The beginning of a semester often means the end of active posting, and such was the case during the winter and spring of 2011–though indeed I took the absence of activity to rather absurd lengths–but the semester is now over and so I can again begin to post from time to time. Although much happened in Slovakia and the Czech Republic in the last 4 months: coalition crises and fear of government collapse in both countries, not that much has happened in terms of public opinion (which—since others are much better positioned to handle the day-to-day political dynamic—is the main focus of my posts).

The beginning of a semester often means the end of active posting, and such was the case during the winter and spring of 2011–though indeed I took the absence of activity to rather absurd lengths–but the semester is now over and so I can again begin to post from time to time. Although much happened in Slovakia and the Czech Republic in the last 4 months: coalition crises and fear of government collapse in both countries, not that much has happened in terms of public opinion (which—since others are much better positioned to handle the day-to-day political dynamic—is the main focus of my posts).

New season, same garden

Almost one year after the election, the polls suggest that elections would return a parliament relatively similar to the one Slovakia has now. There are some shifts in relative proportions, and though these are not overwhelming, they deserve attention. I will begin with the newly “locked-out” cases, then address the newly “locked-in” and finally take a brief look at the long-standing parties in the system (my colleague Tim-Haughton and I have taken to calling these “perennials” to describe their ability to withstand difficulties, as opposed to annuals that die each year and whose “type” survives only by reseeding).

The graphs are in the dashboard: http://www.pozorblog.com/slovakia-public-opinion-dashboard/.

As often happens in Slovakia, electoral periods lock in an equilibrium for a period of time, particularly with reference to the 5% electoral threshold. Parties that fall below the 5% threshold in elections tend to stay below (no party has returned to parliament without a coalition once it has fallen short of the threshold, and KSS is the only example of a party that has entered parliament after previously campaigning and falling short. Indeed with the exception of KSS, SZS in the early 1990’s and HZD for 4 months in the summer of 2004, I can find no party that has even broken received 5% in opinion polls after previously having fallen short). The same phenomenon works in the opposite direction—parties, once elected, tend to stay above the 5% threshold for a time—though the floor is far less stable than the ceiling.

Perennials in decline.

Two parties fell below the threshold in 2010 and show no sighs of being able to return at any time in the near future:

HZDS has maintained its steady decline after the election. In some polls it now is no longer even listed. This is remarkable feat for a party that once won a near majority of parliamentary seats—sustained, gradual decline over 7 election periods. It is a testament both to the ability of its party leader to hold the party together and to what happens when there is only a party leader to hold a party together.

HZDS has maintained its steady decline after the election. In some polls it now is no longer even listed. This is remarkable feat for a party that once won a near majority of parliamentary seats—sustained, gradual decline over 7 election periods. It is a testament both to the ability of its party leader to hold the party together and to what happens when there is only a party leader to hold a party together.

SMK is a fascinating case. The party that dominated the Hungarian electorate for 10 years (and 10 years previously as an electoral coalition) has fallen to extremely low levels, suggesting an overall shift to Most-Hid. Of course it doesn’t hurt that Most-Hid is run by the leader who led SMK during its dominant period and so in many ways this is merely a reshuffling of the same cards.

SMK is a fascinating case. The party that dominated the Hungarian electorate for 10 years (and 10 years previously as an electoral coalition) has fallen to extremely low levels, suggesting an overall shift to Most-Hid. Of course it doesn’t hurt that Most-Hid is run by the leader who led SMK during its dominant period and so in many ways this is merely a reshuffling of the same cards.

Annuals in bloom, but for how long?

The long-term exclusion of sagging older parties is far more likely than the long-term success of at least some new ones. The asymmetry appears to affect SaS more than Most-Hid.

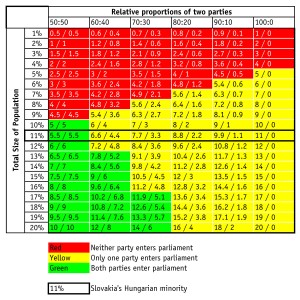

Most-Hid has the advantage of a relatively captive audience. Hungarians in Slovakia have not typically voted for non-Hungarian parties, and so the decline of SMK and the rise of Most-Hid are nearly isometric. Recovery by SMK might simply reverse the fortunes of these two parties or it might—if not too much blood has been shed or if enough time has passed since the bloodshed—lead to an electoral coalition of the sort that Hungarian parties in Slovakia used profitably for several election cycles in the 1990’s. It would appear that Slovakia’s Hungarian population may be just a bit too big for only one party but too small for two fairly (but not perfectly) matched competitive parties). The attached, rather ad hoc table helps to define the dilemma.

