I love Slovakia. I also love the Czech Republic.

I love Slovakia. I also love the Czech Republic.  And if you do to–or if you want to–now’s your chance: Fulbright Scholarships to both of these countries are available and–with the right plan of action–not out of reach for any US citizen with academic interests. I went as a researcher but they are also–especially–looking for those who would go there as teachers, and most academic specializations would have something to contribute. I am exceedingly grateful to have had this chance and I /strongly/ recommend others to take a chance. Even the process of application is useful for helping plan for the future. Fulbright has a nice flyer on this–see below or click here for a pdf–that you can use or pass on to others among colleagues and friends, and you can find out more here: www.iie.org/cies

And if you do to–or if you want to–now’s your chance: Fulbright Scholarships to both of these countries are available and–with the right plan of action–not out of reach for any US citizen with academic interests. I went as a researcher but they are also–especially–looking for those who would go there as teachers, and most academic specializations would have something to contribute. I am exceedingly grateful to have had this chance and I /strongly/ recommend others to take a chance. Even the process of application is useful for helping plan for the future. Fulbright has a nice flyer on this–see below or click here for a pdf–that you can use or pass on to others among colleagues and friends, and you can find out more here: www.iie.org/cies

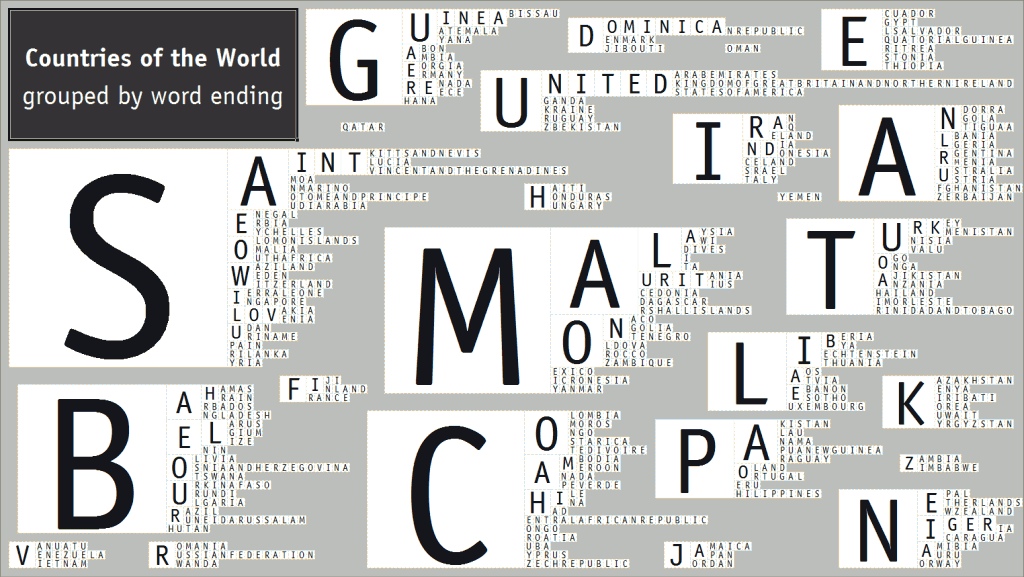

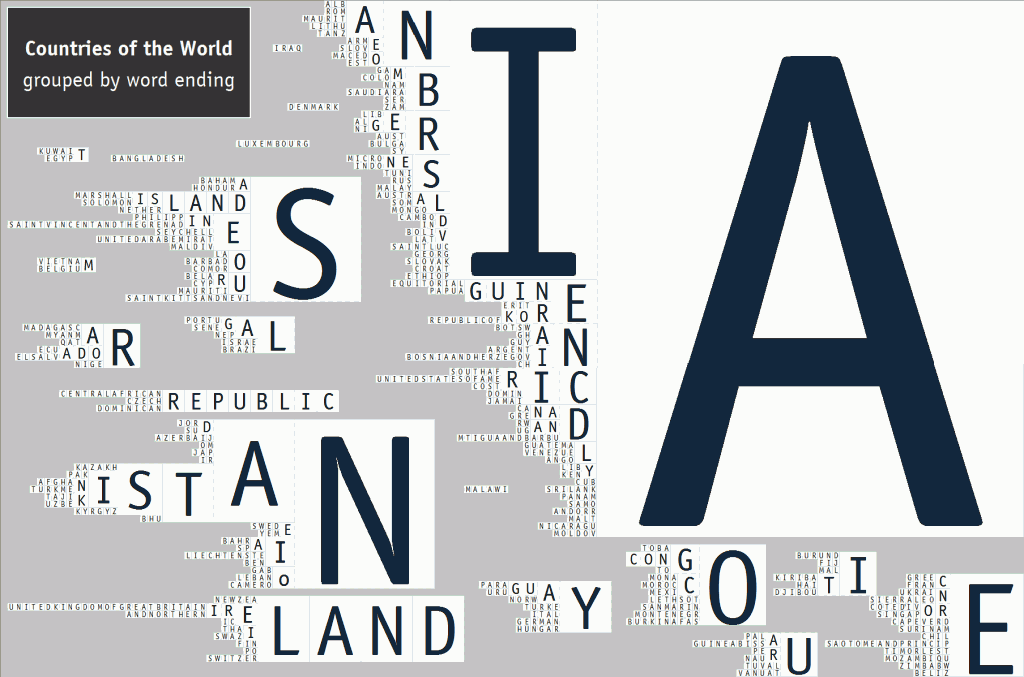

Make your own country name, part II. This time with real countries

This is the way the world ends, not with a b-a-n-g but with an -n-i-a.

At least that’s the way a good share of the world’s country names end. Having used fictional country data to make “maps” of the beginnings and endings of non-existent countries, it was an obvious next step to try it with the real world. So as with Ballnavia and Slaka and Molvania, I inverted the names on the United Nations member list (English-language version) and alphabetized by last letter and then arrayed them graphically with size representing frequency (actually it represents frequency squared, but I think that actually helps draw out the patterns). What I got was actually not much different from the results for make-believe Europe:

I did the same with a normal forward-facing alphabetization. and again got a similar result, again suggesting that country beginnings are the source of much more variety than country endings.

So from here it’s a simple step to yet another matrix of beginnings and endings, again ranked by my formula of “length of character string” times “frequency of appearance.” Draw lines from prefix to suffix to make your own country names. Add letters in between to increase the excitement:

| Pts. | # | Prefix | <————-> | Suffix | # | Pts. |

| 20 | 10 | MA | IA | 37 | 74 | |

| 18 | 3 | UNITED | LAND | 9 | 36 | |

| 16 | 2 | DOMINICA | STAN | 7 | 28 | |

| 15 | 3 | SAINT | NIA | 9 | 27 | |

| 15 | 5 | MAL | ISTAN | 5 | 25 | |

| 12 | 2 | GUINEA | REPUBLIC | 3 | 24 | |

| 10 | 2 | NIGER | TAN | 8 | 24 | |

| 10 | 5 | CO | ANIA | 5 | 20 | |

| 10 | 5 | MO | GUINEA | 3 | 18 | |

| 10 | 5 | PA | KISTAN | 3 | 18 | |

| 9 | 3 | BEL | ELAND | 3 | 18 | |

| 9 | 3 | MON | LANDS | 3 | 15 | |

| 8 | 2 | MALA | ICA | 5 | 15 | |

| 8 | 2 | SLOV | RICA | 3 | 12 | |

| 8 | 2 | TURK | MBIA | 3 | 12 | |

| 8 | 4 | CA | ERIA | 3 | 12 | |

| 6 | 2 | BAH | SIA | 4 | 12 | |

| 6 | 2 | CHI | KOREA | 2 | 10 | |

| 6 | 2 | GRE | NESIA | 2 | 10 | |

| 6 | 2 | IRA | ILAND | 2 | 10 | |

| 6 | 2 | IND | CONGO | 2 | 10 | |

| 6 | 2 | LIB | ES | 5 | 10 | |

| 6 | 3 | AN | ANA | 3 | 9 | |

| 6 | 3 | BO | INA | 3 | 9 | |

| 6 | 3 | BU | NADA | 2 | 8 | |

| 6 | 3 | NE | ANDA | 2 | 8 | |

| 6 | 3 | SE | ALIA | 2 | 8 | |

| 6 | 3 | SO | ENIA | 2 | 8 | |

| 6 | 3 | SW | ONIA | 2 | 8 | |

| 4 | 2 | AL | GUAY | 2 | 8 | |

| 4 | 2 | AR | DIA | 2 | 6 | |

| 4 | 2 | AU | VIA | 2 | 6 | |

| 4 | 2 | BR | DAN | 2 | 6 | |

| 4 | 2 | FI | AIN | 2 | 6 | |

| 4 | 2 | GA | DOR | 2 | 6 | |

| 4 | 2 | GE | LA | 3 | 6 | |

| 4 | 2 | JA | TI | 3 | 6 | |

| 4 | 2 | LA | AL | 3 | 6 | |

| 4 | 2 | LE | CO | 3 | 6 | |

| 4 | 2 | NA | AR | 3 | 6 | |

| 4 | 2 | PO | OS | 3 | 6 | |

| 4 | 2 | SI | US | 3 | 6 | |

| 4 | 2 | SU | YA | 2 | 4 | |

| 4 | 2 | TO | CE | 2 | 4 | |

| 4 | 2 | TA | EN | 2 | 4 | |

| AS | 2 | 4 | ||||

| AU | 2 | 4 |

And what can we take from this? Well, if you’re a serious, reality-minded person, not much. But if you like to make stuff up and tell stories and have fun with words, then you get some great new opportunities to create things that sound like countries but really aren’t. Below, in alphabetical order, because I can’t pick a favorite, is a partial list of some of the possibilities. Some are just variations on existing country names with the right amount of detail in the prefix: Malistan and Malaguay sound about right, with the right number of syllables and are enriched by the common prefix “Mal”–with its ominous undertones in Latin and its implication of smallness in Slavic languages). Mondor, too, sounds sinister, though not quite as bad as its its Middle-Earth counterparts.

Among the others, I like the triple combination of Tailand, Toeland and Toiland (somewhere between Santa’s workshop and the nearby WC). Two others–Monica and Nadia–highlight the similarity between country names and Indo-European names for females. Panada and Swina sound vaguely like animals. Many sound like serious medical conditions, especially Annesia, Mania, Maleria and Maladia. And there are some that end in the “ya” sound, and begin with verb-sounding prefixes. Tasia sounds like “Tase ya” (no place for Andrew Meyer) and the same possibilities apply to Suya (a response, perhaps, to Tasia), to Bombia, and, somewhat less belligerently, to Combia and Boeria. And one of the really nice things about the list is that contains at least two “real” fake countries: Sodor, far more real to most 4-year-old Thomas the Tank Engine fans than the country in which they actually live, and Catan, equally real to many players of German-style board games. So, to would-be game designers, authors of children’s stories, and all those others who want to see their name in lights, I say use the chart. Neonia is within reach.

