Another year, another election. This time a joint work by Tim Haughton and Kevin Deegan-Krause reviewing Slovakia’s most recent election and what it means (even for people who can’t find Slovakia on a map). Tim Haughton (not pictured here) is Austrian Marshall Plan Foundation Fellow, Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies & Senior Lecturer in the Politics of Central and Eastern Europe, University of Birmingham. Kevin Deegan-Krause is Associate Professor of Political Science, Wayne State University, Detroit Michigan.

Keeping a careful eye on Slovakia's elections. Photo courtesy of Reuters (http://bit.ly/yDQg55).

Slovakia’s 2012 election never seemed to hold much room for surprise. The Wall Street Journal forecast Slovakia Center-Left Party Headed for Election Victory, the Financial Times watched as Slovakia coalition heads for defeat and nearly every major newspaper and news service said the same thing: power in Slovakia would change hands from right to left on March 10, 2012.

And so it did, but a look inside Slovakia’s election helps to make a simple story somewhat more complex and even offers a few insights into 21st century-style democracy for those who do not have much interest in Slovakia itself.

What happened in the election?

The left won; another new “party” erupted; everybody else lost

- Left over right: For the first time in the country’s history a single party won a clear majority in the elections. The left-leaning (and sometimes nationally-oriented) Direction-Social Democracy (Smer-SD) led by Robert Fico won 44.4% of the vote and 55.3% of the 150 seats in Slovakia’s parliament). Fico supplanted a four-party right-leaning coalition that took power in Slovakia in 2010 with a narrow majority (replacing Fico, who had governed from 2006 until 2010) whose internal disagreements over the Greek bailout led to a vote of no-confidence in the coalition’s prime minister, Iveta Radicova, and early elections.

- Decline of Slovak-national parties: Slovakia’s 2012 elections witnessed the continuing collapse of parties emphasizing the Slovak nation. In 2012 the Slovak National Party (SNS) failed to exceed the country’s 5% electoral threshold and followed in the 2010 footsteps of its former partner the Movement for a Democratic Slovakia (HZDS), the once-mighty electoral machine of Slovak politics which this year could not muster even a single percent.

- Split among Hungarian-national parties: On the other side of Slovakia’s national divide, the Hungarian vote split nearly evenly between the Party of the Hungarian Coalition (SMK), which fell just below the 5% threshold, and Bridge (Most-Hid) led by a longtime former SMK chairman, which managed parliamentary representation with a 7% showing.

- Novelty on the right: Finally as in every Slovak election but one (2006), a newly created party succeeded in crossing the threshold and entering parliament—the evocatively named “Ordinary People and Independents” (OLaNO). Furthermore all right wing parties experienced shifts akin to the “defenestration” of Civic Democratic Party (ODS) leaders in the Czech Republic’s 2010 elections, as voters made significant use of preference voting to rearrange party lists and elevate new, seemingly cleaner candidates over less than angelic party regulars.

What happened in the campaign:

The left ran smoothly; the right ran into a gorilla; the rest ran into each other

As with the results themselves, the world’s news sources had little doubt about the reason: corruption. Reuters offered an explanation for the apparently clear outcome: Slovaks set to dump centre-right after graft scandal. Yet the actual circumstances are more complicated. Surveys suggest that the right-leaning coalition lost the support of the majority of voters only a few months after taking office in the summer of 2010, and by mid-2011, Fico’s Smer-SD was consistently polling at levels sufficient for a one-party parliamentary majority, well before the collapse of the coalition over the Euro-bailout or the scandals surrounding the so-called “Gorilla” file.

Prediction came easily in Slovakia’s 2012 election in part because the narrative of the two campaigns followed such clearly divergent paths. On one side, Robert Fico’s Smer-SD managed to avoid any mistakes. In part it succeeded in this because it took almost no risks running a similar campaign to those in previous elections; it managed to avoid significant taint (even in scandals that concerned some of its own members) and its campaign relentlessly pushed the key word “certainty” (istota), and maintained a unified, calm and confident (but not cocky) voice all the way through.

Standing in sharp contrast were the efforts of all nearly of Fico’s competitors. The election campaign itself was often overshadowed by large-scale demonstrations provoked by the “Gorilla scandal,” so called after the leak of the eponymously-named police file purportedly highlighting intimate links and lucrative mutually-beneficial deals between financial groups and politicians, especially those in the 2002-2006 government. Gorilla, along with allegations that MPs had been offered bribes in return for their loyalty in the fractious vote for the prosecutor-general in 2010, served to indict nearly the entire political class and its murky links with business and produced several vehement demonstrations in Slovakia’s major cities.

