In a few hours (22:00 CET, 4pm ET) the papers and TV stations will fall all over themselves to present early results based on exit polls (unless they ignored the lesson that STV learned the hard way in 2006: even the most elaborate large-sample pre-election survey is not the same as an exit poll). About an hour later, results will begin to trickle in and then turn into a torrent. Both of these allow just enough data to make a prediction about the final result. Those with any common sense will go to a movie or find something else to do until about 0:30 CET/6:30 PM ET when there may be enough data to make a final call (though in an election as close as this one, that may not be enough time), but there is probably not anybody that sensible still reading this blog. So if you want to make a guess about the final from the exit polls or from the early results, here is what to do:

In a few hours (22:00 CET, 4pm ET) the papers and TV stations will fall all over themselves to present early results based on exit polls (unless they ignored the lesson that STV learned the hard way in 2006: even the most elaborate large-sample pre-election survey is not the same as an exit poll). About an hour later, results will begin to trickle in and then turn into a torrent. Both of these allow just enough data to make a prediction about the final result. Those with any common sense will go to a movie or find something else to do until about 0:30 CET/6:30 PM ET when there may be enough data to make a final call (though in an election as close as this one, that may not be enough time), but there is probably not anybody that sensible still reading this blog. So if you want to make a guess about the final from the exit polls or from the early results, here is what to do:

How to guess from the exit polls:

Don’t, especially for close races (like whether Most-Hid and HZDS are above the threshold). Exit polls are better than other kinds of polls but they are far from perfect. Below you can find two charts with exit poll results and actual results, one for Slovakia in 2006 and one for the Czech Republic just two weeks ago in May 2010. They are remarkably similar in their overall results: the average difference between exit polls and actual results for the eight top parties in each is about 0.7 or 0.8 and as high as 2.0 even for medium-sized parties. This translates into differences up or down of as much as 20%, especially (but not exclusively) for the smaller parties. If we could assume that the 2010 difference would resemble that of 2010, then I think we could make a better prediction from exit polls, but except for SNS (whose voters might not be able to quite admit their choice to a bunch of young exit pollsters), I am not sure how this year’s exit polls will differ from results. Of course if HZDS scores 7.2% or SMK-MKP scores 3% we can be fairly sure of those parties final position vis a vis the exit polls, but I don’t expect this.

| Country | Party | Exit Poll | Results | Exit Poll Raw Error | Exit Poll Percentage Error |

| Slovakia 2006 | Smer | 27.2 | 29.1 | -1.9 | -7% |

| SDKU | 19 | 18.4 | +0.6 | +4% | |

| SNS | 9.6 | 11.7 | -2.1 | -18% | |

| HZDS | 8.6 | 8.8 | -0.2 | -2% | |

| SMK | 11.8 | 11.7 | +0.1 | +1% | |

| KDH | 8.6 | 8.3 | +0.3 | +3% | |

| KSS | 4.7 | 3.9 | +0.8 | +21% | |

| SF | 3.8 | 3.5 | +0.3 | +10% | |

| Average (absolute value) | 0.8 | 8% | |||

| Country | Party | Exit Poll | Results | Exit Poll Raw Error | Exit Poll Percentage Error |

| Czech Republic 2010 | Average (absolute value) | 0.8 | 8% | ||

| CSSD | 19.5 | 22.08 | -2.6 | -12% | |

| ODS | 20 | 20.22 | -0.2 | -1% | |

| TOP09 | 17.5 | 16.7 | +0.8 | +5% | |

| KSCM | 10.5 | 11.27 | -0.8 | -7% | |

| VV | 11 | 10.88 | +0.1 | +1% | |

| KDU | 4.5 | 4.39 | +0.1 | +3% | |

| SZ | 3 | 2.44 | +0.6 | +23% | |

| Suverenita | 3 | 3.67 | -0.7 | -18% | |

| Average (absolute value) | 0.7 | 9% | |||

So take a sip of the exit polls, roll them around your mouth, and spit them back and wait for the full glass.

