In the eight previous posts in this series (and in this blog in general) I’ve used public opinion as the basic raw-material, but pollsters in Central Europe are quick to note that public opinion only talks about the “current” state of affairs and does not predict what people do once they enter the voting booth. They walk a fine line on this point, between irrelevance on one hand (if pollsters admit that polls do not predict elections, why should we pay attention to them?) and embarrassment on the other (when the “normal” 24% gap between polls and actual results causes people to notice that polls do not do a very good job of predicting elections). But the world is full of people who, like myself, who are uncomfortable with waiting for news and need some early indicators, at least, of how things will turn out (my wife has learned from my uncomfortable fidgeting when she says “I have news…” to include a spoiler like “and it’s not bad news, or at least not very bad news.” This inability to deal with uncertainty in the political world drives me (and perhaps a few other people) to use whatever resources are available to look for the best way to predict the future.

In the eight previous posts in this series (and in this blog in general) I’ve used public opinion as the basic raw-material, but pollsters in Central Europe are quick to note that public opinion only talks about the “current” state of affairs and does not predict what people do once they enter the voting booth. They walk a fine line on this point, between irrelevance on one hand (if pollsters admit that polls do not predict elections, why should we pay attention to them?) and embarrassment on the other (when the “normal” 24% gap between polls and actual results causes people to notice that polls do not do a very good job of predicting elections). But the world is full of people who, like myself, who are uncomfortable with waiting for news and need some early indicators, at least, of how things will turn out (my wife has learned from my uncomfortable fidgeting when she says “I have news…” to include a spoiler like “and it’s not bad news, or at least not very bad news.” This inability to deal with uncertainty in the political world drives me (and perhaps a few other people) to use whatever resources are available to look for the best way to predict the future.

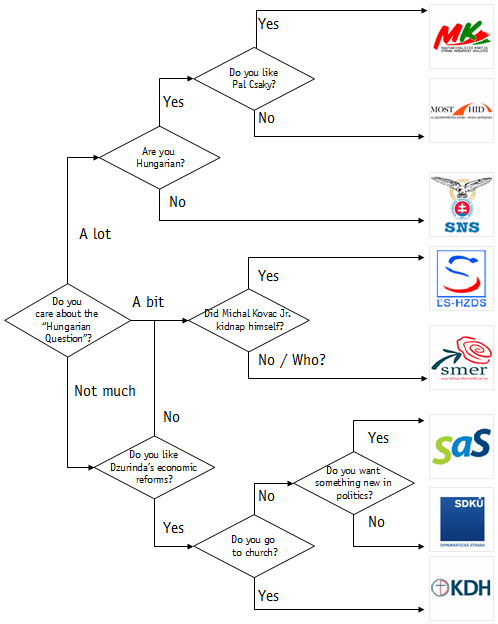

If polls aren’t it, then what is? In a previous post, I’ve looked at alternative quantitative measures for second-guessing the polls–committed voters, committed turnout, past trends–of which only the last seems to have much value (hence my rather cautious use of it). But the human brain is a marvelous thing, and the answers may not be easily found in the aggregation of statistics, however interesting they are in their own right. The secret is to find the right brain, or perhaps better said, to know which brain is the right one. In this we are limited to those who are willing to share the Slovak-election-related contents of their respective brains. Ideally we would have a significant number of people who have looked carefully at the available information and made an educated guess. How do we know if they have done so? Well without close attention to their study habits, the best way is to see whether they have something to gain if they are right (or something to lose if they are wrong). The discussion boards of SME, Pravda, HN and other news outlets are full of people willing to hazard a guess, but with few consequences for failure (especially since so many are anonymous). I am left, therefore with two main sources: those who stand to lose their reputations and those who stand to lose their money. Among those with reputations at stake, I do not include politicians, whose prognostications are never expected to be true (Pal Csaky predicts 10% for SMK) and so we are left with a small cadre of political scientists and pollsters who are willing to make their guesses public, and I will reference them here. In particular, I am grateful to Martin Slosiarik (this is only one of the many realms in which I owe him gratitude) for being willing to make his predictions public, and to make them narrow enough to be useful (though he cleverly shies away from one of the hardest questions).

Among those with money at stake, there is the growing field of those who bet on politics (actually has been extremely common in certain past eras) and a whole discourse has arisen about the predictivness of odds markets. In my own experience, these markets have done quite well in predicting obscure (to me) local races in the US. They are subject to manipulation, of course, but the more people become involved, the more difficult this becomes. Slovakia lacks a true odds market for politics. SME‘s “crystal ball” at http://zajtrajsie.sme.sk/ is a great first step, but the gains, as far as I can tell, are not particularly valuable (the S€ used in the betting cannot yet be used to buy beer) and so participants may make guesses without much genuine forethought, and since this is the first attempt, we won’t be able to tell until the results are in and the markets close (though this is something I will follow closely). The only other source we have are the people who make their money by encouraging others to bet. Bookmakers have a strong vested interest in setting the odds right and they can only do that if they make the right kind of predictions. So in addition to the political scientists and pollsters, it is interesting to look at what the bookies say.