Although Gorilla and similar scandals cast shadows over all political leaders, the main victim was the leading government party, the Slovak Democratic and Christian Union – Democratic Party (SDKU-DS), and its leader Mikulas Dzurinda. SDKU also suffered from the decision of its prime minister, Iveta Radicova, to leave politics after her frustrating experience of trying to hold together a fractious coalition in which even her party colleagues Dzurinda and Ivan Miklos were not always safe allies. Dzurinda, a two-time prime minister (1998-2006) and foreign minister (2010-2012), liked to remind voters that it was his governments that took Slovakia back into the European mainstream after the illiberalism of the Meciar years, but faced struggles of his own. In 2010 a different scandal forced him to relinquish his top spot on the party’s election list (a position taken by outgoing prime minister Radicova); in 2012 he regained the top ballot position but not the affection of his party’s voters. In the wake of “Gorilla,” Dzurinda received the preference vote support of only one sixth of his own party’s voters (a drop from 165,000 in 2006 to just 27,000 in 2012) and ceded the leadership of the party—which he had held since its inception—to reformer Lucia Zitnanska.

Leadership change does not appear to be on the table for the Christian Democratic Movement (KDH)—the only other party in Slovakia’s parliament that has not had the same leader since its foundation—but this party, too, saw a shift in preference votes toward younger and more energetic figures including party vice-chair Daniel Lipsic. The party did not lose strength in this election, but its reliance on its loyal electorate and its weak campaign (encapsulated in the ill-judged slogan ‘white Slovakia’) prevented it from capitalizing on SDKU’s woes and taking clear leadership on Slovakia’s right.

Also on the right—but from an economic rather than a cultural perspective—Freedom and Solidarity (SaS) was only narrowly able to scrape past the 5% threshold. The party suffered from pre-election revelations that party leader Richard Sulik held monthly meetings with dodgy businessmen, but managed to hang on to enough voters through its unique combination of libertarian morality and pro-market values and its prominent negative stance on the Euro bailout (a position so important to Sulik that he allowed his opposition to bring down the government of which he was a part).

Among other parties, neither of the two major Hungarian contenders faced a similar taint (although Bugar’s links with businessman Oszkar Vilagi were mentioned on several occasions) but neither could boast of particular accomplishments or a particularly noteworthy campaign. On the other end of the national spectrum the Slovak National Party did manage a noteworthy campaign, but only by pushing the boundaries of decorum. In its 2010 campaign, SNS projected aggressively xenophobic images of bandit Hungarians and indolent Roma with (photoshopped) chains and tattoos. In 2012 the party abandoned any pretense of style and embraced raw confrontation, borrowing liberally from anti-Semitic caricature and even internet pornography (one billboard featured a female model wearing only an EU-flag thong and the message “the EU is screwed.”)

http://www.heraldica.org/topics/national/czech.htm and http://www.thedaily.sk/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/obycajni-ludia-znak.jpg

Weak performance by major parties in Central and Eastern Europe seems more often than not to benefit brand new parties, a phenomenon common to Slovakia but now apparent also in Hungary (Jobbik, Politics Can Be Better), the Czech Republic (Public Affairs, TOP09), Poland (Polikot’s Movement), and Slovenia (Jankovic’s List, Virant’s List). In 2012 Slovakia again produced a new parliamentary party, but stopped short of producing two. Igor Matovic, elected unexpectedly in 2010 through preference votes on the SaS party list, tentatively positioned his new “Ordinary People and Independents ” party on the right-hand side of the spectrum, but took full advantage of the corruption scandals (including a revision of the Slovak seal replacing its hills and cross with a similarly-shaped gorilla and banana) .

A second new party, evocatively called “99%” briefly succeeded in attracting voters with a well-designed and lavishly-funded campaign (including one of the first to use a legal loophole to air paid-television commercials), but quickly lost momentum as questions emerged about the source of the lavish funding and the possibility of systematic falsification of signatures on the party’s establishing petition. With its final tally of only 1.6% of the vote, 99% suggests that there are limits on the degree of artificiality that even the most disillusioned voters are willing to accept from a new anti-corruption, anti-elite party.

What stayed the same?

Despite the shift in seats, the relative vote share of electoral blocs changed little.

Although the world’s news sources explained their election predictions on the basis of the corruption scandals—Reuters suggested that Slovaks were “Slovaks set to dump centre-right after graft scandal”—the actual footprints of the gorilla-scandal appear to have been relatively shallow. While it certainly had individual and institutional effects, toppling Dzurinda and helping to rearrange the complexion of parties on the right, the scandals actually produced no little change in the overall array of Slovakia’s parties. Surveys suggest that the right-leaning coalition lost the support of the majority of voters only a few months after taking office in the summer of 2010, and by mid-2011, Fico’s Smer-SD was consistently polling at levels sufficient for a one-party parliamentary majority, well before the collapse of the coalition over the Euro-bailout or the scandals surrounding the so-called “Gorilla” file.