How to guess from early results

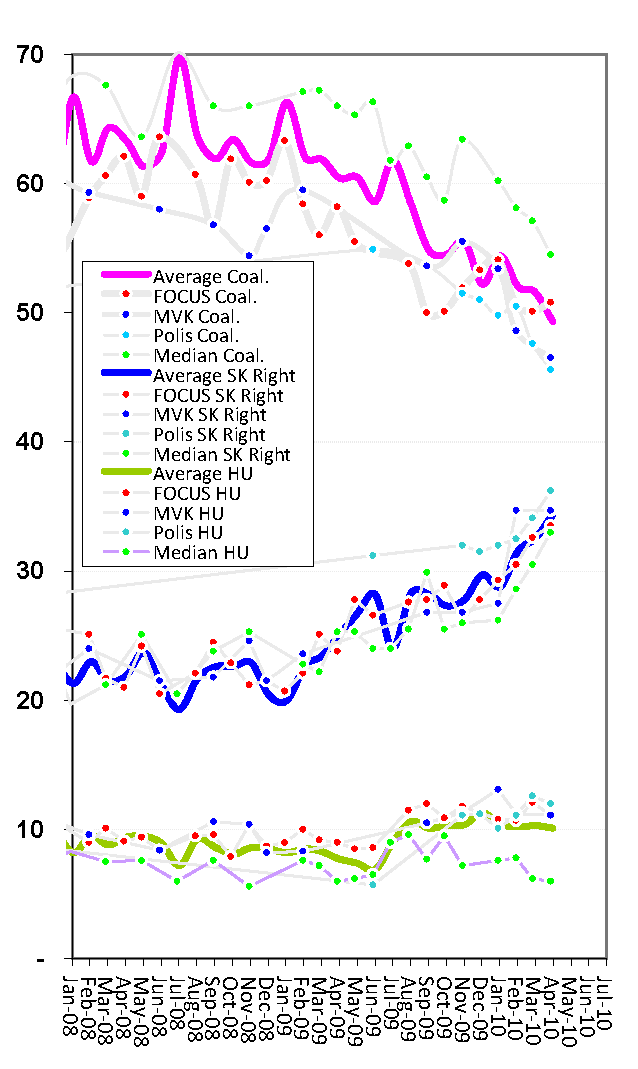

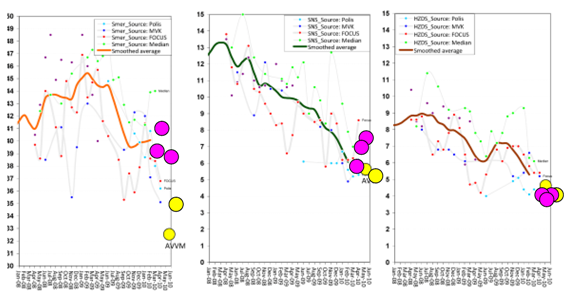

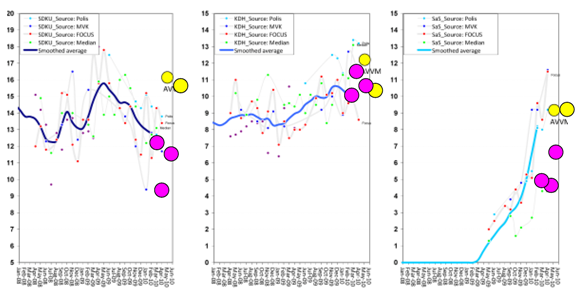

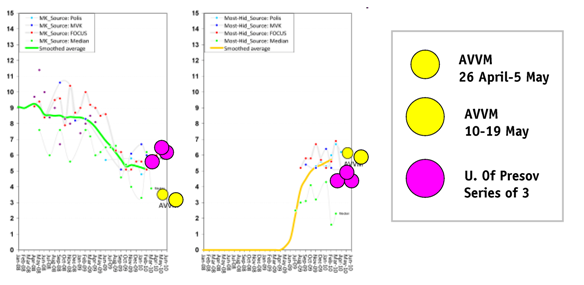

I was surprised not to see this done in 2006 (or in the Czech Republic two weeks ago), but maybe I missed it. It should be possible to use the patterns of voting returns from 2006 to help make predictions from early results. In my 2006 live-blogging of the election I actually took snapshots of the results as they came back over time, and I hope to use these tonight to make a better guess. Because the speed of election returns has to do with the size and rurality of precincts, some parties early returns were higher or lower than the final by a significant amount, as the graph from 2006 shows:

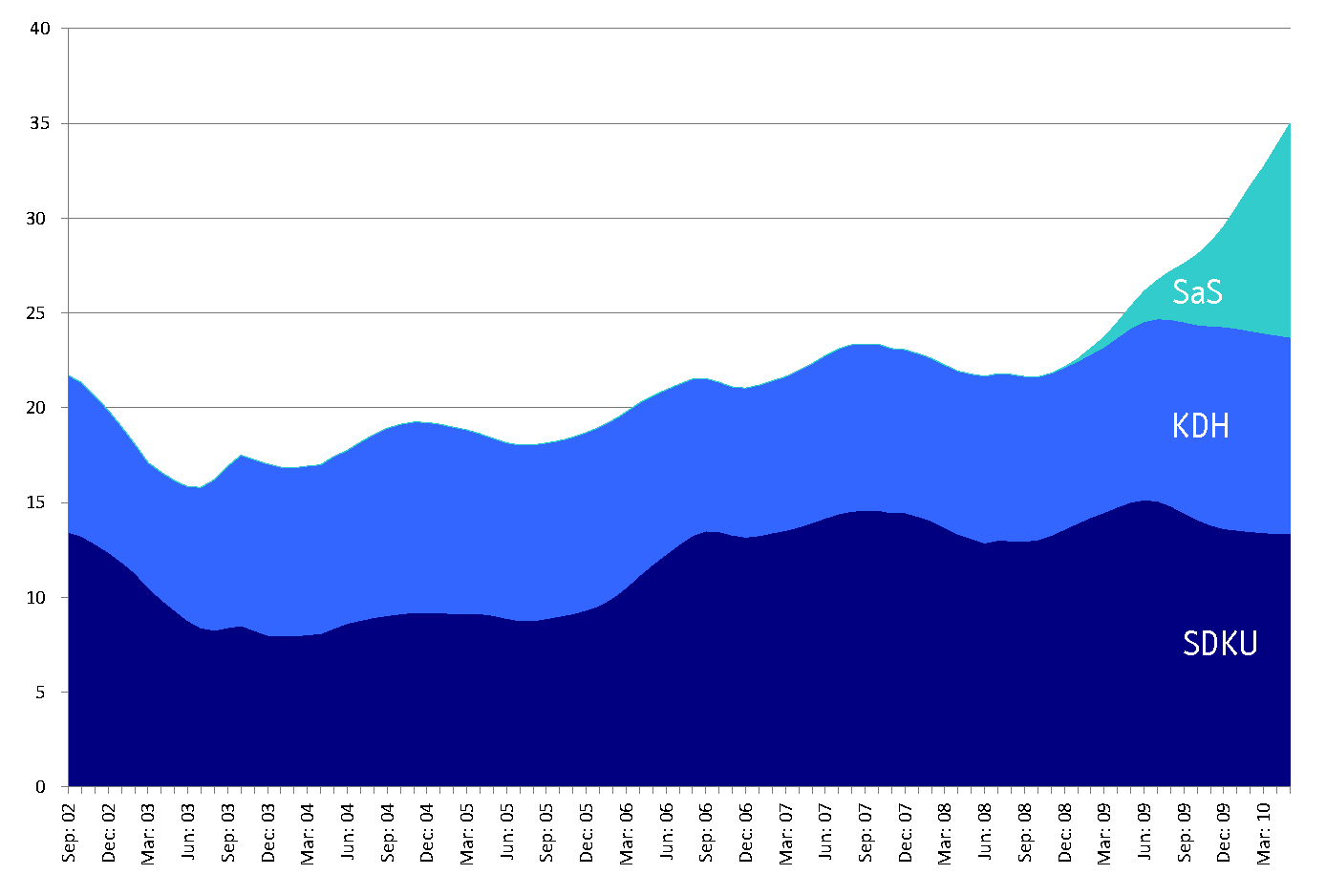

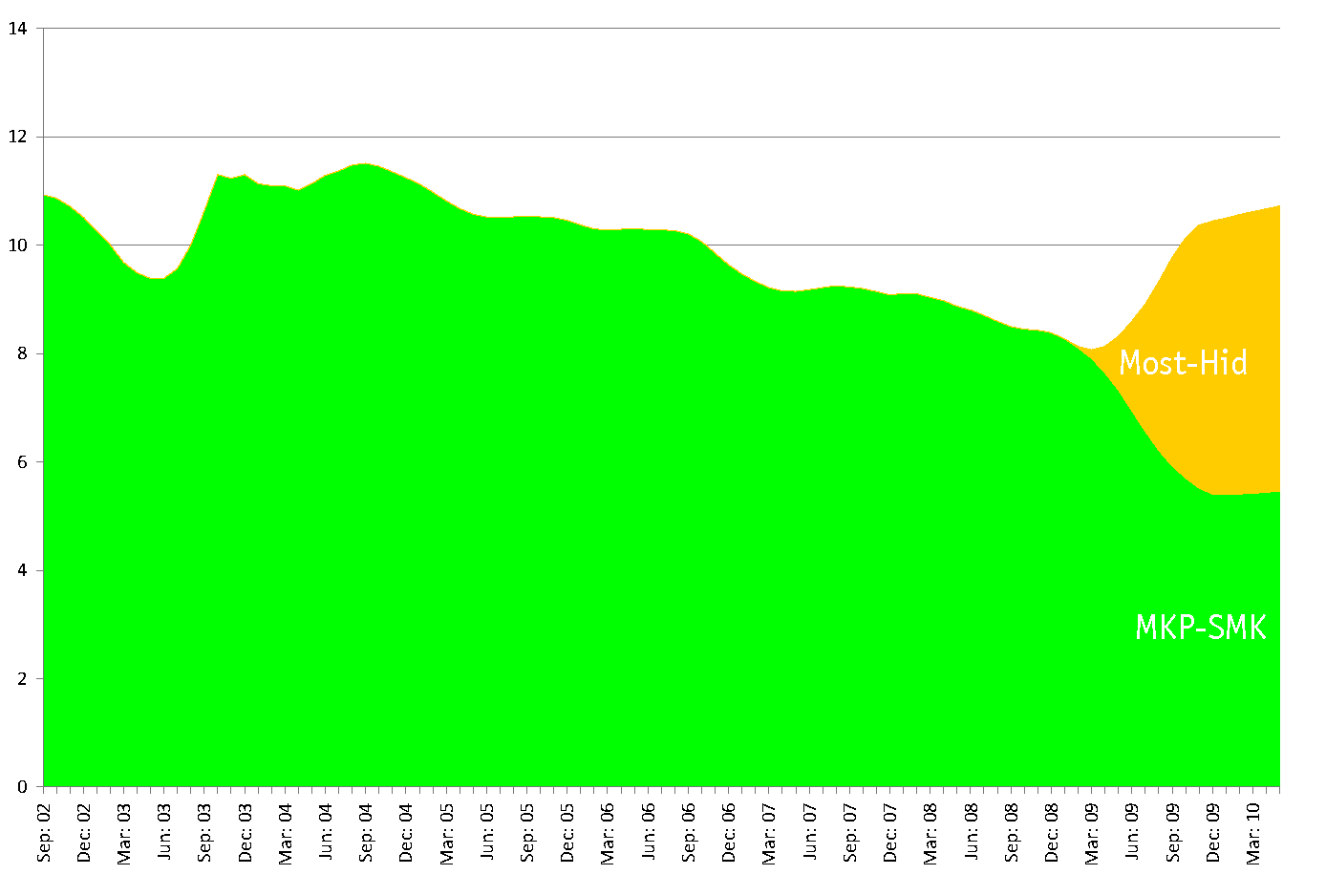

Parties with more rural electorates–KDH in light blue, HZDS in brown–tended to decline as the larger urban precincts began to report later in the process (Smer declined as well, though its urban-rural share was about average). More urban parties–SDKU and SF in particular–tended to increase. SNS and MKP-SMK, with concentrations in middle-sized towns did not change much (though this year things will be different at least for MKP-SMK which has lost much of its urban electorate to Most-Hid and should more closely resemble KDH and HZDS, with a declining trendline).

Because parties characteristics with regard to such factors changes quite slowly, this should actually provide a fairly stable source of data that would allow us to use the 2006 data to adjust the 2010 early returns (though I will also be testing the trends from 2010 against those of 2006 as they happen to see if they truly are consistent.) In any case, if 2006 serves as a good guide, here is a matrix to calculate the “actual result.” Search for party and the number of precincts returned at any given time and multiply the result of your party by the percentage listed.