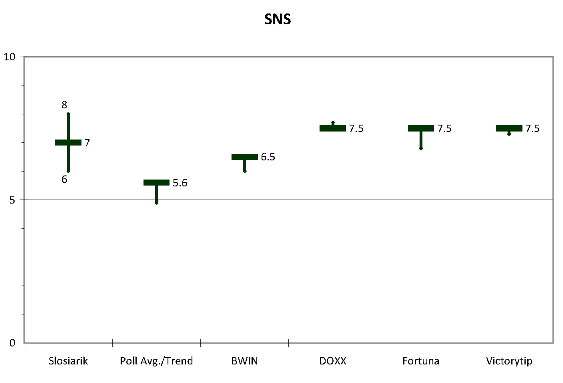

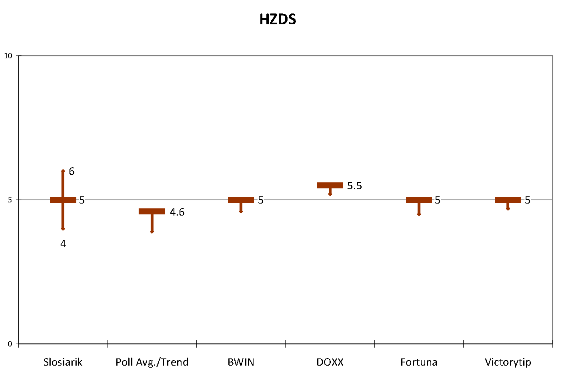

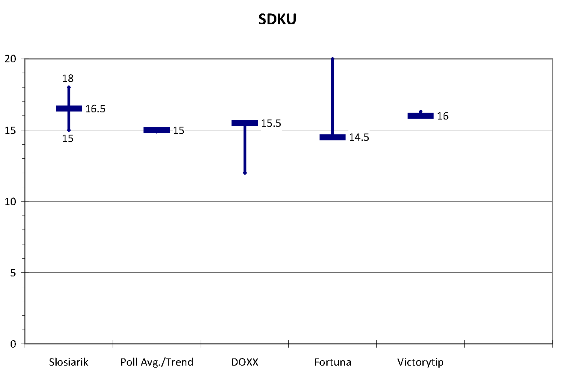

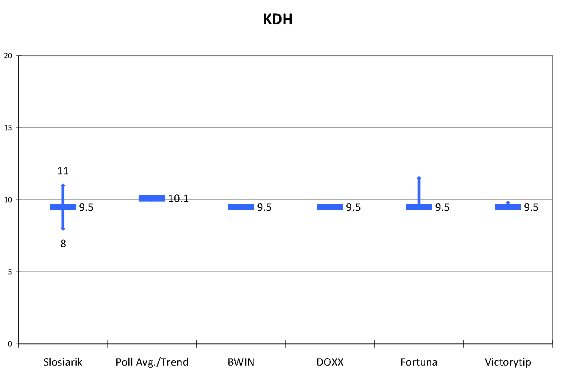

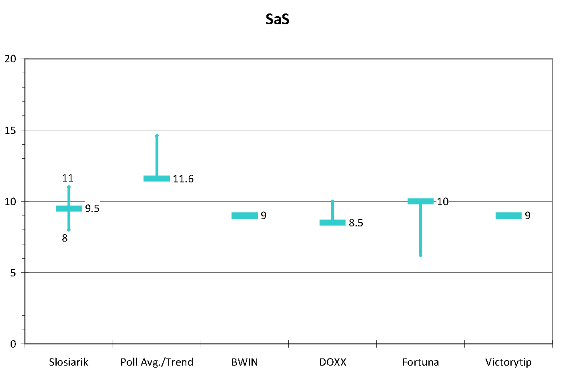

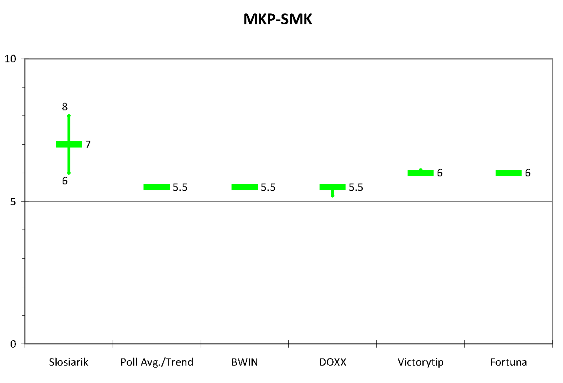

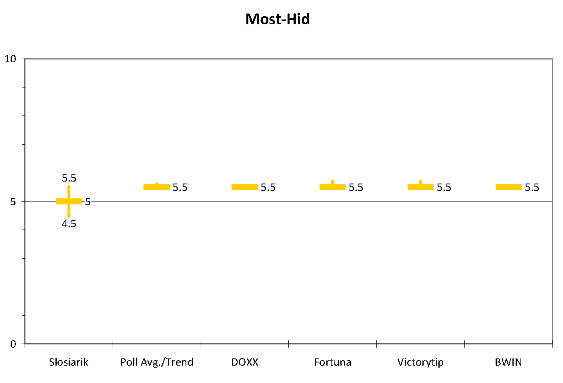

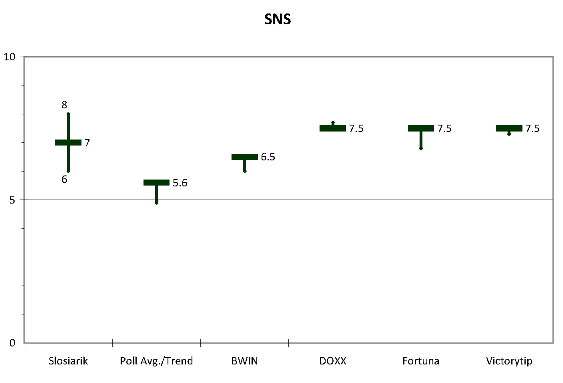

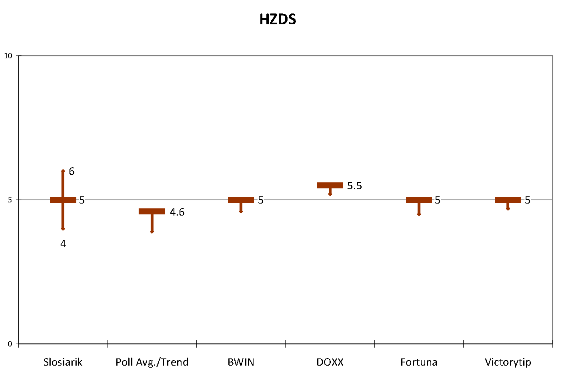

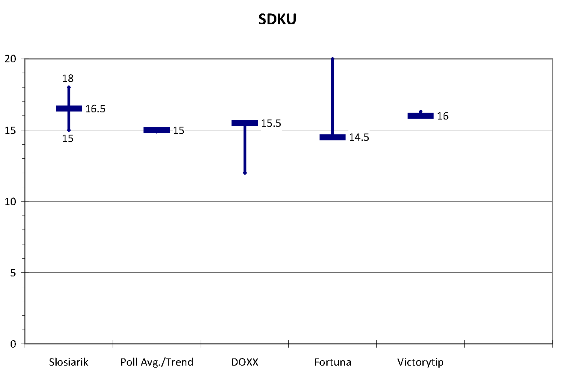

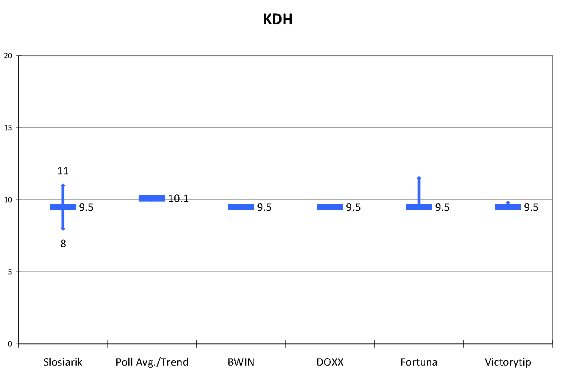

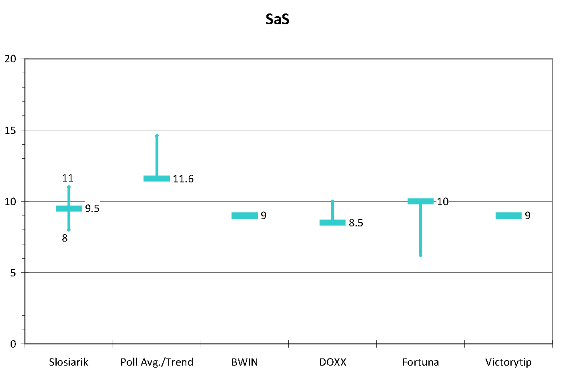

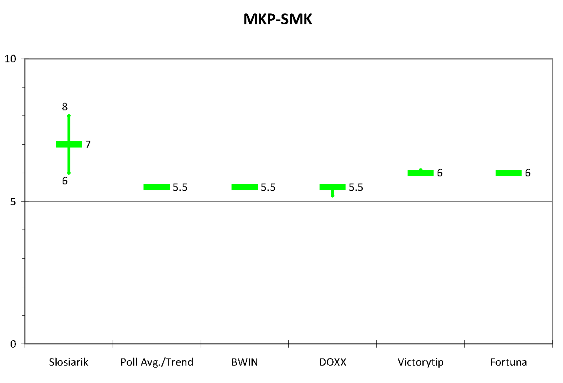

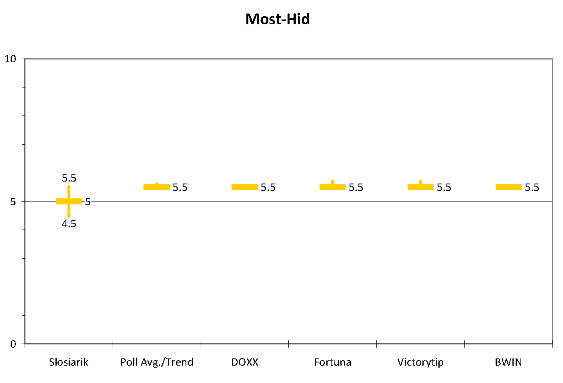

What I have therefore done is to create charts for each party that show the range predicted by Martin Slosiarik, a rough guess based on current poll average projected out two months based on current trends (my own rather superficial method, though one that did not work badly in the recent Czech election) and then the four bookmakers I have been able to find. In each case a dark bar represents the baseline: in Slosiarik’s case it is the center point of his predicted range, in my case it is the current poll average, and in the case of the bookmakers it is the inflection point of the bet itself (“Will SaS exceed 10% or fall short”). The small vertical line leading from it shows direction: in Slosiarik’s case the lines show his full range; in the case of the average poll results it shows the what the “two-month-out” method would predict; in the case of the bookmakers, it is a rough assessment of which side the odds favor. The longer the line, the more the odds favor a result in that direction (it is not a direct measure of what result the party will actually achieve).

What do we learn from these? For lack of a better method, let me go party by party as I usually do with poll results:

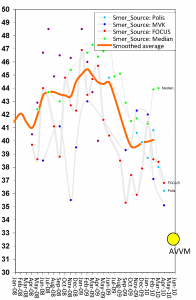

Smer. I will begin the analysis of Smer numbers in reverse order on the graph below, beginning with the four wagering firms (British firm bwin.com, and firms operating in Slovakia, Doxx, Fortuna and VictoryTip [unlike last election, Nike.sk and Tipos.sk do not appear to be participating].

Smer. I will begin the analysis of Smer numbers in reverse order on the graph below, beginning with the four wagering firms (British firm bwin.com, and firms operating in Slovakia, Doxx, Fortuna and VictoryTip [unlike last election, Nike.sk and Tipos.sk do not appear to be participating].

Betting odds can be hard to compare because the bets of this type are intrinsically binary and must begin from a particular baseline. In the case of Smer, each of the four begins from a different baseline, though these are relatively close together, spanning a narrow range between 32.0 and 33.5. These baselines appear in these cases to reflect the odds firm’s baseline guess, and the odds then suggest its subsequent adjustment. For Bwin and Doxx the odds were even at last check, but both Fortuna and VictoryTip put slightly shorter odds on Smer receiving more than their respective 32.5 and 33 suggesting an outcome slightly above 33. Average these together and you get an outcome of about 33% predicted by the odds markets as of 8 June. This is not far from the 34.8 minus 1.4 = 33.4 suggested by the (two-month-out”) poll prediction. Interestingly, however, it is rather higher than Slosiarik’s 30-33 range or the 30.5/30.6 prediction I derive from two separate but highly consistent SME odds markets (http://zajtrajsie.sme.sk/stavka/pridajstavku/447 and http://zajtrajsie.sme.sk/stavka/pridajstavku/520). Which of these is more accurate is impossible to say at the moment. SME readers tend to be somewhat more free market oriented than others and this may represent a bit of wishful thinking. Slosiarik, on the other hand, knows these numbers inside and out and and seems convinced of the softness of Smer support (he may well be right, but we won’t know for 4 more days).

