Those of you who are not deeply interested in how Slovaks vote (i.e. nearly everybody) can tune out. Those of you who are interested, I understand your pain, and you can now find all of this blog’s monthly public opinion graphs available in one place by clicking the “Dashboard” link on the top of every page. If it doesn’t work for you, leave a comment that lets me know what browser you are using (I.E. versions seem to have particular problems) and I’ll be glad to send you an updated PDF. I’ll still be inserting graphs in posts, but this is one way to get the data up quickly without spending time on analysis, and maybe that will prevent me from being so late in posting the data.

Those of you who are not deeply interested in how Slovaks vote (i.e. nearly everybody) can tune out. Those of you who are interested, I understand your pain, and you can now find all of this blog’s monthly public opinion graphs available in one place by clicking the “Dashboard” link on the top of every page. If it doesn’t work for you, leave a comment that lets me know what browser you are using (I.E. versions seem to have particular problems) and I’ll be glad to send you an updated PDF. I’ll still be inserting graphs in posts, but this is one way to get the data up quickly without spending time on analysis, and maybe that will prevent me from being so late in posting the data.

Category: political parties

News and New Resources on Public Opinion in Slovakia

|

Update: Because of formatting problems with certain versions of Internet Explorer , this page is now available as a .pdf file: 2009_12_30 Pozorblog Public Opinion. |

I should begin with apologies for such a long hiatus and also with hearty congratuations to Monika Tódová of SME for writing one of the best articles on the process of public opinion polling in Slovakia: Prieskumy môžu politikov miast. It’s not very long but it finally addresses the problem of dueling headlines–“SaS/Most-Hid poised for success” v. “SaS/Most-Hid has no chance” (often in the same newspaper in the same week) and asks “How is it possible?” The answer lies in the ways that various pollsters survey the public, and it turns out (perhaps I should have known this) that FOCUS and MVK (and previously UVVM) offer a list of parties to choose from whereas Median gives no list. The latter method, of course, will tend to benefit those parties that are best known, while the former can give a boost to parties that are little known (and the process by which firms choose to add parties to their formal lists is fraught with difficulty.

The question now, is whether Todova’s article means a change in approach. Her article is the first instance I can remember outside of election campaigns when an article juxtaposes results from multiple pollsters. I can only hope that this will be the beginning of a trend even if (especially because) it might put this blog out of business. But I’m fairly secure that the time and space constraints of Slovakia’s papers will not let that happen and so there will be room for a blog obsessed with the minutiae of public opinion in Slovakia.

But just so that this blog does not immediately become obsolete, I want to share a new method I’m working on for displaying public opinion results. This is not quite ready for prime time, but using the Timeplot application developed as part of the astounding SIMILE project at MIT, it is possible to create dynamic charts that are fully modifiable and easily updated on the basis of simple text files. Of course that meant that I had to clean up my database, but now that that’s done, I should be able to present updated public opinion results with a minimum of effort (that’s the theory) and can even, theoretically, create a dashboard page on the blog itself for those who want to look at the numbers rather than read my analysis.

Below are examples of what is possible. I’m preparing a year end summary, so you’ll see these graphs again soon with some analysis attached.

Twenty Years Ago Today: Challenges to Democracy in Slovakia

As part of the 20th anniversary commemorations in postcommunist Europe, America.gov (one of the U.S. State Department’s outreach websites) has been soliciting academics and journalists to write on “Challenges of Democracy” in the region (in 400 words or less!). They were kind enough to publish my own thoughts (with no editorial intrusions) along with other comments about other countries from eminent commentators including Vladimir Tismaneanu, Janos Bugajski, Charles Ingrao and fellow Slovak Studies Association member Mark Stolarik. My own take on the question (utterly predictable to those who read this blog on occasion) is below, but read it here instead so as to let the managers of America.gov demonstrate to their superiors that the idea was worthwhile.

As part of the 20th anniversary commemorations in postcommunist Europe, America.gov (one of the U.S. State Department’s outreach websites) has been soliciting academics and journalists to write on “Challenges of Democracy” in the region (in 400 words or less!). They were kind enough to publish my own thoughts (with no editorial intrusions) along with other comments about other countries from eminent commentators including Vladimir Tismaneanu, Janos Bugajski, Charles Ingrao and fellow Slovak Studies Association member Mark Stolarik. My own take on the question (utterly predictable to those who read this blog on occasion) is below, but read it here instead so as to let the managers of America.gov demonstrate to their superiors that the idea was worthwhile.

Slovakia today faces several slow and subtle threats to meaningful democratic representation. These hardly seem dangerous when compared to the near-collapse of the Slovakia’s democracy in the mid-1990’s, but they are serious in their own right, especially because their subtlety makes them hard to see and even harder to correct.

Some current threats echo the problems of the 1990’s, particularly the growing politicization of the judiciary and other state functions and the sharpening of ethnic rhetoric. Questions of ethnicity in Slovakia are genuinely difficult, and it is no surprise that they remain at the center of political debate, but the shrillness of today’s exchanges risks long-term damage to relations between groups which have no choice but to live together. Although these problems are worrisome, Slovakia’s own recent history suggests that the cycle of alternating government and opposition tends to redress imbalances. Slovakia’s democracy survived worse periods of politicization and polarization, because Slovakia’s voters rejected extremes and opted for parties that offered more moderate alternatives.

But Slovakia’s political party system faces its own threats. Slovakia’s party system has become dominated by political parties which are less like classic European parties than like Internet startups: well-branded, CEO-driven organizations with a big-money investors, lots of consultants and short-term goals. They remain intact only as long as they continue to serve their function; otherwise they split or merge. Ordinary people become consumers, persuaded by flashy advertising campaigns to spend their vote on one product or another. These parties do not violate the formal rules of democracy, but the resulting interactions are thin and unsatisfying. In the worst case scenario, parties become vehicles for gaining office rather than for governing, and since they themselves do not expect to be around for more than one or two election cycles, they have little reason to pursue long-term and difficult policy changes. Faced with a parade of volatile new parties fighting for attention with famous faces and promises of renewal, voters become cynical about the political process and stop expecting that politics offers any solutions to public problems.