Most-Hid has the advantage of a relatively captive audience. Hungarians in Slovakia have not typically voted for non-Hungarian parties, and so the decline of SMK and the rise of Most-Hid are nearly isometric. Recovery by SMK might simply reverse the fortunes of these two parties or it might—if not too much blood has been shed or if enough time has passed since the bloodshed—lead to an electoral coalition of the sort that Hungarian parties in Slovakia used profitably for several election cycles in the 1990’s. It would appear that Slovakia’s Hungarian population may be just a bit too big for only one party but too small for two fairly (but not perfectly) matched competitive parties). The attached, rather ad hoc table helps to define the dilemma.

In countries where the population of a particularly captive (political scientists would use the world “encapsulated”) group is the leaders in the system have relatively little freedom to split without endangering the representation of the entire population: if the encapsulated population is, for example, 7%, then even a gain of 30% of the population by an upstart party will push both old and new parties below a 5% parliamentary threshold. If, on the other hand, the encapsulated population is more than twice the threshold, then even a nearly equal split will at worst reduce the representation of the group in half but will not eliminate it entirely. If the encapsulated population is relatively large, say 17%, then even a 70%-30% split will allow both parties over the 5% threshold and there is little cost to the split. Slovakia is right in the middle of these cases. It’s 11% Hungarian population made a split within the SMK thinkable—it would likely not result in the elimination of both parties from parliament—but not safe, since anything less than a near perfect split would (and did) knock one party from parliament. What happens with SMK and Most-Hid will likely depend on two factors: 1) the degree to which Most-Hid can capture the remaining share of the Hungarian vote (if it captures all of it, there is no incentive to change), and 2) the degree to which Hungarian leaders seek partisan advantage (one party triumphing over another even at the expense of a smaller Hungarian delegation) or ethnic advantage (one party accepting the other as a partner to maximize overall votes at the expense of party dominance).

SaS has seen a slight post-election decline after a rapid pre-election rise. We have seen this pattern before in many similar parties—ZRS, SOP, ANO and Smer—but we have also seen two different endings. In the case of SOP and to a lesser extent ZRS and ANO, party support followed an almost pure parabola (y=100-(x-10)^2), but in one other party—Smer—we saw the beginnings of decline followed by a subsequent rise. Of course Smer ended up out of government after its first election and became a reservoir for disaffected voters and those who left HZDS. SaS, by contrast, is saddled with governing responsibilities, few resources for party-building activities, and three deputies (until recently four) who were never part of the party to begin with and who have one foot out the door. SaS has so far at least stayed out of the kind of internal trouble that will likely kill Veci Verejne in the Czech Republic (more on this in the next post) but its preference trajectory is not all that different from VV. The matter is serious: as the graph shows, only one major new party has survived infancy and SaS does not possess the same favorable characteristics or the same preference trajectory.

SaS has seen a slight post-election decline after a rapid pre-election rise. We have seen this pattern before in many similar parties—ZRS, SOP, ANO and Smer—but we have also seen two different endings. In the case of SOP and to a lesser extent ZRS and ANO, party support followed an almost pure parabola (y=100-(x-10)^2), but in one other party—Smer—we saw the beginnings of decline followed by a subsequent rise. Of course Smer ended up out of government after its first election and became a reservoir for disaffected voters and those who left HZDS. SaS, by contrast, is saddled with governing responsibilities, few resources for party-building activities, and three deputies (until recently four) who were never part of the party to begin with and who have one foot out the door. SaS has so far at least stayed out of the kind of internal trouble that will likely kill Veci Verejne in the Czech Republic (more on this in the next post) but its preference trajectory is not all that different from VV. The matter is serious: as the graph shows, only one major new party has survived infancy and SaS does not possess the same favorable characteristics or the same preference trajectory.