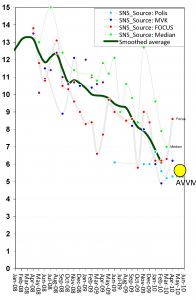

SNS. For SNS the baseline measures of three of the four betting firms is the same–7.5 while the fourth is lower at 6.5. All but one suggest a slight downward trend with an implied average of around 7.0. This is also the median of Slosiarik’s 6-8 range. It is interesting that for this party–the betting and expert models are most out of sync with the average polling results, which are under 6 or the trend, which would point the party even lower. This may be because these experts believe in the (not insignificant) effect of recent Hungarian policy decisions and/or believe that some Slovaks may be hiding their vote for a party that says publicly what some people think privately but might not be willing to admit. It is difficult for me to disagree with the experts in order to engage in some wishful thinking of my own.

SNS. For SNS the baseline measures of three of the four betting firms is the same–7.5 while the fourth is lower at 6.5. All but one suggest a slight downward trend with an implied average of around 7.0. This is also the median of Slosiarik’s 6-8 range. It is interesting that for this party–the betting and expert models are most out of sync with the average polling results, which are under 6 or the trend, which would point the party even lower. This may be because these experts believe in the (not insignificant) effect of recent Hungarian policy decisions and/or believe that some Slovaks may be hiding their vote for a party that says publicly what some people think privately but might not be willing to admit. It is difficult for me to disagree with the experts in order to engage in some wishful thinking of my own.

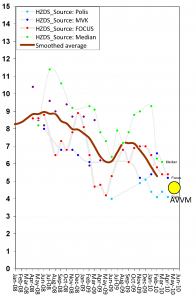

HZDS. HZDS is even more consistent than Smer or SNS. Only one betting firm even put HZDS’s baseline above the magical 5% threshold and that one, like all the others, put shorter odds on the party falling below the baseline, which in three out of the four cases means below the threshold for entry into parliament. Likewise Slosiarik puts HZDS in a 4-6 range that sets its median at 5%, though he carefully does not make any predictions about whether it will be slightly above or slightly below. The opinion polls here weigh in on the negative, both in terms of absolute numbers and two-months-out trend which puts it closer to 4 than to 5. (The SME odds markets also give HZDS a less than even chance of returning to parliament: 42.8:57.2. (http://zajtrajsie.sme.sk/stavka/pridajstavku/87)

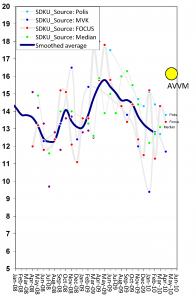

SDKU. SDKU has a relatively narrow range of baselines but rather broader range of odds spreads (even though one of the firms, Bwin, does not include the party among its range of bets. The range hovers between 14.5 and 16. Public opinion polls put the party at 15 with no discernible trend while Slosiarik puts it higher, on the grounds that it may pick up some voters who at the last moment decide that they are not comfortable voting for SaS (This may be the grounds for Fortuna’s quite short odds on the party receiving more than the baseline). Still, even this does not change the range particularly.