This problem is more akin to a chronic illness than a fatal disease. A sloppy, unresponsive, celebrity-driven democracy is still a democracy and can probably limp along indefinitely, but not without a huge cost in unsatisfied needs and wasted resources. Slovakia will not be alone in this—the same trends are emerging throughout the east and with only a slight lag in the west—but misfortune shared is still misfortune.

Reprinted from http://blogs.america.gov/democracy/2009/11/06/challenges-to-democracy-in-slovakia/

September 2009 Poll Results: Whither Smer?

This post comes a bit late because of changes to the pozorblog site but the month’s news is important enough to warrant an interim post.

Things only changed a little this month. But small changes from one month to the next add up. And this month not all the changes are small. A few areas to watch.

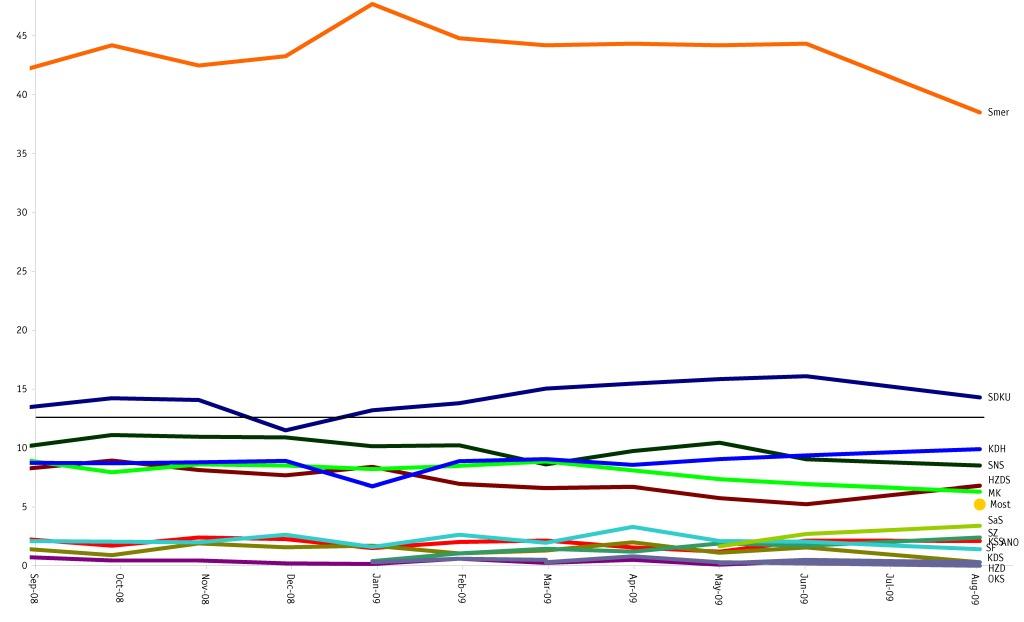

Smer

As the image shows Smer remains far above its nearest competitors–still well over double the preferences of SDKU. But the last four months have seen a drop in Smer preferences from the mid-40s to the high-30s. This shift is primarily in FOCUS polls, however, and it is difficult to say whether the result is “real” or some sort of blip. Median, the only monthly alternative, shows no similar drop. I am really missing UVVM this month as it was always helpful to see what a second pollster said before making a judgment, and MVK polls are as unpredictable–in their appearance, not their results–as weather.

Closer look at Smer polls over time show a gradual increase over the last two years peaking in a cluster in late 2008 and then reverting back to the previous plateau and now, again to a lower level, though whether that lower level is part of a plateau or a slope is something we will have to see about. I suspect next month will show Smer higher in Focus polls but lower than its average level for the last 5 months. I suspect this month’s drop is a bit of an outlier, just as its previous peaks did not always sustain themselves and appear to be noise rather than signal.Smer doesn’t have too much to fear–it’s still hard to calculate a way that it won’t be in the next government, but it wouldn’t surprise me if some mid-level Smer types were starting to work on their political insurance policies.

Closer look at Smer polls over time show a gradual increase over the last two years peaking in a cluster in late 2008 and then reverting back to the previous plateau and now, again to a lower level, though whether that lower level is part of a plateau or a slope is something we will have to see about. I suspect next month will show Smer higher in Focus polls but lower than its average level for the last 5 months. I suspect this month’s drop is a bit of an outlier, just as its previous peaks did not always sustain themselves and appear to be noise rather than signal.Smer doesn’t have too much to fear–it’s still hard to calculate a way that it won’t be in the next government, but it wouldn’t surprise me if some mid-level Smer types were starting to work on their political insurance policies.

SDKU and KDH:

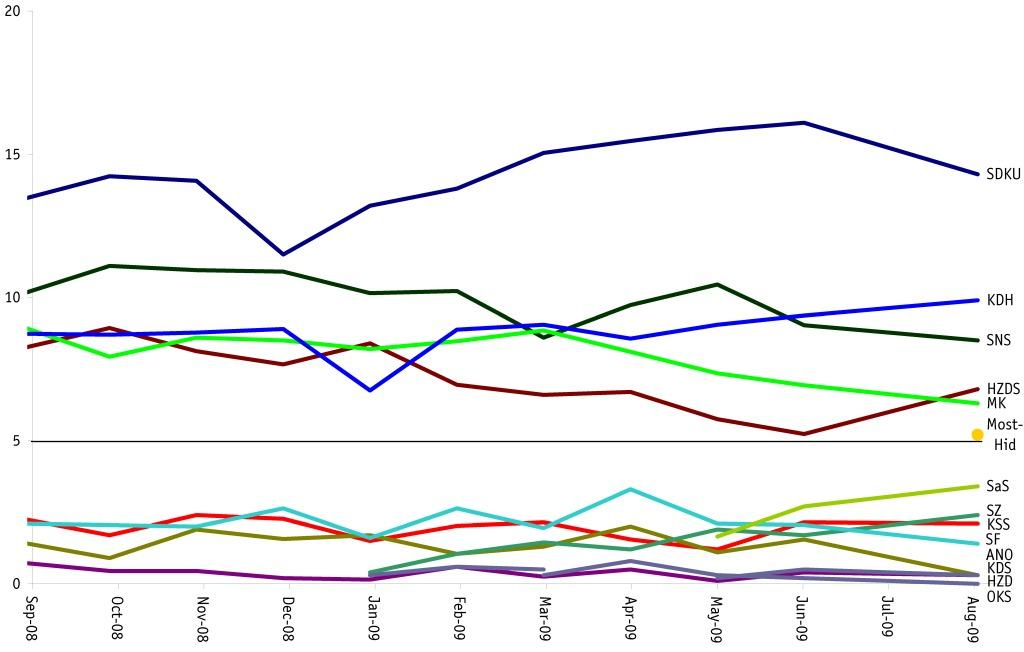

Take Smer out of the graph and it looks more like a competitive party system. And this fall for the first time in a long time, the two top competitors to Smer are both from the opposition: SDKU and KDH. SDKU dropped slightly this month in FOCUS polls but it’s still near a historic high (in the past it would do this well in elections but not in polls). Some of its slight decline may relate to the rapid resurgence of KDH, a party that has taken a sudden upward jump due, I must think, to the energizing presence of Jan Figel, former European Commissioner. I am interested to see whether Figel’s more proactive approach will keep the party preferences high. In some sense, this does not help the opposition much, since those attracted to Figel are probably those who would otherwise hold their noses and vote for SDKU, but since they might also vote for SaS, it keeps votes among the larger opposition parties. Thumbnails for SDKU and KDH are here:

Take Smer out of the graph and it looks more like a competitive party system. And this fall for the first time in a long time, the two top competitors to Smer are both from the opposition: SDKU and KDH. SDKU dropped slightly this month in FOCUS polls but it’s still near a historic high (in the past it would do this well in elections but not in polls). Some of its slight decline may relate to the rapid resurgence of KDH, a party that has taken a sudden upward jump due, I must think, to the energizing presence of Jan Figel, former European Commissioner. I am interested to see whether Figel’s more proactive approach will keep the party preferences high. In some sense, this does not help the opposition much, since those attracted to Figel are probably those who would otherwise hold their noses and vote for SDKU, but since they might also vote for SaS, it keeps votes among the larger opposition parties. Thumbnails for SDKU and KDH are here:

SDKU——————————————————– KDH

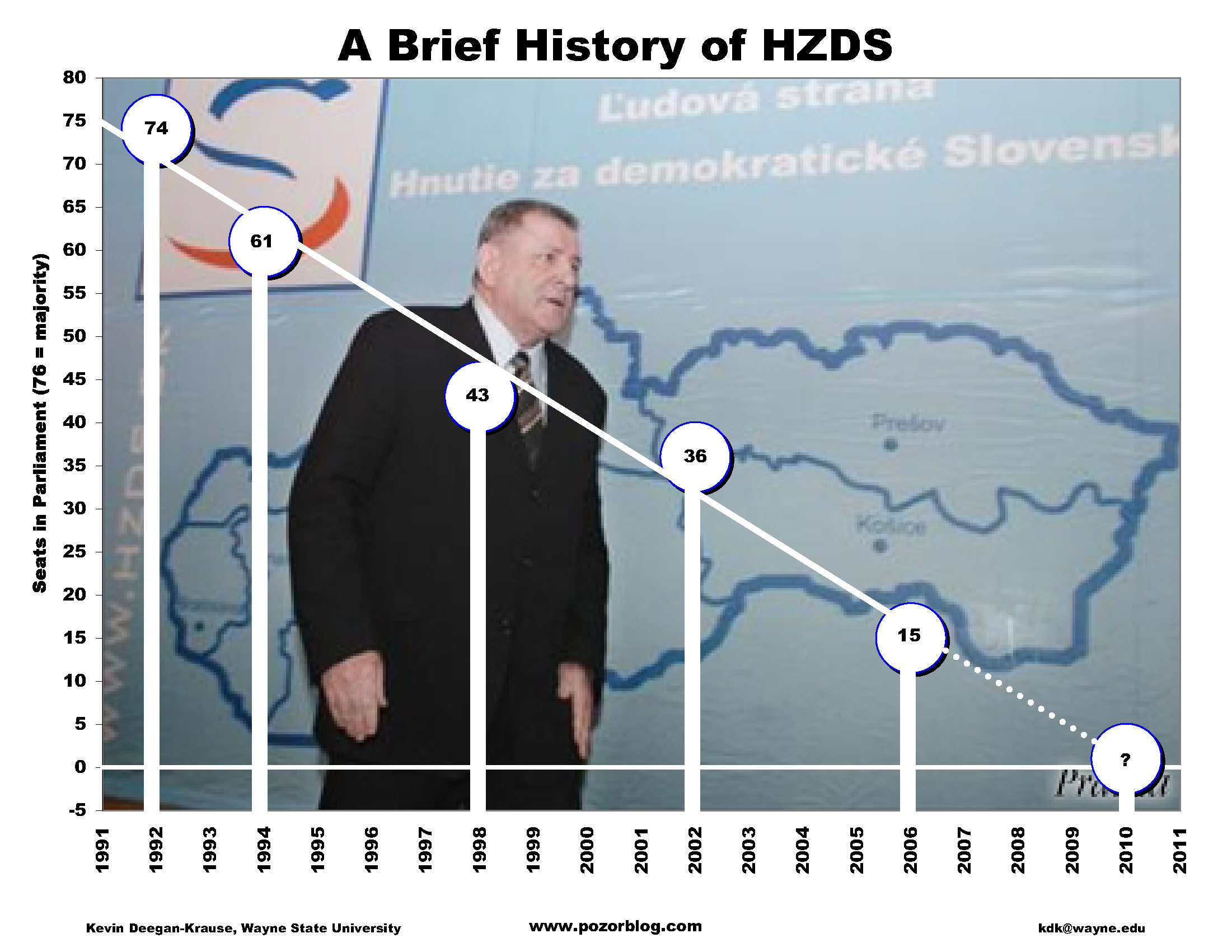

HZDS and SNS:

Slovakia’s two minor governmental parties continue their respective slow slides, partly the result of Smer’s remarkable skill at picking off their voters and partly the result of their own internal struggles and disadvantages. HZDS has stopped falling for the moment but given the party’s steady 10 year slide and absence of anything new that might recommend it, it is hard to imagine anything but continued decline (with the key question: 5% or not 5% next June). SNS’s decline has been disquised at times by the party’s erratic support shifts but it is notable that all of the trendlines (24-month, 12-month, 6-month and 3-month point down at almost the exact same angle). The party has more leeway for falling than HZDS but it is not immune, and at some point SNS mid-level leaders are going to need to decide what to do if they feel that Jan Slota is pulling them down. The party’s structures are so focused around the party chair that the only way to force change will be to leave, but the last time they did that the parties split the electorate 50/50 and neither got into parliament.

SNS——————————————————– HZDS

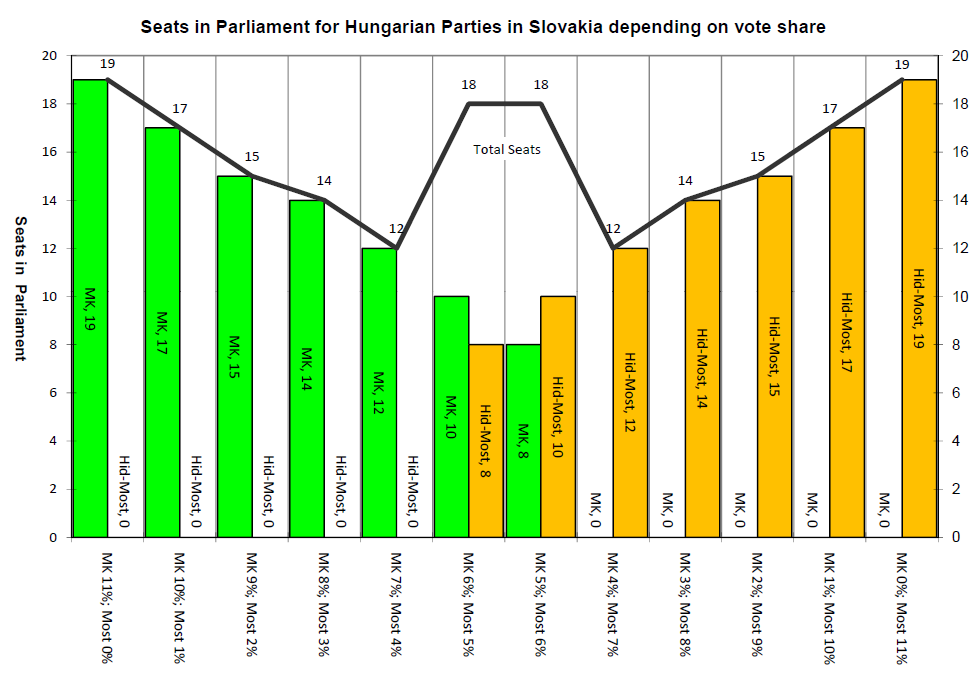

SMK and Most-Hid

Not much to say here, yet. For two polls in a row both parties are poised to make it into parliament. If this can continue then Bela Bugar has done a big favor to the Hungarian electorate, bringing back those disenfranchised from SMK. If both don’t stay above 5 and neither drops to near-zero, then the Hungarians will see their poorest electoral showing since the early days of Slovakia’s democracy. I’d be keen to hear any thoughts from Magyarophones about what to expect here as this is a subset of the population from which I hear little direct news.

SMK (regular graphs for Most-Hid coming soon)

Smaller Parties:

Not much news here this month. SaS shows staying power at around 3%, and KSS recovered this month to its traditional 3% levels as well (though it has not been there for awhile). Below, around 2% stands SF (recovering slightly from a major drop the previous month) and at at the flatline level are OKS, KDS, ANO and Liga (which didn’t get a single person to mention it’s name this month even though it’s on the list). Between them are two more: HZD (slightly higher than expected–it’s been flatlining) and the Greens (somewhat lower than expected–last month it even beat KSS).

What it all means? The Coalition Partner Game

It’s still Smer’s ballgame, but coalition politics could become extremely interesting if Smer does end up at around 35% and HZDS or SNS fall below 5%. It is dangerous to trust what parties say about potential coalition partners, but as of now, SDKU and KDH appear to have ruled out coalition with Smer (Dzurinda is right, I think, to note that such a coalition would severely hurt his party, and he doesn’t have the organization or track record to ride it out the way ODS and CSSD did with their opposition agreement in the Czech Republic). But if this option truly is gone, then there are few other combinations that can make 50%. If the existing coalition can’t muster 50% because one party drops off, then Fico would need to find alternatives, but (even though I generally do not rule things out) there will be no coalition containing both SNS and either SMK or Most-Hid, and SaS, the only other party that looks now to have a chance, has promised up one side and down the other that it will not join forces with Smer. So Smer’s only real chance is probably SNS+HZDS or so many votes for parties that fall below the threshold that it can with SNS or HZDS form a bare majority government.

At the same time, there’s not much hope for a government of the current opposition parties. Even with SDKU and KDH and SMK and Most-Hid and SaS, there’s nothing like a majority. It might be possible to create one by adding HZDS to this but even that’s unlikely and HZDS is the party in greatest danger of falling short. In 10 short years, HZDS has gone from a huge and polarizing force in Slovakia’s politics to a tiny but necessary coalition partners. The more things stay the same, the more they change.

