergence of groups independent from the Communist Party (Mason, 1996). This is extremely important in terms of the eventual collapse of communism in Eastern Europe. According to Mason, the “’national fronts,’ which first appeared in the Baltic republics, were ostensibly established to promote perestroika, but they eventually spread to every republic and became platforms for campaigns for national autonomy and independence” (1996, p. 46). In combination with democratization, Gorbachev’s other policy of revoking the Brezhnev Doctrine created conditions in Eastern Europe that resulted in the collapse of communism. Mason writes, “…more and more groups and individuals became active participants in the society, the economy, and the political system. Almost imperceptibly, the Soviet system evolved to a point at which the clock could not be turned back” (1996, p. 46).

It is possible to see each of the developments examined above at work in the fall of communism in Poland. Economic problems, a civil society, and Gorbachev’s reforms all contributed to the outbreaks of mass protests. In turn, these protests paved the way for discussions, roundtable negotiations, and elections that ultimately toppled the communist leadership (Mason, 1996). For example, economic problems in Poland in the late 1980’s were widespread. Poland had a huge hard currency debt that reached upwards of $40 billion (Mason, 1996). This debt, in combination with the realization that Gorbachev was not likely to intervene on behalf of the conservative leaders in Warsaw, led Polish workers into two rounds of massive strikes in 1988 (Mason, 1996). In spring of 1988, the workers’ demands came to include calls for political changes, such as the legalization of Solidarity (Mason, 1996). While Solidarity was illegal under the laws of the communist government, it remained an important element in Poland’s civil society. In August of 1988, the Interior Minister met with Solidarity leader Lech Walesa in order to discuss the legalization of Solidarity if Walesa could convince the workers to end the strike (Mason, 1996). The participants in later roundtable negotiations established rules for new parliamentary elections that allowed Solidarity to compete for 35 percent of the seats in the Sejm and all of the 100 seats in the Senate (Mason, 1996). The results of the roundtable negotiations were extremely important in terms of the fall of communism in Poland and the rest of Eastern Europe. Finally, in June of 1989, the Polish leadership held elections, with Solidarity winning all of the contested seats in the Sejm and 99 of the 100 seats in the Senate (Mason, 1996). These events marked the first time in the history of communism that a noncommunist government took power (Mason, 1996). Thus, the combination of developments, including economic decay and the creation of a civil society, ultimately resulted in the downfall of the communism in Poland. Furthermore, Gorbachev’s lack of hostility, and perhaps approval, of the new non-communist government provided a signal to the people in other Eastern European countries that “the Brezhnev Doctrine was dead” (Mason, 1996, p. 54). This paved the way for more non-communist governments to emerge in Eastern Europe. It is important to note that the events that led to the downfall of communism in Poland signified more than the consequences of economic decay, the creation of a civil society and Gorbachev’s policies. Rather, the events in Poland acted as a catalyst to the further collapse of communism in Eastern Europe. Gorbachev’s glasnost permitted other Eastern Europeans to learn about, and in many ways try to replicate, the astonishing events that transpired in Poland.

After communism collapsed in a cascade of protests and relatively peaceful change, the Eastern European countries had to face similar dilemmas in their post-communist national, political and economic spheres. Offe (1991, p. 865) refers to the process of development from a communist to a post-communist country as the “triple transition.” In addition, Offe (1991) contends that there is a hierarchical arrangement within the triple transition, with national issues taking precedence over political and economic issues. However, it is important to note that developments in each of these three spheres can influenced developments in the others. For example, national questions have ramifications on political questions, and vice versa.

In terms of Offe’s (1991) hierarchy, it is important to address the development of the national spheres in post-communist Eastern Europe with relation to the legacies of communism. Under communism, national questions became subordinate to class unity. Mason points out that “federal and multinational states had been held together for generations by a dominating communist party” (1996, p. 113). Thus, communist leaders in Eastern Europe, following the Soviet model, did not permit nationalism in order to maintain the communist party’s monopoly of power. However, Mason goes on to point out that “[a]s the countries became more open and central controls were lifted, nationalism began to tear them apart” (1996, p. 113). Thus, post-communist countries had to first, according to Offe (1991, p. 869), “decide who ‘we’ are.” However, this decision was difficult at best, and in some ways contradictory to democratic principles (Offe, 1991). The difficulty was in the fact that the population had to decide democratically who the demos, or people, are. However, in order to do that, the population had to decide first who could participate in the election. Therefore, post-communist systems faced a difficult situation. Various post-communist countries, such as Poland and Hungary, had easier times solving this problem because their populations were relatively homogeneous. Czechoslovakia was unique in terms of problems in the national sphere between the Czechs and Slovaks in that country. Unlike other ethnically heterogeneous countries in Eastern Europe, in Czechoslovakia the Czechs and the Slovaks primarily lived in two different regions of the country that had relatively clear boundaries. Therefore, when the tensions between the Czechs and the Slovaks increased, the decision to separate the two regions, as well as the separation itself, were not difficult or violent (Mason, 1996). Thus, the Czech Republic and Slovakia dealt with their national problems in a peaceful way. However, in countries such as Russia and Yugoslavia, with several nations and unclear borders between these nations, many national groups used violence instead of democracy to settle their national problems.

