They don’t like it:

Case closed.

David Cerny’s exhibition catalog for “Entropa” is the only thing connected to the EU that has ever caused me to laugh out loud.

David Cerny’s exhibition catalog for “Entropa” is the only thing connected to the EU that has ever caused me to laugh out loud.

There is such remarkable cleverness here that I want to think about it out loud as well, but it is hard to do it without drifting into pretentious art criticism. So I will be try to brief.

At face value Cerny’s proposal for the artwork claims to want to force Europeans to confront the offensive stereotypes they have about those from other member states and calls for “self-reflection” and “critical thinking”? In other words, stereotypes are a joke.

But since the artwork seems to reinforce those stereotypes (ask Bulgarians about Turkish toilets), the artist claims (obliquely in the artwork’s catalog and explicitly in his apology) to want Europeans to ask whether they can tolerate the stereotypes that other Europeans have about their own respective countries, since the “capacity to perceive oneself as well as the outside world with a sense of irony are the hallmarks of European thinking.” In other words, maybe the real joke is that people don’t get the joke.

This will keep people talking for a week or so, and an artist whose goal was to get people thinking about their stereotypes and their reaction to being stereotyped could be marginally satisfied at having provoked a discussion (something that does not seem to have happened with any previous rotating-EU-presidency art installation). But while I don’t doubt that Cerny was aware of the possibility (and might even be happy with the result), I rather doubt that this was his goal. If I were to guess the main “artist’s question” that was going through his hard when he made this, I would guess this one:

Can I get away with this?

Amid all of the (not uninteresting) arguments about stereotypes, offense and irony obscure the most remarkable thing about this work: that it is there at all. He has succeeded in placing an artwork that many find deeply offensive into the middle of an EU building, and forcing Czech Republic to start its EU presidency with an apology. Mission accomplished.

Without trying to pursue analysis for which I am not trained, the main point for me is the weakness of official power. The point is that Cerny managed to get this past everybody, managed to invent artists from 26 other countries without anybody noticing, managed to insert the potentially offensive bits in full public view (the Bulgarian toilet is part of the catalog, couched in artspeak–” intentionally primitive and vulgar, faecally pubertal”) and–shielded by the debate (which he framed himself) over stereotype against “sense of humor” (and who wants to be accused of lacking one of those)–he may well manage to keep the thing hanging in Brussels for the next six months. That is some remarkable art.

I may see this only because this is what I saw in the two other Cerny pieces that I encountered in public in the last two decades. In spring of 1991 when I was teaching in Plzen I got a call from a friend to tell me to come to Prague and see “this amazing pink tank.”

I may see this only because this is what I saw in the two other Cerny pieces that I encountered in public in the last two decades. In spring of 1991 when I was teaching in Plzen I got a call from a friend to tell me to come to Prague and see “this amazing pink tank.”

In 2000, I was cutting through the Lucerna pasaz in Prague when I came upon Cerny’s “Horse” and nearly fell down laughing. Again, the amazing thing was that he had punctured–actually obliterated–a core national myth within a few hundred feet of the real statue (see http://www.ce-review.org/99/19/pinkava19.html and Cerny’s own webpage: http://www.davidcerny.cz/EN/vaclav.html, especially his commentary).

To overthink this for a moment (because the real point is that it is really funny), I think Cerny’s art is funny to me because it says that the powers that be are not as powerful as they think. I’m sold on the theory (thanks to Mark Lutz) that one of the reasons we laugh is that we are relieved to find out things we were afraid of are actually not that fearsome. If Cerny could manage to paint a tank pink or mock a national hero, then maybe there were a lot of things that the rest of us could get away with. So in this sense Cerny’s exhibits follow in the tradition of resistance through humor from the Good Soldier Svejk to the Theater of Jara Cimrman and the staged actions of the Committee for a Merrier Present (Spolecnost za veselejsi soucasnost), except that Cerny’s work came after the fall of Communism. (Havel’s Power of the Powerless suggests something like this, suggests that western governments have their own kind of anonymous bureaucracy; Terry Gilliam’s Brazil makes the same point). The fact that such guerilla art was still funny said something about our continued fear of the powers that be–from the continued influence of Russia (and those too afraid to fight it) connected to the Pink Tank, to the turn toward national reverence questioned by “Horse.” Now the target is the European Union and for better or worse, the joke is still funny.