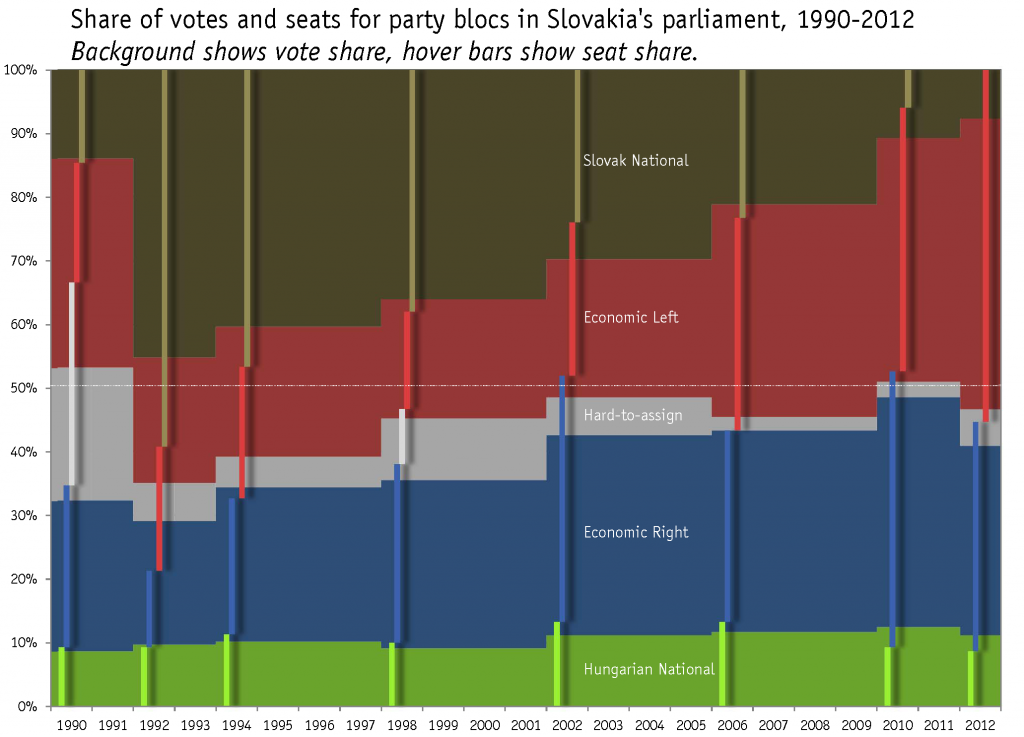

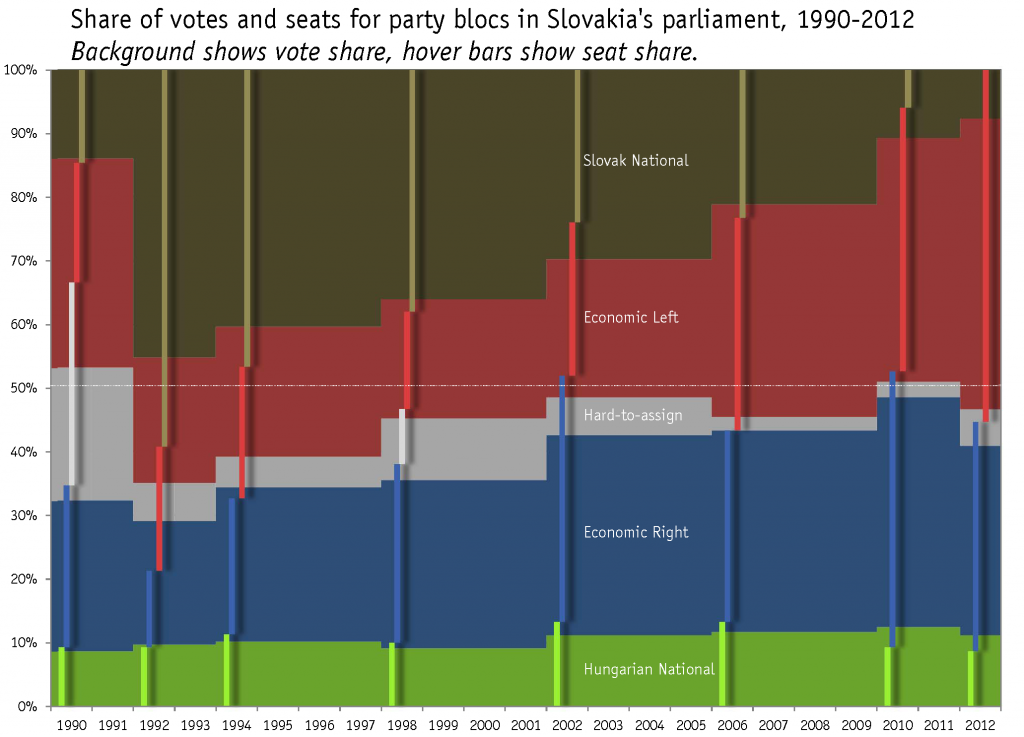

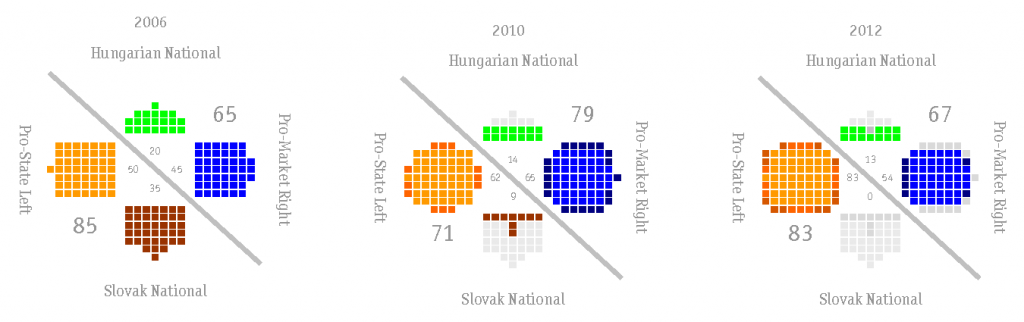

Share of votes and seats for relevant political blocs in Slovakia. Click image to enlarge.

When we delve deeper into Slovakia’s results over time we see that frequent changes in party and government obscure a remarkable degree of stability within the electoral blocs. The figure here shows the development of both Slovakia’s electorate and its parliamentary representation over time, beginning with the assumption of four relatively distinct electoral blocs: left and right, and Hungarian national (those of Hungarian ethnicity) and Slovak national (those of Slovak ethnicity for whom ethnicity is particularly important). The figure shows an extremely high degree of long-term stability of bloc-voting levels on Slovakia’s right and among the Hungarian national parties. Whom these voters vote for (indeed, which party is even on the ballot) has changed significantly over time, but the relative percentage in these two categories has not changed by more than a few percentage points over the four elections of the past decade (and not much before that). In the other half of the political landscape, there are more significant shifts—the decline of the Slovak-national parties and the rise of the economic left, but these two developments are almost perfectly reciprocal, and the overlap of themes suggests a high degree of compatibility between the voters in these two blocs.

The horizontal mid-line of the graph suggests that unlike the combination of left and Slovak-national parties, the coalition of right and Hungarian-national parties has never actually constituted a majority of Slovakia’s voters. The right has been able to form coalitions only when allied with the left (as for a brief time in 1994 and again from 1998 to 2002) or benefited from fragmentation among left and Slovak-national parties that kept some of them from passing the 5% threshold and produced a disproportionate number of seats for the right (as between 2002 and 2006 and again, to a lesser extent between 2010 and 2012). In the 2012 election, threshold failures by parties on both sides produced a roughly even redistribution of seats which benefitted the larger combined bloc, that of the Slovak-national and left, and because of the collapse of the Slovak-national parties, and consolidation of the left, this space was occupied entirely by Robert Fico’s party, Smer.