SDKU. SDKU has a relatively narrow range of baselines but rather broader range of odds spreads (even though one of the firms, Bwin, does not include the party among its range of bets. The range hovers between 14.5 and 16. Public opinion polls put the party at 15 with no discernible trend while Slosiarik puts it higher, on the grounds that it may pick up some voters who at the last moment decide that they are not comfortable voting for SaS (This may be the grounds for Fortuna’s quite short odds on the party receiving more than the baseline). Still, even this does not change the range particularly.

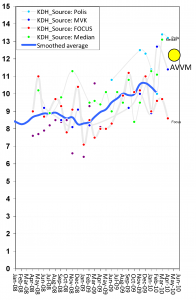

KDH. KDH produces very consistent results: 9.5 or slightly above. This is true whether you look at the four betting firms, all of which chose the same baseline, or at Slosiarik’s 8-11 range or at the current polls which put the party at 10%. This is, not coincidentally also the party’s basic result for nearly every parliamentary election in which it has run independently since 1990, though that itself is rather odd since the party has changed, its voters have changed, its leaders have changed, the country has changed and yet KDH manages the same old 10% every time.

KDH. KDH produces very consistent results: 9.5 or slightly above. This is true whether you look at the four betting firms, all of which chose the same baseline, or at Slosiarik’s 8-11 range or at the current polls which put the party at 10%. This is, not coincidentally also the party’s basic result for nearly every parliamentary election in which it has run independently since 1990, though that itself is rather odd since the party has changed, its voters have changed, its leaders have changed, the country has changed and yet KDH manages the same old 10% every time.

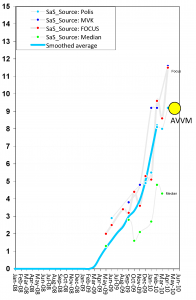

SaS. SaS shows a relatively narrow range of baselines–from 8.5 to 10.0 with odds pointing in opposite directions (the lowest baseline, Doxx giving short odds for a higher score and the highest baseline, Fortuna, giving short odds for a lower score. They meet somewhere around the middle–around the 9.5 that is in the middle of Slosiarik’s range. As with SNS, SaS odds and experts differ from the polling average for the party and its trend, perhaps reflecting insider knowledge (or the belief therein) that new parties poll high and then end up lower (as I’ve discussed above, this was true for almost every new party to enter Slovakia’s system: ZRS, SOP, ANO, Smer, HZD, SF) but, interestingly, it was not true for the Czech VV which in many ways is quite similar to SaS or for the rather different but equally new TOP09. I tend to agree with the experts in pegging SaS down a few points but the Czech case gives me just a bit of pause.

SaS. SaS shows a relatively narrow range of baselines–from 8.5 to 10.0 with odds pointing in opposite directions (the lowest baseline, Doxx giving short odds for a higher score and the highest baseline, Fortuna, giving short odds for a lower score. They meet somewhere around the middle–around the 9.5 that is in the middle of Slosiarik’s range. As with SNS, SaS odds and experts differ from the polling average for the party and its trend, perhaps reflecting insider knowledge (or the belief therein) that new parties poll high and then end up lower (as I’ve discussed above, this was true for almost every new party to enter Slovakia’s system: ZRS, SOP, ANO, Smer, HZD, SF) but, interestingly, it was not true for the Czech VV which in many ways is quite similar to SaS or for the rather different but equally new TOP09. I tend to agree with the experts in pegging SaS down a few points but the Czech case gives me just a bit of pause.

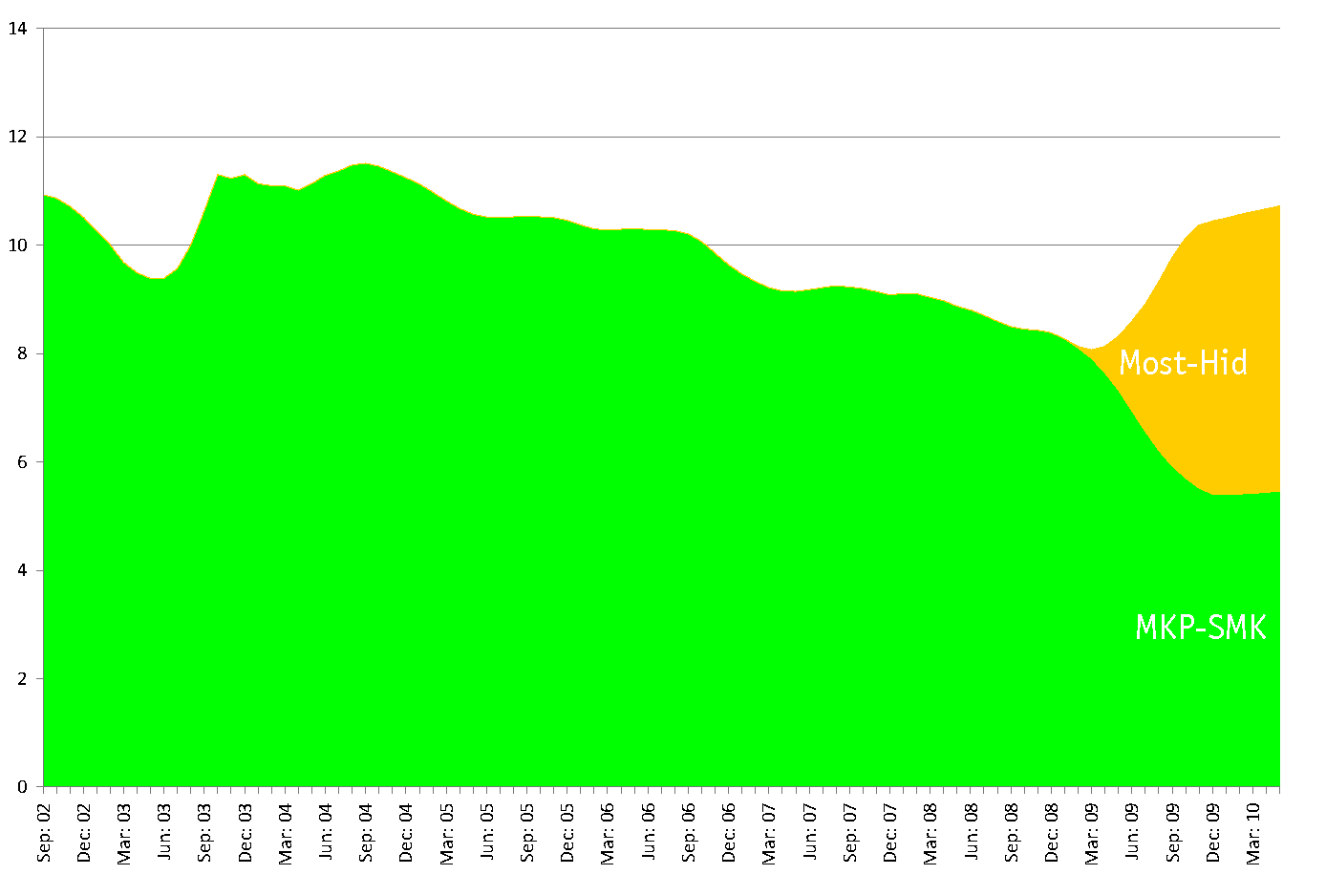

MKP-SMK. MKP has an extremely evenset of baselines–between 5.5 and 6.0 with only the barest hint of a trend in one or two. This is identical to the public opinion average. Both are lower than Slosiarik’s range of 6 to 8. The betting firms may just be playing it safe here since there is really no way of telling here. Slosiarik clearly expects voters to fall back to MKP from Most (just as he seems to expect them to fall back to SDKU from SaS. As above, there is good reason to agree but past precedent may not always dictate current action. This is the question I will be most curious to see answered on election day.