Three final last things that I can’t resist mentioning:

First, Cerny’s “apology” is itself a work of art, a beautifully designed document designed to admit just enough to keep the conversation going. It is delightfully multilayered including the final sentence:”the piece thus also lampoons the socially activist art that balances on the verge between would-be controversial attacks on national character and undisturbing decoration of an official space.” It is yet another beautiful irony that the presumed goal of the apology–keeping the artwork hanging–makes it yet another example of the kind of art that Entropa is supposed to be criticizing.

Second, it is amusing to me that a piece of art allegedly about national stereotypes plays directly to my own stereotypes. When I think about what I love most about Czechs, I think about their penchant for subversive humor. This is itself a stereotype, I think. There’s no reason that Czechs are any more likely to do this kind of thing than those of any other national group. At the same time Czechs do seem more likely to embrace this kind of humor as part of their national heritage than do other European countries. In that sense, Cerny’s Entropa itself is just as much an example of stereotype as the alleged pieces in his artwork.

Finally, Cerny’s exhibition catalog really repays careful reading, ranging from parody of artspeak to gems worthy of Douglas Adams.

There are also lovely gems snuck into the artists’ biographies including:

I’ve used up another 15 seconds of fame, this time in the Monday, September 29, Vitebski Kurier:

Translation:

Did expectations come true?..

Our attempt to have a conversation with one of the long-time observers of OSCE, coordinator Gary Ouellet from Canada were not successful. He providently refused by phone or other means to make any evaluations or comments on organization or process of the elections. His interpreter politely advised us to address all the questions to the headquarters of OSCE in Minsk. Nor did we manage to meet any other observers at polling stations to ask for their impressions. Nevertheless we were lucky to have a brief conversation with short-time observers Astrid Ganterer and Kevin Deegan-Krause (see photo) before the meeting of the District Election Commission of Vitebsk’s DEC #19 in the regional state administration building. It is their first time in Belarus, and they saw some parts of Vitebsk and Minsk. The representatives of OSCE mission persistently avoided all the questions connected to the elections. They kept silence, not revealing if their expectations came true or not. One could see either exhaustion or disappointment in their faces. Still, our foreign guests promised to answer all questions at the press-conference in Minsk…” (Thanks to our translator and several friends for clarifying the Russian).

Actually I am not allowed to clarify what emotion was on my face that day, but if it was reflective of the faces of those who reported for the OSCE in Minsk that day, then “disappointment” would seem to be an appropriate choice (see http://www.osce.org/minsk/).

P.S. Search the picture above closely for the Hidden Lukashenka. If you enjoy that, you might want to try this Hidden Picture.

P.P.S. More election observation pictures (taken by others) online at:

Amid constant news of contraction and decline this week, there is (slightly old) news of yet another small but significant expansion: machine translation to and from Slovak. Machine translation is old news these days (though it is no less remarkable for our acceptance of it) and is no panacea (it is still bad enough that without a basic understanding of the language it is easy to be deeply confused or seriously misled), but it is nice to see Slovak make the list of Google Translate languages.

For this blog it makes little difference–the population of those who are interested in what goes on here but cannot read English is infinitesimal–but it is nice to be able to make the gesture and all subsequent posts here will include a link like the one below allowing automatic translation.

I hope in future to go one step further and install a plugin that makes that process even easier.

Ceremonial president of former Czechoslovak republic seeks same. Must be medium height and and medium build, with grey hair cut short, and not unstylish glasses. Trimmed grey moustache and willingness to support the current governing coalition a plus.