What changed?

Despite stable vote shares, some blocs lost seats when small parties fell below the 5% threshold.

The dynamics of public opinion are always filtered through the institutions of electoral politics and in Slovakia those institutions have recently made the difference between winners and losers. Party change more than voter change has produced most of Slovakia’s recent political volatility.

As an example, of such “supply-side” volatility, it is worth noting that while Slovak-national parties have disappeared from parliament, the Slovak-national party vote has actually changed relatively little. Together, parties which appeal to the Slovak-national themes managed to win nearly 8%, only about two percentage points less than what they achieved two years ago. As with most other changes in Slovakia’s politics, the collapse of parliamentary representation for the Slovak-national bloc lies in the interaction between party splintering and the 5% threshold. Although perhaps less decisively than in 2002, when SNS also lost its representation in parliament, a splinter from SNS led by a former leader may have pulled away a vital share of the SNS vote, and another radically anti-Roma and anti-immigrant party with roots in the skinhead subculture may have done the same. The 0.6 won by the breakaway Nation and Justice (NaS) or the 1.6 won by the People’s Party-Our Slovakia (LS-NS), would have been sufficient supplement to the 4.6 won by SNS to take the Slovak-nationalists back over the threshold and into parliament. It is possible that a new leader could emerge to replace Jan Slota in SNS or that a new national party could supplant SNS entirely, but with Slota’s party still dominating the (vastly diminished) national bloc and with Slota still dominating his party, it is difficult to see alternatives in the short term.