MKP-SMK. MKP has an extremely evenset of baselines–between 5.5 and 6.0 with only the barest hint of a trend in one or two. This is identical to the public opinion average. Both are lower than Slosiarik’s range of 6 to 8. The betting firms may just be playing it safe here since there is really no way of telling here. Slosiarik clearly expects voters to fall back to MKP from Most (just as he seems to expect them to fall back to SDKU from SaS. As above, there is good reason to agree but past precedent may not always dictate current action. This is the question I will be most curious to see answered on election day.

Most-Hid. Surprisingly to me, Most-Hid has the most consistent set of baselines–all at 5.5–and odds (nothing shorter than 1.75 or longer than 1.85). The reason that this is surprising is that Most-Hid has perhaps the most unpredictable electorate. We really have little basis for judging whether they will switch back to the tried and true MKP at the last minute, as Slosiarik clearly thinks many will. He says Most-Hid will be “very close to 5%” but if you look at his prediction for MKP-SMK and assume that the total electorate for Hungarian parties is less than 12%, his actual prediction seems to be slightly lower than 50-50 that Most-Hid will make it into parliament, something that he probably avoided saying directly lest it produce the headline “FOCUS expert rules out Most-Hid”

Most-Hid. Surprisingly to me, Most-Hid has the most consistent set of baselines–all at 5.5–and odds (nothing shorter than 1.75 or longer than 1.85). The reason that this is surprising is that Most-Hid has perhaps the most unpredictable electorate. We really have little basis for judging whether they will switch back to the tried and true MKP at the last minute, as Slosiarik clearly thinks many will. He says Most-Hid will be “very close to 5%” but if you look at his prediction for MKP-SMK and assume that the total electorate for Hungarian parties is less than 12%, his actual prediction seems to be slightly lower than 50-50 that Most-Hid will make it into parliament, something that he probably avoided saying directly lest it produce the headline “FOCUS expert rules out Most-Hid”

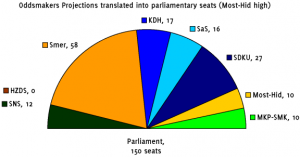

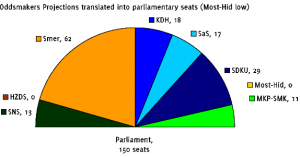

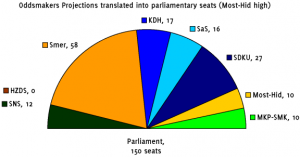

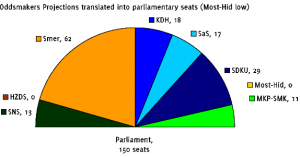

So what happens when we put all of these together? The table below gives a rough estimate of the median point of the odds-makers. (There is no simple way to calculate these because there is no pure way to factor in what the odds mean for preferences. Very short odds on a party that has a baseline of 5.0 might mean that the pollster is absolutely certain that the party will finish with 4.9 or that it will finish with 2.0. Of course all things being equal the shorter or longer odds are likely to be somehow proportional to the distance from the baseline since that distance is the most probable basis for certainty. If there’s anybody in the odds business who can set me straight, I’d very much appreciate it.)