It has taken 15 years, many elections and several hairstylists, but Slovakia and the Czech Republic have finally begun the process of re-convergence, beginning from the top down. Are two countries really separate if you cannot tell them apart anymore?

(or why Dr. Sean hits the nail on the head)

Kudos to Sean Hanley for his recent post, Do Slovak and Czech Christian Democrats have a prayer? Dr. Hanley, whose blog (Dr. Sean’s Diary, http://drseansdiary.blogspot.com/) has long been my model for public, academc discourse on postcommunist Europe, yet again calls attention to precisely the questions I am trying to think about. Not only does he do an an excellent job of covering the dilemmas of the Christian Democrats in the Czech Republic, a realm that nobody knows better than he, but he also offers provocative thoughts about intra-party struggles, coalitions and election results in Slovakia:

And generational renewal? Commentators and politicians in CEE are always harping on about this, but it’s hard to see quite newer or younger will necessarily mean better. Such comments are, usually a disguised call for in political renewal or cleaner, better, more liberal government – amen to that, but even though there is no primaries system there is ample scope for new parties to emerge or young technocrats to parachute themselves into organizationally weak, elite-led parties. The Slovak experience suggests that many voters don’t want renewal of this kind, but stability. Is the Slovak Barack Obama actually Robert Fico?

Though the comparison may not be desirable to some partisans of Obama or of Fico, there are important similarities that must not be overlooked. I continue to wrestle with the concept of “populism” since in its common usage it is both vague and highly normative:

Populism

But if populism does mean anything–and I think it does mean something despite all of the accretions over time–it is a sense that politics is broken. It is a feeling (though not quite an ideology) that those in public office–both those in power and those in opposition–are the cause of the problem. By this standard, of course, nearly every American politician is a populist, but if you compare them to many of their European counterparts, that is actually a fairly accurate characterization. While I have not done the spadework to explain why, I suspect that America’s relative exceptionalism in this regard has a lot to do with its presidential system, the dominant role of media, the relative absence of party organization. Many European countries are moving in this direction, however and postcommunist Europe appears to be in the vanguard. In this sense, both Fico and Obama have become preferred choice for those voters who are tired of “politics as usual” and who seek something different. Those are different kinds of voters compared to their overall electorates, but that is a different story.

Party renewal

There is a lot more to say about the question of populism, and I hope to do so over the coming months. In the meantime, however, I want to point out one very important difference between Obama and Fico and one that goes to the heart of Prof. Hanley’s question: Barack Obama is still a member of the Democratic Party and it is hard to imagine him leaving the party if he loses the nomination; Robert Fico, on the other hand, left his original party and formed a new one.

Fico is not alone in this. Indeed questions of internal-party change and party defection are central to the course of Slovakia’s politics and to the politics of many countries in the region. Dr. Hanley is right to point out that the question is not whether parties can achieve generational change; renewal can easily occur within a single generational cohort. Rather, the question is whether renewal can occur within a single party. Two phenomena mark Slovakia’s political party system: the relative infrequency of institutionalized leadership change and the relative frequency of party splits and splintering.

Loyalty: The Rarity of Party Leadership Change

Parties in Slovakia rarely change leaders and they almost never undergo institutionalized leadership transitions. Among Slovakia’s current parliamentary parties. As the table below shows, the average tenure of the chairmen of Slovakia’s current parliamentary parties is between 8 and 9 years (depending on the method of calculation), and this represents an average of 67%-71% of their parties’ respective lifespans.