Similar institutional conflicts have affected parliamentary representation on the Hungarian-national side. Although the landscape of the Hungarian voters in Slovakia has long been complicated by division into multiple parties and factions (as befits a national community with a population larger than Luxembourg or Iceland), in electoral contests, Hungarians tended to band together during elections, forming electoral coalitions or even common party structures to maximize the gain above the electoral threshold. That changed with the breakaway in 2009 of popular former party leader Bela Bugar and his new party Most-Hid. Since the Hungarian parties tend to garner between 11% and 12% of the vote, there is a relatively narrow window in which two competing parties can both exceed the 5% threshold. In both 2010 and 2012 only Most-Hid managed to attract more than 5%, in part because of its more moderate stance on national questions and the ethnic Slovaks attracted by Bugar. Its rival, the Party of the Hungarian Coalition (SMK) fell in both 2010 and 2012, each time by less than 1%. While the competition between the two parties may help to keep them responsive to the electorate, it also cost the Hungarian population 2/5ths of its potential representation in parliament. Whether two successive losses like this can produce a rapprochement between the parties before the next election will depend on the concessions that either side is willing to make in the interest of overall Hungarian representation. So far that willingness has been quite small and Bugar’s complaints of a “dirty campaign” waged against him and the clear preference of Viktor Orban and the Hungarian government for SMK make a rapprochement unlikely in the short term.

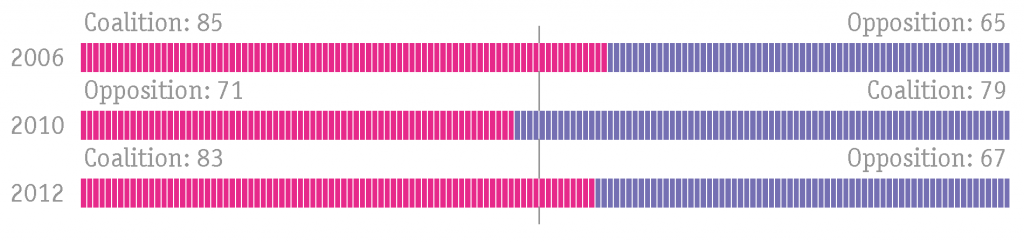

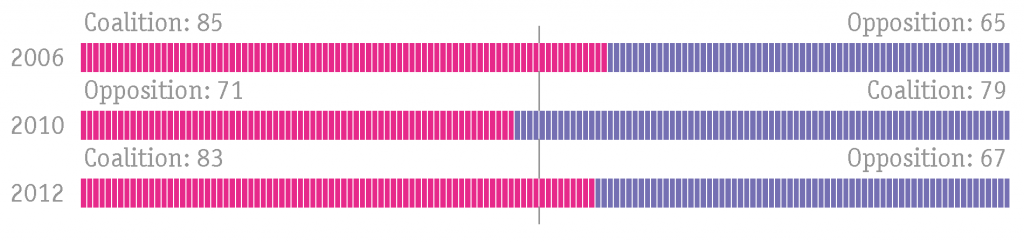

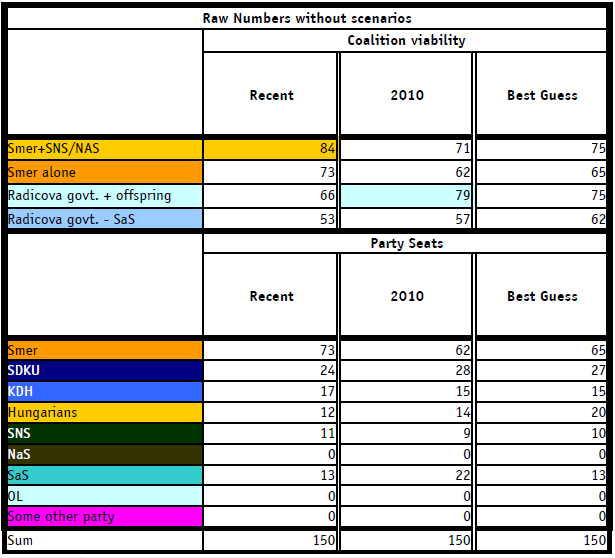

An even bigger challenge awaits Slovakia’s right. Outside observers (and quite a few domestic ones) blame the right for losing the 2012 election, but as the figure above suggests, its combined vote was not much worse than in 2002 or 2006. The figure below indicates that its seat total was actually somewhat higher than in 2006.

In retrospect, the exceptional election for the right may have been not 2012 or 2006 but 2010. In that year, four years of Fico government, with some sizeable scandals, sent some moderate, anti-corruption Smer voters across bloc lines to vote for anti-corruption right wing parties such as SaS. In 2012, by contrast, the right parties were the target of anti-corruption motivated votes and some migrated (back) to Smer, while others left for Ordinary People or a host of small new parties which had (so far) avoided the taint of the major parties.

The main source of Fico’s victory may thus lie in his ability to calmly preserve his party’s unity and wait for the return of former voters or the arrival new ones as the right parties sawed off their own limbs. Fico secured near complete dominance of a large part of the political spectrum, consolidating the left under his leadership and attracting the support of the more nationalistically-inclined voters, especially those from his erstwhile coalition partners, the SNS and Meciar’s Movement for a Democratic Slovakia (HZDS), parties whose demise he at times helped encourage. In 2010 this cost him the premiership when it left him without a strong enough coalition partner to form a government, but in 2012 it actually helped increase his parliamentary majority since seats not going to SNS went 5-in-9 to his own party (based on a hypothetical situation in which SNS received 5.01% of the vote).