Communism also left important legacies concerning the challenges in the political spheres of post-communist Eastern European countries. In communist systems, the communist party of each Eastern European country held a monopoly of power. Furthermore, the Eastern European countries generally adopted the Soviet model of parallel political and party structures (Mason, 1996). While the public theoretically elected members of the political structures, because of the communist party’s monopoly of power, voters effectively only had one option (Mason, 1996). After the fall of communism, each of the Eastern European countries had to deal with similar challenges. There was little doubt that each of the post-communist countries would be democratic and have multiple parties. The forms of the revolutions in the post-communist countries assured that there would at least be a communist-successor party and one opposition group. However, each of the post-communist systems had to create new constitutions, as well as to decide on the types of political institutions to establish (Mason, 1996). For example, the post-communist leadership had to decide if they would have a President, a Prime Minister, or both. In addition, the new post-communist leadership had to establish the procedures to elect members of the legislative and executive branches.

The legacies of communism also affected the economic sphere in the post-communist systems in Eastern Europe. Communism favored a command economy, in which the state owned all industries and the ministries overseeing each industry, under the leadership of GOSPLAN, made all economic decisions. Therefore, when the time came for the transition between the command economies of communism to the market economies of post-communism, Eastern European countries had to deal with numerous dilemmas. Mason points out that “[t]he major tasks of domestic economic restructuring included price deregulation, monetary and fiscal reforms, the elimination of government subsidies to both consumers and producers, creation of a modern banking system, and a large-scale program of privatization of state enterprises and farmland” (1996, p. 123). For example, in the transition from a command to a market economy, the market must determine prices (Mason, 1996). Therefore, in the early stages of the economic transition in Eastern Europe, most countries faced rapid inflation. In addition, post-communist regimes in Eastern Europe had to deal with the communist legacy of state ownership of industries (Mason, 1996). Some countries, such as the Czech Republic, created a stock market and sold stock in various companies using a program of voucher privatization. Others, such as Hungary, sold industries, or parts of industries, directly to foreign investors or to other private groups.

In addition, while communism left legacies and difficulties in the individual national, political and economic spheres, it also resulted in the fact that each sphere interacted with, and had repercussions on, the other spheres in the triple transition. Because communist systems controlled every aspect of society, when these systems collapsed, the countries of Eastern Europe had to deal with transitions in their national, political and economic spheres simultaneously (Mason, 1996). Therefore, it is not surprising that the spheres of the triple transition in Eastern European countries influenced each other. For instance, adding to the difficulty of creating functioning democratic systems in the countries of Eastern Europe was the interaction with the national sphere in the new post-communist systems. According to Linz and Stepan, “[t]wo of the most widely cited obstacles to democratic consolidation are the dangers posed by ethnic conflict in multinational states and by disappointed popular hopes for economic improvement in states undergoing simultaneous political and economic reform” (1996, p. 23). As examined above, countries such as Poland and Hungary were relatively successful in creating consolidated democracies because their national problems were minor or nonexistent. However, Yugoslavia faced almost insurmountable difficulties and consequently broke apart.

Furthermore, the economic sphere affected the political sphere in post-communist countries. The public’s response to the hardships of changing from a command to a market economy is the most obvious illustration of the impact of economics on politics. In Poland for example, which underwent “shock therapy” that created many hardships in the first few years of the transition, the Polish people elected a communist-successor party (Mason, 1996). It is important to note, however, that this election, as well as elections with similar outcomes in many Eastern European countries, illustrated the stability of their democratic systems (Mason, 1996). Mason points out that “the return to power of former communist parties…marked an important point in the evolution of democratic politics: the peaceful and routine accession to government of the former ‘opposition’ parties” (1996, p. 114).