- ANANA

- ANNESIA

- BOMBIA

- CATAN

- COMBIA

- COSIA

- FINESIA

- IRAMBIA

- MALADIA

- MALAGUAY

- MALERIA

- MALISTAN

- MANIA

- MONDOR

- MONICA

- NADIA

- NEONIA

- PANADA

- SAINT REPUBLIC

- SODOR

- SUYA

- SWINA

- TAILAND

- TASIA

- TOELAND

- TOILAND

- UNITEDLAND

P.S. It’s hard for me not to notice that Sodor Railways logo on the Wikipedia page, while obviously lovingly crafted by a fan with strong graphics skills also bears a striking and unfortunate resemblance to another not too different insignia with a black squiggly line inside white circle on a dark red field. As Marta von Trapp wisely observes in The Sound of Music, “Maybe the flag with the black spider makes people nervous!”

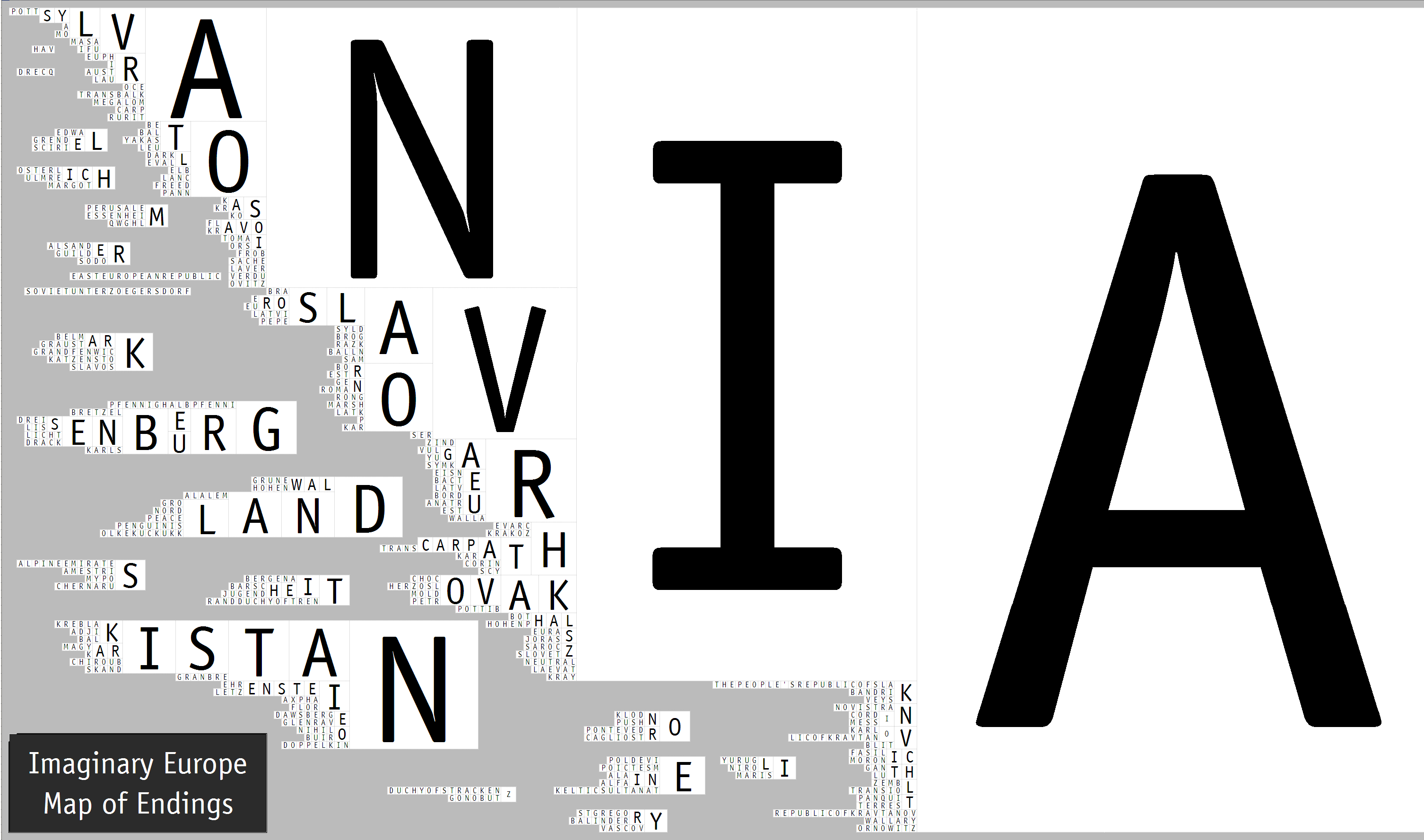

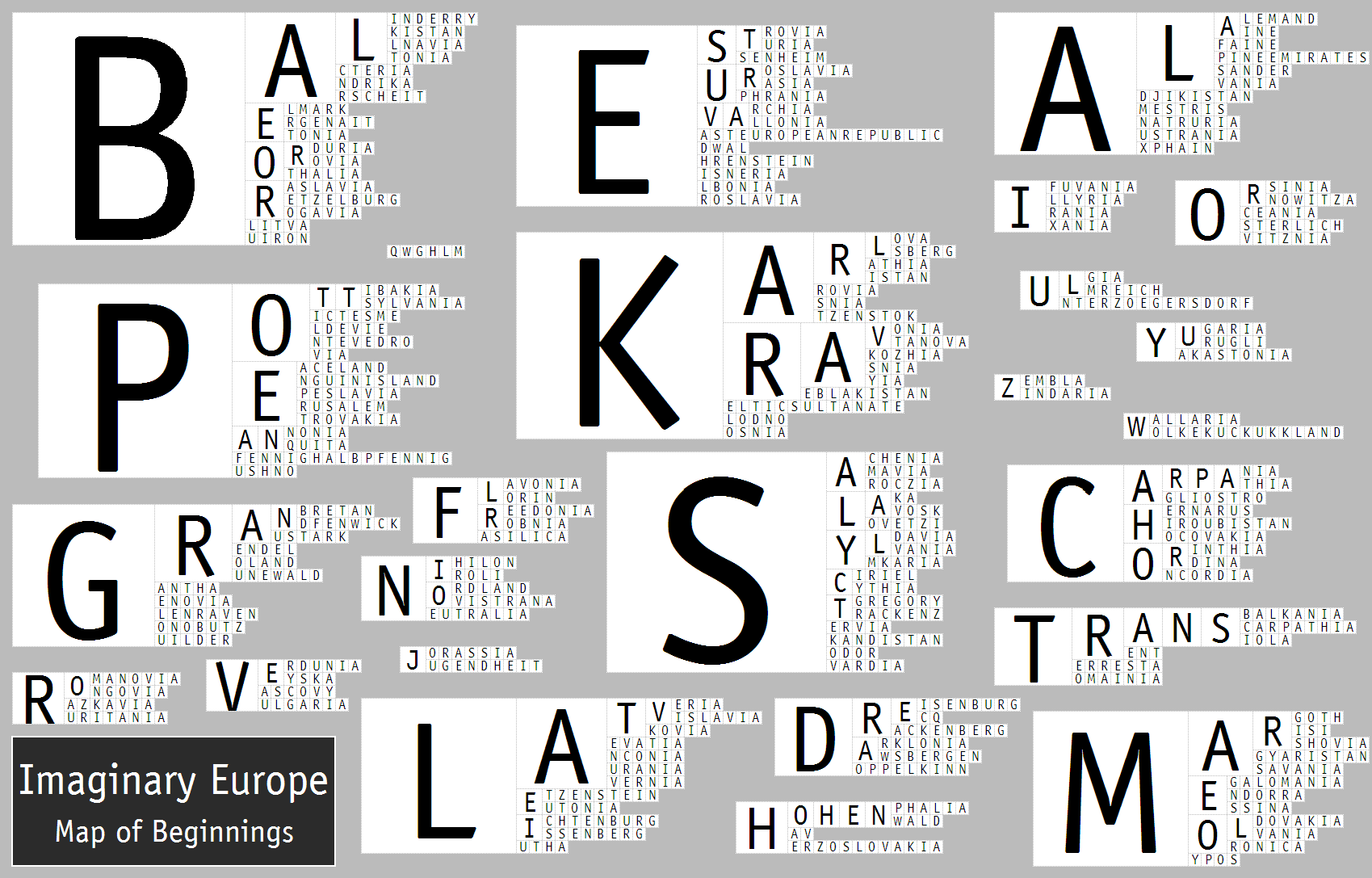

A map of non-existent European countries (and how to create your own)

Earlier this year I decided to leave Elbonia. Elbonia served me well during over a decade of exams about hypothetical Eastern European countries that allowed me to test whether my students could apply their abstract knowledge to new and unfamiliar cases. But after a decade of references to the Dilbert cartoons in which I first encountered it, Elbonia began to feel as stale as Dilbert itself. And since I did not want simply to switch to another cliche like “Vulgaria” or “Ruritania,” I did a search for a list of “fictional European countries” and immediately found a wikipedia page that I didn’t expect to exist: List of Fictional Countries and an even more specific List of Fictional European Countries.

Earlier this year I decided to leave Elbonia. Elbonia served me well during over a decade of exams about hypothetical Eastern European countries that allowed me to test whether my students could apply their abstract knowledge to new and unfamiliar cases. But after a decade of references to the Dilbert cartoons in which I first encountered it, Elbonia began to feel as stale as Dilbert itself. And since I did not want simply to switch to another cliche like “Vulgaria” or “Ruritania,” I did a search for a list of “fictional European countries” and immediately found a wikipedia page that I didn’t expect to exist: List of Fictional Countries and an even more specific List of Fictional European Countries.

And with this raw material, I could not help but take this one step further and to look for some underlying patterns that might even allow me to create new ones. It wasn’t much of a problem to look for common beginnings by alphabetizing the list. It was slightly more complicated to find common endings by alphabetizing from the last letter forward, but some playing with Excel took care of that. These lists were not as useful as I had hoped, however, because many countries many ended in A, many of those in -I-A and many of those in -V-I-A. How to find the patterns? The answer I came up with was to display these graphically, with letter sequences according to first and last letter and letter size according to frequency, sort of a wordcloud but accounting for the proximity of related characters. (There’s probably some name and algorithm for this. I usually end up reinventing the wheel).

Since the letter sequence took up less space when positioned next to one another than in a long list—and since the resulting arrangement had a topographical look, it was almost natural to actually turn the list into something maplike. And that is what I eventually did and what I present below: a map-like array of imaginary European country names according to beginnings and endings.