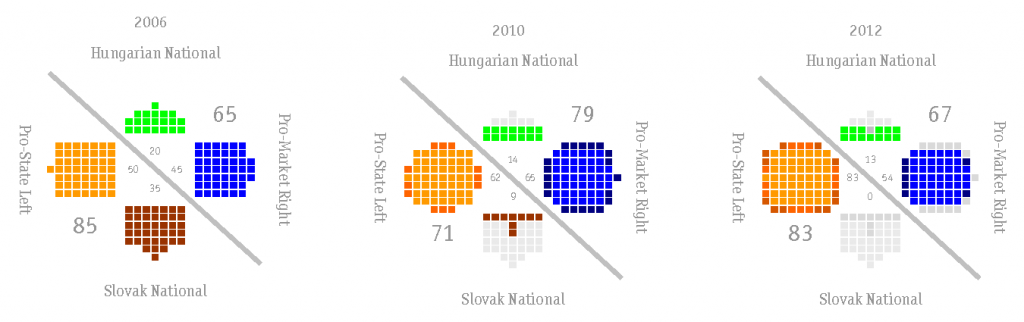

Dimension 2: Changes in relative bloc size. 2010 figure indicates lost seats in light grey and gained seats in deeper colors (deeper still for seats gained in 2012)

Fico gained an impressive number of seats in the 2012 election: 21 out of a 150 seat legislature. (The additional MPs in Fico’s party would, if they defected, immediately become the second largest party in parliament). The growth was the result both of transfer between sides (a swing of 12) and a nearly equal size transfer within his own side (a swing of 9 from SNS to Smer). This kind of victory creates new risks and rewards for Smer. On one hand, Smer must now govern alone and so unlike the 2006-2010 government, when the most viscerally-unpleasant corruption cases were those perpetrated by its coalition partners, it will not be able to avoid close identification with everything that goes wrong. If the right benefitted from disillusioned anti-corruption voters in 2010 and Fico got some of those back in 2012 when the right seemed to behave no better, then the flow of such voters in the next election will depend largely on how Smer conducts itself in government. The flip side of this focused responsibility is focused power. Smer can now govern alone, and it is worthwhile considering the consequences of a one-party Fico-led government

What happens now?

Robert Fico tests how the limits of one-party-rule in Slovakia (and one-man-rule in his own party)

When Robert Fico left the communist-successor Party of the Democratic Left in 1999 to form Smer, observers asked whether he was “a man to be trusted or feared”? (Indeed one of the authors of this piece, Tim Haughton, wrote on this exact question ten years ago). The question is even more relevant today. In the early 2000s, Fico offered Slovakia “new faces” and a “new direction.” In the 2012 campaign he offered the promise of certainty and stability. After a year and a half of a fractious coalition government, there will be some benefit to citizens and investors in a one-party Smer government, but what kind of certainty and stability can Fico offer?

One-party government is not without its risks. Slovakia’s political institutions have been protected to some extent in recent years by its tense coalitions, whose inability to agree have hampered their ability to deliver fundamental change (both good and bad). Because of Slovakia’s relatively open constitutional framework, a united parliamentary majority can impose significant changes not only on policy but on the institutional structure. For many in Slovakia any one party government would be source of worry even if its prime minister had not exhibited similarities to Vladimir Meciar, the three-time prime minister who came close to toppling Slovak’s democracy during the 1990s. Indeed there are some clear parallels between the two men, especially their central position to their parties’ identity and appeal and their willingness to the national card in political competition. Nor do some of the differences between the men offer much solace. Fico has demonstrated himself to be a more capable politician Meciar. Whereas Meciar oversaw the consistent decline of HZDS (from an admittedly high starting point), Fico has pushed Smer to more votes and more seats in every successive election.

But Smer’s progress also reflects Fico’s recognition of certain political limits and (unlike) Meciar, he has rarely pushed the boundaries too far. Chastened by a disappointing result in 2002, Fico spent much of the subsequent four years building his party’s organization and positioning Smer as the left-leaning alternative to the neoliberal policies of the second Dzurinda-led government. The party remains entirely dependent on Fico, but its organizational expansion has left it with a variety of internal factions and (it is said) financial sponsors that may begin to impose some of their own constraints. If they do not, Slovakia may now be able to fall back on other institutional structures that have strengthened since the Meciar era. Slovakia’s civil society has also demonstrated its ability to play a vibrant (if not always decisive) role. The anti-gorilla demonstrations may not have impacted much on the election result, but they show the willingness of many Slovaks to come out onto the streets if given provocation.