August 2009 Poll Results: Bending The Mold

The pattern looks familiar and the lines haven’t changed much, but there are a few ways that this month’s results by FOCUS change our understanding of the current political competition.

The pattern looks familiar and the lines haven’t changed much, but there are a few ways that this month’s results by FOCUS change our understanding of the current political competition.

I have actually been fearing this change for a long time–not because of the actual politics involved but because of the emergence of a new party. The graphs in this blog are the product of a long and complex process of fighting with Excel to produce results that can be read by Google’s chart API (about which I understand little, but which is quite remarkable). That process has produced an elaborate set of calculations which are, unfortunately, based on the presumption of a certain set of parties (and only those parties) gaining election to parliament. This month holds quite a few big changes in public opinion and one of those–the emergence of Most-Hid with just over 5% of the vote–means that my old systems won’t work anymore. This is good news, in a sense, because it gives me the impetus to find a solution that will not require as much work (calculating in Excel, creating the google charts, posting separately to Google Docs), but for the moment it makes things more difficult. I will therefore resort to Excel charts for awhile. And now, after that pointlessly detailed introduction (I buried the lead again), the graphs and then some thoughts on anybody should care:

And the same graph without the distorting scale effects of Smer:

1. Most-Hid might make it into parliament

This may not be a surprise (Bugar is quite popular among Hungarians) but it is important, and the way the numbers fell is important in several ways:

- Most-Hid v. SMK is not exactly a zero-sum game. This month’s 5.3 score for Most-Hid came at relatively little cost to SMK which has dropped only about 1 percentage point in the last 4 months. Of course SMK has dropped quite a few percentage points since Csaky became party chairman (and even before while Bugar was still chair) but it would appear that the party has brought disaffected Hungarians back into the political system rather than stealing directly from SMK. As a result, Hungarian parties combined scored the best public opinion result that Hungarian parties have received in almost 5 years (since January 2005). All of the opposition’s gains this month can be traced to that single re-mobilization.

- Both can get into parliament. There has been some discussion about whether the two parties might split the vote down the middle (as SNS and PSNS did in 2002) and lose representation altogether. The results from today suggest that a 50-50 split is actually an ideal result for the Hungarian population in Slovakia. More worrisome would be a 60-40 split, cutting the Hungarian representation nearly in half. Of course there are some who suggest that infighting among Hungarian parties could disaffect enough to push Hungarian turnout so low that a 50-50 split would deny representation to both, but this month’s good results come after bitter conflict, so it is hard to imagine how bitter the conflict would need to become to provoke the worst case scenerio.

- Things are far from over. It may be that these two parties split the Hungarian vote. It is more likely that one will tend to prevail over the other, either Most-Hid because of more dynamic leadership or SMK because of stronger organization and tradition. This is one of the keys to the outcome of the next election so it bears considerable watching.

2. SaS has a (small) chance

This is something of a stretch because the party is only at 3.4%, but unlike the other small parties on the “right” it shows a positive trajectory. KDS has stalled below 0.5%, and Liga appears stillborn (in eight months of polls the party has racked up a total–not average, total–of 1.4%). OKS and ANO are effectively dead and DS and Misia21 exist only on paper (and barely there). The big loser in this is probably Slobodne Forum which looked to be doing well in late spring, but SaS’s much better performance in the Europarlament elections appears to have given it the edge. We have too little data to tell if it is a meaningful pattern, but SaS’s growth so far has been almost perfectly proportional to SF’s decline.

3. Smer’s recent decline continues

There is no real cause for gloom in the party (it is still almost three times the size of the next largest alternative) but it has dropped by nearly 10 percentage points from its (admittedly unrealistic) peak of early this year (when it was four times the size of the next largest alternative). Since the 2006 election the party has peaked and waned five times, so the variability is nothing new, but this is the first time that the party has dropped sharply from a plateau rather than from a peak. Of course it is safe never to rule out the possibility of recovery to new heights, but it is more likely that the weight of a poor economy and a large number of corruption scandals, some perhaps not so minor, have begun to take away some of the luster. This may not be a huge loss for the party as many of those shifting away are likely the supporters who wouldn’t bother to turn out to vote for it (as they didn’t in the Europarliament elections).

How it adds up (Smer’s threshold for success)

The big question is the intersection of the points above: the emergence of Most-Hid creates two parties that may or may not pass the 5% threshold. SaS adds a third. HZDS is the fourth (the party got a slight reprieve this month but even with that the 6-month, 12-month and 48 month trendlines show it dropping below the 5% threshold by spring and only the 24 month trendline puts above by about 0.5 percentage points, though the party’s loyal base also makes it necessary to adjust the numbers upward a bit in its favor). Since each of these parties could dispose of between 3% and 6% of the overall vote and since the magical 5% makes or breaks the party’s parliamentary representation, a lot will be riding on the results. My preliminary calculations suggest that in a worst case scenario for Fico–if SaS, Most-Hid, SMK and HZDS all made it into parliament–Smer would need 41% to be able to form a two-party government with SNS (assuming that SNS’s preferences do not also continue to decline), though it could also settle for a three-party coalition identical to the current one (and it could sustain that coalition even if its own preferences dropped as low as 31%). If HZDS failed to pass the threshold, Smer would gain some seats from the redistribution but not enough to overcome the loss of a potential coalition partner: if HZDS falls and both Hungarian parties and SaS survive, Smer would need all of its current 38% to form a two party coalition with SNS. Of course it is unlikely that all three of the smaller opposition parties would succeed. If one of them fails, Smer could get by with 33% and if two of them fail, the Smer could form a majority two-party coalition even if it got only 28%.

This all deserves more thought and calcluation. With any luck I will have opportunity to do just that.