| Party |

Odds Markets |

Slosiarik |

| Percentage |

Seats |

Percentage |

Seats |

| Model |

Minus

Most-Hid |

Model |

Minus

Most-Hid |

Minus

HZDS |

Minus

Most-Hid

and HZDS |

| Smer |

33.0 |

58 |

62 |

31.5 |

52 |

55 |

55 |

59 |

| SNS |

7.0 |

12 |

13 |

7.0 |

12 |

12 |

12 |

13 |

| HZDS |

4.8 |

0 |

0 |

5.0 |

8 |

9 |

0 |

0 |

| SDKU |

15.5 |

27 |

29 |

16.5 |

27 |

29 |

29 |

31 |

| KDH |

9.8 |

16 |

17 |

9.5 |

11 |

12 |

12 |

13 |

| SaS |

9.0 |

10 |

11 |

9.5 |

16 |

16 |

17 |

17 |

| MK |

5.5 |

17 |

18 |

7.0 |

8 |

0 |

9 |

0 |

| Most |

5.5 |

10 |

|

5.0 |

16 |

17 |

16 |

17 |

| Current Coalition |

44.8 |

70 |

75 |

43.5 |

72 |

76 |

67 |

72 |

| Current Opposition |

45.3 |

80 |

75 |

47.5 |

78 |

74 |

83 |

78 |

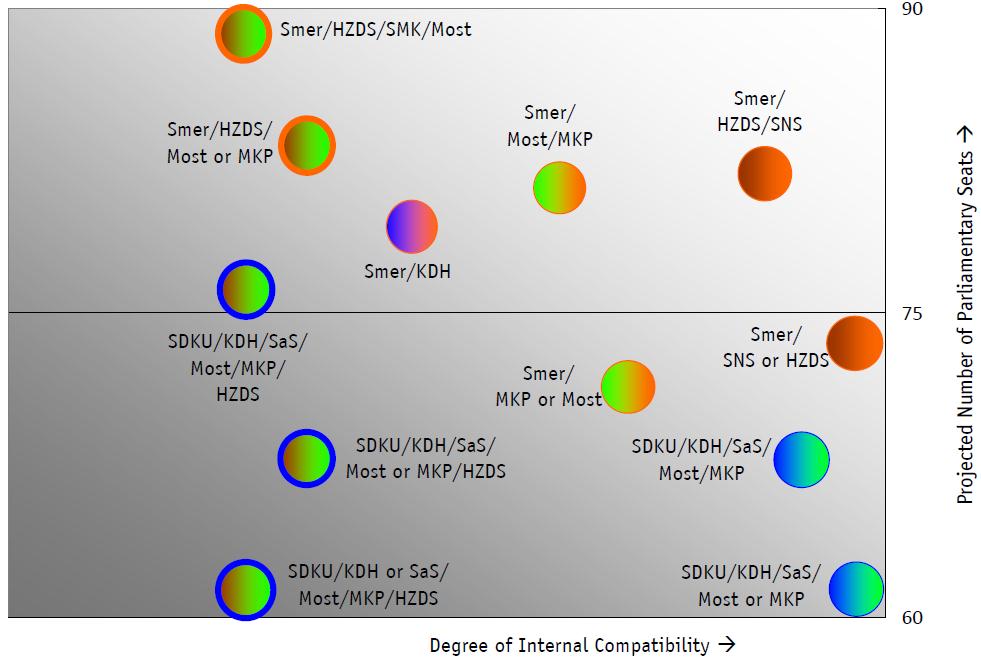

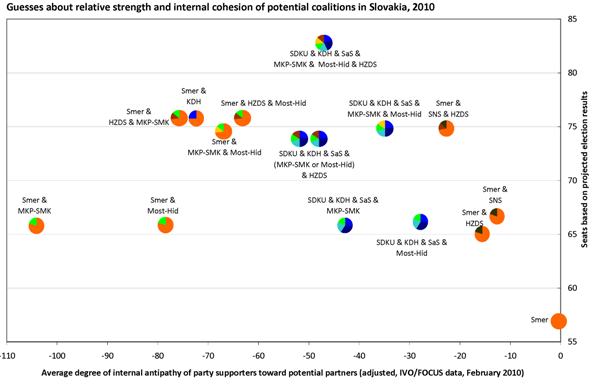

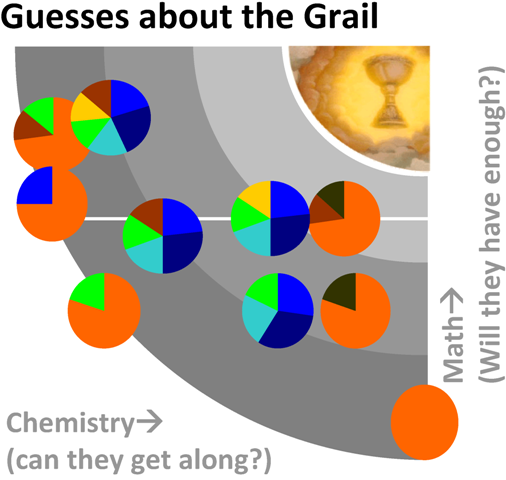

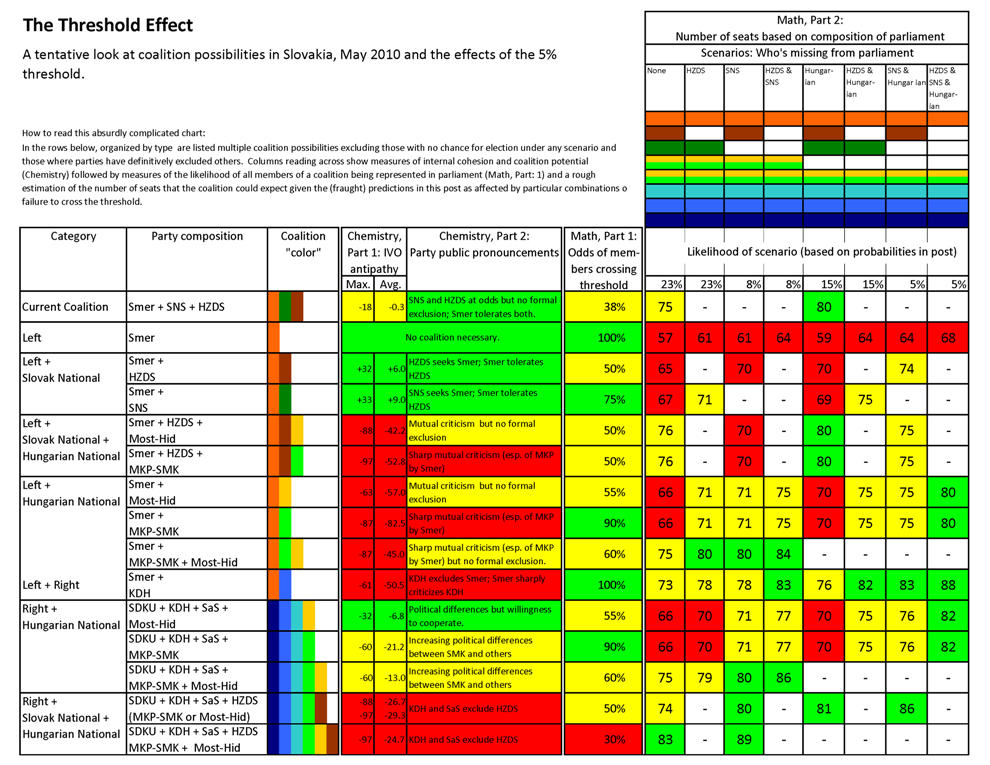

The results are not particularly auspicious for the current coalition as it depends on two narrow chances: HZDS in parliament and Most-Hid out. Without both of these conditions–the odds makers narrowly predict HZDS’s exclusion–the best Smer could hope for (according to the oddsakers, at least) would be for the failure of Most-Hid which in this case would produce a 75-75 split. Otherwise, Smer will need to reach across the aisle or face the possibility of an opposition coalition. Slosiarik’s slightly different numbers produce the same conclusion. Only the presence of HZDS and absence of Most-Hid produces a coalition majority in his model, and then only a very narrow one.

Indeed the striking piece of information here, beyond the importance of thresholds to which I’ve alluded on numerous occasions, is the narrowness of governmental margins. Slovakia may be entering a period that looks a bit like recent Czech political history with fragile or even minority governments (especially if MKP-SMK were to become untouchable”).

Of course all this depends on whether the odds makers and experts know what they are talking about.

P.S. Want to bet on this? You can figure out from the above where the best odds are. Here are the oddsmakers:

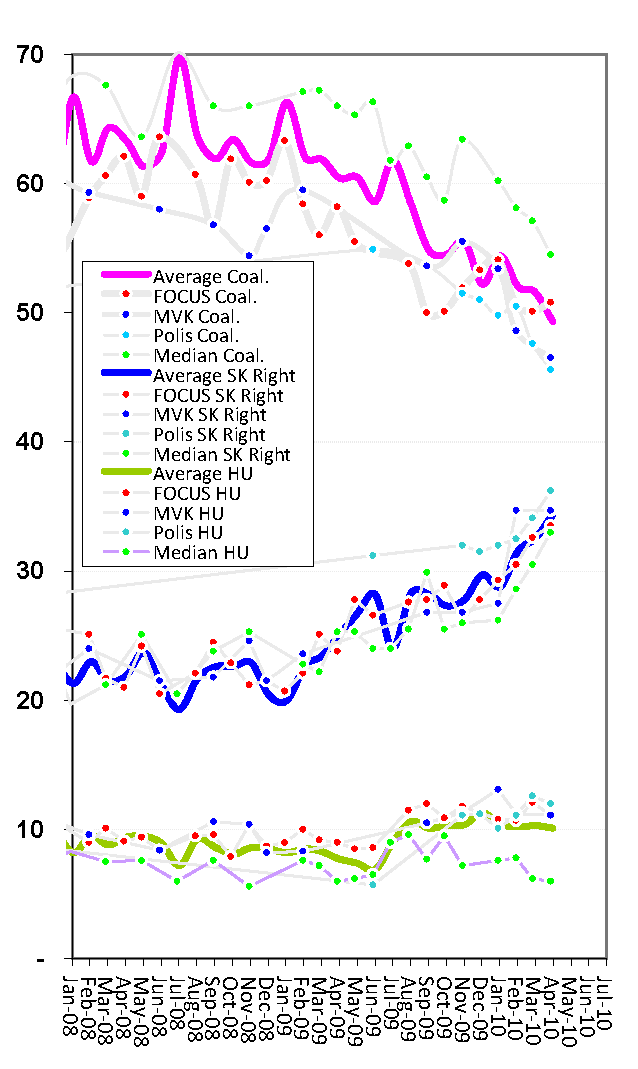

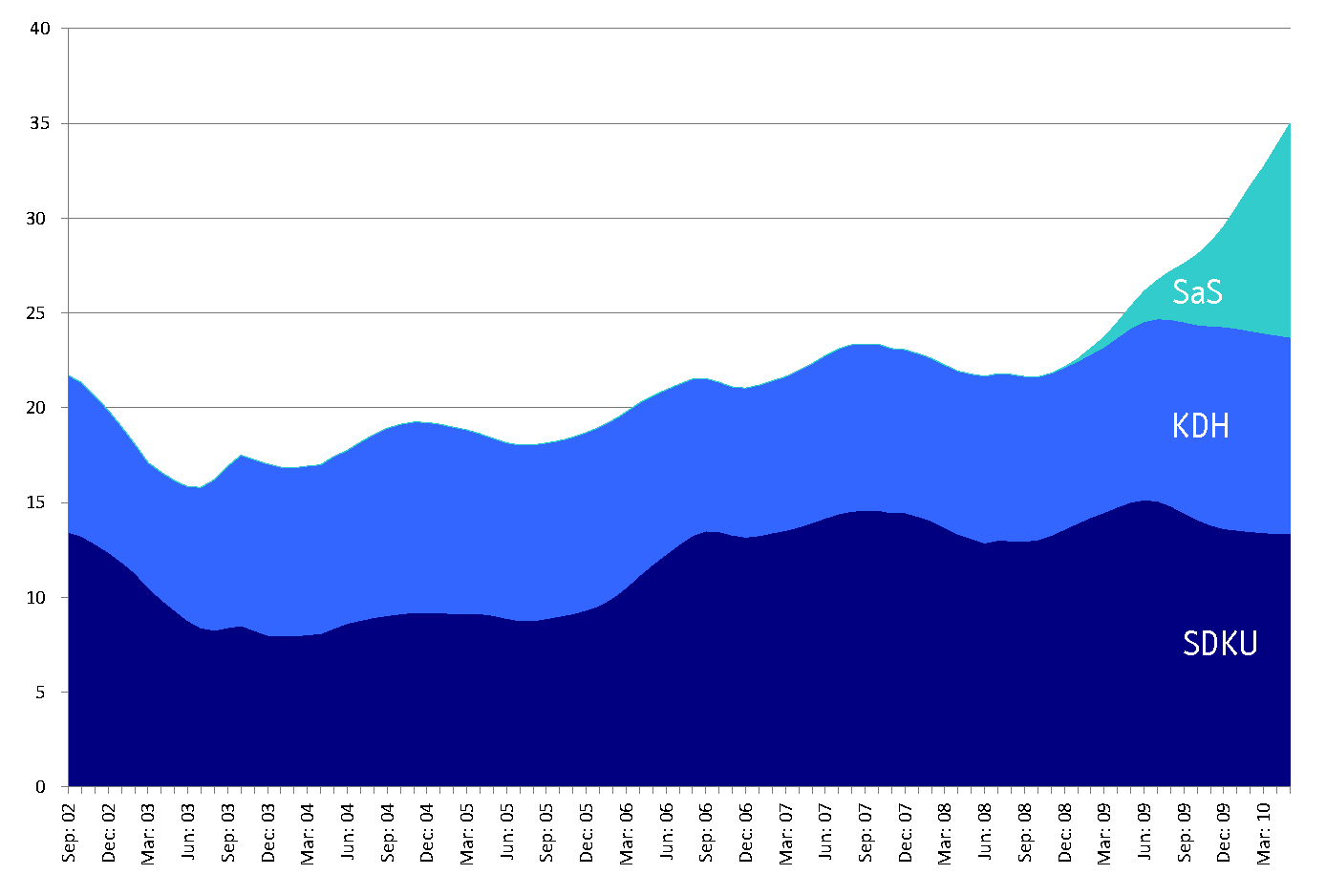

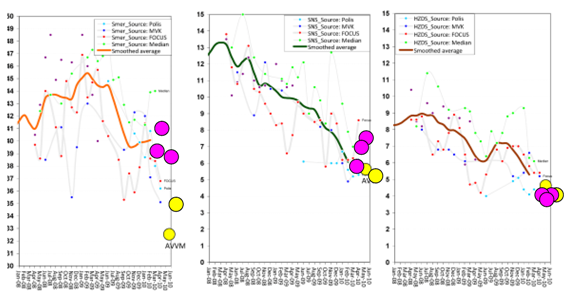

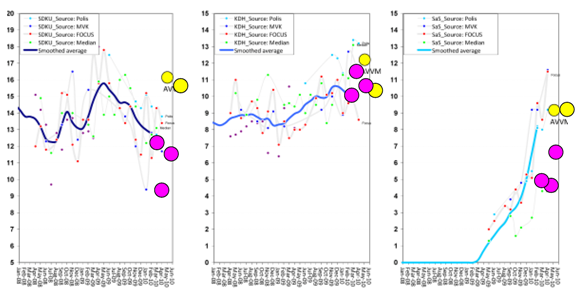

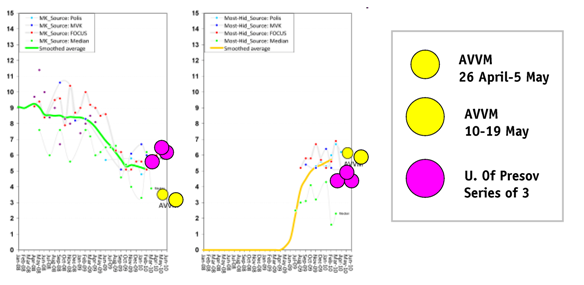

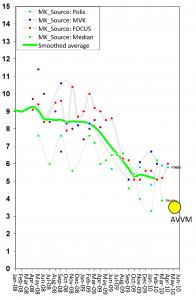

https://www.bwin.com/politicsB

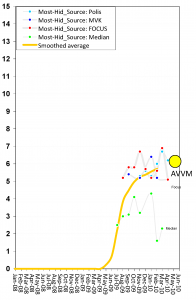

I love polling results and I am always surprised and unhappy when they are abused. Recent articles in SME and Pravda put needless stress on these results by, on the one hand, treating them as unique and absolute indicators of a party’s success or failure (at least until the next one comes out) and, on the other hand, lumping them together into time series regardless of their origin or methodology. Toward this end, I propose that we fix this by, on the one hand, treating each poll as a unique series which is to be compared to other series, and, on the other hand, when we do lump them together into time series, we smooth them out and look less at individual polls and more at overall trends. I’ve tried to do both of those things here with some overall coalition/opposition graphs that, I think, speak for themselves in various ways (though that probably won’t stop me from trying to speak for them at some future point.

I love polling results and I am always surprised and unhappy when they are abused. Recent articles in SME and Pravda put needless stress on these results by, on the one hand, treating them as unique and absolute indicators of a party’s success or failure (at least until the next one comes out) and, on the other hand, lumping them together into time series regardless of their origin or methodology. Toward this end, I propose that we fix this by, on the one hand, treating each poll as a unique series which is to be compared to other series, and, on the other hand, when we do lump them together into time series, we smooth them out and look less at individual polls and more at overall trends. I’ve tried to do both of those things here with some overall coalition/opposition graphs that, I think, speak for themselves in various ways (though that probably won’t stop me from trying to speak for them at some future point.