The influence of the political sphere on the economic sphere in Eastern Europe provides another example of the interaction between each aspect of the triple transition. Offe (1991) points out that democratization in the political sphere can contradict with marketization in the economic sphere. Furthermore, Offe (1991) contends that, in most cases, political leaders introduce and create a market economy under predemocratic conditions. However, because the transitions to a market economy and democratization were simultaneous in post-communist countries, “the introduction of a market economy…has prospects of success only if it rests on strong democratic legitimization” (Offe, 1991, p. 881). Therefore, developments in the political sphere of post-communist systems were extremely important to the establishment of market economies in Eastern Europe.

Numerous factors, such as economic decay, the concept of civil society, and Gorbachev’s reforms, contributed to the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe. However, despite differences in geography and ethnicity, each of the countries in Eastern Europe faced similar transitions into the post-communist world. Offe’s triple transition provides the best elucidation of this progression into post-communism. The legacies of communist rule affected the development in the national, political and economic spheres in the countries of Eastern Europe. While some countries in Eastern Europe may have been more successful in dealing with national, political and economic problems than others, it is clear that each of the post-communist countries still have more hurdles to overcome. For some, such as Hungary, this may involve admission into the European Union (Kosztolanyi, 1999). For others, this progress may be less concrete. In Havel’s words, “[w]e need, quite simply, a new vision: one that is mindful of the future role of our citizens…one that considers the cultivation of our citizens’ lives, our political and economic identity, and our country’s position within the European context” (1996, p. 12).

Works Cited

- Havel, V. (1985). The Power of the Powerless. (J. Keane, Ed.). Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

- Havel, V., Klaus, V., & Pithart P. (1996). Rival visions. Journal of Democracy, 7(1), 12-23.

- Kosztolanyi, G. (1999, December 13). Csardas: Hungarian hopes – The events of 199 in review. Central Europe Review – Hungary: 1999 Reviewed, 1(25).

- Linz, J. & Stepan, A. (1996). Toward consolidated democracies. Journal of Democracy, 7(2), 14-33.

- Mason, D. (1996). Revolution and Transition in East-Central Europe (2nd ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Offe, C. (1991, Winter). Capitalism by democratic design? Democratic theory facing the triple transition in East Central Europe. Social Research, 58, 865-892.

- Schöpflin, G. (1993). Politics in Eastern Europe, 1945-1992. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- Smith, H. (1990). The New Russians. New York: Random House.

Sample 4. Response to the following question:

I. There are many possible ways of deciding how to spend the money we have collected for nonprofits. What is electoral system do you prefer for translating the preferences of the class into an allocation of money? What advantage does this system have over alternative systems? What disadvantages does this system have over alternative systems?

II. We will also have a class parliament. What is electoral system do you prefer for translating the preferences of the class into an allocation of parliamentary seats to individuals? What advantage does this system have over alternative systems? What disadvantages does this system have over alternative systems?

III. Bonus: The answers to the questions above constitute your ballot for the election of the choice of electoral system. This, too, requires an electoral system. Yet the in light of the information I will receive on your “ballots” and other considerations that may occur to you, the choices of electoral system for choosing the electoral system are limited. What are the limitations? What electoral system(s) can we use to choose the electoral system?

In the course of its worldwide expansion, democracy has affected territories and states of tremendous diversity. Given the variance of these regions, there is little surprise that their electoral systems vary significantly. As the key feature of democracy, electoral systems must provide the most effective mechanism for a given population to express its preferences, and this must occur in the context of its own distinct political circumstances. In a similar vein, a unique population of voters will also hold the class elections. To best develop an electoral system for the class, a designated set of evaluation criteria is needed, and these criteria must be applied relative to the class’s goals and political circumstances. With this in mind, the list system of proportional representation and the single transferable vote are best suited for the class allocation of money and the parliamentary elections, respectively. Both systems satisfactorily meet critical evaluation criteria, hold up admirably to criticisms leveled against them, and best suit the unique environment in which the class elections will be held.

What, then, constitutes an effective electoral system? Andrew Reynolds and Ben Reilly (2003) identify several criteria for evaluation, including representation, accessibility, accountability, and government efficiency. A key factor they use to judge a system’s representative ability is whether the elections “adequately reflect the ideological divisions within society” (Reynolds and Reilly, 2003). The authors associate accessibility with “ease of voting” and the ability of the electorate to understand the mechanics of the process by which their votes are counted (Reynolds and Reilly, 2003). They define accountability as a state in which elected officials or parties are “responsible to their constituents to the highest degree possible” (Reynolds and Reilly, 2003). In other words, parties and officials must be able to lose elections as punishment for not delivering results. Reynolds and Reilly (2003) associate the efficiency of the government with its stability. This criterion involves voter perception of fairness in the electoral system, and it also examines the ability of the government to efficiently implement policy (Reynolds and Reilly, 2003).