Fico on Dzurinda: What it’s all about.

/* Style Definitions */ table.MsoNormalTable {mso-style-name:”Table Normal”; mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0; mso-tstyle-colband-size:0; mso-style-noshow:yes; mso-style-parent:””; mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt; mso-para-margin:0in; mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:10.0pt; font-family:”Times New Roman”; mso-ansi-language:#0400; mso-fareast-language:#0400; mso-bidi-language:#0400;}

While I do not often write about particular political statements, I am drawn to comment on today’s response by Robert Fico to Mikulas Dzurinda’s accusations that the government has failed to tap Eurofunds.

While I do not often write about particular political statements, I am drawn to comment on today’s response by Robert Fico to Mikulas Dzurinda’s accusations that the government has failed to tap Eurofunds.

I translate Fico’s statement as follows (and would appreciate any better translation):

My political conscience cannot be a person like Mikulas Dzurinda, who lies from morning until night. He gouged us, surrendered our economy to foreign monopolies, evidently bought members of parliament. A person who never wanted Slovakia, did not vote for the constitution of Slovakia or for sovereignty. I will never respond to such a person, ” said Fico

“Mojím politickým svedomím nemôže byť človek ako Mikuláš Dzurinda, ktorý od rána do večera cigáni. Vydieral nás, spôsobil odovzdanie ekonomiky tohto štátu cudzím monopolom. Preukázateľne kupoval poslancov Národnej rady SR. Človek, ktorý nikdy nechcel Slovensko, nehlasoval za Ústavu SR, zvrchovanosť. Tohto človeka nikdy nebudem komentovať,” povedal Fico.,Pravda, 6 August 2009

I have no interest in taking sides in this controversy, but the nature of the comment is worth some attention because, as sometimes happens (quite often in fact), a politician’s off-the-cuff remarks do an excellent job of summarizing how they think—and we too should think—about political competition.

Fico’s response follows this structure:

- A resolute moralism: “Dzurinda cannot be his conscience.” Fico is a man of strong moral opinion. He not only identifies his opponents as wrong, but also as morally flawed. This is not particularly unusual among politicians, but it is strong in Fico’s case. His is a tone of righteousness.

- An emphasis on corruption. Fico’s first observation about Dzurinda is that “he lies” Two phrases later, he reminds us of the scandals that were part of Dzurinda’s own period of government. These are important: not only was corruption an important theme for Fico (especially in 2002 but still to some extent in 2006) but his government’s own corruption scandals have caused the party to increase its emphasis on how bad corruption was under Dzurinda as a way of minimizing the current problems.

- An emphasis on economic injustice: “He gouged/stole.” Fico’s best theme has been the overreach of Dzurinda’s economic reforms. He has played this well and here he ties it in with the lying so that Dzurinda’s economic reforms presented not simply a different and incorrect economic formula but one which Dzurinda used for his own gain and with wanton disregard for (or indeed active malice against) the average Slovak.

- An emphasis on patriotism. Dzurinda not only hurt the economy but he did so deliberately to the benefit of foreign interests. Two phrases later Fico suggests an even deeper lack of national feeling in Dzurinda dating back to the early 1990’s. Dzurinda did not vote for the constitution (the final formal step toward independence), did not support “sovereignty” and did not even “want Slovakia” (phrasing which implies an even deeper antipathy than saying that he did not want “want an independent Slovakia.” The vehemence of this critique should not surprise me, but it does, as it is so deeply resonant of the critiques of Dzurinda’s then-party, KDH, in the 1990’s by Meciar’s HZDS (back when Dzurinda was a minor player), and particularly the word for sovereignty, “zvrchovanost” which had a particularly strong resonance for Meciar and his supporters. Meciar sometimes (though admittedly less frequently) applied similar critiques of lack of patriotism toward Fico’s then-party, SDL (back when he was a minor player). Now Meciar is all but out of the game, and it is Fico who is applying the critiques to Dzurinda.

All of fits nicely with what many of us have discussed and claimed: Slovakia’s party system has at least two dimensions—one economic, one national—and the last 20 years have been a competition to see which one would be most important. Meciar turned the axis in the direction of the national and held it there for most of the 1990’s. Dzurinda turned it back primarily to the economic and held it there for the first half of the 2000s, with Fico providing a big assist. Now in government, Fico has sought to shift the basis of competition by a half turn, linking the economic with the national so as to produce a single axis of competition between pro-national, economically statist parties on the one hand and non-national, pro-market parties on the other hand. The positions of the players differ slightly: The Hungarian parties push hard on national issues and care little about economics (but tend to be a bit more market oriented, a legacy from its past coalition partners and internal debates) whereas SDKU pushes some economic questions and stays away from national issues at all costs. On the other side SNS pushes hard on the national side and cares little about economics whereas Smer still pushes economic questions and plays slightly softer and more socially acceptable national issues. Whether this is permanent is an open question (like all questions I ask about Slovakia’s future…I’ve been wrong too many times), but for the moment Fico has hit on a winning formula and has no need to change it.

Other issues fight for prominence—some in KDH and all in KDS would like to see an emphasis on moral values, new parties and some in Smer continue to emphasize corruption—but these have yet to take hold in a fundamental way. The values question probably has too little traction, for most Slovaks outside the (demographically declining) population of believers. The corruption question is too hard to sustain because parties that get into power have a difficult time staying clean (and would have a difficult time persuading voters that they had stayed clean even if they could).

Finally, two off-topic (but maybe not so minor) points:

- It may or may not be a coincidence that he uses almost the same formulation—“from morning until night,” that Hungarian premier Gyurcsany used to describe his own party’s actions. Comparing Dzurinda to a Hungarian would be a nice touch, but it may simply be a coincidence.