Although the Russian Pravda declared in a headline on Monday that the ‘good times may begin for Russia’ with this election because ‘it is difficult to find a more pro-Russian politician in all of the European Union’ than Robert Fico, it is worth recalling Fico’s press conference in the early hours of Sunday morning when it had become clear he would be the next prime minister. Fico was keen to stress his pro-European credentials. His last time in government began badly when he was roundly condemned by ideological allies in Europe for jumping into the coalition bed with the xenophobic and racist SNS leading to suspension from the Party of European Socialists. He will not want to be marginalized in Europe again. He knows that there are tough decisions ahead in Europe and that Slovakia’s future prosperity is dependent on Europe returning to healthy levels of growth. Past examples have revealed that Fico cares more about the give and take of domestic politics than anything else. He may thus simply ignore EU pressure, but he may have a harder time ignoring the supporters of his party whose livelihoods depend on the EU and wish to be left in peace to make their money.

The last time Fico held power he rode the wave of economic boom which his predecessors had done much to create. This time Fico takes power in an era of austerity and gloom. During the boom years some foreign investors were willing to turn a blind eye to the less than angelic behavior of members of Fico’s government, but with money now tighter, Fico will need to ensure that his government does not get embroiled in corruption scandals and that it stamps down on corruption at lower levels of government and administration. Admittedly many of the worst scandals affecting his government last time were those associated with ministers from Smer’s coalition partners SNS and HZDS, but Smer politicians were not immune. Fico knows that there are some in his ranks who have jumped on the Smer bandwagon hoping to feather their own nests. He must also be aware that if he does not succeed in controlling the greed of his party members, foreign investors may simply take their money elsewhere.

Maintaining support in government is intimately linked to how an administration deals with unexpected challenges and the economic context in which those decisions are made. If as Eurozone leaders are keen to stress, the European economy has turned the corner, Fico may benefit as Europe recovers from euro-related woes, but a glance at Greece indicates we might want to draw a different conclusion.

We have both spent long enough observing Slovak politics to expect the unexpected. Recent history offers us a guide, but as financial advisers would remind us past performance is only a guide to future outcomes. The only certainty is that to understand Slovak politics we need to understand the building blocs of party politics in Slovakia.