The authors make one other vital point in their work. They note that these criteria are often incompatible with one another, and therefore a tradeoff must be made when designing an electoral system that best suits the needs and objectives of the target population (Reynolds and Reilly, 2003). With that in mind, these criteria can be employed to determine which electoral systems are most effective for the class elections.

The ideal system for determining how to spend the money collected for non-profit organizations in class is the list system of proportional representation (referred to hereafter as “List PR”.) The mechanics of this electoral system’s construction can vary considerably. Since list PR is essentially a party-based system, the class should maintain its current political parties, and voters can then cast their ballots for the parties which, in turn, represent the charities that receive the donations. The class should operate as one district, with a designated district magnitude of perhaps five. This would avoid the confusion of having many small districts, each composed of as few as five people, as well as the problems caused by absenteeism in such small districts. Each “seat” in the election represents an equal amount of money being distributed to the parties in that election. The parties themselves are then responsible for choosing what charities will receive money and in what proportion the money will be divided within the party. In the sense that the parties decide what charities will receive their share of the money if elected, a closed list system exists because the voters have no say over this matter when they vote. The final detail of the system to be decided is the method by which the votes are counted. The class should use the highest average system for counting the votes, not because it would have a significant impact on the results in a class as small as ours, but simply because it is the most popular counting method for List PR systems (Ferrell, 1998, 64).

Having laid out the basic mechanics of the system, list PR reveals tremendous advantages as the electoral system for allocating money. It most directly satisfies Reynolds and Reilly’s (2003) representation criterion because it corresponds seats with voter’s preferences while creating fewer wasted votes than say, a plurality system. Given the relatively low population of the class, there is little need to limit proportionality by imposing a threshold to prevent “extreme” parties from forming. It is much more likely, in fact, that an “effective” threshold will be imposed by the system itself due to the number of parties able to win the election itself (Reynolds and Reilly, 2003). An unpopular or minority party has a significantly greater chance at winning a portion of the money under this system as voters are more confident to vote for such parties. This perception of fairness satisfies Reynolds and Reilly’s (2003) stability criterion.

In spite of its strengths, several criticisms can be launched against this electoral system. The first accuses List PR of giving extremist parties a platform and therefore running the risk of destabilizing the system itself. Given the size of the class, this can be countered by using the d’Hondt divisors when counting the votes. The d’Hondt divisors provide the least proportional result under the highest average system and would therefore limit the possibility that extremist parties can win money in or otherwise exercise negative influence on the election (Ferrell, 1998, 65). Another weakness of this electoral system is inability to remove parties from power, and therefore not meeting Reynolds and Reilly’s (2003) accountability criterion. Theoretically speaking, if a particular party became undesirable to the electorate in some way, the voters still have the ability to hold that party accountable for its actions. Even if the offending party is not completely ousted from power, voters can still significantly curtail its influence. One final disadvantage leveled against list PR is the weak link between representatives and their constituency (Reynolds and Reilly, 2003). Ferrell (1998, 68) notes that this problem is magnified by the existence of only one electoral district, which is what was proposed for the class. Yet here again, the relatively small class size neutralizes this concern quite obviously.

The List PR system, then, is best for deciding how to spend the charitable money. A separate system is ideal for electing a class parliament. This ideal system is the Single Transferable Vote (referred to hereafter as “STV”.) This system is considerably less party-oriented and therefore should focus more on candidates for the purpose of our class’s parliamentary elections. Once again, given the class size and the complexity of districting, the entire class should be one district under the STV system. A designated number of seats must be chosen for parliament, setting the district magnitude anywhere between five and ten seats. The ballot structure should feature the names of the candidates, preferably in random order, and disclosure of their party affiliation should be optional. Like all STV systems, the Droop quota would be employed to count the votes.

The operation of an STV system reveals its inherent advantages. As a proportional electoral system, it shares the advantages of list PR. In this regard, it satisfies Reynolds and Reilly’s (2003) representation and stability criteria as described above. STV has an added advantage over List PR, however, in the area of accountability. Since voters identify candidates instead of parties on the ballots, members of parliament are presumably more likely to respond to the demands of the electorate. Reynolds and Reilly (2003) note that STV gives a significant advantage to independent candidates (or in the class’s case, to candidates who choose not to disclose their parties) because voters have the opportunity to choose between candidates themselves instead of parties.