And the same array that produced this map can be also used for my initial goal: the creation of new names. For no reason other than that it seemed right, I weighed each ending by the multiple of its frequency and its length. This means that very simple beginnings and endings, like “A” have a high frequency score discounted by short length, while much longer (and more interesting) names, like “I-S-T-A-N” are discounted by their relative rarity. The result is the list below or in a pdf worksheet here: Imaginary Europe Matrix

| Pts. | # | Prefix | <————> | Suffix | # | Pts. | ||

| 15 | 5 | KAR | IA | 92 | 184 | |||

| 15 | 5 | KRA | NIA | 38 | 114 | |||

| 15 | 3 | TRANS | VIA | 20 | 60 | |||

| 12 | 4 | BAL | ONIA | 12 | 48 | |||

| 12 | 6 | PO | AVIA | 10 | 40 | |||

| 10 | 5 | PE | OVIA | 9 | 36 | |||

| 10 | 5 | MA | ISTAN | 7 | 35 | |||

| 10 | 2 | HOHEN | RIA | 11 | 33 | |||

| 10 | 2 | CARPA | VANIA | 6 | 30 | |||

| 9 | 3 | LAT | SLAVIA | 5 | 30 | |||

| 9 | 3 | MAR | LVANIA | 4 | 24 | |||

| 8 | 2 | POTT | OVAKIA | 4 | 24 | |||

| 8 | 2 | GRAN | ARIA | 5 | 20 | |||

| 8 | 2 | KARL | LAND | 5 | 20 | |||

| 8 | 2 | KRAV | RANIA | 4 | 20 | |||

| 6 | 3 | BE | TONIA | 4 | 20 | |||

| 6 | 2 | BOR | HIA | 6 | 18 | |||

| 6 | 3 | BR | CARPATHIA | 2 | 18 | |||

| 6 | 3 | ME | KISTAN | 3 | 18 | |||

| 6 | 2 | MOL | SYLVANIA | 2 | 16 | |||

| 6 | 3 | SA | ROSLAVIA | 2 | 16 | |||

| 6 | 2 | SLA | ROVIA | 3 | 15 | |||

| 6 | 2 | SYL | KIA | 5 | 15 | |||

| 6 | 2 | DRE | ARISTAN | 2 | 14 | |||

| 6 | 3 | CH | ERIA | 3 | 12 | |||

| 6 | 2 | COR | URIA | 3 | 12 | |||

| 6 | 2 | ALA | BERG | 3 | 12 | |||

| 6 | 2 | EST | NOVIA | 2 | 10 | |||

| 6 | 2 | EUR | GARIA | 2 | 10 | |||

| 6 | 2 | EVA | HALIA | 2 | 10 | |||

| 6 | 2 | RO | HEIT | 2 | 8 | |||

| 6 | 2 | VE | WALD | 2 | 8 | |||

| 6 | 2 | NI | INIA | 2 | 8 | |||

| 4 | 2 | RO | IN | 4 | 8 | |||

| 4 | 2 | VE | KA | 3 | 6 | |||

| 4 | 2 | NI | SIA | 2 | 6 | |||

| 4 | 2 | NO | ZIA | 2 | 6 | |||

| 4 | 2 | LE | INA | 2 | 6 | |||

| 4 | 2 | LI | OVA | 2 | 6 | |||

| 4 | 2 | SC | ICA | 2 | 6 | |||

| 4 | 2 | ST | THA | 2 | 6 | |||

| 4 | 2 | FL | INE | 2 | 6 | |||

| 4 | 2 | FR | ICH | 2 | 6 | |||

| 4 | 2 | DA | ARK | 2 | 6 | |||

| 4 | 2 | YU | LI | 2 | 4 | |||

| 4 | 2 | UL | NO | 2 | 4 | |||

| 4 | 2 | OR | RO | 2 | 4 |

From this list it’s possible to connect the beginnings and endings to create new names. Below are just 60 of the 2500 names you can create this way, some quite plausible, others just fun to roll of the tongue. My favorites so far? I like Beria, but it’s already been taken by a historical figure. Balonia is pretty tempting. Drekia and Drearia are a pretty good pair (that probably would get mixed up like Slovenia and Slovakia). Euroslavia and Euristan form nice juxtapositions. Cornia and Krania are nicely corporeal. Krakistan and Peroslavia are also somehow evocative. Right up there is Evakistan (which includes in its name the suggestion of hurried departure), but the best, I think, is Betonia, which captures the experience of concrete tower-block suburbs better than anything else I have seen. So next year I’ll set my students to write the history of Betonia. Perhaps they’ll have to deal with an Elbonian invasion.

- ALATONIA

- BALERIA

- BALONIA

- BALTONIA

- BERIA

- BEROVIA

- BETONIA

- BORROSLAVIA

- BRAKISTAN

- BRAVIA

- CARPACARPATHIA

- CARPAGARIA

- CARPARIA

- CHARIA

- CORKISTAN

- CORNIA

- DREARIA

- DREKIA

- DRETONIA

- DREVIA

- ESTRIA

- ESTROSLAVIA

- EURANIA

- EURISTAN

- EUROSLAVIA

- EURURIA

- EVAKISTAN

- GRANGARIA

- GRANISTAN

- HOHENHEIT

- KARENIA

- KARGARIA

- KARISTAN

- KARKISTAN

- KARLOVAKIA

- KARLTONIA

- KRAKISTAN

- KRANIA

- KRATONIA

- LATHIA

- MANOVIA

- MARANIA

- MARONIA

- MARROSLAVIA

- MENIA

- METONIA

- MOLTONIA

- PEKISTAN

- PEROSLAVIA

- PONIA

- POTTLAND

- POTTURIA

- SATONIA

- SLANOVIA

- SLARANIA

- SLATONIA

- SLAVANIA

- SYLIA

- SYLKISTAN

- SYLSYLVANIA

- TRANSISTAN

- TRANSOVAKIA

| ALATONIA |

| BALERIA |

| BALONIA |

| BALTONIA |

| BERIA |

| BEROVIA |

| BETONIA |

| BORROSLAVIA |

| BRAKISTAN |

| BRAVIA |

| CARPACARPATHIA |

| CARPAGARIA |

| CARPARIA |

| CHARIA |

| CORKISTAN |

| CORNIA |

| DREARIA |

| DREKIA |

| DRETONIA |

| DREVIA |

| ESTRIA |

| ESTROSLAVIA |

| EURANIA |

| EURISTAN |

| EUROSLAVIA |

| EURURIA |

| EVAKISTAN |

| GRANGARIA |

| GRANISTAN |

| HOHENHEIT |

| KARENIA |

| KARGARIA |

| KARISTAN |

| KARKISTAN |

| KARLOVAKIA |

| KARLTONIA |

| KRAKISTAN |

| KRANIA |

| KRATONIA |

| LATHIA |

| MANOVIA |

| MARANIA |

| MARONIA |

| MARROSLAVIA |

| MENIA |

| METONIA |

| MOLTONIA |

| PEKISTAN |

| PEROSLAVIA |

| PONIA |

| POTTLAND |

| POTTURIA |

| SATONIA |

| SLANOVIA |

| SLARANIA |

| SLATONIA |

| SLAVANIA |

| SYLIA |

| SYLKISTAN |

| SYLSYLVANIA |

| TRANSISTAN |

| TRANSOVAKIA |

Work in progress: Thinking about cleavages, part IV

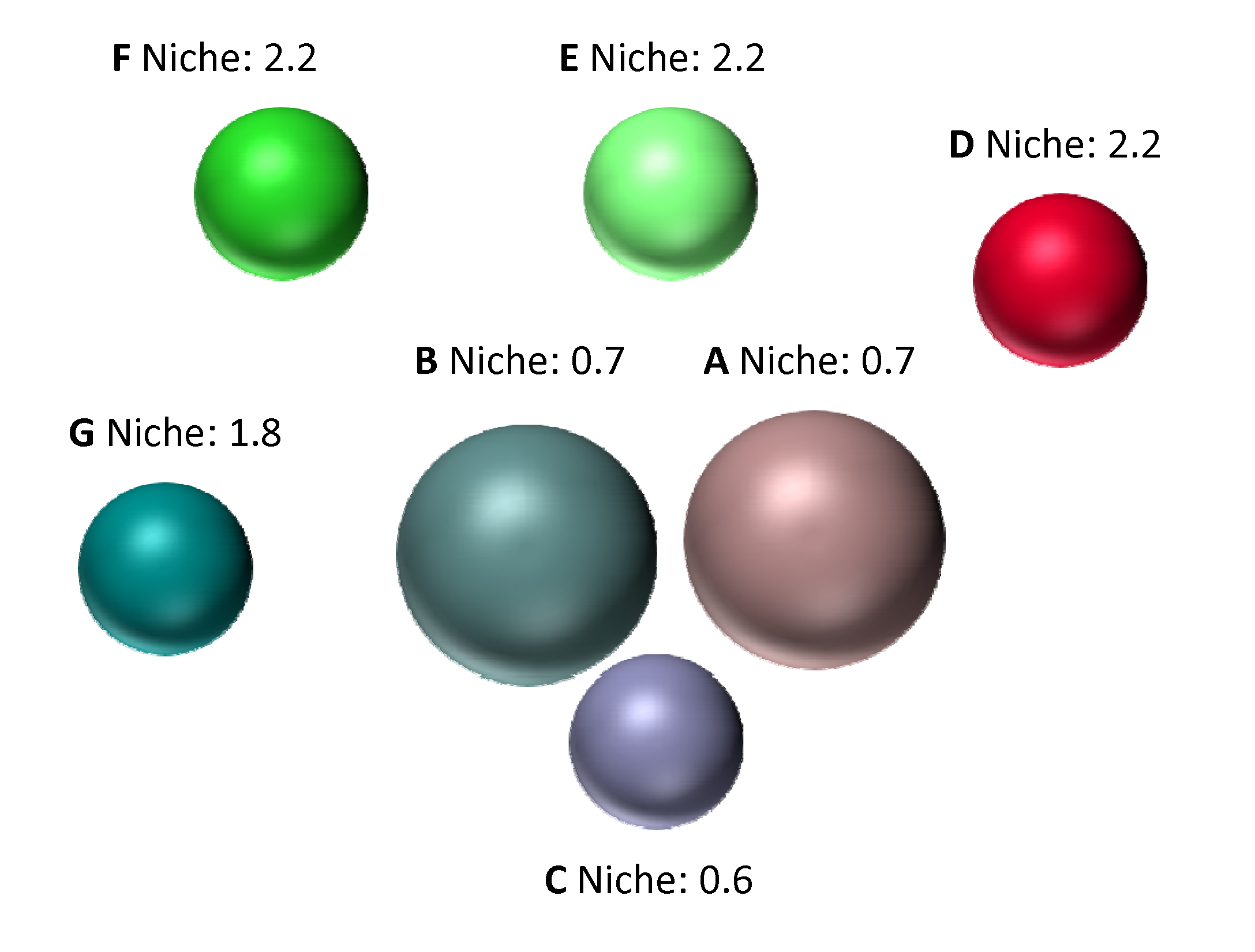

![]() The last post pointed toward a successor that would talk more about dimensions of competition, emphasizing the “non-primary” dimensions. This allows some attention to the emerging question of “niche” parties and points directly to the question of salience that I promised would follow. From this we can then look at the links between the kinds of conflicts and their roots in society (or lack thereof).

The last post pointed toward a successor that would talk more about dimensions of competition, emphasizing the “non-primary” dimensions. This allows some attention to the emerging question of “niche” parties and points directly to the question of salience that I promised would follow. From this we can then look at the links between the kinds of conflicts and their roots in society (or lack thereof).