| Party | Founding Date | Number of leaders since founding | Current leader | Date assumed leadership | Duration of leadership | Length of leadership as % of length of party existence |

| Party of the Hungarian Coalition (MKP/SMK) | 1990 | 2* | Pal Csaky | 2007 | 1 year | 6% |

| Christian Democratic Movement (KDH) | 1990 | 2 | Pavol Hrusovsky | 2000 | 7 years | 41% |

| Slovak National Party (SNS) | 1990 | 5 | Jan Slota | 1994 | 9 years/13 years** | 53%/76%** |

| Movement for a Democratic Slovakia (HZDS) | 1991 | 1 | Vladimir Meciar | 1991 | 16 years | 100% |

| Smer | 1999 | 1 | Robert Fico | 1999 | 8 years | 100% |

| Slovak Democratic and Christian Union (SDKU) | 2000 | 1 | Mikulas Dzurinda | 2000 | 7 years/9 years*** | 100% |

| Mean scores | 1993 | 2 | – | 1999 | 8-9 | 67%-71% |

| http://www.terra.es/personal2/monolith/slovakia.htm* Party formed from merger of Hungarian Christian Democratic Party (MKDM) and Coexistence in 1998 **Jan Slota rejected his removal in 1999 and formed the rival “Real” Slovak National Party (PSNS) during his period out of leadership in SNS. ***Mikulas Dzurinda led the Slovak Democratic Coalition before leading the SDKU |

||||||

Indeed three parties, Smer, SDKU-DS and HZDS (which together hold almost 2/3 of the deputies in parliament), have had the same leader for their entire existence. The same is true in practice for several significant parties that are currently no longer represented in parliament (ZRS, ANO). Other parties have undergone leadership transition by default as founding party leaders became president (SOP, HZD) or withdrew from politics (KDH). Only a handful of parties have enjoyed (though for them, “enjoy” may not have been the right word) contested leadership struggles that actually changed the course of party leadership. The Party of the Hungarian Coalition (MKP/SMK) resolved internal leadership questions when it formed from its component parties in 1998 and underwent a leadership shift again in 2007. The Party of the Democratic Left (SDL) underwent major leadership transitions in 1996 and 2001. The Slovak National Party (SNS) is the closest to demonstrating regular leadership change (1990, 1992, 1994, 1999, 2003) but change in party leadership after 1992 has been fraught with difficulty and appears for the moment, to be at an end.

Exit: The Frequency of Party Splintering

New party leaders in Slovakia are more likely to be leaders of new parties than new leaders of old parties. Whereas the six parties listed above have collectively only experienced seven or eight leadership changes (depending on calcuations), they have collectively experienced at least ten significant splits and splinters of parliamentary deputies or prominent party leaders. Secession is far more common than succession. It is difficult to find struggles between party incumbents and party insurgents that have left a party intact: SDL in 1994 (to the extent that Peter Weiss’s withdrawal was not entirely voluntary), SNS in 1992 and 2003, and MKP/SMK in 2007. Far more common is struggle followed by departure of the loser to form a new party: SNS in 1994 and 1999, SDL in 1999 and 2001 (and, to the extent there was a real struggle, with the departure of Luptak in 1994), KDH in 1991, 2000 (related to the dissolution of the SDK coalition) and 2007 (just last week, in fact), SDKU in 2003 and the seemingly annual HZDS splinters in 1993, 1994, 2002, 2003, (and in miniature formjust recently). In fact the only parties in which party struggles have not led to departure are the Hungarian Coalition (which is limited by the inability of Slovakia’s 11% Hungarian population to support two parties that can overcome the 5% threshold), new parties that have died before a split could occur (SOP, ANO, ZRS) and a variety of smaller parties that never by themselves passed the 5% threshold (indeed Slovakia’s small parties such as the show more robust leadership rotation and a greater ability to survive leadership struggles, perhaps because they are too small to lose any members without disappearing entirely. See The People’s Front of Judea).