| Party | Adjustment factor: Multiply party score by percentage below to get better predictions of actual results | ||||||

| Number of precincts reporting | |||||||

| 1000 | 2000 | 3000 | 4000 | 5000 | 5800 | 5900 | |

| Smer | 92% | 95% | 96% | 97% | 98% | 100% | 100% |

| SDKU | 123% | 109% | 105% | 105% | 104% | 101% | 100% |

| SNS | 100% | 100% | 100% | 101% | 101% | 100% | 100% |

| MKP | 109% | 109% | 108% | 100% | 96% | 99% | 100% |

| HZDS | 92% | 99% | 101% | 101% | 102% | 101% | 100% |

| KDH | 94% | 96% | 96% | 98% | 101% | 100% | 100% |

| KSS | 89% | 94% | 97% | 98% | 99% | 100% | 100% |

| SF | 118% | 105% | 102% | 103% | 102% | 100% | 100% |

I will try to do this on the blog, but feel free to try it at home. It would not surprise me if the Slovak press has something like this in store (though I have occasionally criticized them for their use of polls, Slovakia’s journalists have been fairly good at adopting new methods if they will give them a leg up on the competition.

I make no promises for this model any more than for the exit poll adjustment, but those who have not done the sensible thing and simply ignored the whole thing until final results are in will probably appreciate the entertainment value.

There is an old saying that “figures don’t lie, but liars do figure” (which I’m sure has some equivalent in almost every language) and there is a wonderful book written in 1954 provocatively entitled “

There is an old saying that “figures don’t lie, but liars do figure” (which I’m sure has some equivalent in almost every language) and there is a wonderful book written in 1954 provocatively entitled “

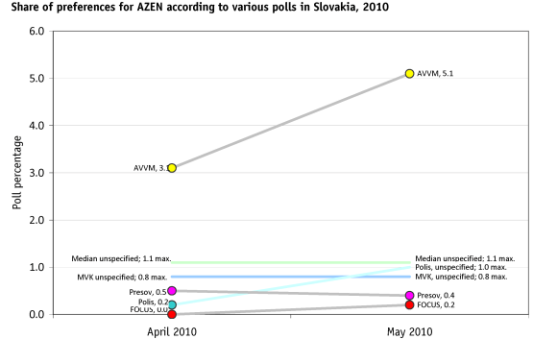

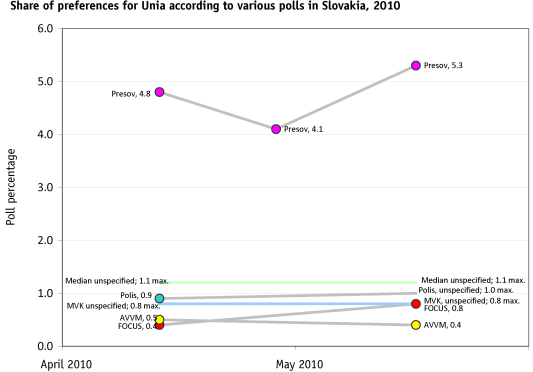

If AVVM hasn’t figured out some way to control for this then either a) its polls do not deserved to be published anywhere or b) I will be able to win a significant share of Slovakia’s vote simply by registering a new party under the name “Aardvark Alliance”

If AVVM hasn’t figured out some way to control for this then either a) its polls do not deserved to be published anywhere or b) I will be able to win a significant share of Slovakia’s vote simply by registering a new party under the name “Aardvark Alliance”

The area around the station is full of billboards. Amongst those of the centre-right Slovak Democratic and Christian Union – Democratic Party (SDKU-DS) and the Christian Democratic Movement (KDH) are several of the Slovak National Party (SNS). SNS’s pitch to voters is to pluck at xenophobic and nationalist heart strings. Whilst one of the billboards declares the party’s desire to ensure ‘that our borders remain our borders’ (a clear criticism of the big neighbour to the south), another wants to ensure ‘we don’t feed those who don’t want to work’ underneath a picture of a large, heavily tattooed Roma. Given Presov’s large Roma minority, this is a poster which sadly might be quite effective.

The area around the station is full of billboards. Amongst those of the centre-right Slovak Democratic and Christian Union – Democratic Party (SDKU-DS) and the Christian Democratic Movement (KDH) are several of the Slovak National Party (SNS). SNS’s pitch to voters is to pluck at xenophobic and nationalist heart strings. Whilst one of the billboards declares the party’s desire to ensure ‘that our borders remain our borders’ (a clear criticism of the big neighbour to the south), another wants to ensure ‘we don’t feed those who don’t want to work’ underneath a picture of a large, heavily tattooed Roma. Given Presov’s large Roma minority, this is a poster which sadly might be quite effective.