And one final preliminary note: what follows is far longer and more detailed than anything I intended. The material here pushed itself in this direction and I merely hung on for the ride.)

The analysis in the previous post suggested a fairly wide consensus about the relatively narrow degree of dimensionality in most polities: something more than one dimension, but rarely more than two dimensions, at least not two dimensions of significance equal to the first. What scholars find in most cases–whether they use manifesto data or expert survey data–is configurations that consist of one dominant dimension of conflict along with one or more subordinate dimensions, (analogous to the “one and two-halves party system” metaphor discussed with some disdain by Sartori (1976, 168) or perhaps metaphorically akin to the higher dimensions in string theory which are curved tightly in on themselves). The primary dimension is most often but not always socio-economic. The number, type and strength of non-primary dimensions vary rather significantly from country to country (and, Stoll [2010] would suggest, over time).

The question is how we should handle these various dimensions in scholarly analyses. The major dimension(s) provide(s) a challenge in their composition, in how many issues they bundle. Bakker’s work suggests that in most Western European countries the economic dimension bundles in the GAL-TAN dimension bundle whereas in some (especially Greece and Austria) it does so to a much smaller degree. In postcommunist Europe, by contrast, the overall tightness of the bundling is somewhat lower (both mean and median correlations between economic and GAL-TAN positions are lower by about 0.10).

For the dimensions beyond the primary conflict, problems of definition are different and there are questions of measurement and significance. These secondary and tertiary dimensions are clearer in that they bundle fewer issues, but our everyday vocabulary–and even our scholarly vocabulary–is ill-equipped to deal with these dimensions and the parties that occupy them.

Perhaps the most significant evidence of this inadequacy is the recent emergence of the notion of the “niche” party into active scholarly consideration. A slightly-more-than cursory search of electronic sources suggests that this term has shifted over time from a rather idiosyncratic and descriptive term toward a theoretically-grounded concept.

The etymology of the term “niche” is little help, deriving from the architectural term for “a recess for a statue”(OED http://www.oed.com/?authRejection=true&url=%2Fview%2FEntry%2F126748) into a variety of meanings that imply removal, seclusion, and a general notion of “apartness.” During the past century ecologists have transformed the word into a metaphor of suitability: every living thing has a “niche” outside of which it is not as fit for survival.

Nor does the phrase “niche party” have a long history that would offer suggestions on how it is best to be used. The phrase does not to have been in common use before the early 1990’s, with no mentions at all in the Lexis-Nexis Academic Universe or Google Books databases before 1993. The early uses of the term appear between 1993 and 1999 tend to apply to small parties in systems with two or three dominant parties: the Progressive Democrats in Ireland, the New Democratic Party in Canada, the Ethnic Minority Party and Christian Heritage Party in New Zealand, and Shas in Israel.

Gallagher in 1993 characterizes a “‘niche’ party” as “looking for support from certain groups” and contrasts this strategy with that of a “catchall party” (66, http://bit.ly/ktoN6Q). A later commentator from New Zealand extends this metaphor directly into the realm of aquaculture:

[Green Party co-leader Rod Donald] used “a fishing analogy to describe the difference between a broad-spectrum party and a niche party. The former “‘trawl” to catch as many voters as possible, while the latter use a more selective long line. (Luke, Peter. 1999. “Push-button parties.” The Press. 23 October, section 1, p. 11.)

Niche parties are thus somehow distinctive, small, and unlikely to get much bigger. Beyond these core characteristics, however, the precise identification of niche parties becomes more difficult and the boundaries between definitional and empirical limits begins to blur. More recent definitions help to narrow down the field, but they do not necessarily agree.

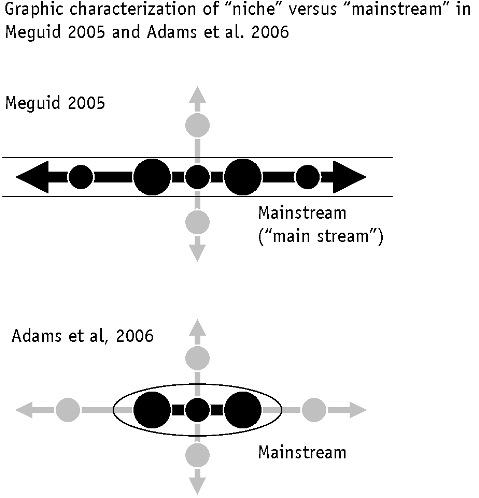

Perhaps the most specific of the recent definitions is the one provided by Meguid in her meticulous 2005 analysis of the interaction between “niche” and “mainstream” parties. It is notable, first, that Meguid defines “niche” against “mainstream” rather than “catchall,” suggesting that the difference lay not (solely) in the way a party seeks to attract its voters but rather (also) in its position within the broader party system. “Niche” here means “away from the main”

Her definition involves three distinct aspects dealt with here or in previous (or future) posts on this topic: voter base, issue dimension and the degree of issue bundling

First, niche parties reject the traditional class-based orientation of politics. Instead of prioritizing economic demands, these parties politicize sets of issues which were previously outside the dimensions of party competition… [T]hese parties … challenge the content of political debate.

Second, the issues raised by the niche parties are not only novel, but they often do not coincide with existing lines of political division. Niche parties appeal to groups of voters that may cross-cut traditional partisan alignments.

Third, niche parties further differentiate themselves by limiting their issue appeals. They eschew the comprehensive policy platforms common to their mainstream party peers, instead adopting positions only on a restricted set of issues. Even as the number of issues covered in their manifestos has increased over the parties’ lifetimes, they have still been perceived as single issue parties by the voters. Unable to benefit from pre-existing partisan allegiances or the broad allure of comprehensive ideological positions, niche parties rely on the salience and attractiveness of their one policy stance for voter support. (Meguid 2005, 347-348)

Adams et al (2006) accept some of these restrictions but not all of them. Their definition focuses on ideology but rejects the need for a cross-cutting ideological dimension or the abandonment of class politics. Instead they accept as “niche” those

party families who present either an extreme ideology (such as Communist and extreme nationalist parties) or a noncentrist “niche” ideology ( i.e., the Greens). (Adams et al, 2006, 513, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3694232 .)

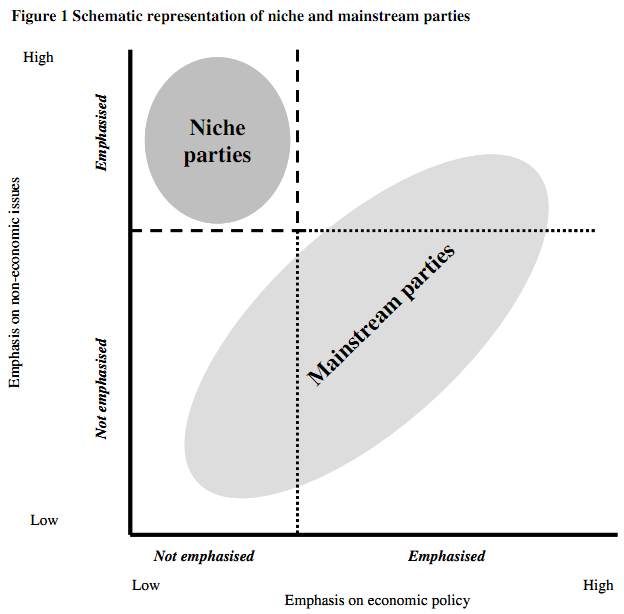

The key underlying factor for Adams et al thus appears to be some kind of distance from the dimensional segment defined by the main parties; niche parties are either in the same plane as the main competition but some distance from the nearest competitor on its side, or they are some distance away from the main dimension on a secondary or tertiary dimension. Graphically, the difference between Meguid and Adams et al looks something like this:

Removing the restrictions on the main dimension of competition/class-based appeals is significant. It minimizes the question of dimensionality, replacing it with proximity (“extreme”, “non-centrist”), and also eliminates Meguid’s demographic limitations that exclude class-based parties from the “niche” category.

Wagner offers a simplified version of Meguid, defining “niche parties” as those “that de-emphasise economic concerns and stress a small range of non-economic issues”(2011, 3, http://homepage.univie.ac.at/markus.wagner/Paper_nicheparties.pdf)

Wagner’s analysis lends itself to an elegant graph that defines niche parties in strictly economic terms and places in the mainstream any party that either emphasizes economic issues or avoids non-economic issues:

Wagner’s definition thus sets aside any notion of the demographic basis of class competition (potentially opening the door to Communist parties) but it also removes the degree of extremeness of a party’s position in favor of a pure reliance on emphasis (excluding Communist parties from a different direction). The simplification allows him to address and measure the “niche-ness” of specific parties rather than assuming it based on a party’s “family” which may for an individual party be a poor fit (Bresanelli 2011 finds a fairly large number of parties whose manifestos do not match well with those of others in their European Parliament group, with the share of such parties particularly high in postcommunist Europe, http://euce.org/eusa/2011/papers/6f_bressanelli.pdf). Wagner’s party-specific measure also accommodates changes over time to and from the “niche” category as parties pick raise or lower their economic and non-economic emphases. This more nuanced analysis has its limitations: Wagner establishes economic policy as the only dimension used for distinguishing mainstream from niche, and he establishes binary cut-off points for economic and non-emphasis. Even here, however, he suggests some flexibility: he acknowledges both the possibility of a scalar alternative to the binary cutoff points, and he suggests the possibility of a non-economic variant for “party systems in some countries are defined more strongly by, for example, ethnic divisions” (9)