Why do Slovakia’s parties splinter so easily? This is a complicated and fascinating question that I am currently working on in greater detail. Institutional barriers to entry for new parties are low, but not much lower than in other parliamentary/proportional-representation systems in Europe. A stronger answer may lie in perceptions of cost and benefit. The perception of departing may be relatively low in Slovakia because certain splinters have demonstrated electoral success (DU and ZRS in 1994, Smer in 2002) and other parties have demonstrated an ability to go from nowhere to election in a matter of months (SOP, ANO). I do not, however, have the evidence to say whether these cost perceptions are lower than in countries with fewer splinters. The second part of the answer may lie in the perceived costs of remaining within a party. This in turn relates to the perceived absence of voice.

Voice: It’s (Not) My Party

My initial observations suggest that Slovakia’s centralized party organizations make it difficult for dissenters to remain. When parties remain in the hands of their founders, as in the case of Smer, HZDS and SDKU, or become tightly bound up with a successive leader, as in the recent case of SNS, those who wish to change the party may have no choice but to go elsewhere, particularly if they openly challenge the leadership. The strength of this conclusion is mitigated somewhat by the fact that even the more collegial SDL and KDH have produced a significant share of Slovakia’s splinters, and even some in the vulnerable Hungarian Coalition appear to have considered departure. Nevertheless, it is hard for me to believe that structures more conducive to internal democracies, structures that took party control out of the hands of the founder, could produce more renewal and fewer departures. I have not read Hirschmann in a long time, but it seems like introducing genuine opportunities for voice could provide an alternative both to frustrated loyalty and to destabilizing departure.

In this regard, recent discussions within the current opposition are a very positive sign. It would appear that the current infighting within parties that are already at a low point in their political fortunes will only make matters worse–and in the short run this is true–but in the long run, the kinds of discussions emerging among second-rank leaders in SDKU, KDH and MKP/SMK are potentially conducive to long-term survival, party renewal (much needed) and electoral success. By this standards the current governing parties have a short-term advantage in internal cohesion, but are at greater risk of long-term difficulties because they include some of the most centralized parties that Slovakia has ever seen. In terms of broader patterns, the news is good because it is potentially quite normal: parties in power put themselves at risk by failing to adapt; parties out of power learn how to renew themselves and eventually rise to the challenge. If Slovakia’s current opposition can manage to find mechanisms for voice and reform from within, Slovakia could experience the novelty (for Slovakia, at least) of an opposition-coalition struggle that is not also the struggle between old parties and new.

I used to wonder at blogs that dwelt on the minutiae of servers and hosts. No more. If you are reading this, then this blog (like Slovakia) has made a successful triple transition: a new platform (WordPress is proving worthy of the switch), a new host (many thanks to Joe Oravec at Wayne State for his remarkably able and generous help), and a new domain registrar (absolutely no thanks to Networksolutions for one of the worst customer service experiences I could imagine. It is one thing not to respond to queries. It is another, and far worse, to respond–as they did twice–with automated messages which suggested–incorrectly, of course–that the problem could be solved by purchasing additional Networksolutions products.

To test this new, I will post the poll average data from the last 1/3 of 2007 in a separate post. Average data from the current month may be available as soon as today.

Of course there may still be some glitches and so I would appreciate any comments here about anything here that does not work or just looks bad.

This week’s discovery presents the perfect opportunity to express my ongoing gratitude to my dissertation adviser, A. James McAdams.

Among the many other ways in which he has shaped my work, Jim sent me off to my first year of fieldwork in 1993 with one of the most productive tools in my research I have ever encountered: a question. “When you get home at night,” he suggested, “write just a few sentences on the question, “What surprised me today.”

In other words, what did I encounter that I did not expect? What looked different than I would have guessed? What did not fit the model? I have not done this as regularly as I would have liked, but it is a question that has consistently called me to look for the holes in my models, the limits of my understanding, the places where I see what I want to see and disregard the rest. That’s where the interesting stories emerge. And if I cannot think of something that answers the question, then I know I am doing something wrong, because I am blinded by my almost assuredly limited, if not utterly wrong, presuppositions.

I was delighted this week, therefore, to encounter something that made my job all-too-easy. While walking through the Slovak town of Samorin I passed an attractive park with a stone walk and a series of stone plinths, on each of which was a bronze bas relief of a human face.