- I am slightly shocked by Fico’s use of the word for lying—“ciganit”—which, though I may be mistaken, I do not recall hearing often from the mouths of politicians. Not only is this particularly rough language but its relationship to the slang term for Roma, “cigan” makes it potentially problematic. I know the word has taken on something of an independent existence in Slovak (much as “gyp” did in English) but it is hard to avoid the connection and it seems to be a word to avoid using. It is perhaps particularly troubling to me because at a language law rally outside of parliament in 1995 I overheard a Meciar supporter talking to a friend about Dzurinda (at that moment speaking on the floor of parliament against the restrictive language law) and saying “Did you know he’s a Gypsy? (“cigan”). Fourteen years later Slovakia has a new, relatively restrictive language law and Dzurinda is again likened to a “cigan” in the worst sense of the word.

In HZDS is everything possible

Except, perhaps, victory.

Today brings more news from the ever-shrinking HZDS: last week it was Sergei Kozlik with criticism; this week it’s Zdenka Kramplova (see below). The cost of criticism is lower now that HZDS has several times breached the threshold of electability: why refrain from criticizing a party that won’t get elected anyway. Kozlik is safely in the European Parliament for another five years. Kramplova won’t make it onto the party list of a party that may not make it into parliament. For them, it seems, it may be time to leave the heavily-listing ship. To its credit, HZDS may have managed one of the steadiest declines of any party anywhere, as if the Titanic had sunk so slowly that it managed to limp into New York harbor. Except that for HZDS there is no harbor.

Meanwhile I learn new Slovak words every time SNS chair Jan Slota speaks. This time the comments concern Smer’s Monika Benova-Flasikova (SNS vice-chair Anna Belousovova had something equally sharp to say about Benova-Flasikova last week)

———————–

“Kramplova not yet out of HZDS”

http://www.sme.sk/c/4902546/kramplova-zatial-z-hzds-neodchadza.html

In (babel) English here:

“HZDS is like a hamster in a wheel.”

http://spravy.pravda.sk/kramplova-hzds-je-ako-skrecok-v-kruhu-dwk-/sk_domace.asp?c=A090623_113718_sk_domace_p29

Something resembling a translation here:

“Slota: Benova is a stupid [goose]”

http://hnonline.sk/slovensko/c1-37543370-slota-benova-je-hlupa-husicka

Google tries here

European Parliament Elections: The Wonder of Wikipedia

Wikipedia hosts not only basic factual information regarding the recent elections but excellent analysis as well, particularly regarding the relative efficacy this time of preference voting with 3 out of 13 getting positions thanks to preference voting: Zaborska (KDH), Mikolasik (KDH) and Paska (SNS–though helped perhaps by his famous Smer namesake?). Full information is here.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/European_Parliament_election,_2009_(Slovakia)

Thanks to a reader for pointing it out and…I suspect…for providing the said analysis.

New Parties: SaS does the electoral math

Interesting post today from Richard Sulik, founder of Sloboda a Solidarita (trendily-colored logo is at left, found not on a party website but on a Facebook page), who responds to the charge from SDKU that SaS hurt the right by causing voters to “waste” votes on a party that did not make it over the threshold (http://richardsulik.blog.sme.sk/c/196401/SaS-oslabila-pravicu.html).

Interesting post today from Richard Sulik, founder of Sloboda a Solidarita (trendily-colored logo is at left, found not on a party website but on a Facebook page), who responds to the charge from SDKU that SaS hurt the right by causing voters to “waste” votes on a party that did not make it over the threshold (http://richardsulik.blog.sme.sk/c/196401/SaS-oslabila-pravicu.html).

Sulik makes interesting arguments to suggest that SaS voters had good reason to vote in other ways and that they might not have voted at all, but he also makes good use of electoral math to make his point: he uses the electoral formula to show that reallocation of all SaS to SDKU would only have reallocated the number of seats that went to the right (SDKU would have gained one but KDH would have lost one) and thus that SaS did not impact the final result. The math looks solid to me and it is nice to see someone respond to arguments by looking at actual numbers and rules.

Nevertheless, it is not as easy to dismiss the SDKU arguments if they are seen as a warning about future elections. SaS did not have much impact in the European Parliament elections because there were so few seats at stake (13 [Correction, thanks reader “Richard”). Had it been a parliamentary election (and yes, many other things would have been different as well), Sulik’s argument is not quite as strong. I’ve reworked his numbers assuming the 150 seats of Slovakia’s parliament at stake. According to this, calcuation, SaS would have had a significant impact on SDKU votes (which would have gained 6 seats had it received all of the SaS votes) which is partially but not completely ameliorated by its impact on KDH and SMK (each of which would have lost a seat). In terms of coalition and opposition, this is almost a crucial difference: from clear parliamentary majority for Smer-SNS-HZDS to a bare majority that would hinge on the decision of only two deputies.

European Parliament Election Results if 150 seats (the Slovak Parliament) were available for election, according to two hypotheses:

| Party | SaS supporters vote for SaS | SaS supporters vote for SDKU |

| Smer | 56 | 53 |

| SDKU | 30 | 36 |

| SMK | 20 | 19 |

| KDH | 19 | 18 |

| HZDS | 16 | 15 |

| SNS | 9 | 9 |

| Smer+HZDS+SNS | 81 | 77 |

| SDKU+SMK+KDH | 69 | 73 |

Of course this is all theory, but the underlying debate is deeply relevant. The more the fragmentation on the right, the worse it is likely to do (as the left and the Slovak nationals demonstrated in 2002), but it is not a zero-sum game and it may be true that Sulik’s party brings out new voters. His ability to mobilize certainly is apparent in this election. The question for me is whether the best use of Facebook/youtube/social networks is enough to attract the 115,000 voters who will likely be necessary to get a party over the 5% threshold in 2010? The effort is certainly worth watching.

New Parties: Most-Hid now on display

For a party whose name looks in English to mean “least visible” this party will be getting a lot of attention over the coming year. Founded by Bela Bugar, former head of the Party of the Hungarian Coalition (SMK), it may change Slovakia’s political landscape. Or maybe not.