The STV system nevertheless has several noteworthy criticisms. The first disadvantage is the perceived lack of accessibility, generally supported by the uniqueness of preferential voting (Reynolds and Reilly, 2003). There is little doubt that STV is more complex than say, the First Past the Post system. Yet once again, considering the size limit of the class and the presumed educational level of its members, this hardly seems to be a significant weakness in using it to elect a class parliament. A long ballot and consequential voter fatigue would likely be more realistic problems, and in that regard, voters should simply not be required to rank all the candidates on the ballot. A final weakness of STV identified by Reynolds and Reilly (2003) points to the intra-party conflict and fragmentation due to the competition of candidates from the same party. This problem is confronted by allowing candidates to run as independents or giving them the option not to declare their party affiliation. Reynolds and Reilly (2003) go on to note that this potential weakness, along with the others, has actually turned out to be quite insignificant in states practicing the STV system.

Using criteria laid out by Reynolds and Reilly (2003) and adapting those criteria to the unique political environment of the class, two electoral systems were identified as ideal to the class elections. The list system of proportional representation was deemed ideal for the distribution of charitable money and the single transferable vote system was deemed most appropriate for the class’s parliamentary elections. These systems will provide the class with representative results, produce a stable system, and be quite accountable to the voters in each election. Each of the chosen systems responds admirably to criticism largely by adapting itself to the uniqueness of the class size and the methodology of each prospective election. In addition, these systems spare the class from wasted votes inherent in systems that incorporate majoritarian or plurality methods. The class is also spared from districting, which is required under non-proportional systems. The class, like states around the world, contains a voting population that has a unique set of needs and circumstances, and therefore an electoral system must be designed for it that best translates those needs into an acceptable electoral outcome.

Literature Cited

- Farrell, David M. 1998. Comparing Electoral Systems London: Macmillan.

- Reynolds, Andrew, and Ben Reilly. 2003. Administration and Cost of Elections Project.

Available WWW: http://www.aceproject.org/main/english/index.htm [Accessed 21 February 2005].

Bonus response

The electoral system for determining the electoral systems used in class is limited. To begin with, it is quite obvious that there should be two elections for determining the electoral system: one for how the class spends the charitable money and the other for the election of parliament. This of course requires each student’s “ballot” to be counted twice.

There is however another limitation that is less obvious. Only one electoral system will presumably be used for each election. This effectively means there is a “district magnitude” of one, because only one winner can prevail in the election. This rules out all electoral systems incorporating proportional representation, including STV, mixed member proportional, and all forms of List PR, since all of these systems must, by definition, have a district magnitude of greater than one. Although the Alternative Vote is a non-proportional system, it cannot be used either, because students did not rate their electoral preferences as this system requires. The electoral system for determining the electoral systems for the class is therefore restricted to non-proportional systems such as the First Past The Post and the Second Ballot methods.

Another potential problem is revealed by noting the various possibilities and combinations of the student’s electoral preferences for, making it quite difficult to conduct a systematic count. For example, it might prove necessary to combine all the ballots that advocate List PR for parliamentary elections, in spite of the fact that students will most likely advocate different forms of List PR such as the highest average system or the largest remainder system, among other variations. If List PR won the election in this way, then a second vote would be necessary to determine which form of List PR was most preferred among the ballots favoring List PR.

Excellent post today by Sean Hanley on the potential of the “new”(ish) Czech Party “Sovereignty” which perfectly corresponds to all that is interesting to me about the region’s politics these day:

Excellent post today by Sean Hanley on the potential of the “new”(ish) Czech Party “Sovereignty” which perfectly corresponds to all that is interesting to me about the region’s politics these day:

I love Slovakia. I also love the Czech Republic.

I love Slovakia. I also love the Czech Republic.  And if you do to–or if you want to–now’s your chance: Fulbright Scholarships to both of these countries are available and–with the right plan of action–not out of reach for any US citizen with academic interests. I went as a researcher but they are also–especially–looking for those who would go there as teachers, and most academic specializations would have something to contribute. I am exceedingly grateful to have had this chance and I /strongly/ recommend others to take a chance. Even the process of application is useful for helping plan for the future. Fulbright has a nice flyer on this–see below or click

And if you do to–or if you want to–now’s your chance: Fulbright Scholarships to both of these countries are available and–with the right plan of action–not out of reach for any US citizen with academic interests. I went as a researcher but they are also–especially–looking for those who would go there as teachers, and most academic specializations would have something to contribute. I am exceedingly grateful to have had this chance and I /strongly/ recommend others to take a chance. Even the process of application is useful for helping plan for the future. Fulbright has a nice flyer on this–see below or click