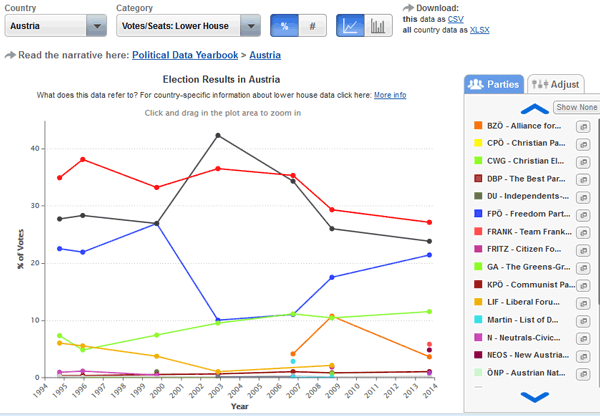

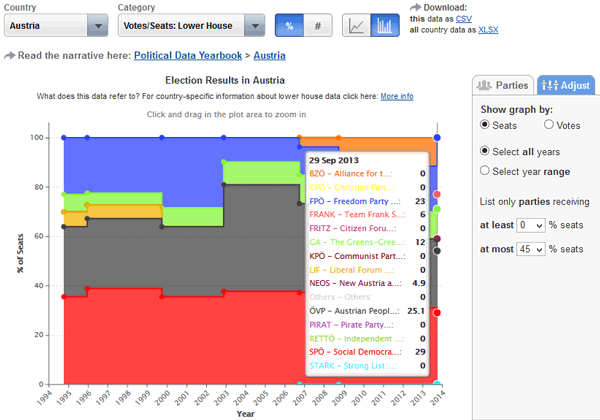

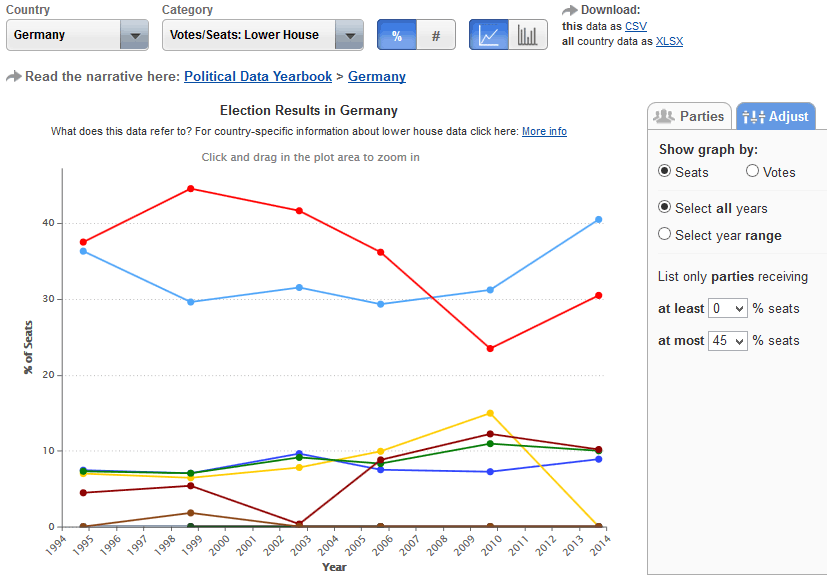

In button form the Austrian flag looks a lot like a “Do Not Enter” sign, but this election at least that did not apply for new parties (of course the thing I am most interested in these days). There was some significant volatility in Austria this year. In raw party terms, two new parties entered and one existing party left parliament. There was a minimum of 14.5% shift in votes and a 16% shift in seats (less than in the last election, for which my figures are 17% of votes and 27% of seats, but much more than Austria’s overall average during the post-WWII period.) The shift was of a different character, furthermore: whereas nearly all of Austria’s volatility has in the recent past been among parliamentary parties (Mainwaring’s intra-system volatility, Tucker and Powell’s Type A volatility), this year nearly half of the total volatility (6.2% of 14.5) was related to new entries and exits (extra-system or Type B). In the last election the extra-system volatility was nearly as high (5.9%) but it was outweighed by intra-system volatility (10.9%); in elections before 2008, extra system volatility was barely discernable (averaging only 1.3%).

In button form the Austrian flag looks a lot like a “Do Not Enter” sign, but this election at least that did not apply for new parties (of course the thing I am most interested in these days). There was some significant volatility in Austria this year. In raw party terms, two new parties entered and one existing party left parliament. There was a minimum of 14.5% shift in votes and a 16% shift in seats (less than in the last election, for which my figures are 17% of votes and 27% of seats, but much more than Austria’s overall average during the post-WWII period.) The shift was of a different character, furthermore: whereas nearly all of Austria’s volatility has in the recent past been among parliamentary parties (Mainwaring’s intra-system volatility, Tucker and Powell’s Type A volatility), this year nearly half of the total volatility (6.2% of 14.5) was related to new entries and exits (extra-system or Type B). In the last election the extra-system volatility was nearly as high (5.9%) but it was outweighed by intra-system volatility (10.9%); in elections before 2008, extra system volatility was barely discernable (averaging only 1.3%).

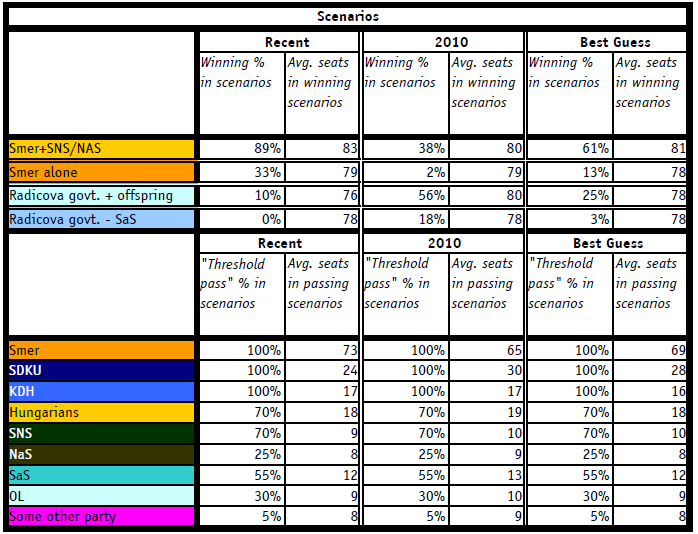

![ScreenClip [3]](http://www.pozorblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/ScreenClip-3.png)

![ScreenClip [4]](http://www.pozorblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/ScreenClip-4.png)

![ScreenClip [5]](http://www.pozorblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/ScreenClip-5.png)

![ScreenClip [2]](http://www.pozorblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/ScreenClip-2.png)

![ScreenClip [6]](http://www.pozorblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/ScreenClip-6.png)

Oscar Wilde once wrote that there is only one thing worse than being talked about and that is not being talked about. But in international politics that isn’t always the case. Slovakia was prominent in the coverage of the three most influential dailies in Europe on Wednesday: Le Monde, the Financial Times and the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Le Monde, for instance, bemoaned the political game being played in Slovakia, wondering in a linked article whether France’s AAA rating will survive the crisis. Sulik’s actions even caused ripples across the Atlantic where Slovakia was also the subject of articles in the New York Times and Washington Post.

Oscar Wilde once wrote that there is only one thing worse than being talked about and that is not being talked about. But in international politics that isn’t always the case. Slovakia was prominent in the coverage of the three most influential dailies in Europe on Wednesday: Le Monde, the Financial Times and the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Le Monde, for instance, bemoaned the political game being played in Slovakia, wondering in a linked article whether France’s AAA rating will survive the crisis. Sulik’s actions even caused ripples across the Atlantic where Slovakia was also the subject of articles in the New York Times and Washington Post.