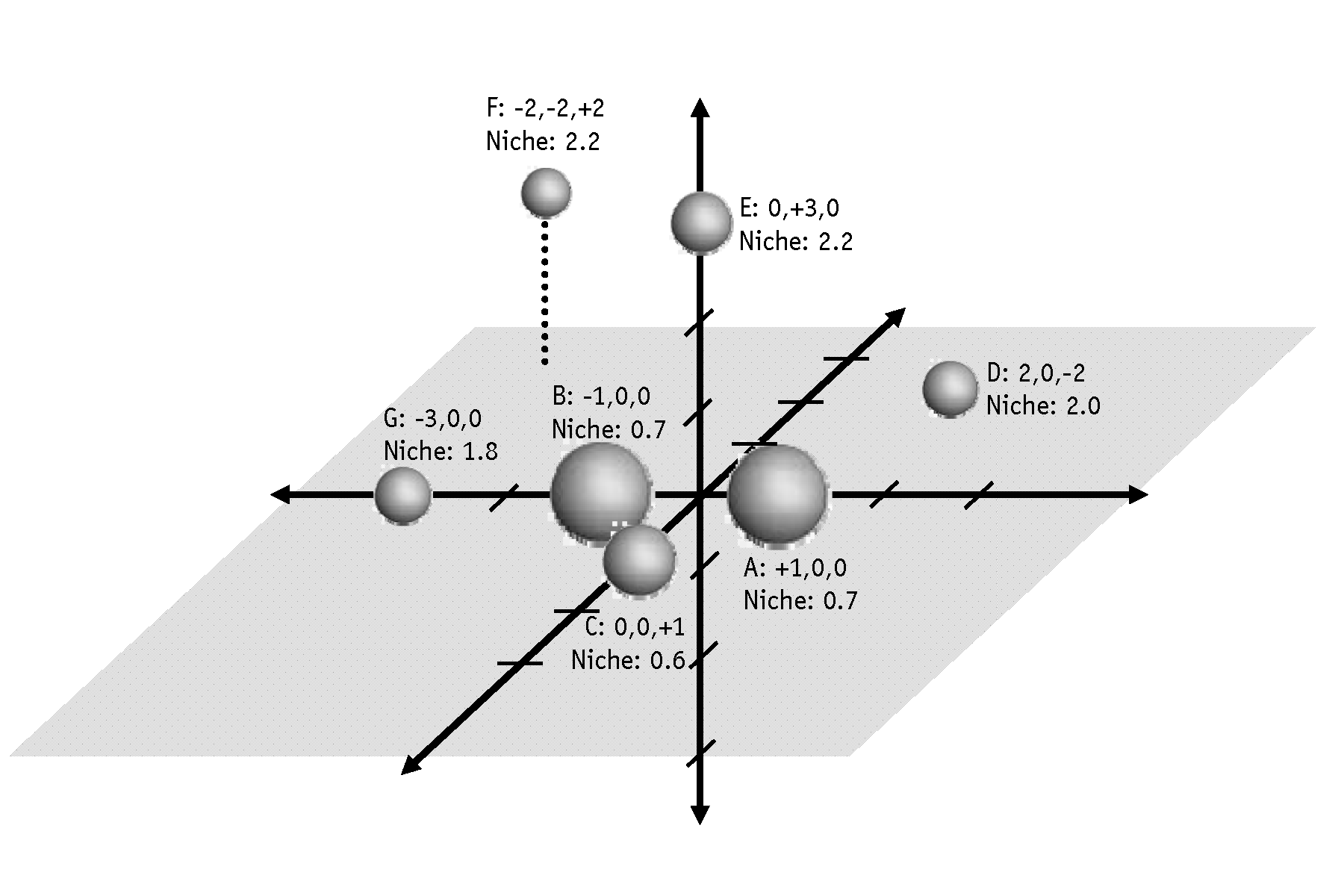

An even more recent piece by Miller and Meyer offer an alternative that strengthens Wagner at its weakest points: the binary distinction and the lack of attention to alternative dominant dimensions (2011, http://staatswissenschaft.univie.ac.at/uploads/media/Miller___Meyer_-_To_the_Core_of_the_Niche_Party.pdf). Miller and Meyer define “niche parties”as those that “compete by stressing other policies than their competitors“(4) or, according to another formulation in the paper, “A niche party emphasizes policies neglected by its rivals”(5). They operationalize this relatively simple definition with a measure that “compares a party’s policy profile with the (weighted) average of the remaining party system” across multiple dimensions (11). In the process they depart from Wagner’s use of the economic dimension as a baseline for “the mainstream”: “We conclude that – while economic niches might be rare – to exclude them by definition unnecessarily restricts the concept”(8). The formula also generates a scale which allows comparison of parties according to the “degree of nicheness.”

The formula is intuitive and easy to grasp. The farther a party is from all other parties on a given dimension–in terms of emphasis, it must be remembered, and not policy position–the higher is the niche score for its position on that dimension. The more niches its positions on a variety of issues, the more it can be considered a niche party. My first attempt to give a visual picture of how distances translate into niche positions is the spatial approach below:

This is misleading,however, because we are used to reading these kinds of graphs as representing positions whereas in this case they represent intensities. It is therefore useful (and more fun) to reconceptualize the map in terms color, with each party’s emphasis translating into a score on 3 color dimensions: red, blue and green. In this case the intensity of color is roughly analogous to difference from the center (which would be flat grey). Bright in this case equals “nichy.”

This is misleading,however, because we are used to reading these kinds of graphs as representing positions whereas in this case they represent intensities. It is therefore useful (and more fun) to reconceptualize the map in terms color, with each party’s emphasis translating into a score on 3 color dimensions: red, blue and green. In this case the intensity of color is roughly analogous to difference from the center (which would be flat grey). Bright in this case equals “nichy.”

Party A and B occupy opposite positions on a single issue dimension (which could be taken here to be the “main” one except that this method does not identify a “main dimension”) and are low-emphasis on all the others. They thus have quite low niche scores and are quite grey. Party C’s niche score is even lower because it is likewise low-emphasis on all issues except one and (thanks to parties A, B and G, it is relatively close to the mean on that one issue. Parties D, E, F, and G all have unbalanced emphasis in their own way, either on one issue (E and G) or two (D) or all three (F) and are therefore brightly colored. It is noteworthy here that while starting closer to Meguid’s notion of dimensionality than to that of Adams et al, Miller and Meyer end up allowing niche status to parties on any dimension of competition as long as it sufficiently different from the emphasis of other parties.

Party A and B occupy opposite positions on a single issue dimension (which could be taken here to be the “main” one except that this method does not identify a “main dimension”) and are low-emphasis on all the others. They thus have quite low niche scores and are quite grey. Party C’s niche score is even lower because it is likewise low-emphasis on all issues except one and (thanks to parties A, B and G, it is relatively close to the mean on that one issue. Parties D, E, F, and G all have unbalanced emphasis in their own way, either on one issue (E and G) or two (D) or all three (F) and are therefore brightly colored. It is noteworthy here that while starting closer to Meguid’s notion of dimensionality than to that of Adams et al, Miller and Meyer end up allowing niche status to parties on any dimension of competition as long as it sufficiently different from the emphasis of other parties.

In practical use, this measure still exhibits a certain degree of awkwardness. In particular it appears to be highly sensitive to number and type of dimensions used for calculating the overall niche scores. Miller and Meyer use party manifesto data arranged in well-defined categories for Western Europe which appears to serve them well (I cannot judge at first glance), but for Eastern Europe where manifesto data is notoriously problematic, this method might not work as well (and it certainly depends in Miller and Meyer’s case on the not-always-accurate assumption that the sheer amount of verbiage translates into emphasis). The method should, in theory, be usable with expert survey data on the salience of issues for particular parties, but these vary substantially in terms of what “dimensions” they ask about. As a result, the results for “niche-ness” of particular parties can differ, even in relatively stable party systems. The two tables below present results of my preliminary calculations for the two countries I know better than others using the available expert survey data on emphasis. The results are extremely consistent for some parties and quite different for others, particularly those with some “niche” characteristics or others.

Table 1. Niche scores for parties in the Czech Republic based on Expert Surveys

| Party | Expert Surveys | Overall | My own assessment | ||||

| 2002 Eurequal | 2006 North Carolina | 2007 Eurequal (evaluated dimensions) | 2007 Eurequal (policy areas) | ||||

| CSSD | -0.2 | -0.3 | +0.1 | -0.1 | Mainstream through intermediate | Mainstream | |

| KDU-CSL | +0.1 | +.6 | -0.2 | +0.1 | Mainstream through niche | Interesting question | |

| KSCM | -0.1 | +0.2 | -0.1 | +0.4 | Intermediate through niche | Interesting question | |

| Nezavisli | – | -0.1 | – | – | Intermediate | ||

| ODA | +1.1 | – | – | – | High | ||

| ODS | -0.3 | +0.0 | -0.0 | -0.2 |

|

Mainstream | |

| SNK-ED | – | -0.8 | – | – | Mainstream | ||

| SZ | – | -0.1 | +0.5 | +0.8 | Intermediate to niche | Interesting question | |

| US | +0.4 | – | – | – | Intermediate | ||

Table 2. Niche scores for parties in Slovakia based on Expert Surveys

| Party | Expert Surveys | Overall | My own guess | |||

| 2002 Eurequal | 2006 North Carolina | 2007 Eurequal (evaluated dimensions) | 2007 Eurequal (policy areas) | |||

| ANO | +0.7 | – | – | – | Niche | |

| HZDS | -0.4 | -0.8 | -0.5 | -0.4 | Mainstream | Mainstream(at first) |

| KDH | +1.1 | +0.4 | +0.6 | +0.0 | Intermediate through niche | Intermediate through niche |

| KSS | -0.0 | +0.1 | – | – | Intermediate | Interesting question |

| PSNS | -0.1 | – | – | – | Intermediate | Interesting question |

| SDKU | +0.1 | +.01 | +0.0 | +0.5 | Intermediate through niche | Mainstream through intermediate |

| SF | – | -0.6 | – | – | Mainstream | |

| Smer | -0.3 | -0.5 | +0.2 | +0.2 | Mainstream through intermediate | Mainstream |

| SMK | -.01 | +0.7 | +0.2 | -0.1 | Intermediate through niche | Niche if there ever was one |

| SNS | +0.2 | +0.7 | +0.0 | -0.1 | Intermediate through niche | Interesting question |

Used here the method does a fairly good job identifying parties that are clearly mainstream by any reckoning–the Czech ODS and CSSD and the Slovak Smer–but for other parties there is significant disagreement, and many of the parties producing the sharpest disagreements are those that defy easy non-quantitative categorization.

- Green parties: The Green party would be considered “niche” by both Meguid and Adams et al and falls into that categorization in both measures of the 2007 Eurequal survey but not in the 2006 North Carolina survey, in large part because the North Carolina survey simply does not have a measurement of environmental questions and so its niche-ness comes out only on lifestyle and ethnic minority questions.

- Communist parties. Both the Slovak and Czech communist parties (the unreconstructed ones rather than their social democratic successor parties) emerge as slightly but not overwhelmingly more niche-like than other parties. That such parties are an open question corresponds well with the disagreement between Meguid and Adams et al about whether to include them in the niche category.

- Christian Democratic parties. While not included in either Meguid or Adams categories, such parties in postcommunist Europe (and in certain parts of Western Europe, particularly Scandinavia) often appear to operate by many of the principles specified by Meguid: avoiding class based appeals (they did this from early on), taking up issues off the main issue dimension (church and morality issues are not the main dimension in most of these countries), and keeping a relatively narrow range of issues, though they did at least claim to take positions across all of the major issue areas. Both the Slovak and Czech Christian Democrats put a foot in the niche category and in the 2002 survey Slovakia’s Christian Democratic Movement receives the highest niche score of any party in the survey. At the same time it (and its Czech counterpart) show few niche qualities at all in the 2007 Eurequal survey long version, because their distinctive stands on lifestyle issues are diluted by an extremely large number of economy-related questions in the survey.

- Ethnic minority parties. Slovakia brings three additional parties into the niche debate, all of which made strong ethnic-based appeals. The most clearly niche-like party of these three–indeed perhaps of all the parties listed in the two tables above–is SMK (the Party of the Hungarian Coalition)–a party with an almost purely ethnic Hungarian voting base and no major policy issues beyond minority rights and related issues. Yet this party produces a high niche score only in the 2006 North Carolina survey which has three questions (out of a total of twelve) on nationalism, ethnic minorities, and decentralization. The same survey suggests an equally high niche score for the SNS (the Slovak National Party) which takes diametrically opposed but equally emphatic positions on the same issues.