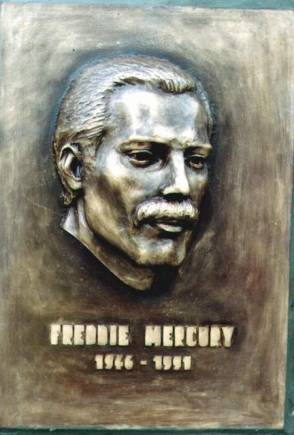

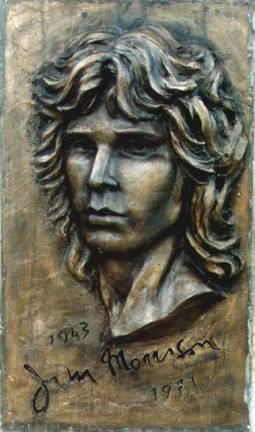

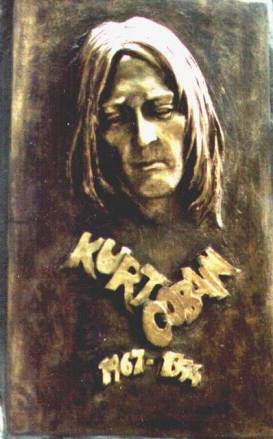

This is the kind of thing I am always curious about. What I expected was plaques of obscure (to me) local figures from the communist era (national-level figures such as Husak or Jakes would probably not have survived past 1990), or perhaps, given the ethnic composition of the region, even figures from 19th century Hungarian history (with signs that these replaced had earlier plaques of Husak and Jakes). What I did not expect were these figures:

Freddie Mercury, John Lennon, Jim Morrison and Curt Cobain. Not pictured here–because they are unfortunately not yet on the park’s website–are additional plinths dedicated to Jimi Hendrix and Bon Scott. The website explains that the plinths and plaques were erected by a civic group called “Immortal” founded in 1992 to “provide financial aid to anti AIDS and drug publications, moreover we help financially and provide concert opportunities to the beginner local and regional bands.” The Slovak Spectator has a bit more information here.

So having found my surprise, I must wonder what to make of it. As a student of politics, I am paradoxically delighted to see an emphasis on the non-political. While more than a few fights have erupted over musical taste (see below), the choice of rock stars here does not have same potentially divisive character as a set of political representations, and so it is good to see. (It is reminiscent of a comment by a Czech friend who pointed out how much simpler life would had been if local mayors had insisted on streets named after trees and flowers instead of political figures. Between 1918 and 1992 the name of street of my institute in Plzen changed from Franz Josef, to Woodrow Wilson, to Hermann Goering, to Victory, to Stalin, to Moscow, to Svoboda, back to Moscow, and finally to America).

And yet, politics remains an issue, particularly when it involves rival ethnic groups. The same group that built the music park–Immortal–also lists among its activities the creation of a statue of (Hungarian) King Istvan. There is no lack of ethnic symbolism in such a choice and no absence of politics. The issue of ethnicity does not go away, even though members of ethnic communities may sometimes actively focus on uniting rather than dividing. Through the work of Immortal in Samorin, “Imagine” meets “We Are The Champions” in more ways than one.

Finally, as a postscript, there is the question of music, about which I have no expertise but lots of opinions. The recent elevation of Bon Scott of AC/DC raises questions about the current direction of the foundation. Its members does not appear to have rejected candidates on the basis of lifestyle or cause of death. The only common denominators appear to be “rock star” and “died young” and so it is rather a shock that Scott precedes Bob Marley and Keith Moon and a variety of others. Unfortunately the current trend points instead toward Jeff Pocaro of Toto and Steve Clark of Def Leppard. Fortunately this may lead at long last to memorials for the deceased drummers of Spinal Tap (if they can find enough room in the park).