For a party whose name looks in English to mean “least visible” this party will be getting a lot of attention over the coming year. Founded by Bela Bugar, former head of the Party of the Hungarian Coalition (SMK), it may change Slovakia’s political landscape. Or maybe not.

The party’s name actually means “Bridge” in both Slovak and Hungarian. This allows a nice pun by SME–“Bugar’s people divide Hungarians with a bridge (http://www.sme.sk/c/4881801/bugarovci-rozdelili-madarov-mostom.html)–and prompts a lot of speculation by a lot of people about the nature of the new party. In fact, I suspect that it would be difficult for any predominantly Hungarian party to attract more than 1 or 2% of the Slovak electorate, though European election results from this weekend suggest that minority-focused parties can attract more than their ethnic share if the other parties are in bad enough odor. Nor do I think that the new party, despite its name, necessarily expects to gain a large number of Slovak voters. The debate here is primarily about what happens within the Hungarian community.

At first glance, creation of a second major party to represent Slovakia’s Hungarian minority seems extremely dangerous in a country where the electoral threshold is 5% and the Hungarian population hovers around 11%. The Slovak National Party (SNS) here represents the worst case scenario: in 2000 it split its 8% electorate almost exactly down the middle (disillusioning a few of its supporters in the process) between SNS and the “Real” SNS (PSNS) in such a way that each half got 3.5% and neither made it over the threshold. With this example in mind, the establishment of Most-Hid looks like a gamble, especially since, the split follows the SNS-PSNS in another key way: one party gets the more popular leader but little organization, while the other gets the organizational continuity and the uncharismatic new leader who threw out the other one. The difference, however, is significant as well: unlike SNS voters (who could always turn to HZDS) Hungarian voters do not have anywhere else to go, and given the minority status of Hungarians in Slovakia they are relatively well-habituated to turning out rather than staying home.

Given these conditions, what is the likely effect of Most-Hid on overall election results. Well in the first place, Bugar has been careful not to exclude the possibility of an electoral coalition with the party he just left, which would more or less return the situation to the pre-1998 situation in which two Hungarian parties competed for share of vote but approached elections in coalition. Even if the parties do go into the election separately, the results may actually not be catastrophic for the Hungarian population. The graph below starts with today’s electoral environment and makes the assumption that a combination of two Hungarian parties will receive 11%. (This is a conservative estimate, slightly below the party’s recent totals in the mid-11% range. Of course it is possible that bitter competition between two Hungarian parties could turn voters off, but it is just as possible that having more defined choices might bring some Hungarians back to the voting booth and, just maybe, that Bugar could attract a few Slovaks, so 11% is probably a bit low.) Under current conditions, a party with 11% would gain 19 seats, one short of SMK’s take in 2006. For the sake of argument I assume that each point gained by Most-Hid reduces the support for SMK by the same amount and then calculate the number of seats according to the current Slovak method for alloting parliamentary seats:

First, and obvious but it should be said, unless the Hungarian party electorate falls below 10%, the emergence of Most-Hid won’t replicate the SNS-PSNS mutual destruction. One of the two parties will gain representation. The next-worst-case scenario not impossible but it is also not as grim as it might seem because of the workings of the electoral system. If Most-Hid (or SMK) were to get 4.99% and the other party 6.01%, the total share of parties would certainly fall short of the possible score, but not by as much as one might suppose since, with fewer parties above the threshold, parties get more seats per vote. As a result, the likey minimum score for total Hungarian representation is 12 seats. Furthermore in half of the scenarios above (I cannot say which is most likely), Hungarian representation does not drop by more than two.

The fact that the creation of Most-Hid threatens a drop but not an elimination of Hungarians in parliament may help to explain Bugar’s calcuations. The step won’t ruin his reputation and increases his options. It is not impossible that Most might be able to attract a significant share of SMK support and become the dominant of the two partners, allowing Bugar to dictate terms, allowing the possibility of an electoral coalition with SMK, even leading to the ouster of Csaky from SMK and a re-unification under Bugar.

Add to this the probability (diminished slightly but still extremely high) that Smer will form the next government and the fact that some within Smer have already responded positively to Most-Hid’s creation (http://spravy.pravda.sk/smer-chvali-bugara-sdku-stoji-za-csakym-d94-/sk_domace.asp?c=A090610_085204_sk_domace_p23) and the creation of the party actually looks like a well-calculated risk. Even the timing is relatively good: a year ahead of elections is enough for the party to build an organization but not too long for the party to languish in opposition obscurity.

Smer may be the real winner in all this: if Most makes it over the threshold, the number of possible coalition partners increases and therefore so does Smer’s bargaining power. If Most does not make it over the threshold but draws away a significant number of voters from SMK, then the seats SMK might have won are redistributed upward and some of them will go to Smer.

The real loser in this are those political scientists (by which I mean myself) who argued that SMK’s strong internal organization and decision-making mechanisms made it more stable and less likely to fragment. But perhaps those same researchers can recover by shifting their focus to study new parties.

—–

One interesting side note: at the time of with the rather poorly-planned announcement of Palko’s KDS, which at the time had neither a website, logo or even name, I have been conscious of how politicians in Slovakia miss chances for using early publicity to establish a brand that no private firm would ever miss. So on the day the rumors about Most-Hid finally reached the daily press I checked to see if anybody had established a Most-Hid website. No, but they did do so by the following day, though the website is empty except for the logo.

Interestingly if I read Whois.com right, the party had already claimed the domain name about 3 weeks ago, at a time when discussions between Bugar and Csaky were still going on! Plus two points for prior planning. Minus one point for good faith bargaining.

Domain-name hid-most.sk [and most-hid.sk] Admin-name Websupport, s.r.o. Admin-address c.d.457, Kysucky Lieskovec 02334 Admin-telephone 0904/306 081, 0904/306 081, 0904/306 081 Last-update 2009-05-16 Valid-date 2010-05-12 Domain-status DOM_OK