- Liberal parties. Finally, there is the question of liberal parties. These are often small parties, sometimes with relatively narrow issue emphases, but because in Western Europe they tend to compete on the main issue dimensions, they rarely fall into the niche category and are not included either by Meguid or Adams. In Slovakia and the Czech Republic, however, they often appear to fall into this category. The Czech party US (Freedom Union) received a positive niche score in because of its position on social rights (matched and countered by its election coalition partner, the Christian Democrats) and another liberal party, ODA received one of the highest niche scores on the 2002 Eurequal survey (though largely because the party was by then moribund and received low salience scores on nearly every question. In Slovakia, one small liberal party returned extremely mainstream scores (SF, Free Forum) but two others returned scores that were mixed on the niche side (SDKU, the Slovak Democratic and Christian Union) or strongly niche-like (ANO, the Alliance of the New Citizen) on the basis of social rights questions which in Slovakia (as in the Czech Republic) are not a high salience issue when compared to others.

Even if this application of Miller and Meyer’s formula in this form and with this data does not (yet) provide a fully reliable measure, their standard for measuring niche parties does gets at the key issues of “niche-ness” in Central Europe and helps us think more clearly about politics in the region.

Meguid took a helpful first step with her attention to secondary and tertiary issue dimensions, and Wagner and Miller and Meyer add a useful emphasis on issue salience that edges into areas of issue ownership. One way to think about what politics is “about” in a particular country is to look at what the main political forces fight about and what other political forces “fight to fight about” turning political debate onto some other topic where they are strongest. From Schattschneider and Riker through contemporary scholars such as Green-Pedersen, there has been a strong current of emphasis on the meta-struggle about the issues over which we struggle. In this sense we might regard niche parties simply as those that achieve limited success in the herasthetic realm. They neither fail so badly that they gain no voters nor succeed so well that their issue dimension becomes the dominant one. Or (since according to Miller and Meyer this sort of “niche-ness” is not static), they may be simply passing through from one of these extremes to another. Niche parties thus call our attention to the partial dimensions that surround the main conflict, the asymmetrical battles between one party and all the rest. They can be characterized as positional conflicts between two rival policies, but it may be better to characterize them as conflicts of attention between parties that do not care and parties that do. So it is little surprise (in retrospect) that such parties behave differently from others since their struggle is not to attract voters to a position but rather to attract voters’ attention to that position and hold it there.

In a sense it could be argued that all parties seek to do this, even on main dimensions. So called mainstream parties seek out the niches within the main stream as they try to attract attention to a specific aspect of the issue where they hold the advantage: Party A’s reputation for lowering taxes versus Party B’s reputation for improving services (Colomer and Puglisi 2005). It is not clear to me whether this is qualitatively different from the kind of effort undertaken by niche parties, but it does seem different to the extent that the two issues are bound up in the minds of voters: if lowering taxes and improving services are inextricably linked in most voters’ minds, then Party A’s appeals to its own area of strength cannot but cast some attention to the rival strength of Party B. It may be for this reason that a considerable part of party effort may be in this linking or de-linking of issues to one another. If Party A can argue successfully that the level of taxation has nothing to do with the quality of service, then it can create for itself a “niche”–and because it is a niche within the main stream of political life, where voters are already passionate and attentive, it may hold the key to political majority. For less-discussed, less-salient issues, an equally persuasive effort at projecting issue ownership will net fewer voters and so niches outside of the mainstream, and so such a party must expend its effort not only to persuade that its position is right, and not only that it is the best party to advance that position, but also that the position matters in the first place. So we should expect niche parties to be different from other parties.

But perhaps by the same token we should expect niche parties to be different from one another, because some of these partial dimensions, secondary and tertiary dimensions may have fundamentally different characteristics from others. And here it is necessary to raise the slippery question of demographics. Demographic characteristics are admittedly less solid than they look. Questions on public opinion surveys separate respondents into rigid, well-defined categories that seem relatively permanent but even once solid fixtures like class and religion are now in seemingly permanent definitional flux, and as with attitudes, the role of demography in political decision-making depends not only on an individual’s characteristics but on the salience of those characteristics in political struggle. And salience is not the only fluctuating element. A key element of demographic (and attitudinal) determinants of politics is the sense of mutual-recognition and groupness among those who share them. These are often overlooked (perhaps because they are not easily quantified) but play a major role in shaping their importance. Political decisions are not always made by individuals who participate in groups; they sometimes emerge within groups and capture the allegiance of the individuals involved. That allegiance, like the demographic characteristics themselves, may be sticky, and may produce fairly high barriers between “in” and “out.” And here, finally, is where niche parties come in. Those whose partial issue dimensions depend on individual sentiment and loose attitudinal configurations should behave quite differently from those that stem from hard-to-change characteristics and mutually reinforcing social circles. Both must constantly fight for the salience of their chief position; only some will do so by encouraging group identity and interconnection.

It is this latter consideration that now causes me to wonder a bit about the wonderful work by Meguid, Wagner and Miller and Meyer. In one sense it exactly what we need: serious research about partial dimensions and their empirical dimensions and dynamics. In another sense, though, it may be a misnomer to talk about this in terms of “niches.” I am struck by a passage of Miller and Meyer which notes that “Niche parties do not have their nicheness carved in stone”(2011, 8) and the contrast between this interpretation and the original meaning of niche which was by definition something carved in stone. Of course etymology is not destiny, but there is something relevant about the carved-in-stone-ness of certain party positions. Niche parties may all shift political competition to questions more relevant to their own programmatic strength, but there is a fundamental difference between greens and majority nationalists on the one hand and ethnic or religious minorities on the other. The latter come as close as possible to the architectural metaphor of a niche: the recesses are deep and the walls around them quite thick and hard-to-penetrate. Of course the same can also be said for some Communist Parties, which may explain their inclusion in the work of Adams et al. Compared to these, majority nationalists or greens or cultural liberals (in Central and Eastern Europe at least) do not fit the same profile, do not face the same advantages in holding a well-defined voting base or the same difficulties in trying to expand.

This analysis suggests two different dimensions, producing three categories of niche party:

| Issue Centrality | |||

| Primary Dimension, Full |

Secondary/Tertiary Dimension, Partial |

||

| Group closure | Low | Social Democrats Conservatives Liberals |

Greens Majority nationalists Some social liberals |

| High | Communists Some Christian democrats |

Ethnic minorities Religious minorities Some Christian democrats |

|

Some parties qualify as niche by either standard–they have both a high degree of group closure and a non-central issue. Of the remainder, some exhibit only collectivity or identity niches but remain on the central dimension of competition, while other occupy (potentially less enduring) issue niches without a sense of group identity or commonality beyond the issue at hand.

This question needs more work that is not strictly relevant for my immediate purpose, so I will come back to it in future posts. In the meantime, this discussion of niche parties leads directly into the last two topics I want to discuss in this “work in progress” series: issue salience and ownership and parties’ demographic and collective ties. But more on those in a few days.

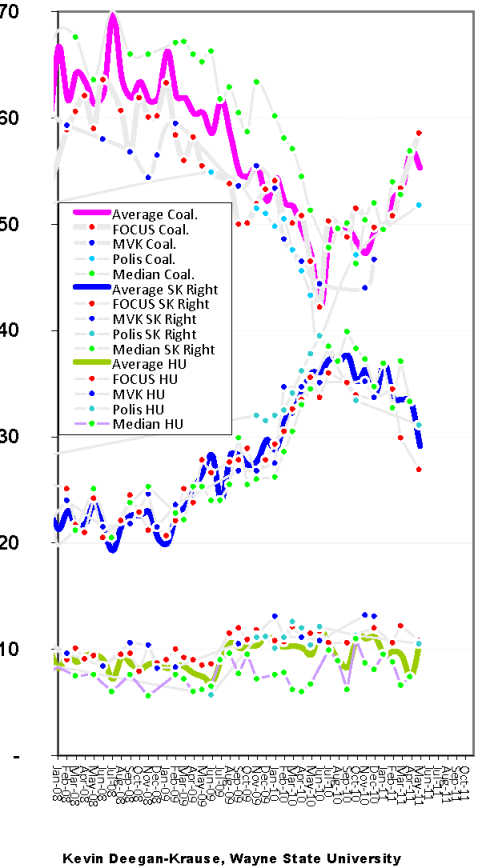

Slovakia Dashboard News, May 2011: In the Direction of a Majority?

Big poll yesterday from FOCUS and I’m trying to get back into the habit of updating these posts when big polls come out, so here goes a try at a quick review of recent public opinion polling events.

Big poll yesterday from FOCUS and I’m trying to get back into the habit of updating these posts when big polls come out, so here goes a try at a quick review of recent public opinion polling events.

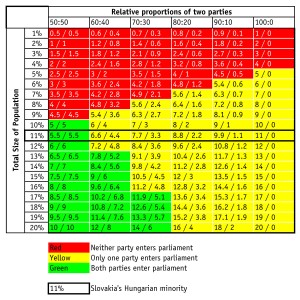

The big picture is, as it has been in the past 12 months, a shift away from the government coalition toward the opposition, a shift that has cost the coalition 10 percentage points over the last year and benefited the parliamentary opposition–especially Smer–by about the same amount. The pattern is an almost mirror image of the last months of the 2006-2010 Fico government, though (as the graph below shows) slightly shallower. With this month’s polling results, put the current coalition and opposition and opposition almost exactly where they were in January 2010, just six months before the election.

As I noted previously, this can’t be good news for the Radicova government or bad news for the opposition–especially Fico’s Smer–but it is interesting to think how pleased the then-opposition was in January 2010 about its gains in the previous year. Of course now it’s in the same numerical position and sliding.

As before, the other noteworthy point is the internal composition of the coalition and opposition according to these polls. Compared to January 2010, Smer has strengthened at the expense of SNS and HZDS. Within the current coalition, the party strengths have remained surprisingly stable, and the drop has come largely from the ebb in support for SaS, which is not unpredictable but a bit worrisome for the coalition since its current majority would have been impossible without a new party to woo to the polls those secular pro-market voters who were disillusioned with Dzurinda’s SDKU.

Since I am moving now into individual parties, it is relevant to talk about some significant points in the month’s new data:

Parties Below the Threshold:

So one month after describing HZDS and MKP-SMK as “perennials in decline” both parties demonstrate a recovery. Neither is back above the threshold, and neither is likely to be (except in coalition with somebody else) but they are not in free fall. For both parties it is notable that two very different polls show parallel patterns of stabilization (for MKP) and slight rise (for HZDS), but also that the absolute levels are very different. For HZDS, the Median polls have been consistently about a point higher than those of FOCUS, whereas for MKP it is the FOCUS polls that show results a stable 2+ points higher. The firm Polis has only issued results of one poll this year, in early May, so we do not have a closer trendline, but the overall results are in line with the other polls: for MKP-SMK Polis has tended over time to find a middle level and does so again (an almost perfect mathematical mean of FOCUS and Median); for HZDS, Polis tends to find lower results than other polls (and in this proved the most accurate in the 2010 election) and it does so again in May with a result of 2.5. A few more Polis polls would help the trendline, but it does not seem to be in their current plan.