The Small Perennials

There are only four parties in Slovakia that have managed a consistent level of preference and parliamentary representation, and even these are not exactly the sort of “stable, long term” party that is often extolled in the political science literature. Two of these parties are relatively small but otherwise quite different: the Slovak National Party and the Christian Democratic movement:

About KDH there is little to say. The party continues to demonstrate a noteworthy stability. It ebbs and flows, largely in response to the attractiveness of adjacent parties such as SDKU and the success of its own political initiatives, but it stays between 8% and 10% in almost every poll. While there is no clear proof of the proposition, KDH lends weight to inverse relationship between party stability and party leadership: whereas other leader-centered parties have fluctuated wildly in the past (based in part on the decisions and reputation of the leader), KDH has changed its leader 3 times in regular cycles while remaining relatively consistent in terms of its policies, its electorate and, perhaps as a result, the size of that electorate.

About KDH there is little to say. The party continues to demonstrate a noteworthy stability. It ebbs and flows, largely in response to the attractiveness of adjacent parties such as SDKU and the success of its own political initiatives, but it stays between 8% and 10% in almost every poll. While there is no clear proof of the proposition, KDH lends weight to inverse relationship between party stability and party leadership: whereas other leader-centered parties have fluctuated wildly in the past (based in part on the decisions and reputation of the leader), KDH has changed its leader 3 times in regular cycles while remaining relatively consistent in terms of its policies, its electorate and, perhaps as a result, the size of that electorate.

About SNS there is more room for speculation. SNS has, at least in some polls, halted the sharp decline in support that began in the 2008s, but the party’s support remains extremely close to the 5% threshold despite the continuation of sharp action by Hungary’s government (of the sort that conventional wisdom has linked to increases in SNS support). It is unlikely that former SNS president Anna Belousovova’s proposed new party will draw away too many of the faithful but SNS does not need to lose much to eliminate its parliamnentary representation. The losses to Smer and the LS-NS in 2010 brought it within 2000 votes of the threshold. A few additional losses to Belousovova could eliminate it entirely from parliament (as happened in 2002).

About SNS there is more room for speculation. SNS has, at least in some polls, halted the sharp decline in support that began in the 2008s, but the party’s support remains extremely close to the 5% threshold despite the continuation of sharp action by Hungary’s government (of the sort that conventional wisdom has linked to increases in SNS support). It is unlikely that former SNS president Anna Belousovova’s proposed new party will draw away too many of the faithful but SNS does not need to lose much to eliminate its parliamnentary representation. The losses to Smer and the LS-NS in 2010 brought it within 2000 votes of the threshold. A few additional losses to Belousovova could eliminate it entirely from parliament (as happened in 2002).

The Large Perennials

The two larger parties—Smer and SDKU—have engaged in sustained battle for the last 9 years, each vying for leadership, though the nature of “leadership” is different: Smer’s outsized lead over all parties, foe and friend alike, has allowed it to dominate its side of the political spectrum since 2004 or so, whereas SDKU must operate as a first among equals among its potential partners. Ironically, the election of 2010 left Smer with a larger parliamentary delegation but pushed it out of government while allowing an electorally weaker SDKU lead the next government.

SDKU benefited from its “victory” with an increase in the share of its preferences to the highest sustained levels in the party’s history. That this high-level should hover around 16% is an indication of the party’s lack of overall strength, but at least gives it a 2:1 lead over its next nearest coalition partner. It is hard for me to judge why SDKU should be relatively successful while it leads a government that has been notable for its internal weaknesses and difficulty in achieving relatively clear-cut goals (such as the election of a general prosecutor), but it while it has had its share of minor scandal, it has at least stayed clear of deep level corruption (or at least the publicization thereof) and has addressed many of the more difficult allegations head on.

SDKU benefited from its “victory” with an increase in the share of its preferences to the highest sustained levels in the party’s history. That this high-level should hover around 16% is an indication of the party’s lack of overall strength, but at least gives it a 2:1 lead over its next nearest coalition partner. It is hard for me to judge why SDKU should be relatively successful while it leads a government that has been notable for its internal weaknesses and difficulty in achieving relatively clear-cut goals (such as the election of a general prosecutor), but it while it has had its share of minor scandal, it has at least stayed clear of deep level corruption (or at least the publicization thereof) and has addressed many of the more difficult allegations head on.