There is an old saying that “figures don’t lie, but liars do figure” (which I’m sure has some equivalent in almost every language) and there is a wonderful book written in 1954 provocatively entitled “

There is an old saying that “figures don’t lie, but liars do figure” (which I’m sure has some equivalent in almost every language) and there is a wonderful book written in 1954 provocatively entitled “

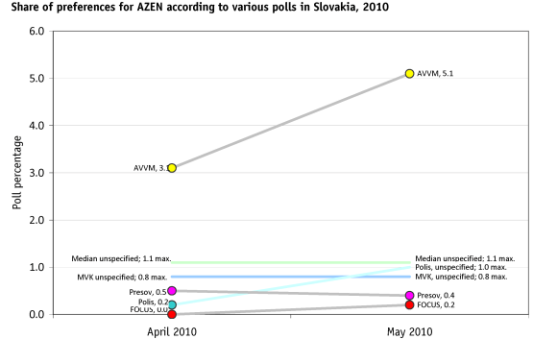

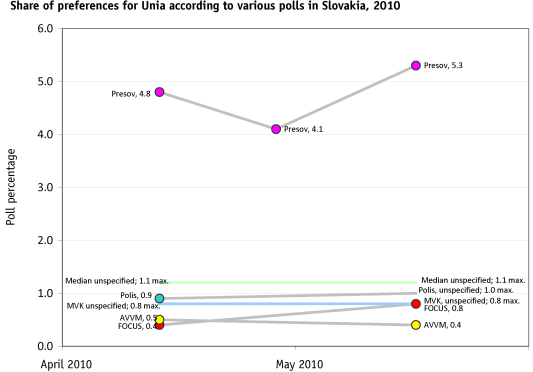

If AVVM hasn’t figured out some way to control for this then either a) its polls do not deserved to be published anywhere or b) I will be able to win a significant share of Slovakia’s vote simply by registering a new party under the name “Aardvark Alliance”

If AVVM hasn’t figured out some way to control for this then either a) its polls do not deserved to be published anywhere or b) I will be able to win a significant share of Slovakia’s vote simply by registering a new party under the name “Aardvark Alliance”

Thanks to Michaela Stankova of the

Thanks to Michaela Stankova of the

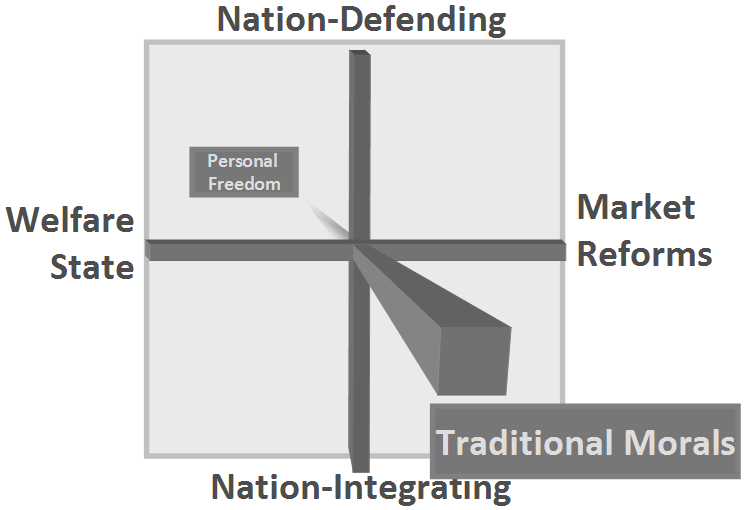

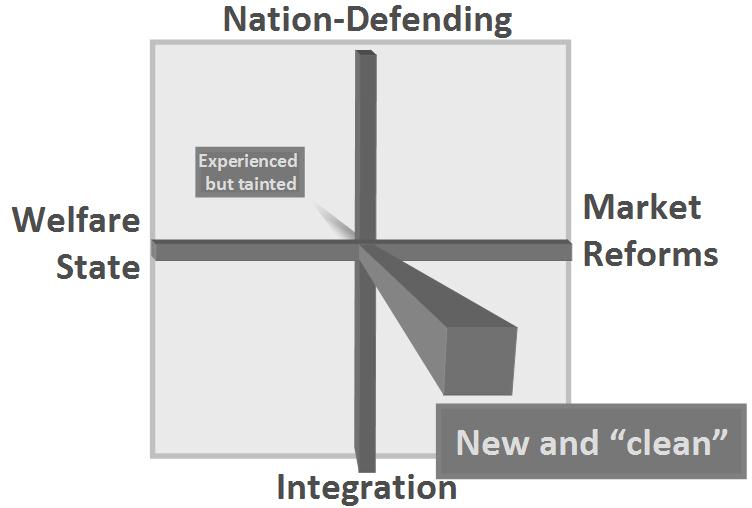

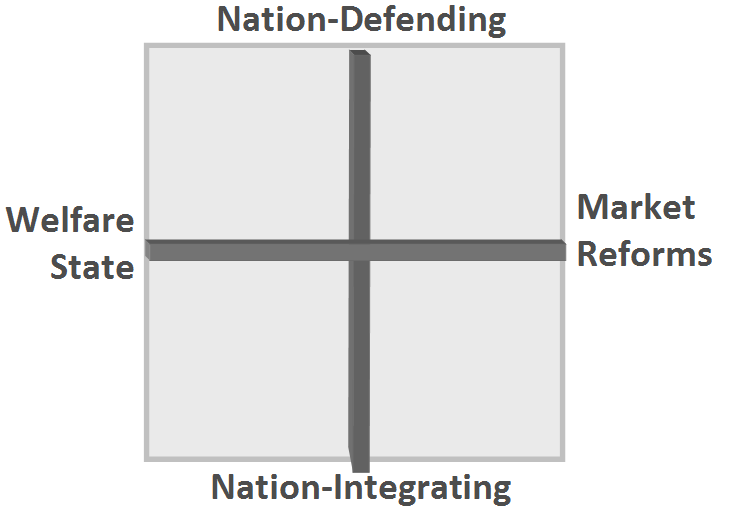

This gets a bit complicated, of course, because “nation integrating” means, “Slovak nation defending” and its rival pole is not so much “Slovak nation integrating” as “Hungarian nation defending” but I simplify it here because the main area in which Hungarian parties and Slovak parties agree on this side of the axis is the need to integrate Slovakia into European structures. Regardless of their labels, the important question is the degree to which these axes are independent of one another or somehow aligned so that positions on one are closely related to positions on the other. This is an open question in changing circumstances.

This gets a bit complicated, of course, because “nation integrating” means, “Slovak nation defending” and its rival pole is not so much “Slovak nation integrating” as “Hungarian nation defending” but I simplify it here because the main area in which Hungarian parties and Slovak parties agree on this side of the axis is the need to integrate Slovakia into European structures. Regardless of their labels, the important question is the degree to which these axes are independent of one another or somehow aligned so that positions on one are closely related to positions on the other. This is an open question in changing circumstances.