By the time Iveta Radicova speaks it is already over two and a half hours since the event was supposed to start and the rain has been almost unceasing. The water has seeped through the fabric of my shoes and has made my feet all wet. After a few words from the woman who could be prime minister in a few weeks time, all of the party candidates assemble on stage for the grand finale> a rousing rendition of the campaign song ‘Modra je dobra’ (‘Blue is Good’). It’s a great song, originally recorded by the Czech band ‘Zluty pes’, but after so long standing in the rain with soaking socks all I think about is that maybe ‘Modra je dobra, ale mokra nie je’.

By the time Iveta Radicova speaks it is already over two and a half hours since the event was supposed to start and the rain has been almost unceasing. The water has seeped through the fabric of my shoes and has made my feet all wet. After a few words from the woman who could be prime minister in a few weeks time, all of the party candidates assemble on stage for the grand finale> a rousing rendition of the campaign song ‘Modra je dobra’ (‘Blue is Good’). It’s a great song, originally recorded by the Czech band ‘Zluty pes’, but after so long standing in the rain with soaking socks all I think about is that maybe ‘Modra je dobra, ale mokra nie je’.

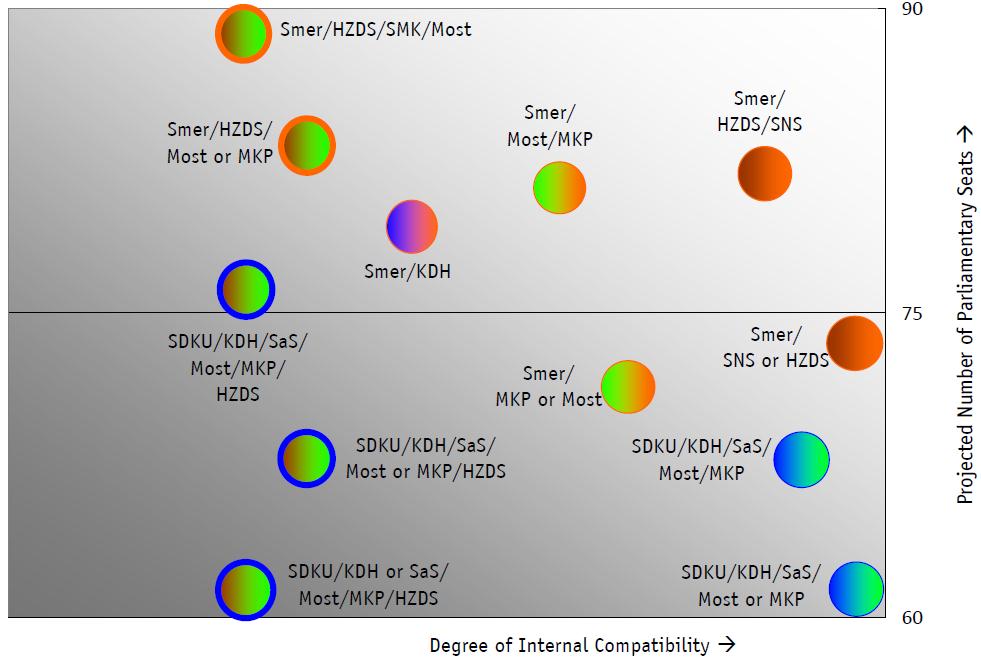

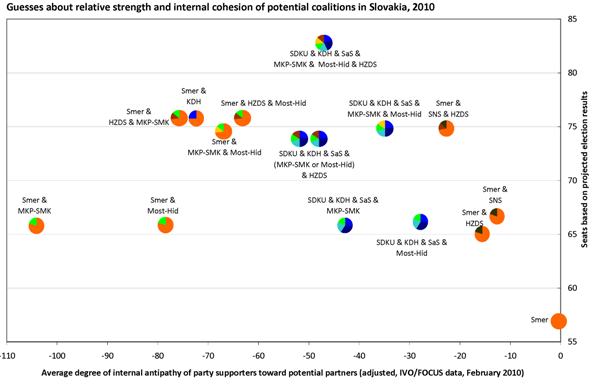

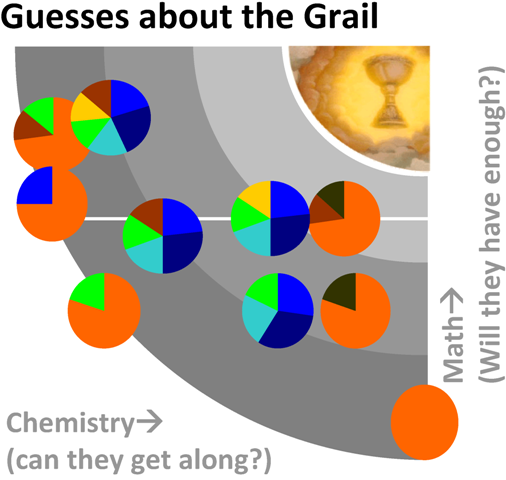

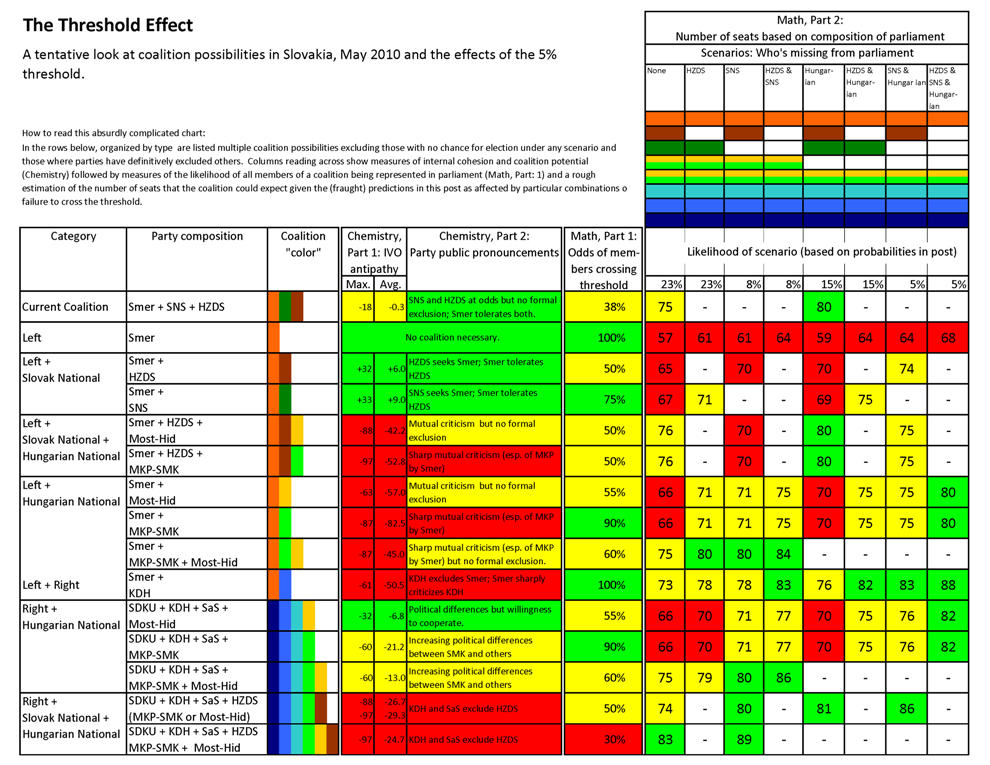

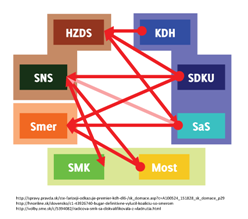

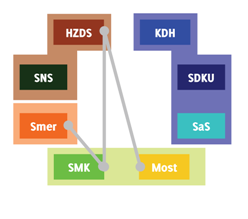

And in any case there is almost no circumstance in which any of these would help create a coalition except, perhaps, the unlikely Smer-SMK-HZDS “coalition from hell” (or as Ben Stanley puts it better than I ever could, “Sounds like a job for the Large Hadron Collider.” So this evidence points toward either a continuation of the current coalition (hard to manage if one of the two Slovak national parties drops out) or its replacement by the opposition (hard to manage if one of the Hungarian national parties drops out)…

And in any case there is almost no circumstance in which any of these would help create a coalition except, perhaps, the unlikely Smer-SMK-HZDS “coalition from hell” (or as Ben Stanley puts it better than I ever could, “Sounds like a job for the Large Hadron Collider.” So this evidence points toward either a continuation of the current coalition (hard to manage if one of the two Slovak national parties drops out) or its replacement by the opposition (hard to manage if one of the Hungarian national parties drops out)…