The New Parties:

As may perhaps be expected of new parties with less stable electorates (though in retrospect that is simply conjecture and not something I know to be true from any research), Most-Hid and SaS have shown considerable change over time and almost random differences among polls.

All three recent polls put Most-Hid between 5 and 7 percentage points, but the range and patterns vary: FOCUS polls show a sharp decline from last month which was a sharp rise from the month before (suggesting a certain amount of noise around the 6% mark); Median polls show a drop and recovery. Polis shows stabilization around 7% but with few monthly polls to show any recent pattern.

The decline of SaS has begun to look more serious. A high result from Median in April contrasted with a low result from FOCUS so it was hard to tell. This month all three polls show a drop, extremely sharp in FOCUS and (especially) Median and significant for Polis (which had shown the significant drop already late last year). Given its current level and trajectory, the party will need significant positive news not to fall below the electoral threshold in one of the next two or three polls and produce the headline “SaS falls from parliament” which can itself encourage further out-migration. Will its voters go to SDKU or to yet another new party?

The decline of SaS has begun to look more serious. A high result from Median in April contrasted with a low result from FOCUS so it was hard to tell. This month all three polls show a drop, extremely sharp in FOCUS and (especially) Median and significant for Polis (which had shown the significant drop already late last year). Given its current level and trajectory, the party will need significant positive news not to fall below the electoral threshold in one of the next two or three polls and produce the headline “SaS falls from parliament” which can itself encourage further out-migration. Will its voters go to SDKU or to yet another new party?

The Small Perennials

Among the small but enduring parliamentary parties there is often not much to say. This month is not much of an exception.

KDH tends to float between 8 and 10. It is coming off a recent bulge last year when it moved above 10 for awhile, but now it is back down below 10. There has been a bit of noise here: FOCUS put it below 7 last month but now has it back near 10. Median has shown it consistently around 10. Polis, showed a sharp drop last year and has it below 7. The real answer is probably around 8 or 9, but that’s been the best guess for KDH for about the last 17 years whether one reads polls or not.

KDH tends to float between 8 and 10. It is coming off a recent bulge last year when it moved above 10 for awhile, but now it is back down below 10. There has been a bit of noise here: FOCUS put it below 7 last month but now has it back near 10. Median has shown it consistently around 10. Polis, showed a sharp drop last year and has it below 7. The real answer is probably around 8 or 9, but that’s been the best guess for KDH for about the last 17 years whether one reads polls or not.

The overall trajectory of SNS is flat (which is good news for SNS since its trajectory has been one of consistent decline over the last 2 years and since it does not have too far to go before it falls below the 5% threshold). Polls seem to take turns being the outlier. This month the outlier is FOCUS with 8% (last month FOCUS put SNS at 6%). Median has maintained a more consistent level of around 6% in recent months. Polis, which consistently polls low for SNS (though as with HZDS was most accurate in predicting election results) puts it below 5%. The party may gain as voters forget its corruption scandals, but it is not at present built to sustain much more than 5% of relatively extreme voters for whom “the nation” is everything.

The overall trajectory of SNS is flat (which is good news for SNS since its trajectory has been one of consistent decline over the last 2 years and since it does not have too far to go before it falls below the 5% threshold). Polls seem to take turns being the outlier. This month the outlier is FOCUS with 8% (last month FOCUS put SNS at 6%). Median has maintained a more consistent level of around 6% in recent months. Polis, which consistently polls low for SNS (though as with HZDS was most accurate in predicting election results) puts it below 5%. The party may gain as voters forget its corruption scandals, but it is not at present built to sustain much more than 5% of relatively extreme voters for whom “the nation” is everything.

The Large Perennials

There’s no unifying story for the poll results of the two largest parties, so I won’t try to tell one. Polls disagree this month about how much SDKU has dropped, while they all agree that Smer has risen.

SDKU has dropped in all three polls but beyond that there is no consensus. Polis shows a small drop from a high level, keeping the party above 18%. Median shows a slightly larger drop from a slightly lower level, putting the party just below 16%. FOCUS shows a huge drop from about the same level, dropping it to just above 12%. Quite frankly for a party leading an rather fractious coalition this is less of a drop than I would have expected, though they do appear to have solid economic results on their side.

SDKU has dropped in all three polls but beyond that there is no consensus. Polis shows a small drop from a high level, keeping the party above 18%. Median shows a slightly larger drop from a slightly lower level, putting the party just below 16%. FOCUS shows a huge drop from about the same level, dropping it to just above 12%. Quite frankly for a party leading an rather fractious coalition this is less of a drop than I would have expected, though they do appear to have solid economic results on their side.

The big story, of course, would seem to be Smer so it is rather unfair of me to leave it to the end. Smer has made quite a show of raising May poles in recent years and so it is perhaps fitting (if bad punsmanship) to note that in this case the May polls raise Smer, and by significant margins: two points in FOCUS, to 47% four points in Median, also to 47%, and five points (over 6 months) in Polis to 45%. Even more significant, perhaps, is that for once this improvement does not come at the expense of similar parties such as SNS and HZDS, both of which also rose or stabilized this month. Of course Smer is the natural recipient of those discontented with the current government. It has been relentless and extremely effective in its pressure on the government in a whole variety of realms, with multiple and fairly significant social policy critiques each week, constant pressure on the national issue and with battles over the general prosecutor and an impressive ability to join forces with dissenting coalition deputies on particular votes. Smer’s work over the last year demonstrates the potentially of a disciplined, leader-driven party better than almost anything I’ve seen, and poll results in the 40% range should help it to keep that discipline by allowing it to promise the rewards of office after the next election.

The big story, of course, would seem to be Smer so it is rather unfair of me to leave it to the end. Smer has made quite a show of raising May poles in recent years and so it is perhaps fitting (if bad punsmanship) to note that in this case the May polls raise Smer, and by significant margins: two points in FOCUS, to 47% four points in Median, also to 47%, and five points (over 6 months) in Polis to 45%. Even more significant, perhaps, is that for once this improvement does not come at the expense of similar parties such as SNS and HZDS, both of which also rose or stabilized this month. Of course Smer is the natural recipient of those discontented with the current government. It has been relentless and extremely effective in its pressure on the government in a whole variety of realms, with multiple and fairly significant social policy critiques each week, constant pressure on the national issue and with battles over the general prosecutor and an impressive ability to join forces with dissenting coalition deputies on particular votes. Smer’s work over the last year demonstrates the potentially of a disciplined, leader-driven party better than almost anything I’ve seen, and poll results in the 40% range should help it to keep that discipline by allowing it to promise the rewards of office after the next election.

And at present Smer can at least promise the rewards of a solo-government, which must sweeten the deal even more, reducing the worries of some (in the more cosmopolitan/international wing of Smer) about the need for a coalition with SNS. The question, though, is whether Smer will act on the assumption of a solo government and go after the voting base of HZDS and SNS, perhaps only to find itself achingly close to forming its own government but lacking a few crucial votes and no easy partners, or whether it will try something new: either bolstering (or at least not undercutting) SNS to make sure that it returns to parliament, or cultivating potential allies among existing parties such as Most-Hid or KDH, or perhaps cultivating (even covertly seeding) a new party that could fill the gap potentially left by SaS in the next election.

Works in progress: Thinking about cleavages, part III

![]() The last post ended with a comment on the need for understanding the nature of the conflicts and the role of political institutions, but in retrospect that is a bit premature since before I can talk about the tension between the anchoring of conflicts in socio-demographic structures and the manipulation of conflicts by political elites, I need to explore further the nature of the conflicts themselves.

The last post ended with a comment on the need for understanding the nature of the conflicts and the role of political institutions, but in retrospect that is a bit premature since before I can talk about the tension between the anchoring of conflicts in socio-demographic structures and the manipulation of conflicts by political elites, I need to explore further the nature of the conflicts themselves.

In the first post in this series, I raised a series of questions about cleavage-like conflict. The second post tried to lay out the substance of those conflicts, at least as they concern postcommunist Europe. I discussed both the socio-demographic and the attitudinal elements but stopped short of linking them because it is that linkage that is central to much of the controversy about “cleavages” and requires more attention than I had time to give. And I was not really done with the conflict question, as I had not yet dealt with the questions of dimensionality, bundling, asymmetry or … and this may have to wait for yet another day, salience. Here are the potentially problematic issues I raised in the first post:

- The degree to which positions on those issues overlap with one another, and the size of the resulting “bundle” of aligned issues

- The relative distribution of supporters and parties on particular issues or bundles (the degree to which disagreement is symmetrical and continuous or binary and asymmetrical, forming “niches”)

- The degree to which a particular issue or bundle of issues is salient for political debate

In one sense I already started to deal with the question of bundling in the previous post to the extent that, short of arguing that an particular issue is not relevant, the only way to reduce the number of dimensions of analysis is to bundle some issues with others. Of course all “issues” are themselves bundles of specific questions that touch on multiple dimensions. in some cases multiple dimensions of debate may merge (or some may submerge) to form a single dimension of competition, whereas, as Colomer and Puglese note, a seemingly-unidimensional political question can quickly become the subject of a multi-dimensional debate (2006) (The phenomenon is easily observable in the case of the U.S. health care debate in which some Republicans chose to attack the Obama admiminstration’s proposals on financial grounds while others focused on its relationship to abortion and euthanasia).

What emerges as a result is the challenge of measuring dimensionality: how many dimensions shape political competition, and what specific issues do those actually contain. As Budge and Fairlie note, the upper end of the dimensionality scale has “as many dimensions as there are political actors and public preferences held by them – forming an underlying space of almost infinite dimensions therefore”(cited in Colomer and Puglese). The need for clarity, however, calls for the least misleading possible reduction to a relatively small number. At the far end of this process of reduction, is the uni-dimensional conflict between two dominant positions which bundle together everything else (the number of dimensions more or less inversely related to the size of their bundles).

The most common framework for understanding unidimensionality, of course, is “left” and “right.” According to Mair (2007: 208) this framework still ”

appears to offer both sense and shape to an otherwise complex political reality’ at three levels. First, in terms of voters, data from the European Social Surveys conducted in recent years show that more than 80 per cent of voters define themselves as left- or right-wingers. Second, regarding observers and researchers ‘expert surveys’ systematically identify the left-right conflict as one of the most relevant issues in the competition among political parties. Third, with party programmes and electoral platforms, content analysis systematically shows that ‘some form of left-right dimension dominates competition at the level of the parties’ (Mair 2007: 209–210).

But in this dimensional reduction there emerge two significant follow-up questions: what do “left” and “right” actually mean in any particular case? and how much does the left-right dimension capture political competition in any particular country.