Smer has also risen in the last 10 months and by a relatively significant amount. After receiving nearly 35% percent in the 2010 elections, it has increased its preferences until they nearly approach the party’s previous highs in early 2007 and early 2009. The growth is impressive and Smer has done everything it could to remain actively part of the news cycle, with almost daily press releases, allegations and proposals and a party leader who is more accessible to (and less outraged by) the press. But there are several reasons to view’s Smer’s resurgence with a bit of skepticism.

Smer has also risen in the last 10 months and by a relatively significant amount. After receiving nearly 35% percent in the 2010 elections, it has increased its preferences until they nearly approach the party’s previous highs in early 2007 and early 2009. The growth is impressive and Smer has done everything it could to remain actively part of the news cycle, with almost daily press releases, allegations and proposals and a party leader who is more accessible to (and less outraged by) the press. But there are several reasons to view’s Smer’s resurgence with a bit of skepticism.

The first of these is that the party consistently does worse than its polling. For several years this exhibited itself as a surprise in the elections. Since 2006 it has been more a case of voters shifting their opinion (or their decision to vote at all) during the election campaign, so that Smer has not necessarily done worse than its election week polling but it has done considerably worse than its polling in 3-6 months before the election. Of course in each case this could be the result of circumstantial changes (perception of a worsening economy likely had some effect on Smer support in 2010) but the pattern is fairly consistent and suggests a softness in the support for Smer that may remain: the party tends to attract the disgruntled but does not necessarily keep them on election day.

Even if Smer does keep all of its preferences, there is a second reason for caution about the share of Smer supporters. As in the two previous elections, the big question for Smer is not its own success but that of its partners. The collapse of HZDS and near collapse of SNS left Smer without any options for a governing coalition in 2010 even though it won by far the largest share of the vote. The situation has, if anything, gotten worse.

In March of 2009, the ruling coalition of Smer-SNS-HZDS had 61.9% of the vote and could expect to win 110 of the 150 seats in parliament. Of those, Smer alone had 45.2% of the vote and 73 seats, while its partners together had 16.7% of the vote and could expect 27 seats. Exactly two years later, after a decline in 2010 and recovery through 2011, Smer again has 44% and which would give it 73 seats in parliament. But its former coalition partners can now expect only 9.2% of the vote and only 10 seats. And those 10 seats hang by a less-than-1% margin. The graph below offers a clear picture of how the “national” and “extreme left” portion—the parties at the bottom—of the political spectrum have weakened over time. Smer has likely absorbed much of the decline, but the segment has diminished even when Smer is added into the totals. Its absorption of the nationally oriented segment of the electorate has come at some cost, apparently (or if not, then it has lost other voters for other reasons). Smer is thus bigger but not so big that it can govern without others. Smer still needs partners if it hopes to gain a parliamentary majority, but it has not yet figured out how to keep old friends (or at least keep them alive) or cultivate new ones.

————————-

One final note that will prove to be of great importance to this blog: I owe a debt for the collection and analysis of public opinion data over the last six months to Jozef Janovský, student of political science and international relations in the Faculty of Social Studies at Masaryk University in Brno. Over the coming months I hope to work woth Jozef and several other colleagues to broaden the kinds of resources that are available in this blog. I’m thankful to Jozef for reaching out and offering his extremely capable assistance and I look forward to our collaboration.

One final note that will prove to be of great importance to this blog: I owe a debt for the collection and analysis of public opinion data over the last six months to Jozef Janovský, student of political science and international relations in the Faculty of Social Studies at Masaryk University in Brno. Over the coming months I hope to work woth Jozef and several other colleagues to broaden the kinds of resources that are available in this blog. I’m thankful to Jozef for reaching out and offering his extremely capable assistance and I look forward to our collaboration.

Good article, but you have one mistake. “(no party has returned to parliament without a coalition once it has fallen short of the threshold, and KSS is the only example of a party that has entered parliament after previously campaigning and falling short.”

The other example is SNS which did not make it to the parliament in 2002 after Slota left it and created the True SNS.

Thank you for sharing the political parties overview:)

Daniel Sukup, Assistant Editor, http://www.BratislavaGuide.com

You are absolutely right. Thanks for this.