As Budge et al note, the positions bundled by “left” and “right” are highly idiosyncratic, differing from country to country and even from one time period to the next in a single country:

“The specific policy position contents of ‘left’ and ‘right’ or of ‘progressive’, ‘liberal’ and ‘conservative’ global ideological positions are accidental.” ‘There is after all no logical or inherent reason why support for peace (for instance) should be associated with government interventionism (also for instance).’ (Budge et al 2001, 13)

The difficulty of finding a unified sense of “left” and “right” is especially difficult in postcommunist Europe where Communist-successor parties pursue pro-market economic reforms (Tavits2009) and where debates over ethnic rights and corruption defy easy categorization into “left” and “right.” Nor do all “lefts” and “rights” easily coincide.

Recent research by Bakker et al (The Dimensionality of Party Politics in Europe, http://www.jhubc.it/ecpr-porto/virtualpaperroom/104.pdf) uses the University of North Carolina expert surveys to assess the correlations between party positions on an economic “left”-“right” scale as well as the Green-Alternative-Libertarian (GAL) versus (Traditional-Authoritarian-Nationalist) scale in which the former receives the label “left” while the latter is considered “right.” They find an average correlation coefficient between the two scales 0.65 and a correlation coefficient above 0.50 in eighteen of the twenty-four European cases they study (EU members except for Cyprus, Malta and Luxembourg) and above 0.75 in nine of the twenty-four, suggesting that a left-right dimension is fairly reliable in many cases. On this measure postcommunist countries actually scored slightly higher than other EU members. A separate analysis of unbundled issues for the same set of countries found multiple dimensions in every country, but most of the twenty-four cases, the strength of the second dimension was well below that of the first, and the ranking of dimensionality in the countries corresponded relatively well to their rankings in the analysis of the hypothesized main dimensions.

Other aspects of their work, however, suggest a degree of caution about a simple left-right framework, particularly in post-communist Europe. First, whereas all non-postcommunist cases yielded a positive correlation coefficient between economic left and “GAL Left,” among the postcommunist cases there was considerable variation: three countries showed a positive correlation (Slovenia, Latvia, Estonia) while seven others produced a negative correlation in which “economic left” coincided with “TAN Right” (Hungary, Romania, Poland, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, and Lithuania) and one case produced no correlation at all (Slovakia) (2010, 6). Only in the first three cases, then, would it be possible to talk about a unidimensional left-right axis, while in the larger group of seven the unidimensionality is difficult to label (is a particular side to be called “left” after its economic aspects or right after its cultural aspects) and in final case the problem does not emerge because there is no dominant dimension.

The analysis also corresponds with the findings of Henjak (West European Politics 2010) and Whitefield and Rohrschneider (and before them, Lijphart, 1999), that while nearly all countries exhibit a fairly significant socio-economic dimension, there is considerable variation in the nature of the secondary and tertiary dimensions. At the risk of going further afield, I will talk about those “other” dimensions in the next post (as promised, actually) before moving on to the question of salience and from there to the conflict-related interaction between voters, party organizations and party positions.

Works in progress: Thinking about cleavages, part II

![]() The last post began what will probably be a fairly discussion of how we should think about “cleavages” in the early 21st century in what we currently call post-communist Europe (a conceptual framework that becomes less relevant every year). I continue that discussion here with attention to one of the questions raised last time: The number and type of issues about which the main actors in the political system compete.

The last post began what will probably be a fairly discussion of how we should think about “cleavages” in the early 21st century in what we currently call post-communist Europe (a conceptual framework that becomes less relevant every year). I continue that discussion here with attention to one of the questions raised last time: The number and type of issues about which the main actors in the political system compete.

Today I simply begin with a list of “things that people say” and some cursory analysis. When scholars who work on Central and Eastern Europe look for the main dividing lines, whether at the level of socio-structural grouping or attitudinal/value difference, what do they tend to find?

Since there is no dominant framework, it is helpful look at commonly-used frameworks to find commonalities in assessments of “cleavage-type” divisions. It is useful to start with broad multi-national assessments before delving into the specifics of individual cases. Lijphart defines seven “issue dimensions of partisan conflict”(Patterns of Democracy, 1999, 79), many of which straddle the distinctions between socio-demographic and attitudinal categories

|

A similar starting point focusing on Central and Eastern Europe appears in a 2010 literature survey by Berglund and Ekman who refer to the findings of the 2004 Handbook of Political Change in Eastern Europe and other sources when they define ten dividing lines in three broad categories related to periods of historical development (Handbook of European Societies, 100):

Historical

Contemporary

Transitional

|

Most of these refer to “demographic” clusters. The first four recapitulate the framework established by Lipset and Rokkan, and two others in the “contemporary” list extend and nuance this list to include a more inclusive variant on “workers versus owners” and the question of generational differences. Other entries on this list–those in italics–refer not to strictly demographic questions but to value or attitudinal questions about national identity and economic distribution which are related but not necessarily identical to the demographic categories. Still others–those underlined–point more toward conflicts in the institutional realm related to party organization and party institutions. In this list Lijphart’s more issue-based dimensions of foreign policy and postmaterialism are notably absent and the question of regime type appears only in partial form in the question of “apparatus versus forums.”

The nature of the list depends not only on the regional focus but the question at hand Kitschelt makes clear distinctions between the “fabric of sociodemographic traits and relations” on one hand and “preferences for political action” on the other, though he notes that both of these shape political choice (West European Politics, 2010, 661). His assessment of the “fabric of traits” does not specify particular demographic groups, but rather identifies a list of eleven potentially important characteristics:

|

Many of these are consistent with Lipset and Rokkan’s list as used by Berglund and Ekman, but Kitschelt’s framework here moves away from identifying specific groups toward identifying specific dynamics: religiosity becomes a kind of cultural preference, while economic questions of sector and class are disaggregated into a combination of status, occupation type, income, skill, and risk exposure.

Other scholars have engaged in a similar elaboration and transformation of attitudinal and value issues, not only separating these from assumed socio-demographic mooring but also seeking to split (and sometimes recombine) key elements.

Stoll’s work on Western Europe identifies “six theoretically interesting ideological conflicts” (West European Politics, 2010, 455)

|

But even though the differences between Western and “Eastern” Europe have diminished, Stoll’s list overlaps imperfectly with the lists employed by those who research the region. Of these, perhaps the most extensive is that of Whitefield and Rohrschneider, who identify eight primarily attitudinal conflicts in their expert survey (They also identify two variants of Lipset and Rokkan’s sociodemographic divisions–regional and urban-rural–but they do not use these in much of their subsequent analysis) (Comparative Political Studies, 2009, Appendix).

|

The question, as above, is whether the long list of value differences can be conveniently shortened. The expert surveys conducted by Hooghe and Marks begin with a simple two dimensional approach which looks separately at party positions on economic issues (role in the economy, taxes, regulation, spending and welfare state) and views on democratic freedoms and rights where they differentiate Green/Alternative/Liberal (GAL) attitudes (expanded personal freedoms, for example, access to abortion, active euthanasia, same-sex marriage, or greater democratic participation) from Traditional/ Authoritarian/ Nationalist (TAN) belief that government “should be a firm moral authority on social and cultural issues” ( While these two dimensions capture much that is in the Whitefield and Rohrschneider typology–particularly their two economy questions and their religiosity and “social rights” questions–they discard important information by conflating the elements of GAL/TAN, which in postcommunist Europe tend to remain separate. Postcommunist European authoritarianism has less to do with social regulation than it does in Western Europe and more to do with democratic institutions. Postcommunist European concern about nationalism and ethnic rights is relatively independent of questions about social rights. In this sense Kitschelt offers a slightly more suitable framework when he suggests a three-fold difference that adds a “group” dimension to the dimensions for economic and cultural (“grid”) regulation:

|

Even this triple division is limiting, however, since it folds questions about democracy into the “grid” category. Empirical work by Whitefield and Rohrschnieder find that democracy questions in Postcommunist Europe tend to correlate instead with national questions, but even here evidence suggests that the connection is contingent rather than necessary (Deegan-Krause 2007), and so it is best to hold democracy separate as a fourth relevant dimension.

Nor does any of this narrowing of dimensions address the role of the Communist era, which is not quite a demographic question–though it is closely related to the shift in individuals’ respective demographic positions between the Communist and postcommunist era–and not quite a purely attitudinal question. In this it may resemble to some extent the question of religiosity, which has both ascriptive and value elements. A brief look at the region suggests that on one hand it deserves to be treated as a distinct category, since in various settings “Communism” may mean anti-market, or anti-religion, or anti-national (or pro-national), but on the other hand it is arguable that the core of the dimension lies in whatever “Communism” and “anti-Communism” ally with rather than the question of Communism itself. This, however, is an empirical question that will simply need more study.

The question of Communism, in fact, calls attention to the underlying dynamics of the political conflict. “What are they fighting about?” may be the first question we ask when we approach a new polity (or try to figure out a polity that has become opaque to us over time) but we also need to know how the struggle occurs. We need to look at the depth of the conflict and the role of political institutions in shaping the struggle.

e

Works in progress: Thinking about cleavages, part I

In an effort to get some genuine writing done over the coming weeks, I am going to try to do some of that writing in a place and in a way that I enjoy, and so I plan to subject those who read this to a rather academic treatment of the question of “cleavage formation” and how it has taken place in Central and Eastern Europe. If this is not your cup of tea, then just skim right on by and come back later for more interesting stuff about Slovakia, the Czech Republic or complaints about local news anchors and the other sorts of things that occasionally appear on this blog. But for now, cleavages.

In an effort to get some genuine writing done over the coming weeks, I am going to try to do some of that writing in a place and in a way that I enjoy, and so I plan to subject those who read this to a rather academic treatment of the question of “cleavage formation” and how it has taken place in Central and Eastern Europe. If this is not your cup of tea, then just skim right on by and come back later for more interesting stuff about Slovakia, the Czech Republic or complaints about local news anchors and the other sorts of things that occasionally appear on this blog. But for now, cleavages.

The reason we study cleavages is that we want to understand conflict and to think about what is really at stake in the conflicts that dominate our polities. A question that can forms the basis of a cleavage is by definition something big, something that nearly all citizens care about enough to get out of bed and vote and that some care enough about to devote entire lives. It is also something enduring, something that, barring upheaval will be more or less the same in five years as it is today or as it was five years ago–and maybe fifty.

The search for basic, enduring conflicts has generated a broad literature about what should look for and how we would know it when we found it. In the process

Lipset and Rokkan created the literature with their … in 1967, but resisted a formal definition. Franklin summarizes the conditions for a cleavage as “When social groups recognize their political differences and vote for different parties because those parties are dedicated to defending the interests of particular groups”(Franklin, WEP, 2010)

Bartolini and Mair focused on each of these key elements in this definition in defining cleavage in terms of “a combination (overlap) of social-structural, ideological/normative, and behavioral/organizational divisions”(Kriesi, WEP, 2010). This tripartite operationalization has dominated subsequent cleavage research for the past two decades, though in the last decade it has seen a degree of challenge from those who seek to take away some elements and (or) add others.

Enyedi, in particular argues that the definition is overly restrictive in its insistence on the social-structural elements. He notes that Bartolini and Mair themselves acknowledge that the socio-demographic element of a cleavage may erode, and suggests that it may be possible to have a cleavage-like conflict between entrenched “sides” without all of the elements of Bartolini and Mair’s definition.